Barda, Azerbaijan

Barda

Bərdə | |

|---|---|

City & Municipality | |

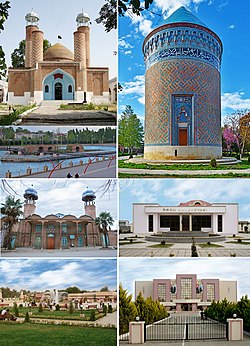

Landmarks of Barda, from top left: Imamzadeh Mausoleum • Barda Mausoleum Ancient bridge • State Art Gallery Barda Juma Mosque • Barda Sports Center Sabir Garden Park | |

| Coordinates: 40°22′28″N 47°07′36″E / 40.37444°N 47.12667°E | |

| Country | |

| Elevation | 76 m (249 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 41,277 |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Area code | +994 2020 |

Barda (Azerbaijani: Bərdə ) is a city and the capital of the Barda District in Azerbaijan, located south of Yevlax and on the left bank of the Tartar river. It served as the capital of Caucasian Albania by the end of the 5th-century.[2][3] Barda became the chief city of the Islamic province of Arran, the classical Caucasian Albania, remaining so until the tenth century.[4]

Etymology

[edit]The name of the town derives from (Arabic: برذعة, romanized: Bardhaʿa)[citation needed] which derives from Old Armenian Partaw (Պարտաւ).[5] The etymology of the name is uncertain. According to the Iranologist Anahit Perikhanian, the name is derived from Iranian *pari-tāva- 'rampart', from *pari- 'around' and *tā̆v- 'to throw; to heap up'.[6] According to the Russian-Dagestani historian Murtazali Gadjiev, however, the name means "Parthian/Arsacian" (cf. Parthian *Parθaυ; Middle Persian: Pahlav; Old Persian: Parθaυa-).[3] The name is attested in Georgian as Bardav[i] (ბარდავი).[7][8]

History

[edit]Ancient

[edit]According to The History of the Country of Albania, the Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) of Iran, Peroz I (r. 459–484) ordered his vassal the Caucasian Albanian king Vache II (r. 440–462) to have the city of Perozapat ("the city of Peroz" or "Prosperous Peroz") constructed. However, this is unlikely as the Kingdom of Caucasian Albania had been abolished by Peroz after a suppressing a revolt by Vache II in the mid-460s.[9] The city was seemingly founded by Peroz himself after the removal of the ruling family in Caucasian Albania. Due to its more secure location, it was made the new residence of the Iranian marzban (margrave).[10] Within Albania, it was located in the province of Utik.[11] The city was most likely renamed Partaw (cf. Parthian *Parθaυ) between 485–488 and became the new capital of Albania (thus replacing Kabalak) under Vachagan III (r. 485–510),[3][2] who was installed on the throne by Peroz's brother and successor Balash (r. 484–488).[12]

Regardless, the city did not serve as the residence of the Albanian kings, and was a symbol of foreign rule.[13] The city was fortified by shahanshah Kavad I (r. 488–496, 498/9–531) and renamed Perozkavad ("victorious Kavad").[12][3] Nevertheless, the city was still referred to as Partaw.[3] In 552, the city became the seat of the catholicos of the Church of Caucasian Albania.[3] Partaw served as the residence of the Sasanian prince Khosrow (the future Khosrow II) after his appointment to the governorship of Albania by his father Hormizd IV (r. 579–590) in 580.[14][15] Partaw was most likely captured before 652 by the Rashidun Caliphate.[4] It became known as Bardha‘a in Arabic.[16][17]

Medieval

[edit]

In ca. 789, it was made the second alternate capital (after Dvin) of the governor (ostikan) of the province of Arminiya.[18] Its governors strengthened the defenses of the city in order to counter the invasions of the Khazars attacking from the north.[4] In 768, the Catholicos of All Armenians, Sion I Bavonats'i, convoked an ecclesiastical council at Partav,[19] which adopted twenty-four canons addressing issues relating to the administration of the Armenian Church and marriage practices.[20] By the ninth to tenth centuries, Barda had largely lost its economic importance to the nearby town of Gandzak/Ganja; the seat of the Catholicos of the Church of Albania was also moved to Bardak (Berdakur), leaving Partav a mere bishopric.[20][21] According to the Muslim geographers Estakhri, Ibn Hawqal, and Al-Muqaddasi, the distinctive Caucasian Albanian language (which they called al-Raniya, or Arranian) persisted into early Islamic times, and was still spoken in Barda in the tenth century.[22] Ibn Hawkal noted that the people of Barda spoke Arranian,[23] while Estakhri says that Arranian was the language of the "country of Barda."[24]

During this time, the city boasted a Muslim Arab population, as well as a substantial Christian community.[4] Barda was even the seat of a Nestorian,(Christian) Bishopric in the 10th century. Referring to events in the late eleventh century, the twelfth-century Armenian historian Matthew of Edessa described Partav as an "Armenian city ["K'aghak'n Hayots'"], which is also called Paytakaran and located near the vast [Caspian] Sea."[25] Muslim geographers also described Barda as a flourishing town with a citadel, a mosque (the treasury of Arran was located here), a circuit wall and gates, and a Sunday bazaar that was called "Keraki," "Korakī" or "al-Kurki" (a name derived from Greek κυριακή [kyriaki], the Lord's Day and Sunday; the Armenian kiraki similarly derives from kyriaki).[4][26][27] In 914, the city was captured by the Rus, who occupied it for six months. In 943, it was attacked once more by the Rus and sacked.[28] This may have been a factor in the decline of Barḏa in the second half of the tenth century, along with the raids and oppression of the rulers of the neighboring regions, when the town lost ground to Beylaqan.[4]

Centuries of earthquakes and, finally, the Mongol invasions destroyed much of the town's landmarks, with the exception of the fourteenth-century tomb of Ahmad Zocheybana, built by architect Ahmad ibn Ayyub Nakhchivani. The mausoleum is a cylindrical brick tower, decorated with turquoise tiles. There is also the more recently built Imamzadeh Mosque, which has four minarets.[29]

Modern

[edit]Agriculture is the main activity in the area. The local economy is based on the production and processing of cotton, silk, poultry and dairy products. The cease-fire line, concluded at the end of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1994, is just a few kilometers west of Barda, near Terter.

On 27 October 2020, Armenian missiles struck the city which killed at least 21 civilians, including a 7 year old girl, and injured 70 others.[30][31] Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International verified the use of cluster munition by Armenia.[32][33]

Notable residents

[edit]- Mihranids of Caucasian Albania: Javanshir, Varaz-Tiridates I. etc.

- Arabic governors: Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Saj, etc.

- Paykar Khan Igirmi Durt. Qizilbash chieftain in the service of Safavid Persia in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His career flourished in the southeastern Caucasus, where he ran the governments of Barda and Kakheti on behalf of Shah Abbas I until being overthrown in a Georgian uprising in 1625.

References

[edit]- ^ World Gazetteer: Azerbaijan [dead link] – World-Gazetteer.com

- ^ a b Hoyland 2020, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d e f Gadjiev 2017, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d e f Bosworth 1988, pp. 779–780.

- ^ Pourshariati, Parvaneh. Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: the Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London: I.B. Tauris, 2008, p. 116, note 613.

- ^ (in Russian) Périkhanian, Anahit G. "Этимологические заметки" [Notes on Etymology]. Patma-Banasirakan Handes 1 (1982), 77-80.

- ^ Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 182, 239, 341. ISBN 978-1472425522.

- ^ Vacca, Alison (2017). Non-Muslim Provinces under Early Islam: Islamic Rule and Iranian Legitimacy in Armenia and Caucasian Albania. Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1316979853.

- ^ Gadjiev 2017, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Gadjiev 2017, p. 123.

- ^ Hoyland 2020, p. 44.

- ^ a b Chaumont 1985, pp. 806–810.

- ^ Hoyland 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Hoyland 2020, p. 211.

- ^ Howard-Johnston 2010.

- ^ Gadjiev 2017, p. 122.

- ^ Hoyland 2020, p. 39.

- ^ Ter-Ghevondyan, Aram N. (1976). The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Trans. Nina G. Garsoïan. Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. pp. 36–37.

- ^ Curtin, D. P. (December 2013). The Canons of the Synod of Partav. Dalcassian Publishing Company. ISBN 9781088093047.

- ^ a b (in Armenian) Ulubabyan, Bagrat. s.v. "Partav," Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia, vol. 9, p. 210.

- ^ Kirakos Gandzaketsi. History of the Armenians. Trans. Robert Bedrosian.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. "Arrān." Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ "Арабские источники о населенных пунктах и населении Кавказской Албании и сопредельных областей (Ибн Руста, ал-Мукаддасий, Мас'уди, Ибн Хаукаль)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-20. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ "СБОРНИК МАТЕРИАЛОВ". www.vostlit.info.

- ^ Matthew of Edessa (1993). Armenia and the Crusades: Tenth to Twelfth centuries: The Chronicle of Matthew of Edessa. Trans. Ara E. Dosturian. Lanham: University Press of America, p. 151.

- ^ Wheatley, Paul. The Places Where Men Pray Together: Cities in Islamic lands, Seventh through the Tenth Centuries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, p 159.

- ^ Estakhri states that there was a Sunday bazaar in Barda, known locally as "Koraki," which in the opinion of a scholar George Bournoutian derives directly from the Armenian, not the Greek, rendition of the word Sunday ("Kiraki"). On this basis, Bournoutian speculates that the city still had a significant Armenian element during the tenth century: see Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi, Two Chronicles on the History of Karabagh: Mirza Jamal Javanshir’s Tarikh-e Karabagh and Mirza Adigozal Beg’s Karabagh-name. Introduction and annotated translation by George A. Bournoutian. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2004, p. 40n2.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 256.

- ^ Turánszky, Ilona (1979). Azerbaijan, mosques, turrets, palaces. Corvina Kiadó. p. 56. ISBN 978-963-130321-6.

- ^ "Azerbaijan says 14 people killed by shelling in Barda: RIA". Reuters. 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Missile strike on Azeri town kills 21 civilians". BBC News. 2020-10-28. Retrieved 2020-10-28.

- ^ "Armenia/Azerbaijan: First confirmed use of cluster munitions by Armenia 'cruel and reckless'". Amnesty International. 29 October 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- ^ "Armenia: Cluster Munitions Kill Civilians in Azerbaijan". Human Rights Watch. 30 October 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Bosworth, C. E. (1988). "Barḏaʿa". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, Vol. III, Fasc. 7. New York. pp. 779–780.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chaumont, M. L. (1985). "Albania". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. I, Fasc. 8. pp. 806–810.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Gadjiev, Murtazali (2017). "Construction Activities of Kavād I in Caucasian Albania". Iran and the Caucasus. 21 (2). Brill: 121–131. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20170202.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2010). "Ḵosrow II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- Hoyland, Robert (2020). From Albania to Arrān: The East Caucasus between the Ancient and Islamic Worlds (ca. 330 BCE–1000 CE). Gorgias Press. pp. 1–405. ISBN 978-1463239886.

Further reading

[edit]- Barthold, Wilhelm (1987). "Bard̲h̲aʿa". In Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (ed.). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume II: Bābā Fighānī–Dwīn. Leiden: BRILL. p. 656. ISBN 90-04-08265-4.

- Dunlop, D.M. (1960). "Bard̲h̲aʿa". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume I: A–B. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 1040–1041. OCLC 495469456.

- Ter-Ghewondyan, Aram (1976) [1965]. The Arab Emirates in Bagratid Armenia. Translated by Garsoïan, Nina. Lisbon: Livraria Bertrand. OCLC 490638192.

- Ulubabyan, Bagrat (1981). Դրվագներ Հայոց արևելից կողմանց պատմության [Episodes from the History of the Eastern Regions of Armenia] Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences.