Badajoz bastioned enclosure

| Badajoz bastioned enclosure | |

|---|---|

| Perimeter of old Badajoz in Spain | |

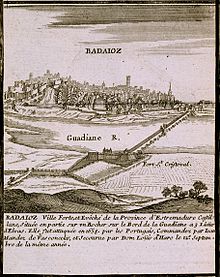

Plan of the siege that the rebel put on the city of Badajoz (Planta del sitio que el revelde puso a la ciudad de Badajoz, sic) by Kungl Krigsarkivet in 1658. | |

| Coordinates | 38°52′55″N 6°58′08″W / 38.881914°N 6.968992°W |

| Type | Fortified and bastioned enclosure |

| Area | 6541 m of preserved wall (including the citadel-castle) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Badajoz City Council |

| Condition | Restored; in very good condition |

| Site history | |

| Built | 17th to 18th century (prolonging an earlier defensive system from the 9th to the 16th century) |

| Built by | System of Sébastien Le Prestre, Marquis de Vauban or simply Vauban. |

| Materials | According to the different rehabilitation, masonry, dimension stone, brick and concrete |

| Bien de Interés Cultural as Conjunto histórico | |

The bastioned system of the Spanish city of Badajoz consists of a military fortification formed by a set of defensive walls, city gates, bridges, forts, towers, bastions, hornworks, moats, tunnels, and ravelins, among other defensive elements. It was built between the 17th and 18th centuries, following the defensive construction theories popularized by the French military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre, better known as the Marquis de Vauban, as an extension of a previous defensive enclosure that protected this border town.[1]

Since its founding by Ibn Marwan—over an earlier Visigothic settlement, as Badajoz has been inhabited since prehistoric times—the city has maintained a stronghold character up to the 20th century. Its strategic location at the crossroads of two major routes: one from Castile to Andalusia, and the other from the plateau to Lisbon, along with its status as a border city with Portugal, has led to both advantages for Badajoz's development and numerous conflicts involving various armies over the centuries. Consequently, the city has been protected by several defensive enclosures.[2]

The first fortifications were carried out by Ibn Marwan, who ordered the erection of mortar walls. This was followed by restoration work undertaken by Abd Allah Ibn Muhammad Ibn Abd al-Rahman, the founder's grandson, in 913. Later, in 1030, Abdallah ibn Al-Aftas, the first Aftasid king of the Taifa of Badajoz. In 1169, the Alcazaba was built, closely resembling the present structure, with some elements dating back to the Almohad period. The final Muslim restoration was commissioned by Abu Yahya ibn Abi Sinan at the beginning of the 13th century.[3]

After the conflicts between Castile and Portugal in the 14th century, relations between the two regions were normalized, leading to a period of peace that lasted nearly two and a half centuries. However, in 1640, when Portugal gained independence from the Spanish Monarchy, Badajoz became a border city. Due to its strategic importance, the Castilian authorities recognized the need to enhance its defenses. Consequently, both the Crown and the authorities of Badajoz decided to undertake significant fortification works. Despite the various options proposed by military engineers, the decision was made to implement the Vauban system. The fortification efforts were marked by improvisation amid economic difficulties, and the reforms and improvements were made incrementally to the existing defenses.[4]

Background

[edit]

The city of Badajoz, specifically the oldest area, located in the highest part of the promontory called Cerro de la Muela, was protected by an enclosure built during the Islamic period, with its fortress known as the Alcazaba. During Islamic times, Badajoz was encircled by a defensive wall that safeguarded the al-qasbah (ksar), the citadel, which served as the administrative center and residence of the rulers of the Kingdom of Badajoz—one of the largest taifas of the Iberian Peninsula. This area housed the Alcázar, the mosque, and one of the era's largest libraries. The defensive wall underwent several extensions over time. The buildings within the enclosure reflect its varied functions across different periods: as an Islamic citadel with various extensions until it resembled the so-called "Cerca Vieja" (9th–13th centuries); as a Christian late medieval castle featuring the first Badajoz Cathedral built on the site of the former mosque and various "fortified houses" for defense (13th–16th centuries); and as part of the modern fortifications (17th–19th centuries), which included different religious buildings, secret passage, and cisterns reused over time.[5]

The city of Badajoz continued to expand beyond its original walls, particularly to the west and south, where the terrain was flatter. This expansion was encircled by a medieval wall of rammed earth, likely of Almohad origin, with subsequent extensions. By the end of the 15th century, a late medieval pentagonal fence, contemporary with the Catholic Monarchs, was constructed. This fence connected with the Palmas Gate near the Palmas Bridge and the Pajaritos Gate, both dating from the 16th century. Inside these walls were the neighborhoods forming the historic district. However, these defenses proved insufficient against the advancing artillery technology of the following century.[6][7] In 1642, amidst the conflict with Portugal, a series of isolated and improvised defensive structures were initiated, starting with the fort of San Cristobal. Located on the right bank of the Guadiana River, north of the city, on a significant promontory known as Orinaza Hill, this fort was considered the first of its kind for defensive fortifications. It protected the bridgehead, a crucial strategic element, as the bridge served as the main entrance to Badajoz. Defensive measures were taken to protect the bridge, including the demolition of several arches, the replacement with a drawbridge of three spans, and the construction of parapets for the garrison's defense.[8]

Soon after, the Pardaleras Fort was constructed at the southern end of the city. Additional defensive elements, such as moats and walls, were added in a somewhat haphazard manner, which reduced their effectiveness. Inadequate materials and the lack of order in these constructions led to significant losses of land and buildings. At the end of the 17th century, between 1690 and 1700, work began on a bastioned fortification. This new defensive wall extended from the medieval wall along the left bank of the Guadiana River to the bastions of San Vicente and Palmas Gate. It then turned west and south, passing through the bastions of San José, Santiago, Santa María, and Trinidad Gate, before reconnecting with the defensive wall protecting the Alcazaba. According to existing military cartography, the watchtowers from the Islamic period remained in use until the War of Independence. Of the numerous watchtowers Badajoz once had, primarily from the 12th century, only remnants of five are preserved, including the Espantaperros Tower and the Tower of Los Rostros.[1]

- Gallery

-

Abarlongada Tower from the chemin de ronde of the city defensive wall

-

Hanged Men Tower

-

Albarrana Tower

-

Front view of the Espantaperros Tower

-

Interior of the Alcazaba

-

Exterior of the Alcazaba

-

Interior door of the Alcazaba

-

Defensive walls and chemin de ronde of the Alcazaba of Badajoz

-

Sapur tombstone

-

Capital Gate

-

Capital Gate (back)

-

Curved gate

-

Views of the Alcazaba and the town halls from Plaza Alta

-

Carriage Gate or Yelbes Gate

-

Alcazaba Access

-

Lintel door

-

Alcazaba of Badajoz wall

-

Palace of the 16th century (Provincial Archaeological Museum)

-

Remnants of the Mosque-Cathedral (next to the old Military Hospital)

-

Alcazaba parapet

-

View from inside the Alcazaba

History

[edit]

Portugal and Castile engaged in a series of confrontations during the 14th century. In 1580, Philip II relocated the Court and the majority of his army to Badajoz, where he resided for eleven months, effectively annexing Portugal into the Hispanic Monarchy. Tensions concerning Badajoz resurfaced in 1640 due to its proximity to the border, as a result of the Portuguese uprising against the Crown of Castile.[9]

The construction of the bastioned enclosure began in the 17th century, replacing a previous defensive system. This development was necessitated by the need to defend Badajoz, the seat of the General Captaincy of the Royal Army of Extremadura, amidst the hostilities that led to the Portuguese Restoration War. This conflict aimed to secure Portugal's independence from Spain. Consequently, Badajoz solidified its role as the capital of the Province of Extremadura and became a significant strategic location for both Spanish and Portuguese interests. The war persisted from 1640 to 1668 when the Treaty of Lisbon recognized Portugal's full independence from Spain.[10]

Due to its frontier location, the Badajoz Cathedral—constructed between the 13th and 18th centuries—resembles a fortress, featuring strong walls, battlements, and a prominent bell tower. Declared a Historic-Artistic Monument in 1931 and classified as an Asset of Cultural Interest, it stands out as a unique structure from its era. The Diocese and Bishopric of Badajoz date back to the 10th century, and the cathedral currently holds the rank of Metropolitan Cathedral. It houses Islamic pottery from the 10th century and the Metropolitan Museum of the Cathedral. Nearby is the historical archive.[10]

The geographical features of Badajoz's terrain have historically marked it as a site of military and strategic importance. This significance made it a key point in the Spanish defensive system, especially given Portugal’s strong defensive system of Elvas. Badajoz thus became a major stronghold on the border with Portugal. Its location, nearly at the same latitude as Lisbon and approximately equidistant from Madrid and Lisbon, though somewhat farther from Madrid, further accentuated its strategic value.[11][12]

- Gallery

-

Exterior of the Cathedral-Fortress of Badajoz

-

Cathedral Door

-

Window detail

-

Door of the cathedral crypt

-

Top of the dome of the Church of the Conception, next to the tower of the Cathedral

The onset of defenses

[edit]

The bastioned enclosure was constructed on the foundations of the old medieval walled enclosure, which dated from the 9th to the 15th centuries and remained in existence until the 17th century. Some sections of the medieval wall were preserved, such as those near the bastion of La Trinidad and the bastion of Santiago. The old medieval wall, or "old fence", which extended from the current citadel, had become outdated due to the advancements in artillery technology used by the Portuguese army. After nearly two and a half centuries of neglect, it had deteriorated and become obsolete. In 1643, the Count of Santiesteban wrote to Secretary Pedro Coloma regarding the defensive structures in Badajoz. He noted that, at that time, Extremadura lacked secure defenses, provisions, artillery, and other weapons. Badajoz appeared to have the minimum defensive conditions necessary, but the existing walled enclosure was deemed ineffective. The only part of the fortifications that might have had adequate defensive capabilities was the upper section occupied by the Alcazaba. Consequently, it was recommended that new defensive works be initiated in that area.[13][14]

On the other hand, the Marquis of Torralbo wrote to the king in the following terms:

The inhabited enclosure of the Alcazaba encircled by the Almohad wall was with the fallen parapets and destroyed the faussebraye, as well as the doors, without closing or rake.

He concluded by saying that it was within the reach of artillery, for which the rammed earth walls were ineffective:

... for it is within musket range from the fort of San Cristobal.[15][14]

Gradually, the old defensive wall was replaced by a new fortification that began at the Muslim citadel, followed the left bank of the Guadiana River, and then turned west and south, where the bastions of San Vicente and Palma Gate were constructed. The construction continued westward, southward, and eastward, with the bastions of San José, Santiago, San Roque, Santa María, and Trinidad being added in succession. This new defensive system eventually connected to the old Alcazaba in the northeast via the bastion of San Pedro.[10]

The newly built defensive elements were adapted to contemporary military engineering trends. The walls were made lower and wider to withstand cannon fire, and large bastions were introduced. The curtain walls were buttressed rather than vertical to deflect cannonballs upward. Additionally, half bastions were placed to guard the access gates, bartizans were added at the vertices where two curtain walls met, and features such as moats, lunettes, and ravelins were included to hinder enemy actions. Despite the robust nature of these defenses, the walls were also adorned with a semicircular stone facade, with its curved part facing outward.[11]

The defensive system followed the design principles established by the French military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre, better known as the Marquis de Vauban.[16]

Elements

[edit]

The bastioned enclosure is composed of several defensive buildings such as the curtain wall of the defensive walls, the gates, designed to allow and control the entry and exit of the inhabitants, the bastions consisting of pentagonal constructions, which join two consecutive lines of defensive wall on the inner side of the pentagon, the forts located on the outside of the defensive walls and that were the first line of defense of the population and the ravelins that are triangular fortifications located in front of the body of the main fortification –generally on the other side of a moat– whose objective is to divide an attacking force and to protect the curtain wall of the defensive walls using crossfire. There are also other defensive elements such as moats, foothills, drawbridges, escarpments, and various smaller buildings either attached to or independent from the main enclosure.[10]

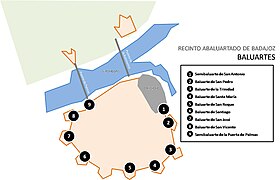

Bastions

[edit]

A bastion or bulwark is a fortified redoubt that projects outward from the main body of a fortress, generally located at the corners of the curtain walls, as a strong point of defense against the enemy. It may have openings in its walls such as arrowslits, embrasures, etc. Bastioned fortresses usually have a polygonal plan and low height to offer the smallest possible impact surface to the cannon projectiles and are slightly inclined so tha they do not impact frontally and bounce upwards. They usually have a moat in front and also foothills to increase their defensive power.[17]

There are different names to define each of the bastions according to the type and form of construction, such as "pincer bastion", "cut bastion", "orillon bastion", "prominent bastion", "double bastion", "irregular bastion", "full bastion", "regular bastion", "simple bastion", "empty bastion", etc.[18]

Semi-bastion of San Antonio

[edit]

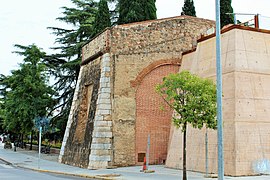

It is number 1 on the Plan of Bastions. This semi-bastion joined the primitive alcazaba by its eastern zone with the rest of the bastioned enclosure. For its construction, the old Alpendiz Gate was closed. To fill it with earth and stones on the inside so that it could withstand the impacts of modern artillery, the materials of the Torre Vieja (Old Tower) were used, so it was left bareheaded. It was a tower that was part of a fortified enclosure with which it was communicated, although generally exempt from the defensive wall. The remnants of the Torre Vieja were concealed by this enclosure and remained hidden within the bastion. A small door was opened to replace the Alpendiz Gate, serving as a gateway.[19]

It was built in the neighborhood of San Salvador and nowadays it is next to a modern park. When the Torre Vieja was removed, it was buried, but in excavations carried out at the end of the 20th century, a large part of it was discovered.

A tour of the exterior from the southern part of this bastion to its junction with the defensive wall of the Alcazaba, facing east, provides a view of its historical context and structure.

- Gallery

-

Southern curtain wall with a mark of artillery bullet impact

-

Southern curtain wall with marks of artillery bullet impacts

-

Southern curtain wall very elevated on rock

-

Old defensive walls outside the bastion on the east side

-

Outer wall, of lesser size

-

Curtain wall of the bastion, old defensive walls and, in the middle, the moat

-

Eastern curtain wall and, in the corner, another one to the north. In the background another to the east

-

Moat between the bastion and the old defensive wall

-

Northern curtain wall elevated on rock. In the background the Espantaperros Tower

-

Three curtain wall of the bastion next to the junction with those of La Alcazaba

-

High area of the bastion with embrasures in the upper part

-

Coat of arms over the Merida Gate

-

Open gate when the Alpendiz Gate was closed

-

Entronque of the bastion with the defensive wall of La Alcazaba

-

Diagram of the Old Tower hidden by the bastion with upper embrasures

-

View of the interior of the bastion from its highest point

-

View towards Merida from the upper part of the bastion and embrasures

-

North and east curtain wall of the junction with La Alcazaba

Bastion of San Pedro

[edit]

It has the number 2 in the Plan of Bastions. It is located next to the "Semi-bastion of San Antonio" and before the one of Trinidad, in the eastern zone of the bastioned enclosure, in front of the Rivillas River. Between these two bastions is the Merida Gate. Its construction dates from the last decades of the 17th century, the same period as that of the bastion of Trinidad, making both the oldest bastions in the enclosure.[16] It had a series of bartizan of which only their bases remain, as well as embrasures at the top of the defensive wall, but at present there are no remains of them. In 1772, the right flank of the bastion was provided with a series of arrowslits connected by a gallery for the circulation of the riflemen. The interior zone is very deteriorated.[20]

The bastion played a crucial role during the War of the Spanish Succession. Badajoz endured several sieges during this period, the most notable being in 1705 when supporters of Archduke Charles of Austria besieged the city. The defenders, consisting of French and Spanish troops loyal to Philip of Anjou, faced the attackers, who established their artillery batteries across the Rivillas stream, near "La Picuriña" and the hermitage of San Roque.[21]

The attackers aimed to exploit the city's weakest defensive side and breach the defensive wall to gain entry. They concentrated their fire on the bastion of San Pedro, succeeding in creating a breach. However, the arrival of French reinforcements discouraged them from proceeding with the assault. The experience from this conflict prompted the Badajoz defenders to enhance their fortifications in this area. They constructed a ravelin, known as the Ravelin of San Roque, and a fort outside the defensive walls, initially called the Fort of the Prince and later renamed the Fort of the Picuriña.[21] During the Peninsular War, the redcoats of the future Duke of Wellington, led by General Thomas Picton of the 3rd Division, entered this area in 1812 following the third assault for the liberation of Badajoz. This assault resulted in significant casualties. To commemorate this battle, the soldiers engraved the year "1812" on one of the curtain walls of the bastion by removing the stones to expose the date. The impacts of cannonballs from the War of Independence remain visible on the bastion's corners.[22]

- Gallery

-

Beginning of the bastion in its northeast zone

-

Several walls on the east flank

-

Several walls on the east flank

-

Angled walls

-

Rehabilitated interior area of the bastion with door and upper gate

-

Large south-facing wall

-

Old sketch of the bastion with the Rivillas stream in front of it

Bastion of Trinidad

[edit]

It has the number 3 in the Plan of Bastions. It is located in the northeast corner of the walled enclosure, where the medieval tower called Torre del Canto was located, between the bastion of Santa María and the bastion of San Pedro. To the left of this section, in the old map entitled Plan of the Square and Castle of Badajoz, capital of Extremadura and border with Portugal, drawn by Jean Gabriel de Mercier de Chermont in 1775, it is observed that in front of the bastion and protecting its walls there is a counterguard marked with no. 22. It is also observed that the Convent of the Trinity, marked with no. 46, occupies almost the entire interior of the bastion.[23]

This bastion, along with the bastion of San Antonio, is one of the oldest in the bastioned enclosure of Badajoz, both constructed in 1680. The bastion's name derives from the Trinitarian convent that existed within it before its destruction. The convent, dating back to the 13th century, influenced the bastion’s design. Some engineers, including Luis de Venegas, proposed moving the defensive wall to place the convent outside the walled enclosure. Others, such as Francisco Domingo, advocated for including the convent within the bastion, which was ultimately adopted. This decision faced criticism from military engineers responsible for the city's defense, as the area was lower and more vulnerable to attacks from the heights of "La Picuriña." Only remnants of the convent remain, as its stones were used in the bastion's reconstruction. The bastion originally featured bartizans for surveillance, but none are extant today. The embrasure openings and arrowslits for rifles at half-height of the curtain wall are still visible, and there was an interior corridor along the length of the loopholes for communication between riflemen and the interior of the enclosure.[24]

Luis de Venegas's 1677 plan illustrates various proposed layouts for the defensive wall facing the Rivillas stream. The medieval wall is marked in red, the layout that excluded the convent is marked in green, and the layout that included the convent inside the enclosure is marked in black. The covered way to the outside is highlighted in yellow.[25]

The bastion was destroyed during the French sieges of 1811 and 1812 in the War of Independence and was subsequently rebuilt in the last third of the 20th century.[26]

Within the public park constructed on the site, several statues by Juan de Avalos are displayed: a sculptural group titled "Fallen Hero" and four bronze statues of the four evangelists, similar to those in the Valley of the Fallen.[27]

- Gallery

-

Interior of the bastion with embrasures on the defensive wall

-

Communication opening between the chemin de ronde and the interior of the bastion

-

Window of communication from the interior with the parapet

-

Large curtain wall with embrasures and arrowslits

-

Ramp up and access to the parapet

-

Interior accesses to the chemin de ronde and postern

-

East flank. Beginning of the bastion seen from the inside

-

View where the opening for vehicular traffic was made

-

Beginning of the bastion; eastern curtain wall

-

Spillway or sewer at the bottom of a curtain wall

-

Detail of spillway or sewer in the lower part of a curtain wall

-

Embrasures and cannons in position over the Trinidad Gate

-

Inner area of the east of the bastion

-

Inscription on the exterior of the bastion's curtain wall

-

Access ramp to the chemin de ronde from the exit door

-

East flank. Beginning of the bastion seen from the bastion of San Pedro

-

Wall and beginning of the bastion. Eastern curtain wall

Bastion of Santa Maria

[edit]

It has the number 4 in the Plan of Bastions. It is flanked by the bastions of La Trinidad and San Roque. It was also known as "La Laguna" due to the outer moat, which could be flooded by water from small dams on the Rivillas stream, thereby enhancing its defensive capability. This feature effectively transformed a large portion of the walled city into an island of difficult access.[28]

Constructed in the 17th century, the bastion was severely damaged during the French siege and assault on Badajoz in the War of Independence in 1812. The forces of Lord Wellington, including the 3rd Division and the Light Division, captured the city but left the bastion in ruins. Remnants of a cemetery, where British soldiers who fell in combat were buried, are located between the moats of this bastion and that of La Trinidad.[28]

The bastion was subsequently rebuilt in the 18th century. As a memorial to the 1812 destruction, the date "1812" was engraved on both this bastion and the one at La Trinidad, using the cannonball impacts that formed the numbers. The bastion originally featured fourteen cannon embrasures: four at the front and five on each side. Of the bartizans that once stood at each corner of the curtain walls, only two remain. The reconstruction included rifle galleries for enhanced defense.[29]

Currently, the bastion is surrounded by buildings, particularly in the southeastern area, and is obscured by extensive undergrowth, making it largely hidden from public view.[29]

- Gallery

-

Corner curtain wall, bartizan and spillways in low area

-

Degraded corner bartizan

-

Curtain wall with embrasures and date 1812 engraved with the shots fired with cannonballs by Wellington's troops to commemorate the assault on the two bastions.

-

Corner curtain walls with good masonry, bartizan and spillways in the lower zone.

-

Detail of the date 1812 engraved with shots fired by British artillerymen to commemorate the assault on the two bastions.

-

Exterior wall. Bullring in the background

-

South and west curtain walls at the corner with bartizan

-

Two curved corner curtain walls

-

Strong curtain wall to the east with bartizan in the background

-

Corner of ashlars and bartizan

-

Sharp south-east corner, of ashlars, and bartizan at the ends.

-

Detail of bartizan in south-west corner

-

Strong south curtain wall with bartizan in the background

-

Bartizan between south and west curtain walls

-

Monument to the Fallen in the War against France

-

Large south curtain wall with bartizan and embrasures

-

Perspective of large south and west curtain walls

-

Large west curtain wall with bartizan and embrasures

-

Weaker western and southern curtain walls

Bastion of San Roque

[edit]

It has the number 5 in the Plan of Bastions. It is located between the bastion of Santa María and the now disappeared bastion of San Juan, in the southern part of the bastioned enclosure and is bounded by Estadiu street and the Ronda del Pilar.[30] Originally constructed in the 17th century, it was reinforced during the 18th century with additional defensive features, including rifle and cannon embrasures. A total of sixteen embrasures were built: four at the front and six on each flank or curtain wall. The left flank was further equipped with rifle galleries and arrowslits to enhance its defensive capabilities.[10]

In 1818, a bullring was constructed within the bastion, but it fell into disuse with the advent of a more modern bullring in the 20th century and was subsequently demolished. The bullring was destroyed in 2006, and the site was replaced by the Conference Center of Badajoz.[30]

The image gallery depicts the bastion from the exterior, beginning near Pilar Gate, moving eastward, and then showing the structure from the opposite direction, now on the interior, returning to Pilar Gate.

- Gallery

-

Start-up of the bastion in Pilar Gate

-

Corner of south and west curtain walls

-

bartizan to the south

-

Southern and western curtain walls and bartizan at the junction

-

Auditorium protruding from a curtain wall

-

Detail of bartizan at the curtain walls junction

-

Southern curtain wall and bartizan in the background

-

bartizan at the junction of the eastern and southern curtain walls

-

East end with large openings for traffic

-

Western and southern curtain wall with front gracis

-

East end with large gap for traffic

-

Arrowslit detail

-

Detail of the interior of the bartizan

-

Gun port on a south curtain wall

-

Detail of the attack on the bastion of San Roque. Jacques Pennier, 1705

-

Detail of embrasure

-

Embrasure at the top

-

South flank and bartizan in the background

-

Junction of the bastion with Pilar Gate

Bastion of San Juan

[edit]The bastion of San Juan, which is number 5 on the Plan of Bastions, was located between the bastion of San Roque and the bastion of Santiago. It was entirely demolished in the 1950s to create road access to the center of Badajoz via Europa Avenue. The removal of the bastion led to the loss of several centuries of history associated with the bastioned enclosure of Badajoz.[30][31]

Known as the "Bastion of the Bomba", this bastion was in close proximity to the Pilar Gate. For many years, it housed a Cavalry barracks called Cuartel de la Bomba.[32] The area formerly occupied by the bastion was subsequently urbanized, with its main street initially named General Rodrigo Street in honor of the soldier who participated in the occupation of Badajoz during the Spanish Civil War. This name was later changed to "Avenida de Europa".[33]

Bastion of Santiago

[edit]

It has the number 6 in the Plan of Bastions. It is located at the end of Menacho Street, between the bastion of San Juan to the east, which has completely disappeared, and the bastion of San José to the west, all of them in the southern part of Badajoz. This bastion, which features a pentagonal plan, was constructed in the 17th century and underwent significant modifications in the 18th century. It includes an orillon, a semicircular element designed to defend the curtain wall between bastions and to protect the postern. Originally, the bastion was equipped with bartizans at all its vertices, although only the one in the orillon remains today.[34][10]

The bastion is also known as the "Bastion of Memory" in honor of General Menacho, who was killed in 1811 while defending Badajoz from French forces during the Spanish War of Independence.[35] An inscription commemorating Menacho was placed on the bastion in 1852 at the location of his death. The monument, designed by Captain Julio Carande and executed by marble workers Almendro and Zoido, was inaugurated on May 2, 1893. It featured marble from Alconera for the pedestal and staircases, marble from Borba for the main structure, and Italian marble for the inscriptions. Although the original four marble lions that were part of the monument are now missing, part of the monument remains preserved.[36]

In the late 19th century, an attempt was made to add a postern to the bastion, intended as a small service gate for easy communication with the outside and for storage purposes. However, it never fulfilled its intended role effectively.[37]

Recent construction activities, such as the development of a parking lot, uncovered sections of older curtain walls and an Arab cemetery from the 10th and 11th centuries. These historical finds have been preserved and are visible from specific vantage points on the northwest flank of the bastion and within the parking lot itself.[38]

The gallery of images shows the bastion starting from the outside, from its beginning, behind the Government Delegation, continuing towards the west and then showing it in the opposite direction, already on the inside, until arriving again at the beginning, on its southern flank.

- Gallery

-

Union of two curtain walls at the eastern end of the bastion

-

Night view of the strong south curtain wall with upper embrasures

-

South curtain wall at the junction with orillon and guard house

-

Orillon at western end with bartizan

-

Concave curtain wall at west end with upper embrasures

-

Continuation of the concave curtain wall with upper embrasures

-

Detail of a decommissioned bartizan on the west side of orillon

-

Orillon in the west zone, defensive walls, embrasures and bartizan

-

Orillon west with remains of bartizan

-

Junction of concave defensive wall with old defensive wall

-

Remains of defensive wall at the western end

-

Detail of welt on the top of the curtain wall

-

Detail of the joint at the crown of the south and west curtain wall

-

West end with old defensive wall recently uncovered

-

Embrasures on the concave defensive wall of the west flank

-

Monument to G. Menacho

-

Detail of the base of the monument to General Menacho.

-

Detail of the base of the monument to General Menacho.

-

Detail of the base of the monument to General Menacho

-

Museum of the Carnival of Badajoz in the postern

-

Public parking at the postern

-

Detail of a deconstructed bartizan

-

Location plan of the bastion on enclosure

Bastion of San José

[edit]

It has the number 7 in the Plan of Bastions. It is flanked by the bastion of Santiago on the south, and by the bastion of San Vicente in its southwest wing. It is not directly connected to the Bastion of Santiago, as the curtain wall that linked them was demolished to accommodate the construction of Columbus Avenue, which connects the center of Badajoz with its expansion area to the west. However, the curtain wall linking it to the Bastion of San Vicente remains intact and in excellent condition since its construction, which began in the latter part of the 17th century. This curtain wall was later renovated and extended in the 18th century and received additional reinforcement near the top of the curtain walls. The bastion was equipped with eight embrasures: four facing the Bastion of Santiago, two towards the ravelin, and two towards the curtain wall connecting it with the Bastion of San Vicente.[39]

Between 1772 and 1777, many of the bastions, including the Bastion of San José, were reinforced to increase their thickness and, consequently, their resistance to artillery fire. The Bastion of San José was provided with two "riflemen's galleries", also known as "Galería Aspillerada" due to the arrow slits used by riflemen. It is the only bastion that retains both galleries, though the one on the left flank is almost completely sunken. Additionally, a section of the covered path surrounding the entire bastion is preserved; this path's defensive purpose was to detect the enemy from a distance, allowing defenders to remain hidden. Thus, it served as the first line of defense. Although this bastion effectively fulfilled its defensive role, it was involved in relatively few sieges despite the city's numerous conflicts, and it was the area least affected by enemy artillery.[36][40]

The route for inspection begins at the southern end of the bastion, near the Bastion of Santiago, separated by Avenida de Colón, and proceeds to the southwestern end before continuing through the interior of the bastion.

- Gallery

-

Southern and western curtain walls with corner bartizan

-

Union of the strong southern and western curtain walls

-

Strong north-western curtain wall

-

Curtain wall crowning detail

-

Bartizan and moat

-

Detail of bartizan

-

bartizan, moat and ravelin in the background

-

South-western corner of the bastion

-

Strong north-eastern curtain wall

-

Detail of the grove under the embrasures

-

Interior of the bastion with embrasures

Bastion of San Vicente

[edit]

It has the number 8 in the Plan of Bastions. It has on its left flank, to the west, the bastion of San José, and on the right, to the northwest, the semibastion of Palmas Gate. Constructed in the 17th century, it provided defensive fire coverage for the northwest section of the Bastion of San José. The bastion preserves an orillon at its left end in excellent condition. Along with the Bastion of Santiago, it is one of the few remaining examples of this defensive feature. The bastion features multiple embrasures for large-caliber artillery, located on the orillon, the poterna, and the flank facing the Guadiana River. It also includes bartizans at the corners of the curtain walls and on the orillon. This bastion, along with the Bastion of San José, is among the most noteworthy for visitors due to its extensive array of historical defensive elements.[41]

- Gallery

-

Left flank. Union of the western and northern curtain walls

-

Detail of arrowslits for rifles

-

Access door to the moat from the postern

-

Chapel dedicated to the Our Lady of Solitude, patron saint of the city, with an image of her inside. It was built moving in its entirety the facade of the old chapel located in the current square of the same name where today stands the building of La Giraldilla and was attached to the curtain wall of the defensive wall between the bastions of Saint Joseph and Saint Vincent

-

Inscription on tombstone, outside

-

Exit from the pothole to the moat and riflemen's gallery to the left

-

Orillon that protects the entrance to the postern, bartizan and embrasures

-

Orillon that protects the entrance to the postern, bartizan and embrasures

-

Details of bartizan, embrasures and curtain wall on north side

-

Detail of curtain wall between bartizan and upper embrasures

-

Northwestern curtain wall and park executed in the moat

-

Northwest curtain wall between two bartizan

-

Powerful north curtain wall

-

Descent to the postern from inside the bastion to the moat

-

Postern Gate

Semi-bastion of Palmas Gate

[edit]

Also known as Baluarte de las Lágrimas (Bastion of Tears), it is number 9 on the Plan of Bastions. It is located on the left flank of Palmas Gate. The Palmas Gate had a series of defensive elements among which was this semi-bastion which is the only building that remains. The semi-bastion is characterized by two curtain walls forming an angle: one oriented towards the Guadiana River and the other towards the west, connecting at its end with the Bastion of San Vicente. The western curtain wall includes three embrasures in its upper section designed to provide defensive fire and protect against potential assaults on the moat of the Bastion of San Vicente.[42][43]

The inspection route starts at the junction with the Bastion of San Vicente, progresses outward to Palmas Gate, and then returns through the upper area of the bastion, moving in the opposite direction.

- Gallery

-

Continuation curtain wall of the Bastion of San Vicente

-

Continuation curtain wall of the Bastion of San Vicente with upper embrasures

-

Three "Z" curtain walls with intermediate bartizan

-

One of the curtain walls of the "Z" with bartizan and exit from the postern to the moat

-

Strong northern curtain wall

-

End of north curtain wall with embrasures and descent to the moat

-

Descent from inside the defensive wall to the moat. Detail of the upper wall

-

Final gates of the semi-bastion

-

Inner area of the defensive wall near the Palmas Gate

-

Crimp corner between the outer curtain wall and the curved wall next to the gate

-

East end of the semi-bastion next to the Palmas Gate

-

Interior of the semi-balustrade with embrasures, near the Palmas Gate

-

Curtain wall to the west with embrasures defending the moat and Palmas Gate in the background

-

Western curtain wall with embrasures defending the moat and east descent

-

Curtain wall with embrasures and arrowslits for rifles

Gates

[edit]

The gates of the bastioned enclosures were openings in the curtain walls designed for the passage of people and vehicles, as well as for controlling access. Until the mid-20th century, these gates were opened at dawn and closed at dusk. They also served a fiscal function, as they were the locations where taxes, then referred to as tariffs, were collected on certain goods entering the city. In the final years of this tax collection practice, payments were made at the Palmas Gate on the side entrance road. However, prior to this, the collection took place at the midpoint of the Palmas Bridge, where two bartizans in the form of merlon towers were situated.[44]

Merida Gate

[edit]

The gate numbered 10 on the Plan of Gates is located in an area known as "Campillo", south of the Alcazaba.[45]

Initially, this gate was part of the original Almohad defensive wall from the 13th century, situated slightly farther east on a curtain wall of the Bastion of San Pedro. It provided access to the city via the old road from Talavera to Mérida, which is reflected in its name. However, access is required fording the Rivillas stream. When construction of the Vauban-style defensive system began in the 17th century, the gate's location was adjusted and it was repositioned to its current site, between the Bastions of San Pedro and San Antonio. The gate was flanked by two large square towers, one on each side, along with other defensive features.[46]

Despite this relocation, the gate became unusable because the new defensive works necessitated the use of a quarry located outside the gate. This created a steep, nearly vertical slope that rendered the gate inaccessible, leading to its being walled up. As of the early 21st century, it remains impracticable and inaccessible from the outside.[47]

A coat of arms of Great Britain is situated nearby as a tribute from the Cortes of Cadiz to Lord Wellington for his role in the 1812 conquest of Badajoz from the French. Additionally, it honors the Count of Montijo, then Captain General of Extremadura, who was a significant proponent of the bastioned enclosure's construction. Above the gate, a chapel dedicated to the Virgin of Tentudía, now vanished, was once built.[45] The interior façade featured an area for the gate's guards and the aforementioned chapel. The arch of the exterior façade is constructed with large granite stones, some of which are wedge-shaped and were salvaged from the old gate. At the upper part of the arch, there are stone blocks bearing the coats of arms of King Charles V—originally placed on the gate—and the Count of Montijo, which replaced the coat of arms of Badajoz.[48]

- Gallery

-

Interior side view

-

Exterior view from the first defensive barrier

-

View of Badajoz drawn by Pier Maria Baldi in 1668. The Merida Gate was then in its former position

-

Coat of arms of Charles V above the gate

-

Exterior view of the door with no possibility of access due to the great difference in level

-

View of the defensive wall and gate

Gate of La Trinidad

[edit]

Designated as number 11 on the Plan of Gates, it is situated adjacent to the San Roque Bridge, at the beginning of the Pilar roundabout, and directly in front of the Monument to the Fallen Hero. It provides access to the Bastion of the Trinity. Constructed in 1680 using granite ashlars, the gate is crowned on the exterior with the coat of arms of Charles II, reflecting the period of its construction. The defensive wall above the gate features several embrasures for large-caliber artillery. Like other earlier gates, this one was demolished as part of the construction of the new defensive system, and a similar gate was built in its place, which remains today. Unlike most gates, which are positioned centrally within a curtain wall between two consecutive bastions, this gate was situated on a flank of the Bastion of the Trinity, a design choice that was later criticized as one of the major mistakes in the defensive layout.

The width of the defensive wall at this location is approximately twelve meters. The passage beneath the wall is covered by a very wide barrel vault. The interior façade is relatively plain, adorned only with a pair of spiral-shaped figures, and the construction date: 1680. Additionally, it features a small postern—a secondary, often concealed door—intended for quick access to the moat and [rainwater drainage. Between 1930 and 1940, part of the bastion was demolished to facilitate road traffic, resulting in the loss of this historical element of the city.

- Gallery

-

Plaque with the legend "YEAR" (of its construction)

-

Plaque with the legend "1680" (year of construction)

-

Coat of arms of Charles II on the exterior facade

-

Stonemasons' marks on ashlars

-

Stonemasons' marks on ashlars

-

Exterior Facade

-

Gate of La Trinidad and southwest-facing curtain wall

-

Interior Facade

Pilar Gate

[edit]

Designated as number 12 on the Plan of Gates, it is located in the southwestern part of the defensive system, situated between the Bastions of San Roque and San Juan. It was constructed in 1692. Due to its exposure to enemy fire, the gate was protected by a glacis, and in front of it stood the "Fort of Pardaleras." The fort was connected to the gate by a covered road, which provided protection from enemy fire and allowed for the secure relief of troops, as well as the resupply of ammunition, food, and water.[49] Originally, the gate featured a drawbridge to facilitate crossing the moat surrounding the city. The openings for the lever systems used to raise the drawbridge on both sides of the gate are still preserved. This gate is the only one within the enclosure for which there is reliable evidence of having had a drawbridge.[50]

The exterior façade of the gate displays the coat of arms of the Count of Montijo, featuring rampant lions on either side. The Count, who was the Captain General of the province, oversaw the construction and completion of the gate in 1692. He also donated the small statue of Our Lady of the Pillar, which is located on the interior façade of the gate and from which it derives its name. The statue was ceremoniously moved from the cathedral in a procession led by the Bishop of Badajoz, Marín de Rodezno, and installed at the gate. The façade also features a statue of King Charles II. On either side of the exterior façade, two columns are believed to have served as pedestals for religious images.[51] Historically, the gate was known as Jerez Gate because the road from Badajoz through it led to Jerez, and later as Santa Marina Gate due to its proximity to the convent of the same name, associated with the Templars.[52]

Until the end of the 20th century, the gate was connected to the defensive walls by the Bastion of San Roque to the west and the Bastion of San Juan to the east. However, the Bastion of San Juan was demolished at the end of the 20th century to make way for road traffic, resulting in an irreparable loss of this historical element of the defensive enclosure.[50] It has two commemorative plaques on both sides of the inner side that were placed in the act of its inauguration and read as follows:

The fervent devotion of the Excelentisimo Lord Count of Montijo,... ordered to place in this door the Image of Our Lady of Pilar, ... to greater honor and glory of God and His Blessed Mother. year of 1692.[53]

Don Juan Marin de Rodezno Bishop of Badajoz granted forty days of indulgences ... of this border and province of Extremadura.[53]

The main feature of the Pilar Gate is its design as a vaulted gallery of substantial dimensions, accommodating the passage of carriages. It extends slightly beyond the width of the defensive wall and features façades adorned with semicircular arches and pediments on the cornices, topped by three spheres that retain their original Baroque style. Currently, the gate is surrounded by a park known as Parque de los Cañones. Visible traces of the grooves through which chains were run to operate the drawbridge can still be seen. This drawbridge was later replaced by a fixed bridge.[10][54] The gate is notable for preserving drawings and engravings on the columns of the exterior façade, created by the stonemasons and soldiers who once guarded it.[55] In the last third of the 20th century, the Pilar Gate underwent a restoration that was well-received by historians. The restoration preserved its original Baroque features, including the pediment and the royal coat of arms, as well as the grooves used for the drawbridge chains.[10]

- Gallery

-

Geometric decoration elaborated with sgraffito in the interior zone

-

Coats of arms on the exterior Facade

-

Marks of stonemasons

-

Niche with an image of the Virgen del Pilar

-

Marks of the soldiers on duty

-

Exterior Facade with drawbridge

Palmas Gate

[edit]

Designated as number 13 on the Plan of Gates, it is situated in front of the Palmas Bridge, also known as the Old Bridge, and is located in the Plaza de los Reyes Católicos. Constructed around 1460, it originally connected the historic center of Badajoz with the Old Bridge over the Guadiana River. Although the gate still serves this function, it is now isolated as a historical architectural element, with the connection to the bridge maintained via two side streets that surround it. Initially called "Puerta Nueva" (New Gate), it was renamed Palmas Gate following the construction of another gate in the 17th century in front of what is now the Autonomy Bridge. The gate features two distinct façades—interior and exterior.[56]

The interior façade is flanked by two cylindrical merlon towers of circular section. These towers are joined by a lower body or access opening, which connects the two towers through a segmental arch with a slight archivolt. The towers are topped with a decorative stone cordon, typical of the 16th century, below the battlements. At the height of their terraces, the towers feature acroteria or plinths supporting ornaments. The upper body of the gate is distinguished by three successive semicircular arches spanning from one tower to the other. The central arch is the largest, flaring slightly inward, and is decorated with coffers. At its center is an image of "Our Lady of the Angels", sculpted by Guillermo Silveira on the order of the architect Francisco Vaca Morales. This image is housed in a Renaissance niche with a segmental arch and a somewhat lowered pediment, flanked by two carved angels in relief. A terrace or chemin de ronde in front of these arches connects both towers.[57][58]

The exterior façade features two concentric semicircular arches. The interior surface of the outer arch is adorned with geometric coffered decorations. The spandrels of the outer arch display medallions of Charles V and Philip II. An inscription at the top of this façade indicates that the gate was built in 1551 during the reign of Philip II.[59]

In addition to its defensive and passage control functions, the Palmas Gate also serves a symbolic role akin to a triumphal arch, honoring the sovereigns and kings of its time. Designed in the Renaissance style, it emulates the triumphal arches of Roman civilization. At the beginning of the 19th century, the gate was used as a prison. It was restored in 1960 by Francisco Vaca Morales, an architect, writer, essayist, and art critic. The Palmas Bridge, the oldest bridge crossing the Guadiana River in Badajoz, is closely associated with the Palmas Gate. It was constructed in 1596 during the reign of Philip II, with Diego Hurtado de Mendoza serving as governor of Badajoz. The bridge bears an inscription marking its completion in 1596. However, some historians suggest that the bridge may have been built concurrently with the gate in 1460 and was later destroyed by a major flood in 1545.[60]

- Gallery

-

Detail of chord, windows, and gables

-

Inner arch with coffers

-

East tower with windows and chord

-

Coat of arms of Charles V on the exterior facade

-

Detail of the stone chord at the base of the towers

-

Virgin of the Angels on the inner facade of Palmas Gate

Pajaritos Gate

[edit]

It has the number 14 in the Plan of Gates. It is located under a tower in which is located the Hermitage of Pajaritos, although the exact date of its construction is not known, certain historians like Ayala and Rubio are inclined by the thesis that it could be of Islamic origin and indicate that it was of angled axis, that is to say, not straight, to make difficult the passage to the enemy and that it was not demolished when the Vauban defensive wall was raised.[61] Other historians indicate that it was built in the 16th century.[62]

For a significant period, the gate was closed to both vehicles and pedestrians and was even used as a sewer. It is currently walled up. During the construction of the Vauban defensive wall, the gate was preserved and framed at both ends with brick arches. The base of the vault is supported by granite ashlars along the entire length of the gate. A small passageway provided access to an outbuilding likely intended for the gate's guard personnel. Although it is now semi-buried, it was originally situated at a higher level relative to the surrounding area to fulfill its function as a gate.[62]

The gate is located near the "Bridge of Autonomy", adjacent to a traffic circle featuring sculptures of the heads of Luis Alvarez Lencero, Jesus Delgado Valhondo, and Manuel Pacheco, all poets from Extremadura. These sculptures were created by the Badajoz sculptor Luis Martínez Giraldo.[63]

Adjacent to the gate is the Hermitage of Pajaritos, also known as the Hermitage of the Orioles. The exact date of its initial construction is unknown. Local tradition suggests that the gate's name derives from a painting by Luis de Morales called "La Virgen del Pajarito", dated 1546, which was once displayed at the gate and is now preserved in the Church of San Agustín in Madrid.[61] However, it appears that the gate originally featured a carving of the Virgin and Child, which is now located in the Church of San Agustín in Badajoz.[64]

- Gallery

-

Area of the defensive wall next to where the gate used to be

-

South-eastern view and view of the east defensive wall start

-

Western view of the hermitage

-

Curtain wall of the defensive wall where the Pajaritos Gate used to be

-

Decorative detail on the defensive wall in that area

-

Hermitage of Pajaritos. South-eastern view and start of defensive walls

San Vicente Gate

[edit]

Designated as number 15 on the Plan of Gates, San Vicente Gate is uniquely situated outside the bastioned enclosure of Badajoz, on the right bank of the Guadiana River. It is located at the northern end of the Palmas Bridge, to the east of the "Hornabeque del Puente de Palmas", near the bridge's exit.[65]

Built around 1665, San Vicente Gate served as one of the primary access points to the city for over two centuries. It was strategically important as it provided entry to Badajoz after crossing the Palmas Bridge, which spans the Guadiana River. A covered way originating from the gate extended to the Fort of San Cristóbal, situated on a hill that commands the right bank of the river, overlooking the old city of Badajoz.[65]

The gate features a semi-elliptical opening that extends into an interior passageway with a barrel vaulted ceiling. Above the gate, a bartizan is mounted on cantilevers and includes an arrowslit floor, allowing defenders to observe and protect the entrance without exposing themselves to enemy fire. This bartizan is uniquely square in section, distinguishing it from other geometric forms within Badajoz's bastioned defensive system, and includes a terrace for access.[66]

A room within the gate housed the guard responsible for managing its access, including opening it in the morning and closing it in the evening. Beneath the hornwork, there is a moat crossed by a small bridge supported by two square columns, each crowned with a ball. Both the bridge and columns are constructed of masonry. The gate ceased to function when the deck of Palmas Bridge was extended over the hornwork at the end of the 19th century.[67]

Pelambres Gate

[edit]

Numbered 16 on the Plan of Gates, Pelambres Gate, also known as "Portillo de Pelambres", is first documented in the early 16th century. Its name derives from the tanners' guild located nearby, which used the gate to evacuate waste from the "Curtidores" neighborhood. The gate was originally situated opposite the old "Street of the River", which later became known as "Street of Joaquín Sama."[45] It is positioned between Palmas Gate and New Gate.[68]

Historical maps and engravings indicate that Pelambres Gate was constructed between two relatively small towers or possibly within a larger tower that remained standing until the late 18th century. Its function extended beyond providing access to the river; it also served as a conduit to the nearby "Fuente de Mafra." With the opening of the New Gate (also known as Chariots Gate) and Palmas Gate, both located nearby, Pelambres Gate lost its primary function and was repurposed as a sewer or spillway. By 1886, when the "Batería del Redondo" was connected to the "Puerta de Palmas" by a defensive wall, the gate was completely closed. It was filled with earth and stones on the interior side to elevate the surrounding street and enhance the area's defensive position. Today, only remnants of the spillway's lintel are visible on the outer face of the defensive wall at ground level.[69]

New Gate

[edit]

Number 17 on the Plan of Gates, the New Gate is situated opposite the current Autonomy Bridge and behind the former palace of Godoy, which has served as a prison in the past and is now the School of Business Sciences. The gate is located in a curtain wall of the defensive structure that extended from Pajaritos Gate to Pelambres Gate. Following the construction of the New Gate, both Pelambres Gate and Pajaritos Gate were closed to traffic. The New Gate featured a double doorway with a front drum and included a space for the guard corps.[70][71]

Construction of the New Gate began at the end of the 17th century under the design of the military engineer Martín de Gabriel and was completed in 1765. It was also known as Chariots Gate or Gate of the River, though these names were also applied to other gates in the walled enclosure facing the Guadiana River. The New Gate shared similar characteristics with the Pilar Gate; although the New Gate was demolished in 1962, photographs and descriptions reveal that it featured a segmental arch flanked by columns and topped with a cornice. Like the Pilar Gate, it included a guardhouse and an access ramp.[72] At the beginning of the 21st century, the gate's buried foundations were discovered, having been obscured since its closure and subsequent demolition.[73]

Forts

[edit]Fort of San Cristóbal

[edit]

The Fort of San Cristóbal is situated on the right bank of the Guadiana River, atop the "Cerro de San Cristóbal", which is encircled by the EX-100 road. Access to the site is via a recently paved dirt road from the intersection of Inés Medrano Gil and Cardenal Cisneros streets. Initially owned by the Ministry of Defense, the fort was acquired by the Badajoz City Council in 1973.[74]

The Fort of San Cristóbal is the only surviving example of the outer defensive forts of Badajoz, preserved in its original form. The site where the fort stands, Cerro de San Cristóbal, was once the location of the Dukes of Orinaza's palace, and Ibn Marwan planned to establish the city of Badajoz there in the 9th century.[75]

Constructed during the Portuguese Restoration War, the fort was among the first to enhance Badajoz's medieval defensive system. Construction began in 1642. It is the sole exterior fort of the numerous ones built that remains intact. The fort is rectangular, featuring two small bastions and two semi-bastions. The section of the defensive wall connecting the two northern bastions is protected by a ravelin. The southern semi-bastions are linked by an embrasured gorge, a narrowing in the triangular portion of the ravelin where it meets the defensive wall.[76][77]

The Fort of San Cristóbal was equipped with embrasures for twelve cannons and could accommodate approximately 300 riflemen. Its defensive walls are surrounded by a moat lined with stone from a nearby quarry. Above this moat are an additional defensive wall and a "paseo de ronda" (walkway for patrols).[78] During its reconstruction, the original defensive walls were reinforced with stone and fitted with five outer crescents that served as advanced defenses. These were strategically placed along the northern flank, which lacked natural protection from the river. Repair work continued throughout the war, integrating the new construction with the old medieval walls. A covered way connected the fort's gate with the San Vicente Gate in the Hornabeque del Puente de Palmas, and some sections of this covered way have been preserved.[79]

The vicinity of the fort was the site of the Battle of the Gebora on February 19, 1811. This battle, which resulted in a French victory over the Spanish army, is commemorated on the Arc de Triomphe of Paris, with the names of both Badajoz and Gévora inscribed to honor the battles fought there.[80] The fort currently houses the Interpretation Center of the Fortifications of the Border. In January 2014, restoration work and tourist management of the fort were undertaken by a private company.[81]

Fort of the Prince or the Picuriña

[edit]The fort is located in the southeastern part of the city, within the "Park of the Picuriña", adjacent to Marqués de Lombay Street. This fort was part of the outer defenses of the Badajoz bastioned enclosure, situated northeast of the Bastion of Trinidad, between the San Miguel mountain range and the Rivillas stream. Today, only a few structures remain in a semi-ruinous state.[82]

Constructed in 1705, the fort was maintained until the 1970s, when most of it was demolished, leaving only a few buildings standing. Despite its relatively small size, the fort was a formidable defensive structure, separate from the city's bastioned enclosure. It was surrounded by a moat, with access to the interior provided by a drawbridge. Communication with Badajoz was facilitated by a covered way. The interior space, serving as a parade ground, was triangular in shape. The perimeter defensive wall featured twenty embrasures, highlighting its defensive capabilities. Additionally, bartizans were positioned at the corners of the perimeter, and the lower part of the wall included embrasures designed to accommodate firearms and artillery to protect the moat in the event of an enemy assault.[83]

Fort of Pardaleras

[edit]

The fort was one of the walled redoubts that comprised the outer defenses of the bastioned enclosure. Its strategic location allowed it to effectively cover the Calamón stream, as well as the hills of Picuriña and the Wind, with artillery fire. The Picuriña hill, though not very high, held significant strategic value and was highly sought after by besiegers, leading to frequent attacks from this area. The fort was situated directly across from the Pilar Gate. In the 20th century, the site was repurposed for the Preventive and Correctional Prison of Badajoz. Subsequently, the Ibero-American Museum of Contemporary Art was established on the site, which retains the characteristic cylindrical building of the former prison. It is noteworthy that the photographs referenced in the description of the Pardaleras fort depict the Picuriña fort.[49]

Fort of Las Cuestas

[edit]In the northwest area of Badajoz, outside the city limits, was the "Bastioned Fort of Las Cuestas", also known as the line of fortification of Las Cuestas. Situated north of the Santa Engracia neighborhood, the fortification bordered the right bank of the Cuestas stream in an area known as "Cuesta Colorada." Its perimeter extended from the BA-020 road, which connects to the Portuguese city of Campo Maior, to a drinking water treatment station at the opposite end. The fortification was a significant defensive structure, frequently targeted by the Portuguese army during their advances towards Badajoz. After its operational period, the fort was completely razed, leaving no preserved remains. The fort of Las Cuestas, located centrally within this defensive line, featured a pentagonal plan with bastions and semi-bastions at its corners. Today, only aerial views reveal the remnants of three forts and approximately 500 meters of trenches.[84]

Hornwork of the Head of the Palmas Bridge

[edit]

The hornwork is a critical component of the defensive architecture of Badajoz, designed as an external fortification to bolster the city's defenses, particularly for controlling and protecting river crossings. This particular hornwork is situated on the right bank of the Guadiana River, adjacent to the north end of the Palmas Bridge. Construction began in 1642, coinciding with the establishment of the city's modern defensive system.[85]

The "Head of the Bridge" was protected by a hornwork of this type and is composed of two semi-bastions joined by a curtain wall between them. The exit to the exterior was made going down the ramp that descends to the San Vicente Gate, not existing then the last arches of the bridge, which are of modern construction. It has a moat, a troop training square, crossings, foothills, a room for the guard corps, and a room for the chief officer of the troops, as well as three bartizan and several embrasures for cannons.[86]

The hornwork has a single gate on its right flank, the San Vicente Gate, from where the roads to Alburquerque, Elvas, the Portuguese city of Campo Maior, and the covered road that led to the fort of San Cristóbal used to leave. There are also some remains of the Rana fountain, built in the 18th century in the vicinity. The Palmas Bridge over the hornwork was built in 1868, lengthening the deck to give continuity to the bridge towards the street that linked the city with the new railroad station and thus facilitate the passage of vehicles.[85]

The forts of Cabeza del Puente and San Cristóbal played a crucial role in the conflict between Spain and Portugal, enduring numerous attacks and sieges. Notably, on June 23, 1658, during a protracted night assault, Portuguese forces managed to capture the fort. However, it was subsequently reclaimed by the "Third of the Armada" at the cost of significant casualties, including several captains and the Marquis of Lanzarote, who was the governor of Badajoz. Despite this setback, the Portuguese forces regrouped at "Vado del Moro", fortified the area, and laid siege to the city once more.[86]

The route through the fortifications, marked by numerous galleries and moats, is complex and challenging to navigate. It extends from the west flank to the east and then returns in the opposite direction, with various deviations as previously described.

- Gallery

-

View from the outside of the west flank

-

View from the outside of the west flank

-

Acute-angled west flank curtain walls, moat, and bartizan

-

Westerly angled curtain walls, bartizan, and moat

-

Curtain walls at a very acute angle, moat, and bartizan and Palmas Bridge in the background

-

Northwestern curtain wall of the defensive wall with bartizan and embrasures

-

Badajoz hornwork project by Lorenzo Possi, ca. 1665

-

Modern crossing of the Palmas Bridge through the hornwork

-

Three angled curtain walls, bartizan, moat, and embrasures to the northwest

-

West half with angled curtain walls, bartizan, moat, and embrasures

-

Palmas Bridge from the hornwork that is divided in two by the bridge

-

Eastern flank with bartizan, moat, and San Vicente Gate

-

Exit from the San Vicente Gate to the covered road to the fort of San Critóbal

-

Eastern flank from Palmas Bridge and San Vicente Gate

-

Night view of the right flank, to the north

-

Figurative scheme of the hornwork

Minor forts

[edit]In addition to the bastioned enclosure and the outer forts, a series of outer forts with less defensive capacity were also built, since they were defended only by moats and stakes. Erected in haste, very few had "covered passages", that is to say, communications by means of long trenches with sufficient depth to be protected from enemy fire when passing through them. In several cases, the defenders were surrounded by the enemy, who took the fort and used it to tighten the siege. Among the various forts that were built were those of "Las Mayas", "Cerro del viento", "Vado del Mayordomo", "Vado del Moro", "San Miguel", "San Gabriel", "San Gaspar", "Telena" and several others.[87]

Ravelines

[edit]

The ravelin, also known as rebellín in old Spanish, is a generally triangular fortification located exempt from the body of the main fortification and in front of it, usually on the other side of a moat to divide the attacking force and better cover the curtain walls by means of crossfire. Together with other elements, it is part of the so-called bastion fort, hence its etymology, since it comes from the Italian rivellino or revellino. Riflemen stand on benches that allow them to fire while their comrades crouch down to charge without exposing themselves to enemy fire. The side of the triangle semi-parallel to the curtain wall where the ravelin is arranged does not usually have defenses so that, in case it is taken by the enemy, they cannot chemin de ronde and make themselves strong in it.[88]

Ravelin of San Roque

[edit]The ravelin of San Roque is situated between Ricardo Carapeto Avenue and the Rivillas stream. Constructed in the late 18th century, it served to defend the Puerta del Pilar and was connected by a covered road to the Fort of La Picuriña. The area between this ravelin and the rest of the fortifications could be inundated; therefore, during the siege of 1812, a dam was built downstream of the Rivillas stream to raise its water level by several meters. The primary role of the ravelin was to protect the zone between the Bastion of San Pedro and the Bastion of La Trinidad.[89]

The ravelin features a nearly equilateral triangular floor plan, with the base oriented towards the bastioned enclosure and the apex facing outward. The base was left unprotected to prevent it from being used as a defensive position by attackers if captured. This design also allowed for the retreat of defending forces into the city if the ravelin fell to the enemy. The height of the ravelin was intentionally lower than that of the city’s defensive walls, to avoid providing a vantage point for attackers. It included a covered embankment and parapet. In the early 21st century, the ravelin underwent numerous modifications, although many of its original features have been preserved. The area nearest to the Rivillas stream has been developed into a park, allowing some of the ravelin’s original elements to be visible. However, the opposite area is now obscured by modern buildings, which have largely concealed the ravelin.[90]

Ravelin of the Auditorium

[edit]

The ravelin of the Auditorium, named for its proximity to the Ricardo Carapeto Municipal Auditorium, is situated between the bastions of San José and San Vicente. Its primary defensive role was to protect the curtain wall connecting these two bastions. The ravelin features a low, triangular plan, with the point of the triangle directed outward, towards potential attacking forces. This design aimed to channel and divide enemy forces, thereby enhancing the defense of the adjacent bastions. The bastion of San Vicente has a postern on its left flank, protected by an orillon, as in other bastions already mentioned. This postern facilitated communication between the ravelin and the interior of the city, and it remains extant, providing a connection between the upper part of the bastion of San Vicente and the area of the ravelin. The nearby Ricardo Carapeto Municipal Auditorium, which gives the ravelin its popular name, is situated adjacent to this fortification.[91]

Ravelin of the Fort of San Cristóbal

[edit]The ravelin situated within the Fort of San Cristóbal has a triangular layout, with one vertex directed outward, specifically towards the northwest. This orientation was designed to face potential attacks from the Portuguese army, which approached from that direction.[91]

Complex of tunnels and subway tunnels of the bastioned system

[edit]During the construction of the semi-bastion of San Antonio, which was part of the bastioned defensive wall system, and the closure of the Alpendiz Gate, a series of tunnels and subterranean chambers were constructed in that area in the 17th century. These structures, known as the "Subterráneos de Calatrava" (Calatrava's Subterraneans), were utilized for housing troops and storing military supplies, benefiting from their robust walls and bomb-proof vaults.[92]

Moats

[edit]

In the bastioned enclosure of Badajoz, moats encircled the entire perimeter as well as external fortifications such as forts and ravelins. In certain instances, the moats were lined with masonry, creating a counterscarp that was integrated with the defensive wall. At specific locations, such as around the Bastion of La Trinidad and the ravelin of San Roque, the moats could be flooded to enhance their defensive capacity.[93]

Today, moats are still visible around nearly all preserved sections of the defensive wall in Badajoz. However, the counterscarp is preserved only around the bastions of San Pedro and Santa María, as well as in the hornwork, the fort of San Cristóbal, and the ravelins of San Roque and Auditorio.[94]

The riflemen's galleries

[edit]An embrasured gallery for riflemen is a defensive gallery located inside a bastion, typically positioned on its flanks. This gallery features small arrowslits and is divided into cells by transverse partitions, allowing soldiers to fire and cover the moat. The gallery includes thick partition walls separating every three riflemen's posts, ensuring that an artillery hit in one area would not compromise adjacent areas. In the bastioned enclosure of Badajoz, riflemen's galleries were constructed in the late 18th century based on designs by the engineer Pedro Ruiz de Olano. Today, all but one of these galleries have been preserved.[40]

Covered roads, traverses, parade grounds, and foothills

[edit]

The covertway way bordered all the moats and provided communication between the city and the forts and outer ravelins. Its primary function was to facilitate the movement of troops while shielding them from enemy fire and to enable them to fire from within the covered way while protected by the parapet. The covered ways were concealed behind a series of foothills.[95]

Squares of arms, which served as open spaces for troop assembly and maneuver, were present in several bastions, in the vicinity of the ravelin of San Roque, the Auditorium, and in the hornwork of the Head of the Bridge. Traverses, together with stakes, were used to protect the parade grounds. In Badajoz, traverses were located at the ends of parade grounds, in the hornwork of the Head of the Bridge, and along the covered road extending from the bridge of La Trinidad to the Merida Gate.[86]

Today, most of the covered ways have disappeared, although remnants can still be seen in several locations: from the bridge of La Trinidad to the Merida Gate, in the fort of San Cristóbal, in the hornwork of the Palmas Bridge, around the ravelin of San Roque, in front of the bastion of San Vicente, in the ravelin of the Auditorium, and around the moat encircling the Bastion of Santa María. The foothills that were located in front of nearly all the bastions have been removed, as these relatively flat areas have been repurposed for modern city construction.[96]

Mines, countermines, and listening wells

[edit]To prevent the effects of mining, counter-mines were constructed by digging subterranean galleries from within the fortifications, which were then equipped with powder magazines. In 1811, during the French occupation of Badajoz, the initial actions included the excavation of counter-mines between the Bastions of Santiago and San Vicente. Evidence suggests that several counter-mines were built in Badajoz, with one possible entrance located in the moat of the ravelin of Trinidad or San Roque.[97]

Additionally, a listening well has been identified in the fortifications of Badajoz, situated at an angle flanking the Bastion of La Trinidad. This structure consists of a passageway that descends from the chemin de ronde to the entrance of a chamber used as a listening well. It featured steps attached to the wall for access to the lower levels and has been tentatively dated to the 1770s. It is also possible that some small storehouses or gunpowder magazines may have served as listening wells at various times.[98]

The longest walled enclosure in Spain and the largest citadel in Europe and the world