Battle of Canton (1857)

| Battle of Canton | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Opium War | |||||||

British and French bombardment, 28 December | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5,679[1] Several warships[2][page needed] Artillery batteries on Dutch Folly and nearby islands[2][page needed] | 30,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

15 killed 113 wounded[3] | 200–650 casualties (est.)[4][2][page needed] | ||||||

The Battle of Canton (Chinese: 廣州城戰役) was fought by British and French forces against Qing China on 28–31 December 1857 during the Second Opium War. The British High Commissioner, Lord Elgin, was keen to take the city of Canton (Guangzhou) as a demonstration of power and to capture Chinese official Ye Mingchen, who had resisted British attempts to implement the 1842 Treaty of Nanking. Elgin ordered an Anglo-French force to take the town and an assault began on 28 December. Allied forces took control of the city walls on 29 December but delayed entry into the city itself until 5 January. They subsequently captured Ye and some reports state they burnt down much of the town. The ease with which the allies won the battle was one of the reasons for the signing of the Treaty of Tientsin in 1858.

Prelude

[edit]The British had been permitted access to Canton (Guangzhou) at the end of the First Opium War under the terms of the 1842 Treaty of Nanking, but were being illegally barred from entry by its viceroy Ye Mingchen.[2][page needed] In 1856, there had been a series of attacks on the Thirteen Factories and its residences, culminating with their complete destruction by fire. This and the seizure of a foreign ship led the British to assemble a force to demand reparations.[5][page needed] Although the British Royal Navy had destroyed the Chinese junks during the summer, an attack on Canton was delayed by the Indian Mutiny.[6] On 12 December 1857 the British High Commissioner to China, Lord Elgin, wrote to Ye demanding that he implement in full the trade and access agreements made in the 1842 Treaty of Nanking that ended the First Opium War and that he pay reparations for British losses in the war so far. Elgin promised that if Ye agreed within ten days then British and French forces would cease offensive actions, though they would retain possession of key forts until a new peace treaty was signed.[2][page needed]

Ye Mingchen was told he had 48 hours to comply.[7][page needed] Ye's reply was that Britain had effectively abandoned its rights with regards to Canton through eight years of inactivity, that the cause of the war (the loss of the merchant ship Arrow) had been of the British making and that he could not sign a new peace treaty because the 1842 treaty had been decreed by the emperor to last for 10,000 years. Elgin boarded HMS Furious on 17 December and sailed upriver towards Canton. On 21 December, Elgin ordered British Admiral Michael Seymour, French Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly and British General Charles van Straubenzee to take Canton and handed over full operational control.[2][page needed]

British and French troops reconnoitred the city on 22 December.[8] The allied force amounted to 800 men from the Indian Royal Sappers and Miners and the British 59th (2nd Nottinghamshire) Regiment of Foot, 2,100 Royal Marines, a 1,829-man naval brigade drawn from the crews of British ships and a 950-man force from the French Navy arrayed against a Chinese garrison of 30,000 men.[2][page needed][6][8] However the allies could count on the supporting fire of Anglo-French naval vessels and artillery batteries on Dutch Folly and other nearby islands.[2][page needed]

Battle

[edit]

The main battle began with a naval bombardment throughout the day and night of 28 December. The next day troops landed, taking a small fort, by Kupar Creek to the south-east of the city.[8][9]: 503 The Chinese had thought that the attacking forces would try to capture Magazine Hill before they moved on the city walls, but on the morning on 29 December after a naval bombardment ending at 9am French troops climbed the city walls with little resistance. They had arrived at the wall half an hour early and so faced fire from their own guns.[2][page needed] The British also broke into the city through the East gate.[9]: 504

Over 4,700 British and Indian troops and 950 French troops scaled the city walls[6] The walls were occupied for a week, then the troops moved into the streets of the city that contained over 1,000,000 people, on the morning of 5 January.[8] Sources put Chinese casualties at 450 soldiers and 200 civilians.[2][page needed][10] British losses amounted to 10 sailors and three soldiers killed and 46 sailors, 19 marines and 18 soldiers wounded.[3] French losses were two sailors killed and 30 wounded.[3] (Some Chinese sources estimate tens of thousands of Chinese were killed or captured and nearly 30,000 homes were burned down, although in view of the very light casualties of the attackers, the number of killed or captured is most unlikely) The delay in entering the city might have been because of the fires started by the bombardment.[citation needed]

Aftermath

[edit]

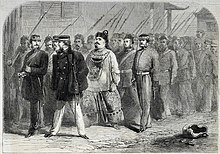

Commissioner Ye Mingchen was captured and taken to Calcutta where he starved himself to death a year later.[2] Once the British and French had occupied the city they established a joint governing commission.[11] Partly due to the battle and subsequent occupation – the Chinese wanted to avoid a repeat of the battle in Beijing – the Treaty of Tientsin was signed on 26 June 1858, ending the Second Opium War.[10][11]

During the Allied occupation, the local populace retained a massive degree of hostility to all foreigners in Canton, to the point where the Anglo-French forces contemplated then abandoned plans to conduct a second bombardment of the city. In the spring of 1858, a full-fledged resistance movement had formed against the occupation, and assassination attempts against Allied sentries and Western civilians were commonplace; in response, the French occupational forces carried out reprisals in quarters of the city and local villages where such attacks had occurred. In July, a Chinese force unsuccessfully attempted to recapture Canton by storming the city. By September, attacks on foreigners in Canton had mostly subsided.[12]

The residencies, which had been burnt down in 1856, were not rebuilt, they were moved to a manmade island further up the river named Shamian. Shamian Island was entirely cut off from the local population, accessible only over two guarded bridges.[13][page needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b The London Gazette: p. 1021. 26 February 1858. Issue 22104.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Elleman, Bruce A. (2008). Naval coalition warfare: from the Napoleonic War to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77082-8.

- ^ a b c The London Gazette: p. 1026. 26 February 1858. Issue 22104.

- ^ Cooke, George Wingrove (1858). China: Being "The Times" Special Correspondence from China in the Years 1857–58. p. 357.

- ^ Davies, Nicholas Belfield. The Treaty Ports of China and Japan: A Complete Guide to the Open Ports. ISBN 9781108045902.

- ^ a b c Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at war, 1815–1914: an encyclopedia of British military history. ABC-CLIO. p. 100. ISBN 1-57607-925-2.

- ^ Wong, J. Y. Deadly Dreams: Opium and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. ISBN 9780521526197.

- ^ a b c d Carter, Thomas (1861). "Capture of Canton". Medals of the British Army, and how they were won. Vol. 3. Groombridge and sons. p. 186.

- ^ a b Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ^ a b Santella, Thomas M. (2007). Opium. Infobase Publishing. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-7910-8547-9.

- ^ a b Harris, David (1999). Of battle and beauty: Felice Beato's photographs of China. University of California Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-89951-100-7.

- ^ "The Anglo-French occupation of Canton, 1858–1861" (PDF). Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch.

- ^ "Rise and fall of the Canton trade system" (PDF). ocw.mit.edu.