Aparan

Aparan

Ապարան | |

|---|---|

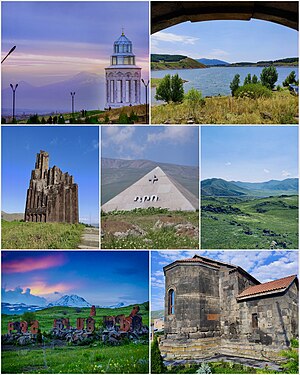

From top left: Holy Angels Church with Mount Aragats Aparan reservoir • Battle of Abaran memorial Mausoleum of Dro • Natural landscape of Aparan Armenian alphabet park • Kasagh Basilica | |

| Coordinates: 40°35′20.81″N 44°21′25.97″E / 40.5891139°N 44.3572139°E | |

| Country | Armenia |

| Province | Aragatsotn |

| Municipality | Aparan |

| First mentioned | 2nd century |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.5 km2 (1.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,880 m (6,170 ft) |

| Population (2022 census) | |

• Total | 5,803[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (GMT) |

| Website | Official website |

| Sources: Population[2] | |

Aparan (Armenian: Ապարան [ɑpɑˈɾɑn], colloquially [ɑbɑˈɾɑn]) is a town in the Aparan Municipality of the Aragatsotn Province of Armenia, about 50 kilometers northwest of the capital Yerevan. As of the 2011 census, the population of the town was 6,451. As per the 2016 official estimate, Aparan had a population of around 5,300. As of the 2022 census, the population of the town was 5,803.[1]

Etymology

[edit]It is commonly believed that the name of Aparan is derived from the Armenian word Aparank, meaning a royal palace. However, throughout history, the town has been known by different names including Kasagh, Paraznavert, Abaran and Abaran Verin. Later, it was known as Bash Aparan (Բաշ Ապարան) until 1935, when the name was finally changed to Aparan.[3]

History

[edit]Early history and Middle Ages

[edit]

In antiquity, the region of Aparan was known as Nig or Nigatun.[5] The first reference to the town of Aparan was made by Ptolemy during the 2nd century. Ptolemy referred to the settlement as Casala; the Hellenized version of the Armenian name of Kasagh. It was the centre of the Nig canton of the Ayrarat province of ancient Armenia. Kasagh was under the administration of the Gntunik Armenian noble family, under the rule of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia. The Gntunik princes founded the Basilica of Kasagh by the end of the 4th and beginning of the 5th centuries.[3] It was originally within the grounds of the Arsacid (Arshakuni) palace of the kings of Armenia, located in the town.[6][7]

Between the 9th and 11th centuries, Aparan was part of the Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia with the Gntuni princes being registered as vassal princes of the Bagratids.[8] Starting from the 10th century, the settlement of Kasagh became known as Aparan. The new name was originated from the village of Aparank located in the Moxoene province of the Kingdom of Armenia, when some remains from the ancient Armenian monastery of Surp Khach of Aparan were transferred to the town of Kasagh.

From the mid 10th to the late 12th centuries, Aparan came under the control of various Muslim dynasties, namely the Kurdish Shaddadids and the Turkic Delimks (originating from modern-day Iran). During this period, Aparan was locally administered by the Armenian Pahlavouni princes.[8] After the fall of Ani to the Byzantines in 1045, the Seljuks occupied most parts of the Armenian Highland by 1064.[8] However, in the late 12th century, Aparan again came under Armenian rule with the establishment of Zakarid Armenia. The Zakarian rulers granted governance of the area to the Vachutian noble family who invested in multiple architectural works along the Kasagh valley. They ruled until the 14thth century, Armenia became part of the Ilkhanate of the Mongol Empire.[8]

By the last quarter of the 14th century, the Aq Qoyunlu Sunni Oghuz Turkic tribe took over Armenia, including Aparan, before being invaded by Timur in 1400.[9] In 1410, Armenia fell under the control of the Kara Koyunlu Shia Oghuz Turkic tribe.

Early modern period

[edit]Between 1502 and 1828, Armenia became part of the Persian state under the rule of Safaavid, Afsharid and Qajar dynasties, with short periods of Ottoman rule between 1578 and 1603 and later between 1722 and 1736.[10]

In the 16th century, the Latin diocese of Nakhchivan's actual see (not the title) was moved to more central Aparan, closer to the actual Catholic communities. Around 1620, Pope Gregory XV instigated the founding of a Fratres Unitores (exclusive Armenian Dominican order branch) seminary in Aparan. The see was elevated on 21 February 1633 as non-Metropolitan Archdiocese of Nakhchivan, but diocesan activity seemingly effectively halted later that century. It would be suppressed in 1847, apparently vacant since 1765, as its faithful had fled the country during the devastating wars between the Ottomans and Safavids.[11]

The Armenian historian Zacharia of Kanaker, used the name Kasagh to refer to Aparan during the 17th century.[12] Starting from the 18th century, Aparan became known as Bash-Aparan in Persian and Turkic documents. Bash-Aparan was the centre of the Aparan Mahal (district) of the Erivan Khanate of Persia. During that time, it had no settled population of Armenians or Muslims due to it being located on the northern frontier in a frequent war zone.[13] The mahal was claimed by Turkic nomads of the Büyuk-chobankara tribe, who used it as land for their pastures and temporary settlements.[14]

On July 8, 1826, the town of Bash-Aparan was captured from the Khanate (under Qajar suzerainty) by the Russian army.[15] In 1828, after the Russo-Persian War, Aparan was among the lands that were handed over to the Russian Empire as a result of the Treaty of Turkmenchay signed on 21 February 1828.[16]

Modern history

[edit]

During the years of the Armenian genocide, many Armenian refuge families arrived in Bash-Aparan from the Western Armenian cities of Van, Mush, Alashkert and Karin between 1914 and 1918. Many other families had also arrived from the Eastern Armenian town of Khoy.[3]

The town was the site of the Battle of Abaran against the Turkish army on May 21, 1918, during the Caucasus Campaign of World War I, when the Turkish invasion of the newly independent Republic of Armenia was turned around. During the brief period of independence, Bash-Aparan became a gavar (administrative district) of Armenia.[3]

Under the Soviet rule, the Bash-Aparan raion was founded in 1930. In 1935, the name was officially changed to Aparan. In 1963, Aparan was granted with the status of an urban-type settlement.

An impressive monument to the Battle of Abaran was erected in 1978 just north of the town, designed by architect Rafael Israelyan.[3]

Following the independence of Armenia from the Soviet Union, Aparan was given the status of a town within the Aragatsotn Province, as per the administrative reforms of 1995.

Geography

[edit]

Historically, Aparan is located in Nig canton of Ayrarat Province of the Kingdom of Armenia Mayor.

Modern-day Aparan is located at the eastern slopes of Mount Aragats and the northern slopes of Mount Ara, on the shores of Kasagh River, with an elevation of 1880 metres above sea level. The town is located at a road distance of 42 km north of Yerevan and 32 km north of the provincial capital Ashtarak, on the main north–south road of Armenia.

Climate

[edit]Aparan has an Alpine climate in general with the influence of cold semi-arid climate. The town is characterized with snowy winters and mild humid summers. The average temperature is around -8 °C in winter and 17 °C in summer. The annual precipitation amount is around 700 millimeters.

| Climate data for Aparan (1991–2020, extremes 1981-2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.4 (48.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

17.8 (64.0) |

24.1 (75.4) |

25 (77) |

29.5 (85.1) |

33.4 (92.1) |

35 (95) |

30.2 (86.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

35.0 (95.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −7.8 (18.0) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

5.1 (41.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.7 (63.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

7.4 (45.3) |

0.4 (32.7) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.9 (−20.0) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

−30.1 (−22.2) |

−17 (1) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

1.9 (35.4) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

−24.6 (−12.3) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−30.6 (−23.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.9 (1.69) |

49.2 (1.94) |

60.5 (2.38) |

84.0 (3.31) |

87.6 (3.45) |

75.3 (2.96) |

81.9 (3.22) |

64.7 (2.55) |

37.8 (1.49) |

43.6 (1.72) |

39.1 (1.54) |

49.0 (1.93) |

715.6 (28.18) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.3 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 11.1 | 13.4 | 10.9 | 9.7 | 7.1 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.8 | 101.3 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71.4 | 69.5 | 66.3 | 65.2 | 66.1 | 64 | 64.1 | 60.8 | 61.4 | 67.6 | 69.3 | 71.9 | 66.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 103.6 | 116.6 | 159.6 | 166 | 214.7 | 266 | 300.8 | 286.4 | 241.6 | 178.3 | 136.1 | 99.4 | 2,268.9 |

| Source: NOAA[17](Extremes 1981-2010)[18] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1831 | 386 | — | ||

| 1873 | 1,353 | +3.03% | ||

| 1914 | 2,337 | +1.34% | ||

| 1931 | 2,666 | +0.78% | ||

| 1959 | 2,662 | −0.01% | ||

| 1979 | 5,990 | +4.14% | ||

| 2001 | 6,614 | +0.45% | ||

| 2011 | 6,451 | −0.25% | ||

| 2022 | 5,803 | −0.96% | ||

| ||||

| Source: [19] | ||||

The vast majority of the population belong to the Armenian Apostolic Church. The regulating body of the church is the Diocese of Aragatsotn with the Saint Mesrop Mashtots Cathedral in Oshakan. The churches of the Holy Cross and the Holy Mother of God, dating back to the 5th and 19th centuries respectively, are still operating up to the day.[19]

Culture

[edit]

Aparan has a palace of culture, a public library, a music school, and a school of art run by the municipality.

There are many places of cultural interest in the town :

- Kasagh Basilica of the Holy Cross, built during the 4th century, one of the oldest surviving churches in the Armenian highland.[20] The church is undated and was partly restored in 1877.[20]

- Monument to the Battle of Abaran erected in 1978.

- Mausoleum of General Drastamat Kanayan near the battle memorial, reburied in Aparan on 28 May 2000.

- Aparan Alphabet park and the statue of the 12th-century Armenian scholar Mkhitar Gosh.

- The 33-meters high Holy Cross of Aparan and the Holy Trinity Altar of Hope consecrated in October 2012. The cross is a metallic structure consisted of a number of small metallic crosses, referring to the number of years since Armenia adopted Christianity in 301. Thus, every year in October, a cross is being added to the monumental structure.[21]

Transportation

[edit]Aparan is located on the M-3 Motorway that connects the Armenian capital Yerevan with the Georgian capital Tbilisi, passing through Aparan on the way to Lori Province. A network of regional roads connects the town with the surrounding villages, as well as the provinces of Shirak and Armavir.

Economy

[edit]

Aparan used to be a major centre of carpet and textile production during the Soviet years. However, with collapse of the USSR the economy had drastically declined.

Currently, Aparan is home to the Nig factory for electrical products founded in 1964, the Aparan Cheese Factory founded in 1982 (privatized in 1995), and the Aparan Group for bottled water, soft drinks and dairy products, founded in 2006, and the Gntunik plant for bakery and dairy products.

Many restaurants of Aparan offer local and traditional cuisine, and tourist are accommodated in the Kasaghi Amrots hotel.[citation needed]

Education

[edit]As of 2017, Aparan is home to 2 primary schools, as well as the Aparan physics and mathematics high school. There are also 2 pre-school kindergartens operating in the town.

The Aparan physics and mathematics high school was founded in 2009 on the basis of Yeghishe Varzhapet's school opened in 1903. Currently, housing around 180 students, the school has specialized classes in humanities, natural science and mathematics. The school is equipped with up-to-date laboratories for physics, chemistry, and biology, along with 2 computer rooms.[22]

Sport

[edit]FC Nig Aparan represented the town in the domestic football competitions after the independence of Armenia. However, like many other Armenian clubs, it was dissolved in 1999 due to financial difficulties. The town has a sports school with a football training field.

Aparan used to be a major centre for winter sports. A ski resort with ski lifts used to operate near the town during the Soviet days. It is envisaged to rebuild the resort in the near future.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Main Results of RA Census 2022, trilingual / Armenian Statistical Service of Republic of Armenia". www.armstat.am. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ 2011 Armenia census, Aragatsotn Province

- ^ a b c d e Hakobyan, Tadevos Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, Stepan T.; Barseghyan, Hovhannes Kh. (1986). "Ապարան [Aparan]". Հայաստանի և հարակից շրջանների տեղանունների բառարան [Dictionary of Toponyms of Armenia and Adjacent Territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 1. Yerevan State University Press. p. 306. OCLC 247335945.

- ^ Trever, Kamilla (1953). Очерки по истории культуры древней Армении [Essays on the cultural history of ancient Armenia: (II century BC - IV century AD)] (in Russian). Moscow: Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. pp. 272–273. OCLC 6738397.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert (1987). Ayrarat. Vol. III. Encyclopædia Iranica. pp. 150–151.

Nig or Nigatun (land of Nig, Greek Nigē) corresponds to the modern raion of Abaran in the valley of the Kʿasał river north of Aragacotn.

- ^ Arakelian, Babken N.; Yeremian, Suren T.; Arevshatian, Sen S.; Bartikian, Hrach M.; Danielian, Eduard L.; Ter-Ghevondian, Aram N., eds. (1984). Հայ ժողովրդի պատմություն հատոր II. Հայաստանը վաղ ֆեոդալիզմի ժամանակաշրջանում [History of the Armenian People Volume II: Armenia in the Early Age of Feudalism] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing. p. 566.

- ^ Shakhkyan, G. (1986). "Քասաղի բազիլիկ [Kasagh basilica]". Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia Volume 12 (in Armenian). p. 419.

- ^ a b c d Franklin, Kate (2021). "Making and Remaking the World of the Kasakh Valley". Everyday Cosmopolitanisms: Living the Silk Road in Medieval Armenia (1 ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. pp. 66–68. ISBN 978-0-520-38093-6. JSTOR j.ctv2rb75kr.9.

- ^ Bedrosian, Robert (1979). "Armenia and the Turco-Mongol Invasions". The Armenian Lords in the 13th-14th Centuries. Columbia University PHD Dissertation. pp. 63–155. OCLC 35087735. Archived from the original on September 4, 2016.

- ^ Herzig, Edmund (2000). "Armenia: History". Eastern Europe, Russia and Central Asia 2003. Taylor & Francis. p. 76-80. ISBN 9781857431377.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2023). "In the Wake of International Great-Power Politics". History of the Caucasus: In the Shadow of Great Powers. Vol. 2. United Kingdom: I.B. Tauris. p. 47. ISBN 9780755636303.

- ^ Brosset, Marie-Félicité (1874). "Notice sur le diacre arménien Zakaria Ghabonts auteur des Mémoires historiques sur les Sofis, XVe - XVIIe" [Notice on the Armenian deacon Zakaria Ghabonts author of the Historical Memoirs on the Sofis, 15th-17th centuries]. Bulletin de l'Académie impériale des sciences de Saint-Pétersbourg (in French). St. Petersburg: Russian Academy of Sciences: 321–322. ISSN 1029-998X.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. (1992). The Khanate of Erevan Under Qajar Rule: 1795–1828. Mazda Publishers. pp. 34, 37. ISBN 978-0939214181.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. (1980). The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826–1832. The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies. p. 7.

- ^ Behrooz, Maziar (2023). Iran at War: Interactions with the Modern World and the Struggle with Imperial Russia. I.B. Tauris. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-7556-3737-9.

- ^ Pourjavady, Reza (2023). "Russo-Iranian wars 1804-13 and 1826-8". In Thomas, David; Chesworth, John A. (eds.). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History Volume 20. Iran, Afghanistan and the Caucasus (1800-1914). Vol. 20. Germany: BRILL. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9789004526907.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Aparan-37699" (CSV). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010". National Centers for Environmental Information. Archived from the original (XLSX) on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- ^ a b Հայաստանի Հանրապետության բնակավայրերի բառարան [Republic of Armenia settlements dictionary] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Cadastre Committee of the Republic of Armenia. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2018.

- ^ a b Thierry, Jean-Michel (1989). Armenian Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 545. ISBN 0-8109-0625-2.

- ^ Holy Cross of Aparan and the Holy Trinity Altar of Hope consecrated in Aparan

- ^ "Aparan physics and mathematics high school". Archived from the original on 2017-11-02. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ^ About the town of Aparan (Armenian)