Avraham Stern

Avraham Stern | |

|---|---|

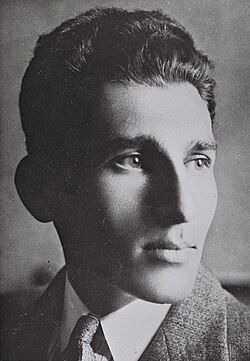

Stern in 1942 | |

| Native name | אברהם שטרן |

| Nickname(s) | Yair |

| Born | December 23, 1907 Suwałki, Russian Empire (present-day Poland) |

| Died | February 12, 1942 (aged 34) Tel Aviv, Mandatory Palestine |

| Cause of death | Execution by shooting |

| Buried | 32.072°N 34.804°E |

| Allegiance | |

Avraham Stern (Hebrew: אברהם שטרן, Avraham Shtern; December 23, 1907 – February 12, 1942), alias Yair (Hebrew: יאיר), was one of the leaders of the Jewish paramilitary organization Irgun. In September 1940, he founded a breakaway militant Zionist group named Lehi, called the "Stern Gang" by the British authorities and by the mainstream in the Yishuv Jewish establishment.[1] The group referred to its members as terrorists and admitted to having carried out terrorist attacks.[2][3][4]

Stern's legacy is controversial due to his organization unsuccessfully attempting to form an alliance with Nazi Germany against the British during World War II. He was captured and killed by British colonial police in 1942.[5]

Early life

Stern was born in Suwałki, present-day Poland (then the part of Poland that was under Russian Partition). During the First World War his mother fled the Germans with him and his brother David. They found refuge with her sister in Russia. When he was separated from his mother the 13-year-old Avraham earned his keep by carrying river water in Siberia. Eventually, he stayed with an uncle in St. Petersburg before walking home to Poland. At the age of 18, in 1925, Stern emigrated on his own to Mandatory Palestine.[6]

Stern studied at the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem. He specialized in Classical languages and literature (Greek and Latin). His first political involvement was to found a student organization called "Hulda", whose regulations stated it was dedicated "solely to the revival of the Hebrew nation in a new state."[7] During the 1929 riots in Palestine, Jewish communities came under attack by local Arabs, and Stern served with the Haganah, doing guard duty on a synagogue rooftop in Jerusalem's Old City.[8]

Stern's commander and friend Avraham Tehomi quit the Haganah because it was under the authority of the local labor movement and union. Hoping to create an independent army, and also to take a more active and less defensive military position, Tehomi founded the Irgun Zvai Leumi ("National Military Organization" known for short as the "Organization"). Stern joined the Irgun and completed an officer's course in 1932.

During his life, Stern wrote dozens of poems embodying a physical, almost sensual, love for the Jewish homeland and a similar attitude towards martyrdom on its behalf. One analyst referred to the poems as expressing the eroticism of death together with de-eroticism of women.[9] Stern's poetry was heavily influenced by Russian and Polish poetry, especially works by Vladimir Mayakovsky.[10] His song Unknown Soldiers was adopted first by the Irgun and later by the Lehi as an underground anthem. In it Stern sang of Jews who would not be drafted by other countries while they wandered in Exile from their own country, but rather who would enlist in a volunteer army of their own, go underground and die fighting in the streets, only to be buried secretly at night. One of the commanders of Lehi, Israel Eldad, claimed this song (along with two others, written by Uri Zvi Greenberg and Vladimir Jabotinsky) actually led to the creation of the underground.[11] In other poems from the same period, up to eight years before he founded the Lehi underground, Stern detailed the feelings of revolutionaries hiding in basements or sitting in prison and wrote of dying in a hail of bullets. One example of his poetry is: "You are betrothed to me, my homeland / According to all the laws of Moses and Israel… / And with my death I will bury my head in your lap / And you will live forever in my blood."[citation needed]

Stern became one of the university's foremost students. He was awarded a stipend to study for a doctorate in Florence, Italy. Avraham Tehomi made a special trip to Florence to recall him, in order to make him his deputy in the Irgun.[7]

Stern spent the rest of the 1930s traveling back and forth to Eastern Europe to organize revolutionary cells in Poland and promote immigration of Jews to Palestine in defiance of British restrictions (this was therefore known as "illegal immigration").

Stern developed a plan to train 40,000 young Jews to sail for Palestine and take over the country from the British colonial authorities. He succeeded in enlisting the Polish government in this effort. The Poles began training Irgun members and arms were set aside, but then Germany invaded Poland and began the Second World War. This ended the training, and immigration routes were cut off.[12] Stern was in Palestine at the time and was arrested the same night the war began. He was incarcerated together with the entire High Command of the Irgun in the Jerusalem Central Prison and Sarafand Detention Camp.

Lehi

While under arrest, Stern and the other members of the Irgun argued about what to do during the war. Following his release in August 1940, he founded Lehi in August 1940, initially under a different name, it adopted the name Lehi, a Hebrew acronym for Lohamei Herut Israel, meaning Fighters for the Freedom of Israel, in September 1940.[1] The movement was formed after Stern and others split from the Irgun when the latter adopted the Haganah's policy of supporting the British in their fight against the Nazis.

Stern rejected cooperation with the British and claimed that only a continuing struggle against them would eventually lead to an independent Jewish state and resolve the Jewish situation in the Diaspora. The British White Paper of 1939 allowed only 75,000 Jews to immigrate to Mandatory Palestine over five years, and no more after that unless local Arabs gave their permission.[13] But Stern's opposition to British colonial rule in Palestine was not based on a particular policy; Stern defined the British Mandate as "foreign rule" regardless of their policies and took a radical position against such imperialism even if it were to be benevolent.[14]

Stern was unpopular with the official Jewish establishment leaders of the Haganah and Jewish Agency and those of the Irgun. His movement drew an eclectic crew of individuals, from all ends of the political spectrum, including people who became prominent such as Yitzhak Shamir, later an Israeli prime minister, who supported Jewish settlement throughout the land, and who opposed ceding territory to Arabs in negotiations; Natan Yellin-Mor who later became a leader of the peace movement in Israel advocating negotiations and accommodation with the Palestinians, and Israel Eldad, who after the underground war ended spent nearly 15 years writing tracts and articles promoting an extreme right-wing, nationalist brand of Zionism.

Stern began organizing his new underground army by focusing on four fronts: 1) publishing a newspaper and making clandestine radio broadcasts offering theoretical justifications for urban guerrilla warfare; 2) obtaining funds for the underground, either by donations or by robbing British banks; 3) opening negotiations with foreign powers to save Europe's Jews and develop allies in the struggle against the British in Palestine; 4) actual military-style operations against the British.

None of these projects went well for the new underground. Without money or a printing press the stencilled newspapers were few and hard to read. The bank robberies and operations against British policemen resulted in street shootouts, and British and Jewish police were killed and injured. A British sting operation entrapped Stern into attempting to negotiate with the Italians, and this further tainted Lehi's reputation.[15]

In January 1941, Stern attempted to establish an agreement with the German Nazi authorities, offering to "actively take part in the war on Germany's side" in return for German support for Jewish immigration to Palestine and establishing a Jewish state. Another attempt to contact the Germans was made in late 1941, but no German response has been found.[16] These appeals to Germany were in direct opposition to the views of other Zionists, such as Ze'ev Jabotinsky, who wanted Britain to defeat the Nazis even as they wanted to expel the British from Palestine.[17]

According to Yaacov Shavit, professor at the Department of Jewish History of Tel Aviv University, articles in Lehi publications contained references to a Jewish "master race", contrasting the Jews with Arabs who were seen as a "nation of slaves".[18] Sasha Polakow-Suransky writes that "Lehi was also unabashedly racist towards Arabs. Their publications described Jews as a master race and Arabs as a slave race." Lehi advocated mass expulsion of all Arabs from Palestine and Transjordan,[19] or even their physical annihilation.[20]

Death

"Wanted" posters appeared all over the country with a price on Stern's head. Stern wandered from safe house to safe house in Tel Aviv, carrying a collapsible cot in a suitcase. When he ran out of hiding places, he slept in apartment house stairwells. Eventually, he moved into a Tel Aviv apartment rented by members of Lehi Moshe and Tova Svorai.

Moshe Svorai was caught by British detectives after they raided an apartment where two Lehi members were shot dead, and Svorai and one other man were wounded and hospitalized. Stern's Lehi contact, Hisia Shapiro, thought she might have been followed one morning and stopped bringing messages to Stern. On 12 February 1942, she came with one last message, from the Haganah, offering to house Stern for the duration of the war if he would give up his fight against the British. Stern gave Shapiro a letter in reply declining the offer for safe haven and suggesting cooperation between Lehi and the Haganah in fighting the British. A couple of hours later, British detectives arrived to search the apartment and discovered Stern hiding inside; the mother of one of the Lehi members had inadvertently led the police there.[21] Two neighbors were brought to attest to the propriety of the search. After they had left, Tova Svorai was also taken away so that Stern remained alone with three British armed policemen. Then, in circumstances that remain disputed today, Stern was shot dead.[22][23][24]

The report designated as "most secret" made by the police to the British mandatory government stated, "Stern was ... just finishing lacing his shoes when he suddenly leapt for the window opposite. He was halfway out of the window when he was shot by two of the three policemen in the room."[24] Assistant Superintendent Geoffrey J. Morton, the most senior policeman present, later wrote in his memoirs that he had feared Stern was about to set off an explosive device as he had previously threatened to do if captured.[24][25]

The police version was disputed by Stern's followers and others, who believed that Stern had been shot in cold blood.[24] Edward Hyams puts it laconically: "Stern was 'shot while trying to escape'."[26] Binyamin Gepner, a former Lehi member who in 1980 interviewed another policeman, Stewart, who had been present at Stern's death, said Stewart had effectively admitted Stern was murdered though, later, Stewart denied it.[24] The policeman whose gun was trained on Stern until Morton arrived, Bernard Stamp, said in a 1986 interview broadcast on Israel Radio, that Morton's account was "hogwash." According to Stamp, Morton pulled Stern from the couch on which he was sitting, "sort of pushed him, spun him around, and Morton shot him." Stamp has been cited saying Stern was killed while unarmed and with no chance of escape.[27]

Lehi attempted three times, unsuccessfully, to assassinate Geoffrey Morton. Morton eventually moved back to England, where he wrote his memoirs. He died in 1996, at the age of 89. He successfully sued four publishers of books which claimed he "murdered" Stern, including the English publisher of The Revolt. The publisher settled without consulting the author, Menachem Begin, who wanted to go to court.[24][28][29]

Descendants

Stern's son, Yair, born a few months after Stern's killing, is a broadcast journalist and TV news anchor who once headed Israel Television. His grandson Shay, is also a media personality and presenter in Israel.

Honours

An annual memorial ceremony is held at Stern's grave in the Nahalat Yitzhak Cemetery in Givatayim.[5] In 1978, a postage stamp was issued in his honor.[5]

In 1981, the town of Kochav Yair (Yair's Star) was founded and named after Stern's nickname.[5]

The place "where he was shot is a museum and place of pilgrimage for a growing number of hard-right youths".[30]

In January 2016, actor Steven Schub played the part of Avraham 'Yair' Stern in the world premiere of historian Zev Golan's play The Ghosts of Mizrachi Bet Street, based on the life of Avraham Stern directed by Leah Stoller and S. Kim Glassman at The Jerusalem Theatre in Israel.[31]

References

- ^ a b Nachman Ben-Yehuda. The Masada Myth: Collective Memory and Mythmaking in Israel. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: Wisconsin University Press, 1995. Pp. 322.

- ^ Calder Walton (2008). "British Intelligence and the Mandate of Palestine: Threats to British national security immediately after the Second World War". Intelligence and National Security. 23 (4): 435–462. doi:10.1080/02684520802293049. S2CID 154775965.

- ^ Arie Perliger, William L. Eubank, Middle Eastern Terrorism, 2006 p.37: "Lehi viewed acts of terrorism as legitimate tools in the realization of the vision of the Jewish nation and a necessary condition for national liberation."

- ^ Jean E. Rosenfeld, Terrorism, Identity, and Legitimacy: The Four Waves Theory and Political Violence, 2010 p.161 n.7:'Lehi ... was the last group to identify itself as a terrorist one'

- ^ a b c d Ginsburg, Mitch (20 February 2012). "The Rehabilitation of an Underground Revolutionary". Times of Israel. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem, p. 203

- ^ a b Nechemia Ben-Tor, The Lehi Lexicon, p. 320 (Hebrew)

- ^ Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem, p. 198

- ^ Moshe Hazani: Red carpet, white lilies: Love of death in the poetry of the Jewish underground leader Avraham Stern, Psychoanalytic Review, vol. 89, 2002, pp 1-48

- ^ Yaira Ginossar, Not for Us the Saxophone Sings, pp. 73-78, 85 (Hebrew)

- ^ Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem, p. 59

- ^ Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem, pp. 153, 168

- ^ J. Bowyer Bell, Terror Out of Zion, pp. 47-48

- ^ Israel Eldad, The First Tithe, p. 84

- ^ Nechemia Ben-Tor, The Lehi Lexicon, p. 87 (Hebrew)

- ^ Heller, J. (1995). The Stern Gang. Frank Cass.

- ^ "Terror Out of Zion", Elliot Jager, Jewish Ideas Daily.

- ^ Jabotinsky and the Revisionist Movement 1925–1948. Yaacov Shavit, Routledge; 1st ed., 1988) p. 231 "Articles in contemporary Lehi publications talked about the Jewish nation as a heroic people, even a 'master race' (in contrast to the Arabs, who were considered a nation of slaves)"

- ^ Sasha Polakow-Suransky, "The Unspoken Alliance: Israel's Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa", p. 107

- ^ "Religious Fundamentalism and Political Extremism", edited by Leonard Weinberg, Ami Pedahzur, p. 112, Routledge, 2008

- ^ James Barr (27 October 2011). A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Simon and Schuster. pp. 317–. ISBN 978-1-84983-903-7.

It was his mother who then inadvertently led the police...to Stern's hiding place in Tel Aviv, where ...Morton shot the...leader dead

- ^ Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem, pp. 231-234

- ^ Zev Golan, Stern: The Man and His Gang, pp. 41-45

- ^ a b c d e f I. Black, "The Stern Solution", The Guardian, Feb 15, 1992, page 4.

- ^ Geoffrey Morton, Just The Job, Some Experiences of a Colonial Policeman, pp. 144-145

- ^ Hyams

- ^ Zev Golan, Stern: The Man and His Gang, p. 45

- ^ Nachman Ben-Yehuda (1993). Political Assassination by Jews. State University of New York Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-7914-1166-4.

- ^ Max Seligman, attorney for M. Begin, letter to Oswald Hickson, Collier and Co., Solicitors, March 25, 1953, file no. 923, in Jabotinsky Institute Archives, file 49/3/13

- ^ Making of a martyr: How the killing of the head of the Stern gang echoes down the years, economist.com.

- ^ Orit Arfa (January 21, 2016). "Searching for Stern". The Jerusalem Post.

Sources

- J. Bowyer Bell, Terror Out of Zion: Irgun Zvai Leumi, Lehi, and the Palestine Underground, 1929-1949, (Avon, 1977), ISBN 0-380-39396-4

- Israel Eldad, The First Tithe (Tel Aviv: Jabotinsky Institute, 2008), ISBN 978-965-416-015-5

- Zev Golan, Stern: The Man and His Gang (Tel Aviv, 2011), ISBN 978-965-91724-0-5

- Zev Golan, Free Jerusalem: Heroes, Heroines and Rogues Who Created the State of Israel

- Avaraham Stern ("Yair") Archived 2007-06-07 at the Wayback Machine, by Hillel Kook at www.etzel.org.il - Profile at the Irgun website

- Patrick Bishop, The Reckoning: How the Killing of One Man Changed the Face of the Promised Land, (William Collins, 2014), ISBN 978-0007506170

- Hyams, Edward (1975) Terrorists and Terrorism ISBN 978-046-00786-3-4

External links

- Stern's poetry, essays, and letters (in Hebrew)

- The personal papers of Avraham Stern are kept at the Central Zionist Archives in Jerusalem. The notation of the record group is A549.

- 1907 births

- 1942 deaths

- People from Suwałki Governorate

- Polish emigrants to Mandatory Palestine

- Jews from Mandatory Palestine

- Haganah members

- Irgun members

- Lehi (militant group)

- Lehi members

- Executed revolutionaries

- People executed by Mandatory Palestine

- People killed in United Kingdom intelligence operations

- People shot dead by law enforcement officers in Mandatory Palestine

- Polish people executed abroad

- Polish revolutionaries

- Polish Zionists

- Yishuv during World War II

- Burials at Nahalat Yitzhak Cemetery

- Extrajudicial killings in Asia

- Extrajudicial killings in World War II

- Executed Jewish collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Executed Polish collaborators with Nazi Germany

- Prisoners and detainees of the British military

- Immigrants of the Fourth Aliyah

- People murdered by law enforcement officers