Base erosion and profit shifting

| Part of a series on |

| Taxation |

|---|

|

| An aspect of fiscal policy |

Base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) refers to corporate tax planning strategies used by multinationals to "shift" profits from higher-tax jurisdictions to lower-tax jurisdictions or no-tax locations where there is little or no economic activity, thus "eroding" the "tax-base" of the higher-tax jurisdictions using deductible payments such as interest or royalties.[5][6] For the government, the tax base is a company's income or profit. Tax is levied as a percentage on this income/profit. When that income / profit is transferred to a tax haven, the tax base is eroded and the company does not pay taxes to the country that is generating the income. As a result, tax revenues are reduced and the country is disadvantaged. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) define BEPS strategies as "exploiting gaps and mismatches in tax rules".[6] While some of the tactics are illegal, the majority are not. Because businesses that operate across borders can utilize BEPS to obtain a competitive edge over domestic businesses, it affects the righteousness and integrity of tax systems. Furthermore, it lessens deliberate compliance, when taxpayers notice multinationals legally avoiding corporate income taxes. Because developing nations rely more heavily on corporate income tax, they are disproportionately affected by BEPS.[7]

Corporate tax havens offer BEPS tools to "shift" profits to the haven, and additional BEPS tools to avoid paying taxes within the haven (e.g. Ireland's "CAIA tool").[a] BEPS activities cost nations 100-240 billion dollars in lost revenue each year, which is 4-10 percent of worldwide corporate income tax collection. It is alleged that BEPS tools are associated mostly with American technology and life science multinationals.[b][2] A few studies showed that use of the BEPS tools by American multinationals maximized long–term American Treasury revenue and shareholder return, at the expense of other countries.[3][4][2]

Scale

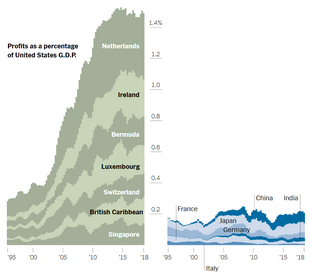

[edit]In January 2017 the OECD estimated that BEPS tools are responsible for tax losses of circa $100–240 billion per annum.[8] In June 2018 an investigation by tax academic Gabriel Zucman (et alia),[9] estimated that the figure is closer to $200 billion per annum.[10] The Tax Justice Network estimated that profits of $660 billion were "shifted" in 2015 due to Apple's Q1 2015 leprechaun economics restructuring, the largest individual BEPS transaction in history.[11][12][13] The effect of BEPS tools is most felt in developing economies, who are denied the tax revenues needed to build infrastructure.[14][15]

Most BEPS activity is associated with industries with intellectual property ("IP"), namely Technology (e.g. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Oracle), and Life Sciences (e.g. Allergan, Medtronic, Pfizer and Merck & Co) (see here) as our economy is changing to become more digital and knowledge based.[b][16] IP is described as the raw materials of tax avoidance, and IP–based BEPS tools are responsible for the largest global BEPS income flows.[17][18] Intangible assets such as patents, designs, trademarks (or brands) and copyrights are usually easy to identify, value and transfer, which is why they are attractive in tax planning structures for multinational companies, especially since these rights are not generally geographically bound and are therefore highly mobile. As a result, they can be relocated without significant costs using planned licensing structures. Several multinational companies use IP structuring models to separate the ownership, funding, maintenance and use rights of intangible assets from the actual activities and physical location of intangible assets to operate in a manner that the income made from the intangibles in one location is received in another location with a low/no tax regime. As such IP models have a meaningful role in the taxation of multinationals. Multinationals, for instance can establish licensing and patent holding companies suitable for offshore locations to acquire, exploit, license or sublicense IP rights for their foreign subsidiaries. Then profits can be shifted from the foreign subsidiary to the offshore patent owning company where low to no taxes are applied on the royalties earned. Any fees derived by the licensing and patent holding company from the exploitation of the intellectual property will be exempt from the tax or subject to a low tax rate in the tax haven jurisdiction, these companies can also be used to avoid high withholding taxes that are normally charged on royalties coming from the country in which they are derived, furthermore they can be reduced by double taxation treaties between countries. Many countries allow for the deductions in respect of expenditure on research and development (R&D) or on the acquisition of IP. As such MNE's can set up R&D facilities in countries where the best tax advantage can be obtained. As such MNEs can make use of an attractive research infrastructure and generous R&D tax incentives in one country and benefit in another from low tax rates on the income from exploiting intangible assets.

IP tax planning models such as these successfully result in profit shifting which in most instances may lead to base erosion of the tax base. Corporate tax havens have some of the most advanced IP tax legislation in their statute books.[19]

Intra group debts are another common way multinationals avoid taxes. Intra-group debts are particularly simple to use, as they do not involve third parties and "can be created with the wave of a pen or keystroke".[20] They often do not require any movement of assets, functions or personnel within a corporate group, nor any major change of its operations. Furthermore, intra-group debts provide significant flexibility for manipulations, as explained in a paper released by the United Nations.[21] The popularity of using intra-group debts as a tax avoidance tool is further enhanced by the fact that in general they are not recognized under accounting standards and therefore do not affect consolidated financial statements of MNEs. It is not surprising that the OECD describes the BEPS risks arising from intra-group debt as the "main tax policy concerns surrounding interest deductions" (emphasis added).[22]

Most BEPS activity is also most associated with U.S. multinationals,[23][24][5][16] and is attributed to the historical U.S. "worldwide" corporate taxation system.[5][25] Before the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), the U.S. was one of only eight jurisdictions to operate a "worldwide" tax system.[26] Most global jurisdictions operate a "territorial" corporate tax system with lower tax rates for foreign sourced income, thus avoiding the need to "shift" profits (i.e. IP can be charged directly from the home country at preferential rates and/or terms; post the 2017 TCJA, this happens in the U.S. via the FDII-regime).[27][28][29]

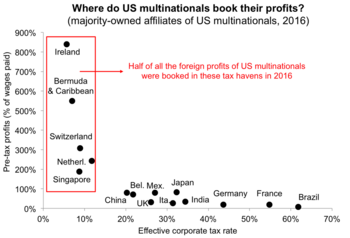

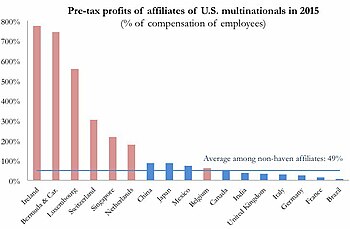

U.S. multinationals use tax havens[c] more than multinationals from other countries which have kept their controlled foreign corporations regulations. No other non–haven OECD country records as high a share of foreign profits booked in tax havens as the United States. [...] This suggests that half of all the global profits shifted to tax havens, are shifted by U.S. multinationals. By contrast, about 25% accrues to E.U. countries, 10% to the rest of the OECD, and 15% to developing countries (Tørsløv et al., 2018).

— Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Wright, "THE EXORBITANT TAX PRIVILEGE", NBER Working Papers (September 2018).[2]

Research in June 2018 identified Ireland as the world's largest BEPS hub.[30] Ireland is larger than the aggregate Caribbean tax haven BEPS system, excluding Bermuda.[31] The largest global BEPS hubs, from the Zucman–Tørsløv–Wier table below, are synonymous with the top 10 global tax havens:

|

(†) Mostly consists of The Cayman Islands and The British Virgin Islands

Research in September 2018, by the National Bureau of Economic Research, using repatriation tax data from the TCJA, said that: "In recent years, about half of the foreign profits of U.S. multinationals have been booked in tax haven affiliates, most prominently in Ireland (18%), Switzerland, and Bermuda plus Caribbean tax havens (8%–9% each).[2] One of the authors of this research was also quoted as saying, "Ireland solidifies its position as the #1 tax haven.... U.S. firms book more profits in Ireland than in China, Japan, Germany, France & Mexico combined. Irish tax rate: 5.7%."[citation needed]

Tools

[edit]Research identifies three main BEPS techniques used for "shifting" profits to a corporate tax haven via OECD–compliant BEPS tools:[33][34]

- IP–based BEPS tools,[d] which enable the profits to be extracted via the cross–border charge–out of internal virtual IP assets (known as "intergroup IP charging"); and/or

- Debt–based BEPS tools, which enable the profits to be extracted via the cross–border charge–out artificially high interest (known as "earnings stripping"); and/or

- TP–based BEPS tools,[d] shifts profits to the haven by asserting that a process performed in the haven (e.g., contract manufacturing), justifies a large increase in the transfer price ("TP") at which the finished product is charged–out by the haven to higher–tax jurisdictions.

BEPS tools could not function if the corporate tax haven did not have a network of bilateral tax treaties that accept the haven's BEPS tools, which "shift" the profits to the haven. Modern corporate tax havens, which are the main global BEPS hubs, have extensive networks of bilateral tax treaties.[35] The U.K. is the leader with over 122, followed by the Netherlands with over 100.[36][37] The "blacklisting" of a corporate tax haven is a serious event, which is why major BEPS hubs are OECD-compliant. Ireland was the first major corporate tax haven to be "blacklisted" by a G20 economy: Brazil in September 2016.[38][39]

An important academic study in July 2017 published in Nature, "Conduit and Sink OFCs", showed that the pressure to maintain OECD–compliance had split corporate–focused tax havens into two different classifications: Sink OFCs, which act as the terminus for BEPS flows, and Conduit OFCs, which act as the conduit for flows from higher–tax locations to the Sink OFCs. It was noted that the five major Conduit OFCs, namely, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Singapore and Switzerland, all have a top–ten ranking in the 2018 Global Innovation Property Centre (GIPC) IP Index".[19]

Once profits are "shifted" to the corporate tax haven (or Conduit OFC), additional tools are used to avoid paying headline tax rates in the haven. Some of the tools are OECD–compliant (e.g. patent boxes, Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets ("CAIA") or "Green Jersey"), others became OECD–proscribed (e.g. Double Irish and Dutch Double–Dipping), while others have not attracted OECD attention (e.g. Single Malt).

Because BEPS hubs (or Conduit OFCs) need extensive bilateral tax treaties (e.g. so that their BEPS tools will be accepted by the higher–tax locations), they go to great lengths to obscure the fact that effective tax rates paid by multinationals in their jurisdiction are close to zero percent, rather than the headline corporate tax rate of the haven (see Table 1). Higher–tax jurisdictions do not enter into full bilateral tax treaties with obvious tax havens (e.g. the Cayman Islands, a major Sink OFC). That is achieved with financial secrecy laws, and by the avoidance of country–by–country reporting ("CbCr") or the need to file public accounts, by multinationals in the haven's jurisdiction. BEPS hubs (or Conduit OFCs) strongly deny they are corporate tax havens, and that their use of IP is as a tax avoidance tool.[40] They call themselves "knowledge economies".[41]

Make no mistake: the headline rate is not what triggers tax evasion and aggressive tax planning. That comes from schemes that facilitate profit shifting.

— Pierre Moscovici, EU Commissioner on Taxation, Financial Times, 11 March 2018[42]

The complex accounting tools, and the detailed tax legislation, that corporate tax havens require to become OECD–compliant BEPS hubs, requires both advanced international tax–law professional services firms, and a high degree of coordination with the State, who encode their BEPS tools into the State's statutory legislation.[43][44] Tax investigators call such jurisdictions "captured states",[45][46][47] and explain that most leading BEPS hubs started as established financial centres, where the necessary skills and State support for tax avoidance tools, already existed.[48][49]

Agendas

[edit]The BEPS tools used by tax havens have been known and discussed for decades in Washington.[50] For example, when Ireland was pressured by the EU–OECD to close its double Irish BEPS tool, the largest in history, to new entrants in January 2015,[51] existing users, which include Google and Facebook, were given a five-year extension to 2020.[52] Even before 2015, Ireland had already publicly replaced the double Irish with two new BEPS tools: the single malt (as used by Microsoft and Allergan), and capital allowances for intangible assets ("CAIA"), also called the "Green Jersey", (as used by Apple in Q1 2015).[53][54] None of these new BEPS tools have been as yet proscribed by the OECD.[55] Tax experts show that disputes between higher-tax jurisdictions and tax havens are very rare.[56]

Tax experts describe a more complex picture of an implicit acceptance by Washington that U.S. multinationals could use BEPS tools on non–U.S. earnings to offset the very high U.S. 35% corporate tax rate from the historical U.S. "worldwide" corporate tax system (see source of contradictions).[57] Other tax experts, including a founder of academic tax haven research, James R. Hines Jr., note that U.S. multinational use of BEPS tools and corporate tax havens had actually increased the long–term tax receipts of the U.S. Treasury, at the expense of other higher–tax jurisdictions, making the U.S a major beneficiary of BEPS tools and corporate-tax havens.[3][4][58]

Lower foreign tax rates entail smaller credits for foreign taxes and greater ultimate U.S. tax collections (Hines and Rice, 1994).[59] Dyreng and Lindsey (2009),[4] offer evidence that U.S. firms with foreign affiliates in certain tax havens pay lower foreign taxes and higher U.S. taxes than do otherwise-similar large U.S. companies.

— James R. Hines Jr., "Treasure Islands" p. 107 (2010)[3]

The 1994 Hines–Rice paper[59] on U.S. multinational use of tax havens was the first to use the term profit shifting.[5] Hines–Rice concluded, "low foreign tax rates [from tax havens] ultimately enhance U.S. tax collections".[59] For example, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") levied 15.5% on the untaxed offshore cash reserves built up by U.S. multinationals with BEPS tools from 2004 to 2017. Had the U.S. multinationals not used BEPS tools and paid their full foreign taxes, their foreign tax credits would have removed most of their residual exposure to any U.S. tax liability, under the U.S. tax code.

The U.S. was one of the only major developed nations not to sign up to the 2016 § Failure of OECD (2012–2016) to curtail BEPS tools.[1]

Failure of OECD (2012–2016)

[edit]The 2012 G20 Los Cabos summit tasked the OECD to develop a BEPS Action Plan,[60][61] which 2013 G-20 St. Petersburg summit approved.[62] The project is intended to prevent multinationals from shifting profits from higher- to lower-tax jurisdictions.[63] An OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument, consisting of 15 Actions designed to be implemented domestically and through bilateral tax treaty provisions, were agreed at the 2015 G20 Antalya summit.

The OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument ("MLI"), was adopted on 24 November 2016 and has since been signed by over 78 jurisdictions. It came into force in July 2018. Many tax havens opted out from several of the Actions, including Action 12 (Disclosure of aggressive tax planning), which was considered onerous by corporations who use BEPS tools.

Global legal firm Baker McKenzie,[65] representing a coalition of 24 multinational US software firms, including Microsoft, lobbied Michael Noonan, as [Irish] minister for finance, to resist the [OECD MLI] proposals in January 2017. In a letter to him the group recommended Ireland not adopt article 12, as the changes "will have effects lasting decades" and could "hamper global investment and growth due to uncertainty around taxation". The letter said that "keeping the current standard will make Ireland a more attractive location for a regional headquarters by reducing the level of uncertainty in the tax relationship with Ireland's trading partners".

— Irish Times. "Ireland resists closing corporation tax ‘loophole’" (10 November 2017)[66]

The acknowledged architect of the largest ever global corporate BEPS tools (e.g. Google and Facebooks' Double Irish and Apple's Green Jersey), tax partner Feargal O'Rourke from PriceWaterhouseCoopers ("PwC), predicted in May 2015 that the OECD's MLI would be a success for the leading corporate tax havens, at the expense of the smaller, less developed, traditional tax havens, whose BEPS tools were not sufficiently robust.[67]

In August 2016, the Tax Justice Network's Alex Cobham described the OECD's MLI as a failure due to the opt–outs and watering–down of individual BEPS Actions.[68] In December 2016, Cobham highlighted one of the key anti–BEPS Actions, full public country–by–country–reporting ("CbCr"), had been dropped due to lobbying by the U.S. multinationals.[69] Country–by–country reporting is the only way to observe the level of BEPS activity and OECD compliance in any country conclusively .

In June 2017, a U.S. Treasury official explained that the reason why U.S. refused to sign up to the OECD's MLI, or any of its Actions, was because: "the U.S. tax treaty network has a low degree of exposure to base erosion and profit shifting issues".[1][70]

Failure of TCJA (2017–2018)

[edit]

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") moved the U.S. from a "worldwide" corporate tax system to a hybrid[e] "territorial" tax system. The TCJA includes anti–BEPS tool regimes including the GILTI–tax and BEAT–tax regimes. It also contains its own BEPS tools, namely the FDII–tax regime.[f] The TCJA could represent a major change in Washington's tolerance of U.S. multinational use of BEPS tools. Tax experts in early 2018 forecast the demise of the two major U.S. corporate tax havens, Ireland and Singapore, in the expectation that U.S. multinationals would no longer need foreign BEPS tools.[71]

However, by mid–2018, U.S. multinationals had not repatriated any BEPS tools,[g] and the evidence is that they have increased exposure to corporate tax havens. In March–May 2018, Google committed to doubling its office space in Ireland,[72] while in June 2018 it was shown that Microsoft is preparing to execute Apple's Irish BEPS tool, the "Green Jersey" (see Irish experience post–TCJA).[73] In July 2018, an Irish tax expert Seamus Coffey, forecasted a potential boom in U.S. multinationals on–shoring their BEPS tools from the Caribbean to Ireland, and not to the U.S. as was expected after TCJA.[74]

In May 2018, it was shown that the TCJA contains technical issues that incentivise these actions.[75] For example, by accepting Irish tangible, and intangible, capital allowances in the GILTI calculation, Irish BEPS tools like the "Green Jersey" enable U.S. multinationals to achieve U.S. effective tax rates of 0–3% via the TCJA's foreign participation relief system.[76] There is debate as to whether they are drafting mistakes to be corrected or concessions to enable U.S. multinationals to reduce their effective corporate tax rates to circa 10% (the Trump administration's original target).[77]

In February 2019, Brad Setser from the Council on Foreign Relations (CoFR), wrote an article for The New York Times highlighting material issues with TCJA in terms of curtailing U.S. corporate use of major tax havens such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Singapore.[78]

Setser followed up his New York Times piece on the CoFR website with:

So, best I can tell, neither the OECD's base erosion and profit shifting work nor the U.S. [TCJA] tax reform, will end the ability of major U.S. companies to reduce their overall tax burden by aggressively shifting profits offshore (and paying between 0-3 percent on their offshore profits and then being taxed at the GILTI 10.5 percent rate net of any taxes paid abroad and the deduction for tangible assets abroad). The only good news, as I see it, is that the scale of profit shifting is now so big that it almost cannot be ignored—it is distorting the U.S. GDP numbers, not just the Irish numbers. And in my view, the current tax reform's failure to change the incentive to profit shift will eventually become so obvious that it will become clear that the reform itself needs to be reformed.

— Brad Setser, "Why the U.S. Tax Reform's International Provisions Need to Be Reformed", Council on Foreign Relations, (2019).[79]

OECD BEPS 2.0 (2019)(2021)

[edit]On 29 January 2019, the OECD released a policy note regarding new proposals to combat the BEPS activities of multinationals, which commentators labeled "BEPS 2.0".[80][81] In its press release, the OECD announced its proposals had the backing of the U.S., as well as China, Brazil, and India.[82]

Irish-based media highlighted a particular threat to Ireland as the world's largest BEPS hub, regarding proposals to move to a global system of taxation based on where the product is consumed or used, and not where its IP has been located.[82] The IIEA chief economist described the OECD proposal as "a move last week [that] may bring the day of reckoning closer".[83] The Head of Tax for PwC in Ireland said, "There's a limited number of [consumers] users in Ireland and [the proposal under consideration] would obviously benefit the much larger countries".[84]

As of 8 October 2021 OECD has stated a new Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalization of the Economy. The scope of pillar one is in-scope companies are the multinational enterprises (MNEs) with global turnover above 20 billion euros and profitability above 10% (i.e. profit before tax/revenue) calculated using an averaging mechanism with the turnover threshold to be reduced to 10 billion euros, contingent on successful implementation including of tax certainty on Amount A, with the relevant review beginning 7 years after the agreement comes into force, and the review being completed in no more than one year. Extractives and Regulated Financial Services are excluded. Tax base determination: The relevant measure of profit or loss of the in-scope MNE will be determined by reference to financial accounting income, with a small number of adjustments. Losses will be carried forward. Elimination of double taxation : Double taxation of profit allocated to market jurisdictions will be relieved using either the exemption or credit method. The entity (or entities) that will bear the tax liability will be drawn from those that earn residual profit.

Pillar Two Overall design

Pillar Two consists of:

• two interlocking domestic rules (together the Global anti-Base Erosion Rules (GloBE) rules): (i) an Income Inclusion Rule (IIR), which imposes top-up tax on a parent entity in respect of the low taxed income of a constituent entity; and (ii) an Undertaxed Payment Rule (UTPR), which denies deductions or requires an equivalent adjustment to the extent the low tax income of a constituent entity is not subject to tax under an IIR; and

• a treaty-based rule (the Subject to Tax Rule (STTR)) that allows source jurisdictions to impose limited source taxation on certain related party payments subject to tax below a minimum rate. The STTR will be creditable as a covered tax under the GloBE rules.

Scope The GloBE rules will apply to MNEs that meet the 750 million euros threshold as determined under BEPS Action 13 (country by country reporting). Countries are free to apply the IIR to MNEs headquartered in their country even if they do not meet the threshold. Government entities, international organisations, non-profit organisations, pension funds or investment funds that are Ultimate Parent Entities (UPE) of an MNE Group or any holding vehicles used by such entities, organisations or funds are not subject to the GloBE rules.

Minimum rate: The minimum tax rate used for purposes of the IIR and UTPR will be 15%.

Current efforts

[edit]OECD

[edit]In 2013 the OECD along with G20 has introduced its BEPS Project, which aims to give governments tools to prevent international companies from tax avoidance. The project consists of 15 Actions, which OECD advises governments to follow in order to prevent profit shifting. An example of such recommendation is avoidance of direct taxation on digital products. Furthermore, the project improves cooperation information sharing between countries.[85]

G20

[edit]The G20 along with OECD has been actively involved in the BEPS Project. In 2015, the G20 supported the transfer pricing recommendations, which aims to guide governments on how profits of multinational companies should be divided among individual countries.

Furthermore, the G20 is involved in developing a global tax framework. In 2021 the G20 endorsed a framework for international tax reforem, which provides guidance for implementation of the global minimum tax.[86]

EU

[edit]In 2016, the EU has adopted an Anti-Tax Avoidance Directive (ATAD), which follows the BEPS project and aims to implement its recommendations.[87]

In 2017 the EU introduced mandatory disclosure rules for tax planning intermediaries, demanding the intermediaries to report information to tax authorities, in order to aid identifying and addressing BEPS issues.[88]

The EU is also involved in forming an international tax framework, through which it aims to establish a global minimum tax rate for multinational companies.

The EU has signed multiple international tax treaties and has been working on their implementation in order to tackle the BEPS. Furthermore, the EU has been involved in discussions on the common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB) development, which reduces the opportunities for tax planning.[89]

UN

[edit]Through the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, the UN has been trying to combat BEPS. The Committee has been involved in developing the UN Model Tax Convention, which guides governments on rights of taxation and preventiontion of double taxation.[90]

Moreover, the UN has contributed in the efforts to develop the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) standard, which provides tax authorities with additional information about multinational companies, hence helping to identify BEPS issues.[91]

See also

[edit]- Tax haven

- Country-by-Country Reporting

- Conduit and Sink OFCs

- James R. Hines Jr.

- Helena Malikova

- Gabriel Zucman

- Ireland as a tax haven

- Transfer mispricing

- Global minimum corporate tax rate

Notes

[edit]- ^ The Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets (CAIA) BEPS tool, also known as the Green Jersey, was the BEPS tool Apple used in Q1 2015 to restructure its non-U.S. IP. It created the famous "leprechaun economics" event in Ireland in August 2016, when restated Irish GDP rose 34.4% in a single quarter

- ^ a b The critical component of the most important BEPS tools is intellectual property ("IP"), which the BEPS tool converts into a charge that is deductible against pre–tax income. Technology, Life Sciences, and industries have the largest pools of IP.

- ^ The paper lists tax havens as: Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda and Caribbean havens (page 6.)

- ^ a b Some academics consider IP–based BEPS tools to be a subset of TP–based BEPS tools (e.g. the corporate is transfer pricing the IP like any other product), however others consider IP to be a unique item (e.g. the IP is a virtual product whose value is decided internally by the corporation; it is more of an accounting invention rather than a tangible good), that it is a separate set.

- ^ The TCJA system is described as hybrid, because it still forces minimum U.S. tax rates on foreign income under the TCJA GILTI regime

- ^ The FDII regime allows U.S. multinationals to charge-out intellectual property ("IP") direct from the U.S., at a preferential 13.125% U.S. tax rate

- ^ This is not to be confused with the repatriation of the circa USD 1 trillion in offshore untaxed cash; these are the intellectual property ("IP") assets that U.S. multinationals house in locations like Ireland, which are the raw materials for the BEPS tools. A repatriation of a major U.S. multinational BEPS tool would cause reverse–leprechaun economics events in various tax havens

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Treasury Official Explains Why U.S. Didn't Sign OECD Super-Treaty". Bloomberg BNA. 8 June 2017. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

The U.S. didn't sign the groundbreaking tax treaty inked by 68 [later 70] countries in Paris June 7 [2017] because the U.S. tax treaty network has a low degree of exposure to base erosion and profit shifting issues", a U.S. Department of Treasury official said at a transfer pricing conference co–sponsored by Bloomberg BNA and Baker McKenzie in Washington

- ^ a b c d e f Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Wright (September 2018). "THE EXORBITANT TAX PRIVILEGE" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research: 11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d James R. Hines Jr. (2010). "Treasure Islands". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (24): 103–125.

Lower foreign tax rates entail smaller credits for foreign taxes and greater ultimate U.S. tax collections (Hines and Rice, 1994). Dyreng and Lindsey (2009), offer evidence that U.S. firms with foreign affiliates in certain tax havens pay lower foreign taxes and higher U.S. taxes than do otherwise-similar large U.S. companies

- ^ a b c d Scott Dyreng; Bradley P. Lindsey (12 October 2009). "Using Financial Accounting Data to Examine the Effect of Foreign Operations Located in Tax Havens and Other Countries on US Multinational Firms' Tax Rates". Journal of Accounting Research. 47 (5): 1283–1316. doi:10.1111/j.1475-679X.2009.00346.x.

Finally, we find that US firms with operations in some tax haven countries have higher federal tax rates on foreign income than other firms. This result suggests that in some cases, tax haven operations may increase US tax collections at the expense of foreign country tax collections.

- ^ a b c d Dhammika Dharmapala (2014). "What Do We Know About Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature". University of Chicago. p. 1.

It focuses particularly on the dominant approach within the economics literature on income shifting, which dates back to Hines and Rice (1994) and which we refer to as the "Hines–Rice" approach.

- ^ a b "OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting".

- ^ "About - OECD BEPS". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "BEPS Project Background Brief" (PDF). OECD. January 2017. p. 9.

With a conservatively estimated annual revenue loss of USD 100 to 240 billion, the stakes are high for governments around the world. The impact of BEPS on developing countries, as a percentage of tax revenues, is estimated to be even higher than in developed countries.

- ^ Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. p. 31.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

- ^ "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". The Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018.

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $200 billion globally

- ^ a b Brad Setser; Cole Frank (25 April 2018). "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ "Tax avoidance and evasion: The scale of the problem" (PDF). Tax Justice Network. 17 November 2017.

- ^ "The scale of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS): Tax Justice Network". Tax Justice Network.

- ^ "New UN tax handbook: Lower–income countries vs OECD BEPS failure". Tax Justice Network. 11 September 2017.

- ^ "The desperate inequality behind global tax dodging". The Guardian. 8 November 2017.

- ^ a b Alex Cobham (24 July 2018). "Progress on global profit shifting: no more hiding for jurisdictions that sell profit shifting at the expense of others". Tax Justice Network.

..for US multinationals, the real explosion in profit shifting began in the 1990s. At this point, a 'mere' 5–10% of global profits were declared away from the jurisdictions of the underlying real economic activity. By the early 2010s, that had soared to 25–30% of global profits, with an estimated revenue loss of around $130 billion a year..

- ^ Andrew Blair-Stanek (2015). "Intellectual Property Law Solutions to Tax Avoidance" (PDF). UCLA Law Review.

Intellectual property (IP) has become the leading tax-avoidance vehicle.

- ^ "Intellectual Property and Tax Avoidance in Ireland". Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal. 30 August 2016.

- ^ a b United States Chamber of Commerce (February 2018). "GIPC IP Index 2018" (PDF). p. 6.

Figure I: U.S. Chamber International IP Index 2018, Overall Scores

- ^ "A Brave New World", Goldilocks and the water bears, Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2018, doi:10.5040/9781472940902.0005, ISBN 978-1-4729-2011-9, retrieved 16 April 2022

- ^ "An exception whereby a third party may be given the right to enforce a term of a contract between two other parties where that term expressly or by implication is intended to benefit the third party. But, on the face of it, this merely relaxes the rules on privity of contract and not those relating to consideration. The answer to this problem seems to turn on the reasoning employed by the Law Commission, on whose report the provisions of the 1999 Act are based. The Law Commission expressed the view that the consideration question related only to the relationship between the original parties to the contract and should not apply also to the third party, since this would only raise questions of enforceability and would have no bearing on whether or not there was a bargain. Had the reasoning in the report stopped there, there would have been little difficulty. However, in a later section of the report, there are further views that the 1999 Act may have the effect of relaxing rules on consideration in certain respects. In particular, this view", Sourcebook on Contract Law, Routledge-Cavendish, p. 757, 12 December 1995, doi:10.4324/9781843141518-296, ISBN 978-1-84314-151-8, retrieved 16 April 2022

- ^ Limiting Base Erosion Involving Interest Deductions and Other Financial Payments, Action 4 - 2015 Final Report. 18 July 2016. doi:10.1787/9789264261594-ko. ISBN 9789264261594.

- ^ Richard Rubin (10 June 2018). "Corporations Push Profits Into Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Study Says". The Wall Street Journal.

U.S. companies are the most aggressive users of profit-shifting techniques, which often relocate paper profits without bringing jobs and wages, according to the study by economists Thomas Torslov and Ludvig Wier of the University of Copenhagen and Gabriel Zucman of the University of California, Berkeley

- ^ "New research finds 40% of multinationals' profits shifted to tax havens – EU biggest loser while US firms most shifty". Business Insider. 20 July 2018. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ James R. Hines Jr.; Anna Gumpert; Monika Schnitzer (2016). "Multinational Firms and Tax Havens". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 98 (4): 714.

Germany taxes only 5% of the active foreign business profits of its resident corporations. [..] Furthermore, German firms do not have incentives to structure their foreign operations in ways that avoid repatriating income. Therefore, the tax incentives for German firms to establish tax haven affiliates are likely to differ from those of U.S. firms and bear strong similarities to those of other G-7 and OECD firms.

- ^ "Territorial vs. Worldwide Corporate Taxation: Implications for Developing Countries" (PDF). IMF. 2013. p. 4.

- ^ "Tax Reform in the UK Reversed the Tide of Corporate Tax Inversions" (PDF). Tax Foundation. 14 October 2014.

- ^ "How Tax Reform solved UK inversions". Tax Foundation. 14 October 2014.

- ^ "The United Kingdom's Experience with Inversions". Tax Foundation. 5 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. p. 31.

Table 2: Shifted Profits: Country–by–Country Estimates (2015)

- ^ "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". The Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ^ "Half of U.S. foreign profits booked in tax havens, especially Ireland: NBER paper". The Japan Times Online. The Japan Times. 10 September 2018.

Ireland solidifies its position as the #1 tax haven," Zucman said on Twitter. "U.S. firms book more profits in Ireland than in China, Japan, Germany, France & Mexico combined. Irish tax rate: 5.7%.

- ^ Clemens Fuest; Christoph Spengel; Katharina Finke; Jost Heckemeyer; Hannah Nusser (15 October 2013). "Profit Shifting and "Aggressive" Tax Planning by Multinational Firms" (PDF). Centre for European Economic Research, (ZEW).

- ^ "Intellectual Property Tax Planning in the light of Base Erosion and Profit Shifting". University of Tilburg. June 2017.

- ^ Dhammika Dharmapala (December 2008). "What Problems and Opportunities are Created by Tax Havens?". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 24 (4): 3.

- ^ Philip Baker OBE QC (September 2013). "The Tax Treaty Network of the United Kingdom" (PDF). International Taxation. 9 (13).

The United Kingdom has 122 bilateral, comprehensive, double taxation conventions in force. It remains the largest number of tax treaties of any one country in the world. The United Kingdom may no longer be the world leader in manufacturing cars, or in playing football... however we are still the leading country in the world in negotiating double taxation conventions.

- ^ "UK tops global table of damaging tax deals with developing countries". The Guardian. 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Blacklisted by Brazil, Dublin funds find new ways to invest". Reuters. Reuters. 20 March 2017.

- ^ "Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America". Tax Justice Network. 6 April 2017.

- ^ "MOF rejects claim of Singapore as tax haven". The Straits Times. 14 December 2016.

- ^ "Singapore's government says it's not a tax haven, it's a value-adding IP hub". Sydney Morning Hearald. 30 April 2015. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Multinationals pay lower taxes than a decade ago". Financial Times. 11 March 2018.

- ^ "DE CORRESPONDENT REVEALS HOW THE NETHERLANDS BECAME TAX HAVEN". Oxfam/De Correspondant. May 2017.

- ^ George Turner (November 2017). "The Professionals: Dealing with the enablers of tax avoidance and financial crime" (PDF). Tax Justice Network.

- ^ "Explainer: what is a tax haven? The most important feature of a secrecy jurisdiction is that local politics is captured by financial services interests". The Guardian. 9 January 2011.

This political capture produces one of the great offshore paradoxes: these zones of ultra–freedom are often highly repressive places, wary of scrutiny and intolerant of criticism.

- ^ "Tax Justice Network: Captured State". Tax Justice Network. November 2015. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ "Revealed: Project Goldcrest, how Amazon worked with the Luxembourg Government to avoid huge sums in tax with IP". The Guardian. 18 February 2016.

- ^ Alex Cobham; Chris Jones; Yama Temouri (2017). "Tax haven networks and the role of the Big 4 accountancy firms" (PDF). Journal of World Business.

Our key findings demonstrate that there is a strong correlation and causal link between the size of an MNE's tax haven network and their use of the Big 4

- ^ Nicholas Shaxson (November 2015). "How Ireland became an offshore financial centre". Tax Justice Network.

- ^ "INTERNATIONAL TAXATION: Large U.S. Corporations and Federal Contractors with Subsidiaries in Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions" (PDF). U.S. GAO. 18 December 2008. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

Table 1: Jurisdictions Listed as Tax Havens or Financial Privacy Jurisdictions and the Sources of Those Jurisdictions

- ^ "Brussels in crackdown on 'double Irish' tax loophole". Financial Times. October 2014.

- ^ "Ireland's move to close the 'double Irish' tax loophole unlikely to bother Apple, Google". The Guardian. October 2014.

- ^ "Multinationals replacing 'Double Irish' with new tax avoidance scheme". RTÉ.ie. 14 November 2017.

- ^ "How often is the 'Single Malt' tax loophole used? The government is finding out". thejournal.ie. 15 November 2017.

- ^ Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Tørsløv; Ludvig Wier (November 2017). "€600 billion and counting: Why high-tax locations let tax havens flourish" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers.

- ^ Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Policy Failure of High-Tax Countries" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. pp. 44–49.

- ^ Ronen Palan; Richard Murphy (1 July 2011). "Tax havens: how globalization really works: Ronen Palan, Richard Murphy and Christian Chavagneux". Journal of Economic Geography. 11 (4): 753–756. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbr008.

- ^ "Gimme shelter - A survey of globalisation and tax". The Economist. 27 January 2000.

- ^ a b c James R. Hines Jr.; Eric M. Rice (February 1994). "FISCAL PARADISE: FOREIGN TAX HAVENS AND AMERICAN BUSINESS" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics (Harvard/MIT). 9 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

- ^ "Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting" (PDF). OECD. 2013.

- ^ "Base Erosion and Profit Shifting". oecd.org.

- ^ "TAX ANNEX TO THE SAINT PETERSBURG G20 LEADERS DECLARATION" (PDF). St Petersburg Tax Annex OECD. September 2013.

- ^ "What's Wrong With Intercompany Accounting? Plenty". BlackLine Magazine. 15 August 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "FEARGAL O'ROURKE: Man Making Ireland Tax Avoidance Hub Proves Local Hero". Bloomberg News. 28 October 2013.

- ^ "After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits". The New York Times. 6 November 2017.

A key architect [for Apple] was Baker McKenzie, a huge law firm based in Chicago. The firm has a reputation for devising creative offshore structures for multinationals and defending them to tax regulators. It has also fought international proposals for tax avoidance crackdowns.

- ^ Jack Power (10 November 2017). "Ireland resists closing corporation tax 'loophole'". The Irish Times.

- ^ "Scion of a prominent political dynasty who gave his vote to accountancy". The Irish Times. 8 May 2015.

Of the wider tax environment, O'Rourke thinks the OECD base-erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) process is "very good" for Ireland: "If BEPS sees itself to a conclusion, it will be good for Ireland."

- ^ Cobham, Alex (24 August 2016). "The US Treasury just declared tax war on Europe".

Second, it confirms (once again) that the OECD BEPS process has failed.

- ^ "OECD's BEPs measures seriously flawed". economia. 9 December 2016.

The major problem, it says, has been the decision by the Organisation in 2013 when it came up with its standard on country–by–country reporting (CBCR) to give into intense lobbying, largely from US multinationals, and place limits on access to the data.

- ^ "International Tax Advisory: Impact of the Multilateral Instrument on U.S. Taxpayers: Why Didn't the United States Choose to Sign the MLI?". Alston & Bird. 14 July 2014.

- ^ Mihir A. Desai (June 2018). "Tax Reform: Round One". Harvard Magazine.

- ^ "Google, Facebook and Salesforce.com dramatically expand their Dublin office hubs". Irish Independent. 26 July 2018.

- ^ "Irish Microsoft firm worth $100bn ahead of merger". Sunday Business Post. 24 June 2018.

- ^ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (18 July 2018). "When can we expect the next wave of IP onshoring?".

IP onshoring is something we should be expecting to see much more of as we move towards the end of the decade. Buckle up!

- ^ Ben Harris (25 May 2018). "6 ways to fix the tax system post TCJA". Brookings Institution.

- ^ "A Hybrid Approach: The Treatment of Foreign Profits under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act". Tax Foundation. 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Donald Trump seeks to slash US corporate tax rate". Financial Times. 27 September 2017.

Cutting the official corporate tax rate to 20 per cent from its present 35 per cent — a level that US companies say hurts them in global competition — would leave companies short of the 15 per cent Mr Trump promised as a candidate

- ^ a b Brad Setser, Council on Foreign Relations (6 February 2019). "The Global Con Hidden in Trump's Tax Reform Law, Revealed". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ Brad Setser (19 February 2019). "Why the U.S. Tax Reform's International Provisions Need to Be Reformed". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Why BEPS 2.0 makes tax heads nervous". International Tax Review. 4 February 2019. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Daniel Bunn (14 February 2019). "Ready to go on BEPS 2.0?". Tax Foundation. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b Cantillion (2 February 2019). "Ireland may soon run out of road on tax". Irish Times. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

In a policy note, the Washington-based think tank said US proposals to ensure companies pay taxes based on where they make their sales were gathering momentum and already had the backing of Brazil, China, India, and other emerging economies. Currently, the tax big companies such as Google and Facebook pay largely depends on where their assets, employees and head offices are located.

- ^ Dan O'Brien (3 February 2019). "Dan O'Brien: 'As Brexit gets all the attention, changes are afoot further afield'". Irish Independent. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Gavin McLoughlin (31 January 2019). "Irish corporation tax faces new squeeze as OECD kicks off digital reform probe". Irish Independent. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ "Base erosion and profit shifting - OECD BEPS". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "G20 Finance Communiqué, July 2021". www.g20.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "The Anti Tax Avoidance Directive". taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Tax Alert: Mandatory Disclosure Rules In Europe". vLex. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB)". taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 16 April 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Financing for Sustainable Development". www.un.org. Retrieved 16 April 2023.

- ^ "Standard for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information in Tax Matters, Second Edition | READ online". oecd-ilibrary.org. Retrieved 16 April 2023.