Balto (film)

| Balto | |

|---|---|

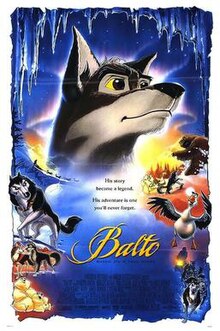

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Simon Wells |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Steve Hickner |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jan Richter-Friis (live action) |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 78 minutes |

| Countries | United States[1] United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $31 million[2] |

| Box office | $11 million[3] |

Balto is a 1995 live-action/animated adventure film directed by Simon Wells, produced by Amblin Entertainment and distributed by Universal Pictures.[4] It is loosely based on the true story of the eponymous dog who helped save children infected with diphtheria in the 1925 serum run to Nome. The film stars the voices of Kevin Bacon, Bridget Fonda, Phil Collins, and Bob Hoskins. Though primarily an animated film, it uses a live-action framing device that takes place in New York City's Central Park and features Miriam Margolyes as an older version of one of the children. This was the third and final film to be produced by Steven Spielberg's Amblimation animation studio, before the studio's closure in 1997.

Although the film was a financial disappointment due to being overshadowed by the success of Pixar's Toy Story, its subsequent sales on home video led to two direct-to-video sequels: Balto II: Wolf Quest (2002) and Balto III: Wings of Change (2005), though none of the original voice cast reprised their roles.

Plot

[edit]In New York City, an elderly woman and her granddaughter are walking through Central Park, looking for a memorial statue. As they seat themselves for a rest, the grandmother recounts a story about Nome, Alaska.

In 1925, a wolfdog named Balto lives on the outskirts of Nome with his adoptive father, a Russian snow goose named Boris, and two polar bears, Muk and Luk. Being a half-breed, Balto is ridiculed by dogs and humans alike. His only friends in town are a little girl named Rosy and her red husky Jenna whom Balto has a crush on. He is challenged by the town's favorite sled dog Steele, a fierce and arrogant Alaskan Malamute, and his teammates, Nikki, Kaltag and Star.

That night, Rosy and all the children fall ill with diphtheria. Severe winter weather conditions prevent medicine from being brought by air or sea from Anchorage, and the closest rail line ends in Nenana after authorization to transport the antitoxin by rail is given by the Governor of Alaska in Juneau. A dog race is held to determine the best-fit dogs for a sled dog team to get the medicine. Balto enters and wins, but gets disqualified after Steele exposes his wolf-dog heritage. The team departs that night with Steele in the lead and picks up the medicine successfully. On the way back, conditions deteriorate and the disoriented team ends up stranded at the base of a steep slope with the musher knocked unconscious.

When the word reaches Nome, Balto sets out in search of them with Boris, Muk, and Luk. On the way, they are attacked by a huge grizzly bear, but Jenna, who followed their tracks, intervenes. The bear pursues Balto out onto a frozen lake, where it falls through the ice and drowns. Muk and Luk save Balto from a similar fate. However, Jenna is injured and cannot continue on. Balto instructs Boris and the polar bears to take her back home while he continues on alone. Balto eventually finds the team, but Steele refuses his help and attacks him until he loses his balance and falls off a cliff. Balto takes charge of the team, but they lose their way again since Steele had sabotaged the trail. Balto falls while attempting to save the medicine from falling down a cliff.

Back in Nome, Jenna is explaining Balto's mission to the other dogs when Steele returns, lying the team, including Balto, is dead. However, Jenna sees through his deception and she assures Balto will return with the medicine. Using a trick Balto showed her earlier, Jenna places broken colored glass bottles on the outskirts of town and shines a lantern on them to simulate the lights of an aurora, hoping it will help guide Balto home. When Balto regains consciousness, he is ready to give up hope. When a large, white wolf appears and he notices the medicine crate still intact nearby, he realizes that his part-wolf heritage is a strength, not a weakness, and drags the medicine back up the cliff to the waiting team. Using his advanced senses, Balto is able to filter out the false markers Steele created.

After encountering further challenges though an ice bridge, an avalanche, and an ice cavern, and losing only one vial, Balto and the sled team finally return to Nome. A pity-playing Steele is abandoned by the other dogs who realized the truth about him. Reunited with Jenna and his friends, Balto earns respect from both the dogs and the humans. He visits a cured Rosy, who thanks him for saving her.

Back in the present day, the elderly woman and her granddaughter finally find the memorial commemorating Balto and she explains that the Iditarod trail covers the same path that Balto and his team took from Nenana to Nome. The woman, who is actually Rosy, repeats the same line "Thank you, Balto. I would have been lost without you". She walks off to join her granddaughter and her Siberian Husky Blaze. The Balto statue stands proudly in the sunlight.

Cast

[edit]

- Kevin Bacon as Balto, a brown-and-grey wolfdog; being a Siberian Husky-Arctic wolf hybrid. Jeffrey James Varab and Dick Zondag served as the supervising animators for Balto. Bacon is succeeded by Maurice LaMarche in the direct-to-video sequels, Balto II: Wolf Quest and Balto III: Wings of Change.

- Bob Hoskins as Boris Goosinov, a Russian snow goose and Balto's caretaker, mentor, adoptive father, and sidekick. Kristof Serrand served as the supervising animator for Boris. Hoskins is succeeded by his Who Framed Roger Rabbit co-star, Charles Fleischer in the sequels.

- Bridget Fonda as Jenna, a female copper-and-white Siberian Husky and Rosy's pet as well as Balto's love interest. Her facial design is based on actress Audrey Hepburn. Robert Stevenhagen served as the supervising animator for Jenna. Fonda is succeeded by Jodi Benson in the sequels.

- Jim Cummings as Steele, a fierce-looking black-and-white Alaskan Malamute who bullies Balto and also has a crush on Jenna. Sahin Ersöz served as the supervising animator for Steele. Brendan Fraser was originally cast to voice Steele before being replaced by Cummings.

- Phil Collins as Muk and Luk, a pair of polar bears, Boris' adoptive nephews, and Balto's adoptive cousins.[5] Nicolas Marlet designed and served as the supervising animator for Muk and Luk. Collins is succeeded by Kevin Schon in the sequels.

- Juliette Brewer as Rosy, a kind, excitable girl and Jenna's owner who was the only human in Nome who was kind to Balto before his epic journey. David Bowers served as the supervising animator for Rosy. Rosy makes a brief cameo in Balto III: Wings of Change.

- Miriam Margolyes as an old Rosy in the live-action sequences who narrates her story to her granddaughter at the beginning of the film.

- Jack Angel, Danny Mann and Robbie Rist as Nikki, Kaltag, and Star, respectively. The only three prominent members of Steele's team who later abandon him for Balto. Nikki is a reddish-brown Chow Chow, Kaltag is a honey-yellow Chinook, and Star is a mauve-and-cream Alaskan Klee Kai. William Salazar served as the supervising animator for the team. Nikki, Kaltag, and Star make brief cameos in Balto III: Wings of Change.

- Sandra Dickinson as Dixie, a female Pomeranian and one of Jenna's friends who adores Steele until his lies about Balto are exposed by Balto returning with the medicine needed to cure the children. Dickinson also voices Sylvie, a female Afghan Hound who is also Jenna's friend; and Rosy's mother. Patrick Mate designed and served as the supervising animator for Sylvie and Dixie, as well as all the principal human characters. Sylvie makes a brief cameo in Balto III: Wings of Change.

- Lola Bates-Campbell as Rosy's unnamed granddaughter who appears in the live-action sequences and is accompanied by her dog Blaze, a purebred Siberian Husky.

- William Roberts as Rosy's father

- Donald Sinden as Doc, an old St. Bernard. Doc makes a brief cameo in Balto III: Wings of Change.

- Garrick Hagon as a telegraph operator

- Bill Bailey as a butcher

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Screenwriter Elana Lesser first recalled being told the story of Balto by her grandfather as a child, and as an adult, felt that it would make an excellent animated film. She and screenwriter Cliff Ruby, pitched a screenplay to Amblin Entertainment in Universal City, California, and executives Douglas Wood and Bonne Radford subsequently relayed it to co-directors Phil Nibbelink and Simon Wells at Amblin's London-based animation studio, Amblimation. Although Steven Spielberg agreed that the story had potential, he was initially concerned that such a film would not be colorful enough. To reassure Spielberg, Wells showed him several color studies by production designer Hans Bacher, which showed that the film would not simply depict black and white dogs against a desolate scenery. Nibbelink and Wells had initially developed Balto together, before Nibbelink left to continue working on We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story (1993), and screenwriters Roger S. H. Schulman and David Steven Cohen, as well as several uncredited writers, did further development.[6]

Animation

[edit]Balto was officially put into production in March 1993, under the working title Snowballs.[7][8] To have a source for the dogs' character animation to be based on, the filmmakers set up special drawing classes, in which they brought in about seven Siberian Huskies and videotaped them walking around in the studio, while the animators studied their movements and anatomy.[9] During these classes, Kristof Serrand, who was assigned to supervise the animation on Boris, gave a lecture on the locomotion of dogs.[10] Former Disney animator Jeffrey J. Varab, who had trained under Eric Larson, was assigned to co-supervise the animation on Balto alongside Dick Zondag. At the behest of Wells, Varab also gave a dog anatomy lecture that focused on how Balto was to be drawn, drawing on his prior knowledge from his work on The Fox and the Hound (1981), as well as citing preliminary character sketches drawn by character designer Carlos Grangel and original model sheets of Tramp from Lady and the Tramp (1955).[11] Prior to his departure from the project, Nibbelink gave a lecture on how to apply spacing and weight to the dog animation, using the "bouncing ball" animation exercise, which he had learned from Frank Thomas while working as an animator at Disney alongside Varab.[12] In addition, Wells and several other crew members took special trips to Finland, where they studied dog sledding.[13]

The tight budget necessitated many difficult decisions; for instance, it was calculated that in most shots, the effects animators could not afford to include both footprints and shadows, and had to figure out what they could get away with omitting.[6] Another principal difficulty that the crew faced was that in order to achieve the snow colors and textures that Bacher's production design mandated, the background artists needed to use oil paint, instead of gouache or watercolor, like most other animated films. Because oil paint dries slower than gouache, the filmmakers had to schedule in extra days to allow each background to dry before they could shoot their scenes. According to producer Steve Hickner, an advantage that came from the longer drying time was that the artists could "work back into their art" days later, while the paint was still wet.[14]

Principal animation lasted from 1993 to 1994, with each animator completing five seconds of animation a week on average; Ken Keys, one of the animators on Steele, stated that he was "throwing away nine drawings to keep one."[15][16] Although the film was mainly hand-drawn animated, considerable computer animation was implemented into the film's more challenging visual elements; all of the falling snow was animated using an early CGI particle animation system.[6][13] All of the ink-and-paint work was also done using the 2D animation software program Toonz, making Balto the first animated film to use it. The program was still in its trial stages at the time, which necessitated an intense interaction with the developers.[17][18] Additional animation and clean-up work was done by the Danish studio A. Film Production.[19] Each shot was composited digitally and transferred to film through a "Solitaire" film recorder, before being spliced into the leica reel.[9]

Casting

[edit]Because the characters were designed before the voices were cast, the actors were given several inspirational character sketches to look at before each recording session, in order to get a sense of the characters they were portraying.[6] Initially, it was reported that Kevin Anderson had been cast as Balto.[20] Anderson had finished all of his voice-over work and the animation had been done around his performance, but late in production, Universal Pictures insisted on having a bigger name in the role, so he was replaced by Kevin Bacon, who had been filming Apollo 13 (1995) at Universal around the same time. Because of the completed animation, Bacon had to precisely match his timing to Balto's mouth movement.[21] According to Bacon, "It was very hard. I didn't like it. They would play his dialogue in the way that he had said it in my head right before I'd say my line."[22] Wells contradicted this, however, stating that though Bacon admitted to feeling constricted, he "did a terrific job and was really enthusiastic."[21]

Similarly, Brendan Fraser, who was filming Airheads (1994) at the time, was originally cast as Steele, because Wells had envisioned Steele as a school quarterback jock carried away by his sense of importance, and felt that Fraser fit that personality well. According to Wells, "I liked Brendan a great deal, and we did one recording session with him that was terrific." However, Spielberg wanted to feel a clearer sense of Steele's "inherent evil", so Fraser was replaced by Jim Cummings. Wells stated that Cummings "did a fantastic job, and totally made the character live, so I don't regret the choice."[6] Cummings was officially cast by January 1995, though Anderson was still listed at the time.[20] According to Cummings, several other on-camera actors were brought in to replace Fraser, before the role ultimately went to him. Spielberg, having been too busy with Schindler's List (1993) to attend Fraser's recording sessions, and not wanting to reject yet another unsatisfactory performance based on footage viewings, also insisted on directing Cummings personally, as well as completing his recording in one day.[23]

Jennifer Blanc also originally voiced Jenna, but she was also subsequently replaced by Bridget Fonda.[20] Fonda explained in an interview with Bobbie Wygant that she was offered the role of Jenna via phone call, and accepted after being shown a rough cut on tape, which showed some shots in finished form, some still in pencil test form, and some missing. When asked how hard it was to be doing voice-over work for animation for the first time, she explained, "It was odd, it was different. It was challenging. It was exhausting in that I had to be more active, and more outgoing vocally than usually. And syncing up to animated is very difficult. But, y'know, it was just so imaginative, and satisfying in a different way."[24]

Bob Hoskins, who had previously worked with Spielberg on Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988) and Hook (1991), voiced Boris, and Wells stated that his performance proved to be helpful in shaping the character, praising it as "a lot more emotional and effusive than we had originally conceived the character to be."[6] However, Wells also recalled a brief point at which, while struggling with Boris's accent, Hoskins vented his anger that he "used to have a career", before "playing a goose."[21] Phil Collins, despite having never done voice-over work before, actively expressed interest in the role of Muk and Luk, and even called Amblimation to ask for the role. Wells praised his voice for Muk as "just head and shoulders better than anything else we heard."[13] In his autobiography, Jack Angel stated that he, Danny Mann and Robbie Rist were flown to London to record their respective roles as Nikki, Kaltag and Star together, with his wife, Arlene Thornton, in tow. Angel added that even though they had no personal interaction with Spielberg, he flew Angel, Mann and Rist out again after they had finished recording their roles, because "somebody apparently didn't get it right the first time."[25]

Live-action segments

[edit]Screenwriter Frank Deese, who at the time was writing a script draft for Small Soldiers (1998) that was ultimately rejected, was hired by Radford to script the film's live-action prologue and epilogue segments in 1994, though he received no credit in the finished film.[26] The two segments were filmed on-location in Central Park later that year, over a period of one to two days. Closing down the area for filming proved to be a challenge, due to uncooperative locals. However, Wells greatly enjoyed working with Miriam Margolyes, and was impressed with how well she worked with Lola Bates-Campbell, who played Rosy's granddaughter.[21]

Music

[edit]The film score was composed by James Horner, who had previously scored An American Tail: Fievel Goes West (1991) and We're Back!. According to Wells, because Horner worked in California, and Amblimation was based in London, he "preferred to present his score as the orchestral finished product, and make alterations based on notes from that finished product."[6] Horner also collaborated with songwriting duo Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil to write an original song, "Reach for the Light", sung by Steve Winwood, which plays over the film's end credits. It was initially reported that the end credits would feature a song co-written by Neil Diamond and Carole Bayer-Sager, but this song never materialized.[20]

Historical differences

[edit]The film has many historical inaccuracies:

- The film portrays Balto (1919 – March 14, 1933) as a brown-and-gray wolfdog. In reality, Balto was a purebred Siberian Husky and was black and white in color.[27][28] Balto's colors changed to brown due to light exposure while on display in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.[29]

- Balto was never an outcast street dog as shown by the film, but was instead born in a kennel owned by the famous musher and breeder Leonhard Seppala, who raised and trained him until Balto was deemed fit for being a sled dog.

- In reality, the sled run to retrieve the medicine was actually a relay. Instead of being the leader of the first and only team, Balto was scheduled to be part of the penultimate team led by dog Fox. This team left by Seppala, while driven by Gunnar Kaasen. Although they were scheduled to hand off the serum to the final team, Kaasen decided to advance on. They eventually became the last team to carry the medicine to Nome.[30] The longest and most hazardous distance was traveled by the 18th and third-to-last team, which was led by Togo (October 17, 1913 – December 5, 1929).[31][32] However, considerable controversy surrounded Balto's use as a lead dog on Kaasen's team, including many mushers and others at the time doubting the claims that he truly led the team, based primarily on the dog's track record. It was believed that at most Balto was co-lead with Seppala's dog Fox.[33][32] No record exists of Seppala ever having used him as a leader in runs or races prior to 1925, and Seppala himself stated Balto "was never in a winning team",[34] and was a "scrub dog".[35]

- In the film, the reason why Dr. Curtis Welch orders the medicine to be sent to Nome is because his supply has completely run out. In reality, the reason was that his entire batch was past its expiration date and no longer had any effect.

- In the film, the medicine is shipped to Nenana from the Alaskan capital of Juneau, but in reality, it was shipped from Anchorage, 800 miles southeast of Nome.

- The medicine was transported in a 300,000 unit cylinder. In the film, it is transported in a large square crate.

- In the film, the only residents of Nome who contract diphtheria are 18 children, but in reality, many more were infected, including adults.

- In reality, none of the mushers were ever knocked unconscious.[27]

- In the sequels, Balto becomes Jenna's mate and they have a litter of puppies who grow up and move on with their lives. In reality, however, Balto was neutered as a puppy and consequently never fathered a litter.[30]

- In the sequels, Balto continues living in Nome along with his family and friends, but in reality, Balto and his team spent the rest of their lives in the contiguous United States. After touring the vaudeville circuit for two years, Balto and his team were discovered chained to a sled at a small dime museum in Los Angeles.[36] A "Bring Balto to Cleveland" effort in Cleveland, Ohio, in March 1927[37] raised $2,000 to purchase the dogs, who were all moved to the Brookside Zoo (now the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo) to live their lives in dignity.[36][38] Balto resided there until his death on March 14, 1933, at the age of 14;[39] his body was taxidermied[40][41] and kept in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where it remains today.[42][43] After the movie's production was announced, the museum extended an invitation for Spielberg to meet Balto's mount,[44] which he declined.[45]

Release

[edit]The film was theatrically released in the United States on December 22, 1995, and then international theatres on January 13, 1996, when it first premiered in Brazil.[46] Its release was vastly overshadowed by that of Pixar Animation Studios' first feature film, Toy Story, which had premiered a month earlier.[47]

Box office

[edit]The film ranked 15th on its opening weekend and earned $1.5 million from a total of 1,427 theaters.[48] The film also ranked 7th among G-rated movies in 1995. Its total domestic gross was $11,348,324.[47] Despite being a disappointment at the box-office, it was much more successful in terms of video sales. These strong video sales led to the release of two direct-to-video sequels: Balto II: Wolf Quest and Balto III: Wings of Change being created, though neither sequel received as strong a reception as the original film.

Critical reception

[edit]Balto generally received mixed reviews from critics. On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 56% based on 25 reviews, with an average rating of 5.90/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Balto is a well-meaning adventure with spirited animation, but mushy sentimentality and bland characterization keeps it at paw's length from more sophisticated family fare."[49] The film received a "thumbs down" from Gene Siskel and a "thumbs up" from Roger Ebert in a 1996 episode of their television program At the Movies. Siskel found the film to be a weak attempt at aping Lady and the Tramp, criticizing the animation style as "sketchy", and the story as "all over the map, from the rousing adventure, to the sweet and cloying scenes", whereas Ebert liked the film, stating that despite not being in the "category of the great animated film" and the animation not being as strong as that of Disney, it was "adequate", the story was "interesting", and the film was a "nice, little children's adventure movie about a brave dog."[50]

Roger Ebert gave the film a three-out-of-four-star review, praising it as "a kids' movie, simply told, with lots of excitement and characters you can care about", and though he criticized Balto's refusal to fight Steele and stated that it compared poorly to Disney's output, he found it to be a satisfactory film in its own right.[51] Paul Merrill of Empire Magazine gave the film three out of five stars, commending the film as "enchanting, highly enjoyable and impressively crafted, not least for its adventurous 'camera work'", and praised the voice cast, "barnstorming" chase sequences and lack of "cheesy songs to slow proceedings down."[52] Nell Minow of Common Sense Media gave the film three out of five stars, calling it a "fun-but-tense fact-based film."[53] Stephen Holden of The New York Times praised the film for "avoiding the mythological grandiosity and freneticism that afflict so many animated features these days", and "making modesty a virtue."[54] Brian Lowry of Variety gave the film a more middling review, praising its pro-social messages and James Horner's "blaring" score, and finding the action sequences decent, but also criticized the humor as scant, and Balto himself as "rather blandly heroic."[55]

On the negative side, Nick Bradshaw of Time Out criticized the film as a "half-hearted animated feature" that "rambles on" with "second-hand plotting and characterization", and criticized the animation style as "TV-standard."[56] David Kronke of The Los Angeles Times criticized the film's historical inaccuracy and slow-paced premise establishment, criticized the animation as competent at best, and criticized the voice cast, stating that "even as voiced by [Kevin Bacon], Balto doesn't have the sort of charisma to get kids to truly root for him."[57] Rita Kempley of The Washington Post gave the film a negative review, calling it a "mushy animated melodrama", criticizing its storyline as "prosaic" and "sappy", and unfavorably comparing the film itself to Toy Story, as well as Disney's other output, and its artistry to Dogs Playing Poker.[58]

Home media

[edit]Balto was released on VHS and Laserdisc on April 2, 1996, by MCA/Universal Home Video in North America and CIC Video internationally. The VHS version was made available once more on August 11, 1998, under the Universal Family Features label.

The film was released on DVD on February 19, 2002, which includes a game, "Where is the Dog Sled Team?". This version was reprinted along with other Universal films such as An American Tail, An American Tail: Fievel Goes West and The Land Before Time. It was initially released in widescreen on Blu-ray for the first time exclusively at Walmart retailers on April 4, 2017, before its wide release on July 4, 2017.

Soundtrack

[edit]| Balto | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | December 5, 1995[59] October 29, 2018 (expansion) | |||

| Recorded | July 1995[60] | |||

| Studio | Abbey Road Studios, London Todd-AO Scoring Stage, Studio City (additional score; expansion only) Scrimshaw Sound, Nashville Quad Studios Nashville Skylab Studios, Nashville Sixteenth Avenue Sound, Nashville | |||

| Genre | Pop, modern classical, film score[61] | |||

| Length | 53:30 (original release) 78:55 (2018 expansion) | |||

| Label | MCA (1995) Intrada (2018) | |||

| Producer | James Horner | |||

| James Horner chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Balto | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| LetsSingIt | |

| Filmtracks | |

Balto: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack contains the score for the film, composed and conducted by James Horner, and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.[61] The soundtrack was released on December 5, 1995, by MCA Records. It includes the film's only song, "Reach for the Light" performed by Steve Winwood. The original album release went out of print when MCA Records went out of business in 1997.

A limited edition expansion of the soundtrack album was released by Intrada Records on October 29, 2018. This release includes newly remastered versions of the tracks from the original release and previously unreleased material, as well as alternate tracks that were ultimately unused in the finished film.[60]

Awards

[edit]The film received four Annie Award nominations, including Best Animated Feature, as well as a Young Artist Award nomination, but lost to Toy Story and A Pinky and the Brain Christmas.[63][64]

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annie Awards[63] | Best Animated Feature | Balto | Nominated |

| Best Individual Achievement: Producing | Steve Hickner | Nominated | |

| Best Individual Achievement: Production Design | Hans Bacher | Nominated | |

| Best Individual Achievement: Storyboarding | Rodolphe Guenoden | Nominated | |

| Young Artist Award[64] | Best Family Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy | Balto | Nominated |

Sequels

[edit]Two direct-to-video sequels that soon became a trilogy followed, made by Universal Cartoon Studios, with their animation done overseas by the Taiwanese studio Wang Film Productions, as Amblimation had gone out of business. Due to the significantly lower budgets and different production personnel of the sequels, Kevin Bacon, Bob Hoskins, Bridget Fonda, and Phil Collins did not reprise their roles in either of them. Instead, Bacon was replaced by Maurice LaMarche as the voice of Balto, Hoskins was replaced by Charles Fleischer as the voice of Boris, Fonda by Jodi Benson as the voice of Jenna, and Collins by Kevin Schon as the voices of Muk and Luk. In addition, aside from Balto, Boris, Jenna, Muk and Luk, none of the characters from the original returned for speaking roles in the sequels, and the few that did return were reduced to background characters in them.

The first sequel, Balto II: Wolf Quest, was released in 2002 and follows the adventures of one of Balto and Jenna's pups, Aleu, who sets off to discover her wolf heritage.[65] A few characters from the first sequel could not be brought back, owing to Mary Kay Bergman’s suicide in 1999, which also caused Balto II to be delayed for two years.

The second, Balto III: Wings of Change, was released in 2004. The storyline follows the same litter of pups from Balto II, but focuses on another pup, Kodi, who is a member of a U.S. Mail dog sled delivery team, and is in danger of getting put out of his job by Duke, a pilot of a mail delivery bush plane, while Boris finds a mate named Stella.[66]

Unlike the original movie, none of the sequels took any historical references from the true story of Balto, and neither contained live-action sequences.

See also

[edit]- Togo

- White Fang, Jack London's famous novel

- White Fang (1991)

- Silver Fang

- All Dogs go to Heaven

- Iron Will

- Anastasia

References

[edit]- ^ "Balto (1995)". Archived from the original on April 24, 2017.

- ^ "Balto (1995)". The Wrap. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ Balto at Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Lenburg, Jeff (1999). The Encyclopedia of Animated Cartoons. Checkmark Books. p. 166. ISBN 0-8160-3831-7. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ^ Phil Collins (2016). Not Dead Yet. London, England: Century Books. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-780-89513-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Exclusive interview with Balto director Simon Wells". animationsource.org. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ The Hollywood Reporter. Wilkerson Daily Corporation. 1995. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Reynolds, Christopher (1993). Hollywood Power Stats. Cineview Pub. ISBN 978-0-9638-7484-9. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ a b "BBC Two's 'The Making of Balto'". Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ "Kristof Serrand - ANIMATION MasterClass". YouTube. Pixi-Gags. 22 March 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "BALTO - Quadruped Drawing MasterClass". YouTube. Pixi-Gags. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 14 May 2024.

- ^ "SPACING & WEIGHT - Animation Lecture". YouTube. Pixi-Gags. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Lyons, Mike (January 1996). "Spielberg Apes Disney: Balto". Cinefantastique Volume 27. No. 4–5.

- ^ Smith, Mason (April 24, 2014). "[MINI INTERVIEW] Steve Hickner, Producer for Amblimation's 'Balto'". Rotoscopers. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Researching Nome's appearance". animationsource.org. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on June 27, 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ "Ken Keys interview". animationsource.org. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Emmer, Michele (July 25, 2006). Matematica e Cultura 2006 [Mathematics and Culture 2006] (in Italian). Springer Milan. ISBN 978-8-8470-0465-8. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Staff, Playback (August 1, 1994). "News Briefs". Playback. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "A. Film Theatrical Feature Film Productions History". A. Film.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d "The Hollywood Reporter Animation Special Issue". The Hollywood Reporter. January 24, 1995. pp. S-52. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d Weiss, Josh (November 27, 2023). "BALTO DIRECTOR ON "LITERAL UNDERDOG STORY" THAT CLOSED OUT ERA OF SPIELBERG-PRODUCED ANIMATION". Syfy. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Lenker, Maureen Lee (July 31, 2022). "City on a Hill star Kevin Bacon reflects on Apollo 13 vomit comet, dancing in Footloose, Tremors, and more". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 22, 2023.

- ^ Gearan, Hannah (July 30, 2024). ""What's The Matter With Him": How Steven Spielberg Recommendation Got Brendan Fraser Recast In 1995 Animated Movie". Screenrant. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ Wygant, Bobbie (5 September 2022). "Bridget Fonda "Balto" 12/9/95 - Bobbie Wygant Archive". YouTube. The Bobbie Wygant Archive. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Angel, Jack (June 12, 2012). The Book of Jack. Abbott Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781458203908. Retrieved 16 August 2024.

- ^ Deese, Frank. "Screenwriting Career". Frank Deese. Retrieved 4 October 2024.

- ^ a b Aversano, Earl. "Balto - Balto's True Story". Archived from the original on 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "The True Story of Balto - Facts". Animation Source. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "Balto - Balto'S True Story". Baltostruestory.net. Archived from the original on 2021-12-25. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- ^ a b Clifford, Stephanie (12 February 2012). "Spirit of a Racer in a Dog's Blood". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Aversano, Earl. "Togo - Balto's True Story". Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ a b Ingram, Simon (19 May 2020). "When a deadly disease gripped an Alaskan town, a dog saved the day – but history hailed another". National Geographic. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (2015). Leonhard Seppala: the Siberian dog and the golden age of sleddog racing 1908-1941. Pictorial Histories Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57510-170-5. OCLC 931927411.

- ^ Seppala, Leonhard (2010). Seppala : Alaskan dog driver. Ricker, Elizabeth M. [Whitefish, Mont.]: [Kessinger Publishing]. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-4374-9088-6. OCLC 876188456.

- ^ Reamer, David (1 March 2020). "Togo was the true hero dog of the serum run; it's about time he got his due". Anchorage Daily News. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ a b DeMarco, Laura (January 18, 2015). "How Cleveland saved a hero". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. pp. C1, C6. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dog Lovers Rally to Aid Balto Fund". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. March 2, 1927. pp. 1, 6. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Carman, Diane (February 1, 1985). "Balto: The Forgotten Hero". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. pp. 20–21, 24. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Career Ends". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. March 15, 1933. p. 16. Retrieved July 25, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Balto Lives Again". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. May 13, 1933. p. 24. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "At Natural History Museum: Balto, Savior of Nome, Makes New Bow". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. March 10, 1940. p. 56. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Sled Dog Relay That Inspired The Iditarod". History.com. 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- ^ Sell, Jill (October 26, 2023). "Organic interests: A trip to the new Cleveland Museum of Natural History Visitor Hall". FreshWater Media, LLC. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Drexler, Michael (January 7, 1994). "Hey, Spielberg, your heroic dog's right here". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland, Ohio. pp. 1A, 8A. Retrieved July 20, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Musarra, Russ (April 6, 1998). "Cleveland museum to stuffed sled dog: Stay!". The Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. pp. A1, A8. Retrieved July 22, 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Balto (1995)". Internet Movie Database. 22 December 1995. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ a b "1995 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "Balto - Box Office Data, DVD Sales, Movie News, Cast Information - The Numbers". Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "Balto - Rotten Tomatoes". Flixster. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- ^ "The Juror, Balto, White Squall, Nico Icon, French Twist, 1996". Siskel and Ebert Movie Reviews. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Balto Movie Review & Film Summary (1995)". Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ Merrill, Paul (January 1, 2000). "Balto Review". Empire Online. Empire Magazine. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Minow, Nell (September 23, 2010). "Balto Movie Review". Common Sense Media. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (December 22, 1995). "FILM REVIEW - A Dog-Eat-Dog World". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (December 31, 1995). "Balto". Variety. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Bradshaw, Nick (September 10, 2012). "Balto". Time Out. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Kronke, David (December 22, 1995). "MOVIE REVIEW: 'Balto' Tells a Wild Tale of Dogged Heroism". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (December 22, 1995). "Balto". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Filmtracks: Balto (James Horner)". Filmtracks. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b Neckebroeck, Kjell (30 October 2018). "BALTO EXPANDED EDITION: OUR EXCLUSIVE REVIEW". James Horner Film Music. Retrieved 19 November 2023.

- ^ a b "James Horner - Balto (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) (CD, Album)". Discogs. 1995. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "Balto Soundtrack Album". LetsSingIt. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ a b "24th Annual Annie Awards". annieawards.org. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ a b "17th YAA - 1995". youngartistacademy.info. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ "Balto: Wolf Quest (Video 2002)". Internet Movie Database. 19 February 2002. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- ^ "Balto III: Wings of Change (Video 2004)". Internet Movie Database. 30 September 2004. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

External links

[edit]- Balto: Universal Studios – Restored version of the original 1995 official Balto site.

- Balto at IMDb

- Balto at Rotten Tomatoes

- Balto at AllMovie

- Balto – Keyframe – the Animation Resource

- Balto III: Wings of Change at IMDb

- Balto III: Wings of Change at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1995 films

- 1990s adventure films

- 1990s American animated films

- 1990s British animated films

- 1990s British films

- 1990s children's animated films

- 1990s English-language films

- 1990s historical adventure films

- 1995 animated films

- 1995 children's films

- Adventure films based on actual events

- Amblin Entertainment animated films

- Amblin Entertainment films

- American adventure films

- American children's animated adventure films

- American children's animated films

- American films based on actual events

- American films with live action and animation

- American historical adventure films

- Animated films about children

- Animated films about polar bears

- Animated films about geese

- Animated films about dogs

- Animated films about wolves

- Animated films based on actual events

- British adventure films

- British films based on actual events

- British films set in New York City

- British historical adventure films

- Films directed by Simon Wells

- British films with live action and animation

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in 1925

- Animated films about talking animals

- Animated films set in Alaska

- Films set in Manhattan

- Mushing films

- Northern (genre) films

- Universal Pictures animated films

- Universal Pictures films

- Animated films set in the 1920s

- Animated films about grizzly bears

- Balto

- English-language historical adventure films