Auguste Henri Jacob

Auguste-Henri Jacob | |

|---|---|

Photo-card of Auguste-Henri Jacob in 1867. | |

| Born | March 6, 1828 |

| Died | October 23, 1913 (aged 85) |

| Resting place | Gentilly Cemetery |

| Occupation | Healer |

Auguste-Henri Jacob, better known as the Zouave Jacob, was born on March 6, 1828, in Saint-Martin-des-Champs, Saône-et-Loire, and died on October 23, 1913, in Paris. He was a renowned French healer during the Second Empire.

Jacob, the third trombone in the band of the Imperial Guard zouave regiment, first came to public attention in 1866 at the Châlons camp, where he performed some healings attributed to the supposed effects of his fluid. In the following year, his purported healings in greater numbers on rue de la Roquette in Paris made him famous, and he was notably caricatured by André Gill. However, this fame was short-lived, as two marshals soon debunked the press reports of an alleged healing.

Subsequently, the Zouave, who continued his healing activities until his death, garnered significantly less media attention, except for instances when he was prosecuted for the illicit practice of medicine, which established legal precedents. He died in 1913, leaving unresolved the questions of whether he was a charlatan or a miracle worker, and whether these healings were due to something beyond his powers of persuasion. According to several sources, his authoritarian healing methods foreshadowed those of evangelists. Several books appeared under his name, though it is uncertain if he was the author. After his death, his grave in the Gentilly cemetery became the site of persistent devotion.

Background

[edit]

Auguste-Henri Jacob was born in Saint-Martin-des-Champs, a locality that was subsequently incorporated into Saint-Jean-des-Vignes and subsumed by Chalon-sur-Saône.[2] His father was the proprietor of a chemical products factory in the area.[3] Following the demise of his mother, his father, who had remarried,[4] placed him in the care of his grandmother.[3] His education consisted of a single year at the village school of Saint-Martin-des-Champs, which he described as having focused exclusively on "basic reading and writing."[3] Subsequently, he pursued a career in the military, initially serving as a store clerk. He was subsequently enlisted in the army and served in the 7th Hussars and the 18th Infantry.[5] He was later transferred to the 1st Horse Chasseurs, where he learned to play the trombone in four months.[6] He concluded his military career with service in the 16th Artillery and 3rd Lancers.[7][5]

In 1858,[8] he terminated his employment and commenced work in a circus in Marseille. He performed trapeze under a free balloon floating 150 meters above the ground.[9][10] Following the accidental demise of his two acrobatic colleagues, he joined a Soullié circus in Nîmes, where he performed equestrian acrobatics with a monkey he had trained.[11][9][4][12] He also performed at provincial fairs in Oran and Marseille, handling weights of 25 kilos.[6]

He resumed his musical career with the Guard's zouaves, where he held the position of "third trombone."[7][5] His particular instrument was the baritone saxhorn, an instrument invented by Adolphe Sax.[13][14]

Châlons camp

[edit]The Châlons, a military camp established in 1857 in Mourmelon, attracted considerable public interest due to its maneuvers. The Zouaves of the Guard, whose camp was situated close to the imperial residence, consistently drew a substantial number of visitors, who were drawn to their tanned complexions, prominent beards, and distinctive attire.[15]

In 1866, while his Zouave regiment was stationed at the Châlons camp, Jacob commenced his career as the "most renowned healer of the nineteenth century."[16] The initial incidents are reported to have occurred during the summer months, although the details vary depending on the source. He is said to have healed either a young girl[N 1] or a cholera patient by placing his hand on their abdomen, which resulted in "violent reactions" and "convulsions in bed."[19] Alternatively, he is purported to have healed several of his ailing comrades in the infirmary, either through simple touch or merely by being present.[20]

When an officer at the camp inquired as to whether he truly believed he had cured genuine illnesses, Jacob responded, "It is not my responsibility to ascertain whether they were genuinely ill or if I genuinely healed them."[21]

In an article published on August 1, L'Écho de l'Aisne reported that numerous convoys of individuals with ailments were being transported to the Châlons camp. The article further noted that many of these individuals had returned to their homes with improved health.[22] On August 4, the same newspaper referred to "an actual army of the sick" arriving daily at the camp[18] and advised readers that only patients with "nervous system" issues should "visit and hope."[18] L'Éclaireur de Coulommiers estimated that approximately 20,000 individuals, many of whom were reportedly credulous, had visited the Châlons camp in the hope of being healed by the Zouave.[23] Military authorities intervened to prevent them from entering the camp without special permission, assigning a guard to Jacob[20][17] to "protect him from clients," according to Jacob.[24]

Subsequently, Jacob established a consulting office in a hotel in Mourmelon, where he could treat up to eighteen individuals per session. He later relocated to a larger hotel, where groups of twenty-five to thirty could attend.[18] Boivinet subsequently reported:

Some people want to speak: 'Silence!' he says; 'those who speak… I throw them out!' After ten to fifteen minutes of silence and general stillness, he addresses a few patients, rarely interrogates them, but tells them what they are feeling. Then, pacing around the large table where patients are seated, he speaks to everyone, without order; he touches them but without gestures resembling those of magnetizers.[18]

Boivinet estimated that the Zouave received 4,000 patients, which represented a reduction of approximately one-third compared to the estimates provided by Jacob. Of these patients, Boivinet noted that "one-quarter were healed and three-quarters were relieved."[18] However, he subsequently revised this estimate, stating that "of the 4,000 patients, one-quarter saw no results, and... of the remaining 3,000 patients, one-quarter were healed and three-quarters were relieved."[25]

Marshal Regnaud de Saint-Jean d'Angély, the camp commander, brought the sessions to a close on August 7, forbidding the public from approaching Jacob.[18][5] Boivinet stated that "the word 'Spiritism' was pronounced," although it is unclear by whom.[18] Jules Chancel (in 1897) attributed the intervention to the camp chaplain and doctors.[26]

-

Zouaves at the Châlons camp in 1866, photograph by Louis Joseph Gemmi Prévot.

-

Sick and ambulance at the Châlons camp in 1866.

-

In 1866, Mourmelon, the village next to the Châlons camp, was equipped with hotels to welcome visitors.

A controversial fluid

[edit]

The period of the Châlons events was characterized by a state of flux and instability, as evidenced by Honoré Daumier's series of caricatures, published in 1853,[27] which he titled "Fluid-Maniac". The contemporaries of the Zouave were willing to attribute his spectacular healings to "a law of unknown nature, exercised through an individual endowed with an intense magnetic power."[28] However, multiple paradigms competed to explain the situation. These included those of the mesmerists, who were divided into several schools, and the spiritualists, whose popularity continued to grow. As Le Magnétisseur noted, each group claimed Jacob as one of their own:

The spiritualists, not to be confused with the spiritists, recognize in him a seer […]; the spiritists see him as a sui generis medium; to the fluidists, he possesses the ultimate healing gift; his voice, his gaze, his will are all-powerful.[29]

Mesmerist explanations

[edit]

Jacob’s achievements are initially attributed to those of a magnetizer by the mesmerists.[31] Mesmer—whom Jacob characterizes as a "martyr"[32] who sought to "convince the world of scholars, especially doctors, his colleagues"[33]—held the conviction that humans were interconnected with the extraterrestrial realm through the currents and fluctuations of fluidic fields. He postulated that the harmonious distribution of these fluids was a prerequisite for optimal health and endeavored to rectify imbalances through magnetism.[34] As Mesmer perceived it, the objective of the magnetizer was to reinstate the equilibrium of these flows through the utilization of "passes" to "magnetize" the patient.[35] Amand Marie Jacques de Chastenet de Puységur, a disciple of Mesmer, employed a technique he termed "magnetic somnambulism" for therapeutic purposes. This concept, while foreshadowing the practice of hypnosis,[36][35] was not entirely identical to it.[37] Subsequently, magnetizers induced a hypnotic state in "somnambulists" to facilitate clairvoyance, description, explanation, and treatment of illnesses[38] such as rheumatism, stomach aches, insomnia, and amenorrhea.[39] These mesmerists, who retained their influence around the time of the events at Camp Châlons[40]—Louis Figuier even noting that magnetism was "the main exercise of military life"[41]—based their practices on the results of somnambulistic treatments, viewed themselves as scientists and were skeptical of the trend of table-turning and the theories developed by American spiritualists to explain phenomena associated with the Fox sisters or the clairvoyant Daniel Dunglas Home.[42]

By 1866, mesmerism had diverged into many distinct schools of thought:[42][35]

- Strict mesmerists, focused on a physicalist explanation, i.e., the fluid as a material vector of magnetism, and on the medical applications of electricity.

- Psychofluidists, considered the will as the agent of magnetic action but maintained the hypothesis of a fluid as a vector of this will.

- Spiritualists, some of whom explained the magnetizer's action not by a material fluid but by the effects of will and prayer, while others attributed it to the somnambulist's contact with angelic entities.

- Imaginationists, who believed neither the magnetizer's will nor any kind of fluid was involved. For them, magnetism merely released internal powers within the subject, the powers of the imagination.[43]

Kardecist explanation

[edit]

Although Jacob does not explicitly reject the concept of magnetism, he states that he is uncertain whether to attribute his "magnetic power" to spiritualism or magnetism.[44] He does, however, mention his "initiation into spirit science."[45][46] In 1897, he informed Jules Chancel, a journalist, that he had attended a spiritism session "by chance" and later recognized the existence of spirits and their potential for utilization in various capacities.[26] At that time, there were a considerable number of spiritist followers in France, estimated to be between 400,000 and two million.[47] However, it was challenging to differentiate between "conviction spiritism" and "recreational spiritism."[48][49] Some authors have even postulated the existence of a "latent spiritism" that pervaded society[50] in a context where the ties between the Church and the State were becoming increasingly tenuous.[51] The practice was particularly prevalent in the military, especially among the 3rd Lancers, where Jacob had previously served before becoming a Zouave.[52] The practice of healing mediumship experienced growth in France from 1865 onwards, with medical authorities demonstrating a relatively tolerant stance towards the illicit practice of medicine.[53] Kardec asserts that this practice is exempt from the aforementioned legislation, as it does not prescribe any specific treatment.[25] Additionally, as Guillaume Cuchet notes, while some medical professionals were initially skeptical of animal magnetism, they became more receptive to spiritism due to its lack of therapeutic claims, at least until 1866 and the success of the Zouave Jacob.[54] Following the successful demonstrations of healing at Camp Châlons, Kardec, who regarded spiritism as a scientific method based on observed facts,[55] asserted that "healing mediumship does not seek to supplant medicine and doctors; it merely seeks to prove to them that there are things they do not know and invites them to study them."[25][56]

In 1865, Maurice Lachâtre met a Zouave at the Paris Spiritist Society. Lachatre described the Zouave as a "fervent spiritist follower and writing medium" who received "mediumistic communications" of "remarkable superiority."[20] Additionally, he created intricate illustrations of unconventional flora and fauna, which he asserted originated from Venus.[57][58][59] In 1866, Allan Kardec asserted that he had been acquainted with Jacob for an extended period as a writing medium[N 2] and ardent proponent of Spiritism. Furthermore, he noted that Jacob had initiated preliminary efforts at healing mediumship before his tenure at Camp Châlons.[18]

In the view of Kardec, the healer was not merely a somnambulist but also a medium susceptible to the influence of spirits, which were identified with the souls of the departed[53] and "more or less endowed with the capacity to receive and transmit their communications."[62] He was an instrument of external intelligence, with therapeutic prescriptions by spiritist somnambulists being dictated by spirit doctors,[63] such as the "white-fluid spirits" frequently referenced by Jacob.[12][64][65] Kardec developed the concept of the perispirit (peri spiritus) as a "material fluidic envelope" surrounding the immaterial soul, which he believed enabled mediums to see and communicate with spirits.[63] Kardec distinguished between the magnetizer, who heals with his fluid, and the healing medium, who acts with the fluids of benevolent spirits. He asserted that the former is "always impregnated with the impurities of the incarnate."[66] Kardec's explanatory model integrated elements of magnetism into a larger system:

In the cases involving Mr. Jacob, Spiritism was scarcely mentioned, while all attention focused on magnetism [...]. It matters little whether the events are explained with or without the intervention of external spirits; magnetism and Spiritism go hand in hand; they are two parts of a single whole, two branches of science that complete and explain each other.[67]

As Guillaume Cuchet notes,[68] the Zouave Jacob’s "healing mediumship" was not unique: in 1867, in Bordeaux, a carpenter named Simonet, claiming to be a spiritist and nicknamed “the sorcerer of Caudéran,” performed hundreds of healings.[69][70]

Rue de la Roquette

[edit]

In October 1866, when his regiment was reassigned to the Versailles garrison,[20] Jacob continued his healing practice on a smaller scale, treating only a few individuals referred to him by friends or previous patients.[20] In the spring of 1867,[71] he accepted an offer from an industrialist named Dufayet to utilize a room in Faubourg Saint-Antoine to receive Parisian patients.[N 3] The location was 80 rue de la Roquette, situated at the end of a lengthy courtyard surrounded by industrial edifices.[20][74] His superior officer excused him from the majority of his obligations, enabling him to divide his consultations between Versailles and Paris. He treated patients from Versailles and its environs between noon and two o'clock in a café adjacent to the barracks, then proceeded by train to Paris, where he resumed sessions between three and six in Rue de la Roquette.[75]

The "miracles" of the Zouave

[edit]

In August 1867, reports of "miracles"[77][78] performed by the "Zouave of Rue de la Roquette" proliferated throughout Paris, disseminated by the press. It was rumored that he had healed the imperial prince,[79][N 4] and he was often presumed to be Jewish.[82][83][84][85][86][26] Jean-Jacques Lefrère and Patrick Berche posit that this supposition can be attributed to an "obvious parallel" with Christian thaumaturgy.[28][87] However, contemporaries more commonly linked these healings, sometimes ironically, to the Marian healings of La Salette and Lourdes, with which he "competed."[88][N 5] In his observations, journalist Eugène Woestyn noted that Jacob "wore the Crimean medal with the Sebastopol clasp," was "very intelligent," "had a lot of wit," "had read Gall and Lavater and possessed anthropology," but questioned whether people intended to make the Zouave "a new messiah" and whether they should "attribute the miracles that this soldier accomplishes so simply to the Virgin or any other saint."[90] In a letter to his readers, Anthony North Peat, a British press correspondent, wrote:

France is a Catholic nation and cannot do without miracles. Its faith might fade if there were not weeping virgins and healing Zouaves.[91]

The individuals who received healing varied according to the newspapers,[92] with estimates ranging from approximately one hundred to twelve to fifteen hundred.[77] Additionally, many of them were reportedly present in the courtyard, awaiting their turn.

The Paris correspondent for the Birmingham Journal provided an account of the sessions at Rue de la Roquette that was regarded as an eyewitness account, and which was widely reported in the British[94] and American press.[N 6] Before the commencement of the treatment, the Zouave would enter into a state of reverie, akin to a light trance, while the crutches were gathered in a corner of the room and the patients were seated in rows. Subsequently, he would traverse the room, diagnosing each patient and identifying the underlying cause of their ailment. The patients, gratified, departed without requiring their crutches. The description closely resembled Boivinet's account at Camp Châlons, including mention of Jacob's bluntness, with no "pretense to a prophet or inspired seer," stamping his foot and concluding the session with a "military" phrase: "clear out!"[97]

As North Peat notes, the medical community was unprepared to respond to the allegations, yet the veracity of the claims was not contested.[91] This observation is a point of emphasis for Allan Kardec.[98]

The initial reaction was one of astonishment [...] most of the articles were not written in a mocking tone; they conveyed doubt, uncertainty about the reality of such strange events yet tended more towards affirmation than denial.

Louis Veuillot offers a more nuanced perspective, noting that initially, those who "stubbornly denied" were "not listened to at all."[100] However, some commentaries diminish the significance of the "miracles" attributed to the Zouave, instead attributing them to psychological factors. In his work, Scientific journalist Wilfrid de Fonvielle — who refers to the Zouave as "Jacob-Davenport,"[101] a nod to the Davenport brothers, who were initially received at the Tuileries before being exposed as frauds in 1865[53][102] — expresses significant skepticism about the authenticity of Jacob's abilities[103] and underscores the pervasive superstitious atmosphere[103] surrounding the Zouave. He observes that thus far, no individual with the capacity to conduct a comprehensive examination of the phenomena associated with this "illuminated"[101] individual has been able to attend his sessions.[101] With irony, he states that he has "the regret of announcing" that he has observed "no miraculous occurrences."[101] Le Constitutionnel reports an example of a priest with an optical nerve paralysis who initially claimed to have been healed by Jacob, only to recant afterward, stating that he was "not at all better" and did not wish to appear "more foolish than others."[104] Alienist Prosper Despine employs an imagistic approach, emphasizing the role of patients in these treatments. "The Zouave Jacob appears to have produced notable outcomes among individuals who exhibited unwavering trust in his therapeutic abilities and whose conditions were attributed to dysfunctions within the nervous system, rather than organic damage."[105][106][107] A correspondent who claims to have attended the sessions at Rue de la Roquette expresses in The Lancet the opinion that Jacob "is unable to provide any benefit to paralytics whose limbs are already non-functional."[108] He asserts that the Zouave's treatment is confined to encouraging "patients in whom nervous influx is beginning to return to their limbs...who dare to stand and walk."[108] He posits that the purported "miracle of the Zouave" is constrained to "this insignificant progress, which, was already latent within the patient and made more visible by Jacob's strong will."[108]

In the context of persistent contention between official and empirical medical practitioners,[109][110] L'Union médicale, the publication of the Paris Hospitals Medical Society, articulates the disquiet of some doctors regarding the perceived charlatanism of the Zouave. They contend that despite Zve's strategic utilization of "some therapeutic methods which, by chance and on occasion, may yield favorable outcomes," he is nevertheless "practicing medicine illicitly, and the law can no longer be so flagrantly and repeatedly violated.[77]

Simultaneously, the Zouave's relationship with his superiors becomes increasingly tense. On August 4, Émile Massard reports that the Zouave Guard's music leader informed his colonel that Jacob "believes himself unassailable," asserts that "no one has the right to touch him," and claims that "if he were imprisoned, he would escape by supernatural means." Jacob's rationale for this assertion is that he has been "sent to earth to relieve suffering humanity."[76] In the view of the music leader, Jacob's actual objective is to be incarcerated so that "spiritualists and a few misguided individuals" will regard him as a "martyr of humanity."[76] He concludes:

I do not request harsh military punishment for the musician Jacob; but...I believe that musician Jacob is very dishonest and that all he has done so far is mere charlatanism![76][N 7]

The Zouave's healing abilities inspired a multitude of caricatures, the most renowned of which was created by André Gill. The caricature achieved considerable popularity[111] upon its publication,[112] with an estimated 200,000 copies sold.[113][114] Following the publication of an article by Francis Magnard in Le Figaro, which questioned the resemblance, Gill clarified that the caricature was based on a "highly accurate" photograph and claimed to have sold 75,000 copies within a week.[115] However, some have questioned the veracity of this claim.[116] Jacob appreciated the caricature and would later display it on the wall of his consultation room on Rue Lemercier.[117][118]

-

Paul Bernay (1867)

-

Bertall (1867)

-

Bertall (1867)

-

Bertall (1867)

-

Bertall (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1867)

-

Cham (1868)

-

Cham (1868)

-

Honoré Daumier (1867)

-

Fusino (1867)

-

Gédéon (1867)

-

André Gill (1867)

-

Carlo Gripp (1867)

-

Carlo Gripp (1867)[N 8]

-

Henri Meyer (1867)

The Marshals' sisavowal

[edit]In late August 1867, an incident occurred that called into question the credibility of the Zouave.[71] In an article published in La Petite Presse on August 24, Amédée Rolland reports that Marshal Forey, who is now suffering from hemiplegia, has requested the Zouave to provide him with treatment at his residence in Bourg-la-Reine.[121] In response to the marshal's aides-de-camp, Jacob asserts that it is not within his purview to provide medical services outside of his residence, citing legal constraints about the practice of medicine.[121] Upon learning of this refusal, Marshal Canrobert is said to have declared, "I shall bring him to you within two hours."[121] Jacob is then transported to Bourg-la-Reine, where Marshal Forey, transported on a stretcher and left alone in the garden with the Zouave,[121] is reportedly observed an hour later traversing the garden, leaning "with one hand on his companion's shoulder," then "suddenly stopping to embrace Jacob's head," and finally "throwing his cane in the air."[121]

On August 29, La Petite Presse published a clarification from an aide-de-camp of Marshal Forey, which dismissed the previous account as "a very amusing little story," wrongly presented as fact.[122] This retraction has a greater impact on the public than all the doctors' denials combined.[123] It specifies that the marshal has been able to walk for three months, supported on one side by a cane and on the other gently held by a servant.[122] The event is described as follows:

Without any preamble other than the customary military greeting, the Zouave first freed the marshal, despite his initial resistance, from his servant, whose role he assumed as support, then from his cane, and forced the patient to rely on his own limbs as much as his weakened muscles allowed.[122]

Adding to the controversy, a few days later, Le Figaro publishes a letter from an aide-de-camp of Marshal Canrobert stating that he "has never seen or heard of the Zouave Jacob and...has never had any involvement with this soldier, who is not under his command."[124]

The effect of these publications is instantaneous. Anthony North Peat states, "It is unclear whether Jacob still possesses self-belief, but Paris has ceased to believe in him."[91] At the beginning of September, consultations on Rue de la Roquette were suspended by order,[126] though the rationale behind this decision remains unclear. It is uncertain whether this was done to alleviate congestion on Rue de la Roquette,[5] implement an exercise ban,[108] address a request from local merchants, or due to complaints from the medical community.[127] In a letter to a British newspaper, Jacob explains the suspension, citing "difficulties from his superiors, who dislike the publicity given to a mere soldier" and "the police, who object to the congestion he causes on the street."[128] On September 10, Le Petit Journal reports that he "is serving a minor police penalty for missing an evening roll call," yet he maintains his intention to "return to Rue de la Roquette or elsewhere if unimpeded."[129]

The Zouave subsequently became the subject of plays in the vaudeville genre. The first performance of Le Trombone guérisseur by Marot and Buguet took place on September 15 at the Lafayette Theater; the premiere of Le Zouzou guérisseur by Savard and Aubert occurred on September 28 at the Folies-Saint-Antoine; and the premiere of Le Zouave guérisseur by Flor and Woestyn took place on the same day at the Saint-Pierre Theater. On the same day, Dechaume's Le Zouave de la rue de la Roquette was performed at the Saint-Pierre Theater. Additionally, on October 15, Flor and Woestyn's Le Zouave guérisseur was staged at the Déjazet Theater, achieving notable success.[119][120][130] Meanwhile, Jacob disseminates a document of sorts, which London's Illustrated Times reports he uses to clarify that he has not learned medicine from books, does not care for music, follows spiritualism, and is indifferent to the press's opinion.[131]

In July 1868, Jacob left the army and took up residence in a modest house at No. 10 Rue Decamps in Passy.[132] Accompanying him was his father, who assumed the roles of "doorman, assistant, and cashier,"[126] and a cousin who sold two photographs of Jacob, one in military uniform and the other in civilian attire, in the courtyard for one franc each.[132] The Zouave does not charge a consultation fee,[133][134] but prospective clients are required to purchase his photo before entering his office.[135] In addition to purported "miracles," he dispenses hygiene counsel to approximately sixty daily visitors.[136] This counsel, as described by the Belgian medical journal Le Scalpel, is "completely unscientific," including the prohibition of chocolate consumption, which he is said to view as "a mixture of dried meat and flour."[132] An English spiritualist who visited Jacob on Rue Decamps at the time offers a characterization of him as "the most intractable and unpleasant of individuals, with a vanity that hinders his work," and adds that he "often displays an unnecessary roughness and lack of courtesy that is greatly regrettable."[137] However, another reader of the same London spiritualist journal responds the following month, stating that he believes Jacob is "never rude" and is, on the contrary, "often gentle" with his clients. Furthermore, the reader notes that Jacob claims to be aided during sessions by "twenty to thirty spirits acting on the sick."[138] However, journalist Félix Fabart, who recalls his experiences from the time and whom René Guénon describes as "entirely favorable to spiritualism,"[139] suggests that the cures performed by the renowned Zouave were merely pseudo-healings. Fabart asserts that his clients consistently returned home with their original ailments and a new sense of discouragement.[140] He provides an illustration of a paralyzed individual, transported on another's back, who can walk unassisted for a brief period before returning to their original state:

The secret of his influence over the sick lay not in the assistance of spirits, as he claimed, but in the deplorable education he displayed. He terrified his clients with furious looks, occasionally adding salty epithets… Perhaps he was a tamer, but certainly not a miracle worker.[140]

In addition to the proceeds from the sale of photographs, Jacob's income also derived from the sale of his published works. In 1868, he published three works: Les Pensées du zouave, L'Hygiène naturelle par le zouave Jacob ou L'art de conserver sa santé et de se guérir soi-même, and Charlatanisme de la médecine, son ignorance et ses dangers, dévoilés par le zouave Jacob, appuyés par les assertions des célébrités medicales et scientifiques. The initial publication, Les Pensées du zouave, is, according to Allan Kardec, primarily composed of a series of 217 letters. These letters were "communications obtained by Mr. Jacob, as a writing medium, in various spiritualist groups or gatherings."[142] The work was published by Jean-Baptiste-Étienne Repos and became the subject of a dispute between Jacob and his publisher. Following the commercial failure of the publication, Jacob accused Repos of having made "untimely cuts" to the work.[141] Repos had modified the text (which, according to Le Tintamarre, remains "inept"[143]), having noted that in the manuscript, "spelling and syntax were barely respected, and in many places, the text was unintelligible or contained elements that were so extreme that it was impossible to publish."[144] The author asserts that the text had been altered, with Catholic professions of faith incorporated, along with a preface and an unflattering portrait, which elucidated the book's lack of commercial success, having sold fewer than 150 copies.[145][146] Despite the publisher presenting authorization from Jacob's father, he was ordered to pay the author 4,000 francs for breach of contract and damages.[N 10]

The Zouave in London

[edit]

In September 1870, Jacob fled the siege of Paris,[148] citing the "driv[en] out by war and revolution"[149][150] as the reason for his departure. Accompanied by a certain Robby, a spiritualist, he proceeded to London.[151] A welcoming assembly was convened on September 15 at the Progressive Library and Spiritual Institution,[152][153] a spiritualist gathering place.[154] His arrival was duly noted in several spiritualist periodicals.[152][153][155] During his investigation of religious phenomena in London,[156] Charles Maurice Davies, a clergyman and journalist at the Daily Star,[157] paid a visit to Jacob at 20 Sussex Place in Kensington.[149] It is noteworthy that Jacob exhibited a lack of proficiency in the English language, reflected in his limited patient intake, in stark contrast to the high volume of consultations he had received in Paris.[149][150] Davies noted a discrepancy between Jacob's assertion that he did not charge for his "sessions," relying solely on book sales, and an advertisement in The Medium and Daybreak that stated, "fees vary according to social status — the lowest rates apply to general sessions, and the highest to private sessions."[149][150] Jacob asserted that the "healing influence" or "fluid" did not emanate from him but from spirits surrounding the patient, whose ethereal assistance was guaranteed by his presence.[149] However, Davies remained unconvinced by his own experience:

He first told me that my left toe was cold, a statement I had to refute. Nor could I agree with Mr. Jacob that I was feeling tingling in my knees. I was then informed I had weakness in my back, to which I responded that I was unaware of any such issue.[149]

In a 1909 interview with Le Petit Parisien, Jacob gave a more flattering account of his stay in London. According to him, the press "made a colossal success" of him; he was introduced into "aristocratic English society" and invited to give concerts with "considerable success," after performing, as a sample of his talent, the Barber of Seville cavatina with "virtuosity" on a C trombone for the organizer of "musical soirées at court."[6]

The time of trials

[edit]

In 1871, Jacob was reported to have been "shot on November 28, 1870, as a traitor and spy."[159][160][161][26] It was subsequently determined that the individual in question was not the same person.[162] In 1873, following the report that the Zouave appeared "permanently lost,"[163] Le Figaro indicated that he had been located on Rue Ramponeau in the Belleville district. There, the Zouave had resumed his consultations[164] on a modest scale, combining "his profession of miracle worker with that of hat maker."[165][166] Subsequently, he relocated to Quai d'Auteuil,[167][168] subsequently to Rue Spontini, where he convened conferences on the detrimental effects of medicine before an audience of 150 to 200 individuals,[169] interspersed with performances of the trombone accompanied by a piano.[170][171] Additionally, Jacob possessed a singular assemblage of trombones, encompassing a vast array of varieties and dimensions.[4] His collection also included a piano and an organ-violiphone, a variant of the harmonium invented in 1879 by Jean-Louis-Napoléon Fourneaux.[172] In 1879, he extended the use of these instruments to the Scientific and Artistic Press Association.[173][174][158]

In 1880, the press recalled Jacob as the focal point of a legal dispute involving his wife, with whom he had allegedly conveyed a "cataleptic neurosis" and whom he was said to have regarded as his "savior, her God." She is reported to have prayed to him nightly, kneeling before his photograph. Additionally, Jacob's husband was described as having remained "resistant to his teachings" and "to supernatural matters."[175][176][177] Nevertheless, as several newspapers observed, the prominence of the Zouave had diminished, and a sense of quietude had descended around him.[144][178] In an article published in July 1883, Roger de Beauvoir, writing in the French newspaper Le Figaro, argued that Jacob was not absent from the public eye. While his star may have diminished somewhat, he continued to practice his gifts and treat approximately fifty patients daily on Avenue de Saint-Ouen. He relied solely on the sale of his photographic portrait, which "appeared to contain some of the model's magnetic power and was undoubtedly imbued with healing properties."[179] One month later, an article in La Presse indicated that the Zouave saw approximately two hundred patients daily.[180] Nevertheless, it was only during his trials for practicing medicine without a license that the press demonstrated a renewed interest in him.

A new paradigm

[edit]

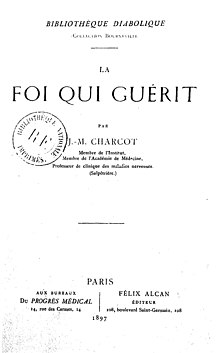

Following the death of Kardec in 1869, the rise of the moral order in 1873,[181] and the 1875 fraud trial of photographer Buguet, the "golden age" of spiritualism had effectively come to a close. In an 1882 work, Dr. Pauc observed the unexpected "total and voluntary abdication of reason" that had been represented fifteen years earlier by the "unprecedented vogue" of the Zouave among the so-called enlightened classes.[182] Concurrently, a novel explanatory model was emerging, one that was based on the scientific concept of hypnosis.[183] The medical field, under the direction of Professor Charcot at the Salpêtrière Hospital, concentrated its efforts on the study of hysteria.[184] These developments marked a clear break,[185] which Bertrand Méheust saw as a reclamation of the ideas of mesmerists,[186] supported by Braid's studies on hypnosis.[187] Replacing the mesmeric notion of somnambulism with hypnotism, Charcot reduced magnetism to a pathological phenomenon: the hypnotism of hysterical individuals. He therefore concluded that so-called magnetic somnambulists were hysterics,[188] and experimentally demonstrated their susceptibility to suggestion.[189]

In this new paradigm, Charcot concentrated his attention on cases such as the paralysis that Jacob successfully treated. In one lecture, he observed that he was only able to induce sleep in one of Jacob's patients following her fourth session with the Zouave, during which she experienced a significant nervous crisis marked by uncontrollable yawning, brief periods of convulsions, and loss of consciousness.[190] In his analysis of "paralyses by suggestion,"[191] which he also termed "hystero-traumatic,"[192] Charcot posited that they were predominantly susceptible to "psychic treatment."[191][N 11] However, he subsequently delineated the constraints of this approach to his audience at Salpêtrière:

In such cases of psychic paralysis, words alone are often enough to bring about the desired result suddenly. It may happen… that a miracle worker tells a patient: 'Stand up and walk!' and all of a sudden the patient, previously completely paralyzed in the lower limbs, indeed stands and walks. This is the well-known story of the successes of the famous Zouave Jacob… But be cautious in such matters… Do not forget that nothing can render one more ridiculous than proclaiming with some fanfare a result that may not occur.[192]

Hippolyte Bernheim, a neurologist who offered criticism of numerous aspects of Charcot's theories,[194] concurred with his assessment of Jacob's purported healings. Bernheim posited that Jacob was engaging in "suggestion without realizing it."[195][196] In 1913, journalist Émile Massard offered a humorous summary of the situation:

It is now clear that [Jacob] proceeded by suggestion [...]. Had he been better educated, he might have attained the reputation of Liébault and Liégois, the masters of the Nancy School.[76]

In the context of the anti-clerical climate that prevailed during the early years of the Third Republic, this explanatory model prompted a more generalised questioning of the phenomenon of miraculous healings. The credibility of healers was subjected to intense scrutiny, with many being exposed as charlatans. Additionally, the legitimacy of Marian apparitions[198] was challenged,[198] giving rise to a schism between the "School of Paris," comprising free-thinking doctors, and the "School of Lourdes," representing Catholic doctors.[199] The debate encompassed the question of whether Bernadette Soubirous was hysterical[200] and whether her purported healings were phenomena of hypnotism.[201] Nicole Edelman observes that Dr. Boissarie, the director of the Lourdes Medical Verification Office,[202] asserted that Charcot, while meticulously examining approximately thirty patients who were sent annually from Salpêtrière to Lourdes before and after their pilgrimage, had never shared his findings nor ever visited Lourdes. In this context, Charcot published an article in 1892[203] on the topic of faith healing. In this article, he argued that ulcers, edema, and tumors may be linked to nervous diseases and that these diseases may be cured by restoring brain motor impulses through the processes of self-suggestion and active imagination, which are stimulated by a pilgrimage.[204][199] Charcot specified that faith healing requires "specific individuals and specific ailments, those susceptible to the influence that the mind exerts on the body."[205]

In their 2011 study, Jean-Jacques Lefrère and Patrick Berche offered a nearly identical analysis to those previously discussed. They considered Jacob's "chamber miracles" to be a form of group psychotherapy[206] and referenced Leslie Shepard's 1991 view that the Zouave's authoritarian healing practices foreshadowed those later proposed by evangelical Christianity.[206][65]

Durvillard case

[edit]

In September 1883, Auguste Jacob was prosecuted for recklessness and the illicit practice of medicine.[207][208] As Nicole Edelman has observed, the offense in question was only punishable by a fine until 1892. During this period, the medical monopoly permitted a considerable degree of latitude for paramedical activities, including those of magnetizers and somnambulists.[209] Mrs. Durvillard, a peasant from Saint-Gervais-les-Bains, had sought the Zouave's counsel in May regarding arm pain. Jacob is said to have palpated her arm and twisted it with considerable force backward, resulting in a fracture of the humerus that was later diagnosed at Lariboisière Hospital.[210][211]

At the trial, Jacob presented his account of the events in question. He asserted that he had merely placed his hand on the woman's shoulder for approximately one minute, to allow the fluid to have a more pronounced effect.[212] Alternatively, according to another court account, he had pressed gently to facilitate the penetration of the fluid more rapidly.[213] Furthermore, he denied having exerted any force or violently twisted her arm before advising her to seek the attention of a bonesetter or a surgeon.[212] He further elucidated that his healing modality involves the application of a simple fluid to the eyes,[214] which he administers without any prior diagnosis of the underlying ailment.[215][216] Additionally, he expressed his opinion on the field of medicine, stating, "All doctors are charlatans."[212] This assertion was met with a response from the presiding judge, who noted that the Zouave advises in his brochures against seeking consultation from medical professionals.[217] In essence, Jacob's argument proposed that most illnesses are merely imaginary and that a kind word and a reassuring gaze are sufficient to facilitate a swift and complete recovery.[217] Several defense witnesses were called to the stand, and court reports highlighted the devotion of his clientele, which was described as "strange."[218][217] This clientele included "old women steeped in devotion, who lower their eyes as if at confession; completely illiterate peasants, domestics who can barely speak, and employees who believe in miracles."[218]

Notwithstanding the aforementioned supporters, Jacob was sentenced to six days of imprisonment and a fine of one hundred francs for negligence resulting in injury, five francs for the practice of medicine in contravention of the law, and five hundred francs in damages to Mme Duvillard.[219] According to Le Radical, upon exiting the courtroom, he was met by a throng of his devoted patients, and his conviction has generated considerable publicity.[220] He subsequently asserted that following his release, he undertook international travel, specifically to Germany, where he purportedly performed "miraculous healings for members of the court of Wilhelm I," and to England, "invited by ladies in the Queen's entourage,"[10] who, he claimed, presented him with a silver "honorary trombone,"[147][221][64] crafted by Besson and engraved with "offered by the ladies of the English court."[26][12] In 1884, the sentence was upheld on appeal[222] and again in cassation,[223][224] despite the submission of new testimonies.[225]

The Zouave's legal precedent

[edit]

In the wake of this conviction, Jacob proceeded to continue his practice on Avenue Mac-Mahon discreetly.[226] He continued to see approximately forty patients at a time, declining compensation and instead selling his photographs and brochures, which ranged in price from one to ten francs.[227] A banner in his consultation room read "Iesus Christna."[227][N 13] An 1890 article in Le Gaulois described the "strange" attire of the elderly charlatan, which Jules Bois later termed his "theurgic uniform:"[12][N 14]

He wears a sort of all-white smock, reaching down to his knees, with a hood like a monk’s robe. This outfit […] gives him a vague air of a dervish. He stands with his hands almost always clasped as if in prayer.[235]

In a subsequent interview conducted five years later by a journalist from Le XIXe Siècle, the subject was described in a manner that was strikingly similar to the previous account. This account pertained to an incident in which the individual in question was convicted for public indecency, specifically for urinating in his garden on Rue de Ménilmontant.[12] He is attired in a white beret, which is positioned with a certain degree of assurance on his head, a white smock, gray trousers, and patent leather shoes.[236] Jacob informed the journalist that he had "studied Allan Kardec" and subsequently "discovered by accident" that he possessed a healing fluid. He provided an additional explanation: "It is my belief that there are celestial bodies which, like the sun's emission of warmth to Earth, dispense a healing fluid that is received or stored by certain individuals."[236] The journalist then described the "curious spectacle" of a fluid dispensing session, which was attended by "five men and thirty-five women." These individuals were observed to be "heads bowed and eyes closed," adopting "beatific and church-devout postures." Some of the women were seen to be holding "shirts, flannel vests, stockings, handkerchiefs on their laps," which they "spread, turn, and twist" to facilitate the penetration of the healing fluid exhaled by the Zouave healer.[232] In addition to these group sessions, the Zouave held "theurgic gatherings," during which nearly three hundred participants joined Jacob in evoking "healing spirits" through songs accompanied by an organ and piano.[237]

Nevertheless, Jacob was rarely referenced in the press, and when he was, it was predominantly in the context of judicial developments, which invariably followed his legal difficulties, however minor. His fines in 1887 and 1891, resulting from his dog's bites to passersby, were consistently featured in headlines.[238][239] For example, in an 1891 recollection of an 1887 courtroom incident, the judge brought up Jacob's previous conviction for illegal medical practice. Jacob protested that he only used "the influence of a look in the eyes," which prompted the judge to quip, "In that case, you really should have looked your dog in the eyes to stop it from biting people."[240][241][242]

In 1891 and 1892, Jacob was charged with two additional instances of illicit medical practice.[243][244][245] In January 1893, he was tried for a fourth time on these same charges,[246] now classified as criminal offenses under the November 30, 1892 legislation.[247] To defend himself, Jacob asserted that his purported healings were the result of hypnotism, a practice explicitly excluded from the purview of the law in question.[248][249] This assertion prompted the prosecution to question the applicability of the law to Jacob's actions.[250] Ultimately, the judges ruled:

If the legislature did not reserve magnetic and hypnotic experiments exclusively to doctors, it is with the condition that laymen would remain within the realm of purely scientific experiments and would not enter into the domain of medicine proper, i.e., they would not use magnetism or hypnotism to practice healing as a profession.[251]

Thus, his exception was denied, and the Zouave was fined again.[252][253][254] Jacob appealed, arguing that the new law required a treatment, which he claimed he did not provide; however, the judgment was upheld because “the meaning of the word treatment is broad [and] cannot be arbitrarily restricted.”[255]

In 1909, he was once more prosecuted for the practice of medicine without a license.[256] In his defense, the defendant asserted that he did not engage in the practice of magnetism but rather served as a "healing medium, assisted by spirits."[257] His counsel advanced the argument that in 1867, Napoleon III had expressed a desire that Jacob never be prosecuted following a "decisive" intervention on behalf of the ailing imperial prince.[258][N 15] Among the Zouaves' defense witnesses was a local police commissioner, whose daughter Jacob had healed and who came to declare this formally.[259] The court concluded:

[The] action of Jacob, who does not question his clients, prescribe any remedy or medication, or provide any prescription, can only be seen as a mental invocation of spirits, whose intervention he boasts he can summon [and] it is impossible to confuse this act with medical treatment.[260][261]

While health professionals were taken aback by the leniency of the verdict,[264] Jean Lecoq penned an editorial in Le Petit Journal, entitled "Well Judged." In it, he argued that "we should leave these traditional, popular healers in peace, who, harming no one, do some good for a few."[265] However, the prosecution appealed, and the case was retried. On this occasion, the Zouave was sentenced to a one-hundred-franc fine and two hundred francs in damages to the Seine Physicians' Syndicate. The rationale behind this decision was as follows:

Illegal medical practice involves the fact that a person without a medical degree regularly or under ongoing guidance takes part in treating illnesses, except in cases of proven emergency; the meaning of the word treatment is broad and should include any act aimed at healing or alleviating a state of discomfort or illness; thus understood, any treatment does not necessarily imply the prescription of a regimen or remedy; nor does it require that the so-called healer know the illness being treated.[266][267]

Xavier Pelletier, writing in L'Intransigeant, awarded this ruling the “palms of martyrdom,”[268] while Jean Lecoq in Le Petit Journal expressed outrage: “In a sentence like the one just handed down, there is more than just odiousness; there is ridicule.”[269]

Jacob filed an appeal, with his lawyer arguing that the healing was carried out by an immaterial fluid communicated by spirits, which the Zouave merely transmitted.[270] The appeal was dismissed in April 1911 with a ruling stating that "any act or advice aimed at curing or improving a diseased state is considered treatment."[271][272]

The end of the Zouave

[edit]

In the final years of his life, the Zouave resided in the Batignolles district, where he was held in high regard.[273] In his account of the visit, René Schwaeblé described the subject as "robust and smiling, wise and mocking, fierce and subtle." He also noted that "his patients ... embraced him with tenderness."[118] Jacob led a reclusive existence, characterized by a lack of variety and a certain calm. He enjoyed robust health, which he attributed to the efficacy of his approach.[274] He was a staunch vegetarian, regarding meat as an "abominable scourge," and consumed solely vegetables, fruits, eggs, and Gruyère cheese, accompanied by red wine that he procured daily from a nearby bistro.[275]

He died in the autumn of 1913, at his home on rue Lemercier in Paris,[276][277] leaving unresolved questions regarding the relative merits of the miraculous cures attributed to Bernadette Soubirous and the Zouave, as well as the nature of his spiritual practices,[278] which have been variously described as a "kind of spiritist apostolate"[279] or a "naive charlatan."[280] Some have described him as "bizarre"[281] and "rather ridiculous," citing his belief in the "cooperation of spirits."[280] Others have questioned whether he possessed "the firm belief of truly possessing a supernatural power acting on the physiology and organism of his fellow humans."[126] Alternatively, he has been regarded as "a cunning one,"[26] a "charlatan exploiting and abusing public credulity."[126] Obituaries frequently highlighted his therapeutic use of the trombone, as evidenced by the following account from Paris médical: "He would fixate his gaze on the patient and play a tune on his trombone, prompting the patient to rise."[282]

He was initially interred in Saint Ouen Cemetery, but his remains were subsequently exhumed and relocated to Gentilly, where his sister had a private vault constructed for him.[283][N 16] This vault was inscribed with the words "Jesus Christna, Redeemer of the Hindus,"[N 17] and it was topped with a bronze bust of the Zouave, which was created by Athanase Fossé in 1892.[286][287]

Publications

[edit]

In his 1883 trial, Jacob was asked by the presiding judge about his profession. He replied that he was a "man of letters," and explained that his "fortune" was derived from selling his books to patients. His three principal publications, L'Hygiène naturelle par le zouave Jacob, Poisons et contre-poisons, dévoilés par le zouave Jacob et Charlatanisme de la médecine, son ignorance et ses dangers, dévoilés par le zouave Jacob, had reached their twelfth, eleventh, and eleventh editions, respectively.[288] Nevertheless, the veracity of his status as a writer was questioned by Pierre Larousse, who asserted that he had merely "authored a few books, or at least a few books appeared under his name."[2] Guillaume Cuchet also cast doubt on his literary abilities, claiming that he was "barely able to read or write."[46] Jean-Jacques Lefrère and Patrick Berche, for their part, advanced the view that he was "almost illiterate, but able to find devoted ghostwriters."[278]

Books

- Jacob (1868a). Les Pensées du zouave Jacob, précédées de sa prière et de la manière de guérir soi-même ceux qui souffrent [The thoughts of Zouave Jacob, preceded by his prayer and the way to heal those who suffer.] (in French). Paris: Repos. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.[2]

- L'Hygiène naturelle par le zouave Jacob ou L'art de conserver sa santé et de se guérir soi-même [Natural Hygiene by Zouave Jacob or The art of maintaining your health and healing yourself] (in French). Paris. 1868. Archived from the original on September 10, 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Poisons et contre-poisons, dévoilés par le zouave Jacob [Poisons and counter-poisons, revealed by the Zouave Jacob] (in French). Paris. 1871. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[N 19] - Jacob (1877). Charlatanisme de la médecine, son ignorance et ses dangers, dévoilés par le zouave Jacob, appuyés par les assertions des célébrités médicales et scientifiques [Charlatanism in medicine, its ignorance and dangers, revealed by the zouave Jacob, supported by the assertions of medical and scientific celebrities.] (in French). Paris.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Conférences sur les erreurs et les dangers des enseignements et pratiques des sectes sacerdotales, médicales, magnétiques et hypnotiques... d'après les témoignages écrits des plus grandes célébrités [Lectures on the errors and dangers of the teachings and practices of the priestly, medical, magnetic and hypnotic sects... based on the written testimonies of the greatest celebrities] (in French). Paris. 1887. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Théurgie et théurges [Theurgy and theurgists] (in French). Paris. 1887.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Procès du zouave Jacob : charlatanisme, ignorance, impuissance et agonie des corporations médicales : publiés par le zouave Jacob [Zouave Jacob's trial: charlatanism, ignorance, impotence and the agony of medical corporations: published by Zouave Jacob.] (in French). Paris: Bureau de la Revue théurgique. 1891.[N 20]

- Almanach théurgique du zouave Jacob, théurge guérisseur [Theurgic almanac of Zouave Jacob, healing theurgist] (in French). Paris. 1906.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[290]

Journals

- L'Anti-miracle, journal bimensuel [L'Anti-miracle, bi-monthly newspaper] (in French). Paris. 1884.

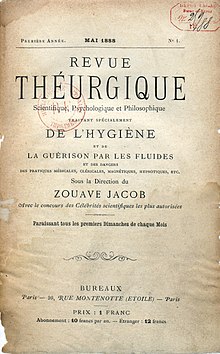

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Revue théurgique : scientifique, psychologique et philosophique : traitant spécialement de l'hygiène et de la guérison par les fluides et des dangers des pratiques médicales, cléricales, magnétiques, hypnotiques, etc. : sous la direction du Zouave Jacob, journal mensuel [Theurgical journal: scientific, psychological and philosophical: dealing especially with hygiene and healing by fluids and the dangers of medical, clerical, magnetic, hypnotic practices, etc. : under the direction of Zouave Jacob, monthly newspaper] (in French). 1888–1893. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.[N 21]

- Le Réformateur, journal bimensuel [Le Réformateur, bi-monthly newspaper] (in French). Asnières. 1892.

Legacy

[edit]Twenty-five years after the Zouave's demise, in 1938, Le Journal observed that his grave continued to be a site of pilgrimage for devoted admirers.[297] In a 2008 publication, Anne-Marie Minvielle observed that the Zouave's tomb in Gentilly continues to attract individuals seeking spiritual solace, as evidenced by recent plaques of gratitude. Many devotees, during their meditations, come to touch Jacob's bust, which is observed to have a polished appearance on the heart side.[298] In 1985, Vincent Delanglade posited that this devotion evidenced an "ongoing efficacy."[287] In 2011, Lefrère and Berche observed that Jacob "is the subject of a discreet cult," noting that his grave is The tomb is consistently adorned with floral offerings.[278] In 2012, Bertrand Beyern observed that the site is rarely devoid of candles.[299] Finally, in 2017, Michel Dansel concluded that the tomb is the most visited in the Gentilly cemetery.[300]

Some contemporary works make reference to him:

- The Zouave Jacob is a character in three novels by Feldrik Rivat: La 25e Heure (2015),[301] Le Chrysanthème noir (2016),[302] and Paris-Capitale (2017).[303][304][305]

- He also appears in La Canine impériale by Pierre Charmoz and Studio Lou Petitou.[306]

- Honoring the Zouave’s fondness for the trombone, jazz musicians Gianni Gebbia (alto saxophone), Mauro Gargano (double bass), and Dario De Filippo (percussions) named a CD after him, released in 2013.[307]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The case of the young girl itself has several versions: according to the account by Lefrère and Berche, she allegedly fell in front of the Zouave and hurt herself during a parade; he lifted her up, held her in his arms, told her she was healed, and she walked away smiling.[17] According to Boivinet, a spiritist and local informant for Kardec, she was in a small cart pulled by her parents, unable to walk for two years, her leg held in an orthopedic device. Jacob had the device removed, and the young girl walked.[18]

- ^ The "writer medium" produces a form of automatic writing under the dictation of spirits, and this practice, according to John Warne Monroe, implies a return to the mesmeric paradigm of the somnambulist.[60] In the 1860s, it was presented as an improvement over the rudimentary devices of the table-turning and the planchette.[61]

- ^ Sources vary on the details: Dufayet may have been a refiner,[72] a metallurgist,[71] or an iron merchant.[73] Jacob is said to have healed his daughter or his main employee in Châlons.[73] The room made available to him was either modest or spacious.[71]

- ^ Returning to the topic: Jules Troubat, the last secretary of Sainte-Beuve, recounts that the chief doctor of Val-de-Grâce reported to the latter that upon his return from the camp at Châlons, he had been extensively questioned by him, who sought his opinion on the Zouave Jacob.[80] The New York Times reported that the Zouave was received by the emperor at Saint-Cloud and that the imperial prince was "taken several times to the [Zouave’s] humble dwelling to be treated."[81]

- ^ Madame Blavatsky even added that the Zouave openly competed with the prophet Elijah by “bringing back to life people who seemed dead.”[89]

- ^ An American newspaper quoted this article verbatim and commented: "Needless to say, we do not ask our readers to believe a word of these extraordinary claims. We know nothing of the Paris correspondent of the Birmingham Journal, except that for a few years, he has been telling stories better than anyone in this paper; we do not know his name and are entirely unable to decide whether he saw all this, invented it, or—what is most likely—compiled it from reported stories while presenting himself as the hero of the tale."[95] The Medical and Surgical Reporter, on the other hand, "sees no reason to doubt such occurrences; far from being incredible, they are not even rare."[96]

- ^ Émile Massard claimed to have received this report from a "superior officer... who was Jacob's captain in the Zouaves of the guard."[76]

- ^ These caricatures illustrate some of the Zouave healer's lines in a one-act vaudeville play by Charles-Marie Flor and Eugène Woestyn, performed at the Déjazet theater in October 1867.[119][120]

- ^ Guillaume Walther, the author of the Zouave's song, had already published in Le Tintamarre the following verses: "What I appreciate most about him / Is that he operates under his own name. / To those who call him Messiah, / He gently replies: 'But no.'"[125]

- ^ In April 1883, the case returned to the courts. The principle of publisher liability was upheld on appeal, though the damages awarded to the Zouave were reduced.

- ^ Popularizer Charles Chincholle would even consider "the women who believed themselves healed" by the Zouave Jacob as "insane."[193]

- ^ The "Diabolical Library" was a collection created in 1890 by Bourneville, a disciple of Charcot, intended to publish anticlerical texts.[197]

- ^ The Zouave's relationship with faith is complex. Some authors believe he professed none,[228] while others think he healed in God's name those who had faith.[229] Jacob held a particular affection for Krishna, who he claimed was his "spirit guide,"[12] describing him as a wise figure over 8,000 years old from whom he had received teachings,[230] and to whom several articles in the Revue théurgique are dedicated.[231]

- ^ Returning again to the topic: René Guénon and Papus—who, while judging the Zouave's healings "indisputable,"[232] object to Pierre Mille describing the "master" Philippe as a "Zouave Jacob for crowned heads"[233][234]—agree in regarding the theurgy practiced by Jacob as a "vulgar mix of magnetism and spiritism," lacking the magical dimension that Neoplatonists associated with the term.[139][232]

- ^ Returning to the topic: Jules Troubat, the last secretary of Sainte-Beuve, recounts that the chief doctor of Val-de-Grâce reported to the latter that upon his return from the camp at Châlons, he had been extensively questioned by him, who sought his opinion on the Zouave Jacob.[80] The New York Times reported that the Zouave was received by the emperor at Saint-Cloud and that the imperial prince was "taken several times to the [Zouave’s] humble dwelling to be treated."[81]

- ^ The Zouave's sister also made it known through the press that she had "inherited her brother's fluid."[284] Ten years later, she would stand trial for attempting to get rid of her friend "by pouring petroleum on the room and bed where the man was sleeping and setting it on fire."[285]

- ^ This equates to INRI in abbreviation.[278]

- ^ Returning again to the topic: René Guénon and Papus—who, while judging the Zouave's healings "indisputable,"[232] object to Pierre Mille describing the "master" Philippe as a "Zouave Jacob for crowned heads"[233][234]—agree in regarding the theurgy practiced by Jacob as a "vulgar mix of magnetism and spiritism," lacking the magical dimension that Neoplatonists associated with the term.[139][232]

- ^ The Bibliothèque nationale de France also holds another edition with different pagination.[289]

- ^ The book bears the pre-title “Police correctionnelle” and would be issue no. 10 of the 3rd year of the Revue théurgique. The trial in question is from 1891.

- ^ Returning again to the topic: René Guénon and Papus—who, while judging the Zouave's healings "indisputable,"[232] object to Pierre Mille describing the "master" Philippe as a "Zouave Jacob for crowned heads"[233][234]—agree in regarding the theurgy practiced by Jacob as a "vulgar mix of magnetism and spiritism," lacking the magical dimension that Neoplatonists associated with the term.[139][232]

- ^ Several Rimbaldians have explored whether, in the poem "Paris" from L'Album zutique, the term "Jacob" refers to a pipe or—more likely—the Zouave.[293][294][295]

References

[edit]- ^ Journal militaire officiel [Official Military Gazette] (in French). 1854. p. 292. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Larousse, Pierre. "Jacob (Henri, dit le zouave)" [Jacob (Henri, known as the Zouave)]. Grand dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle [Great Universal Dictionary of the 19th Century] (in French). Vol. 17. Paris. p. 1450.

- ^ a b c Jacob 1868a

- ^ a b c de Pont-Jest, René (October 5, 1895). "Le zouave Jacob" [The Zouave Jacob]. Le Journal (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Trimm, Timothée (September 1, 1867). "La vérité sur le zouave Jacob" [The truth about Zouave Jacob]. Le Petit Journal (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Lagardère, Paul (May 19, 1909). "Un thaumaturge contemporain : une heure d'entretien avec le zouave Jacob" [A contemporary thaumaturge: an hour-long interview with Zouave Jacob]. Le Petit Journal (in French).

- ^ a b Claretie, Jules (November 9, 1867). "Courrier de Paris" [Paris Courier]. L'Illustration (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ "Le zouave Jacob". L'Intransigeant (in French). September 28, 1982. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Le zouave jacob". Le Radical (in French). September 27, 1892. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "Échos de Paris" [Echoes of Paris]. Le Gaulois (in French). July 20, 1890. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ "Le zouave Jacob". L'Industriel de Saint-Germain-en-Laye (in French). October 8, 1892. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Bois, Jules (1907). Le Miracle moderne [Modern Miracle] (in French). Paris: Paul Ollendorff. pp. 283–293.

- ^ "Hier - aujourd'hui - demain" [Yesterday - today - tomorrow]. Le Figaro (in French). September 12, 1867. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ "Le Zouave Jacob". Le Petit Journal (in French). September 13, 1867. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Bousquet, Charles (1858). La Garde impériale au Camp de Châlons [The Imperial Guard at Camp de Châlons] (in French). Paris: Blot. p. 206.

- ^ "Le guérisseur Philippe et ses confrères" [Healer Philippe and his colleagues]. Le Gaulois (in French). August 7, 1905. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Lefrère & Berche 2011, p. 571

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kardec 1866a

- ^ "Le zouave guérisseur en police correctionnelle" [The healing zouave in the criminal investigation department]. Mémorial de la Loire et de la Haute-Loire (in French). November 12, 1883. Archived from the original on September 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Lachâtre, Maurice (1867). "Médiums guérisseurs" [Psychic healers]. Le Monde invisible (in French) (1).

- ^ Hardy 1867, p. 5, quoted by de Cauzons, Thomas (1984). La Magie et la Sorcellerie en France [Magic and Witchcraft in France] (in French). Vol. 4. Geneva: Éditions Slatkine. p. 666. ISBN 978-2-05-100606-4. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ "Départements". La Presse illustrée (in French). August 6, 1866.

- ^ "Faits locaux et du département" [Local and departmental facts]. L'Éclaireur de Coulommiers (in French). September 9, 1866. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Frollo, Jean (November 13, 1883). "Le zouave Jacob". Le Petit Parisien (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kardec 1866b

- ^ a b c d e f "Les oubliés : le zouave Jacob" [The forgotten ones: Zouave Jacob]. L'Illustration (in French). May 8, 1897.

- ^ Pierssens, Michel (2007). "Fluidomanie" [Fluidomania]. Romantisme (in French). 138 (138): 75–88. doi:10.3917/rom.138.0075.

- ^ a b Lefrère & Berche 2011, p. 573

- ^ Chauba, E (1868). "Un homme s'il vous plaît" [A man please]. Le Magnétiseur : Journal du magnétisme animal (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Méheust, Bertrand (1993). "L'affaire Pigeaire : Moment décisif de la bataille du somnambulisme au XIXe siècle" [The Pigeaire affair: A decisive moment in the battle over sleepwalking in the 19th century]. Ethnologie française (in French). 23 (3). JSTOR 40989482.

- ^ Baron du Potet (1868). Manuel de l'étudiant magnétiseur [Magnetizer student manual] (in French). Paris: G. Ballière. p. 89.

- ^ Porter, Roy (2013). The Popularization of MedicineCouverture (in French). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-135-08699-2. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Jacob 1877, p. 8

- ^ Edelman 1995, p. 16

- ^ a b c Edelman 2008

- ^ Edelman 1995, p. 18

- ^ Peter, Jean-Pierre (2009). "De Mesmer à Puységur. Magnétisme animal et transe somnambulique, à l'origine des thérapies psychiques" [From Mesmer to Puységur. Animal magnetism and somnambulic trance, at the origin of psychic therapies]. Revue d'histoire du XIXe siècle (in French) (38): 19–40. doi:10.4000/rh19.3865.

- ^ Edelman 1995, p. 39

- ^ Edelman 1995, p. 45

- ^ Brower 2010, p. 8

- ^ Figuier, Louis (1860). Histoire du merveilleux dans les temps modernes [History of the marvelous in modern times] (in French). Vol. 3. Paris: Hachette. p. 241. quoted by Edelman 1995, p. 124

- ^ a b Monroe 2008, pp. 64–94

- ^ Méheust 2001

- ^ Hardy 1867, p. 5

- ^ Jacob 1868a, pp. 6–8

- ^ a b Cuchet 2012, p. 234

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 215

- ^ Chéroux & Fischer 2004, pp. 45–71

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 256

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 263

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 423

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 233

- ^ a b c Cuchet 2007

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 134

- ^ Edelman 2002, p. 95

- ^ Sharp, Lynn L (2005). "Popular Healing in a Rational Age: Spiritism as Folklore and Medicine" (PDF). Proceedings of the Western Society for French History (33). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 10, 2024.

- ^ Hardinge Britten, Emma (1899). Nineteenth century miracles, or, Spirits and their work in every country of the earth : a complete historical compendium of the great movement known as "modern spiritualism". New York: William Britten. p. 66.

- ^ "The Zouave Jacob" (PDF). The Spiritual Magazine. October 1, 1867. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 12, 2022.

- ^ Shepard, Leslie (1991). "Planetary Travels". Encyclopedia of Occultism & Parapsychology. Vol. 2. Detroit: Gale.

- ^ Monroe 2008, p. 95

- ^ Cuchet 2012, p. 111

- ^ Kardec, Allan (1861). Le Livre des médiums [The Book of Mediums] (in French). Paris: Revue spirite. p. 208.

- ^ a b Edelman 1995, p. 95

- ^ a b "Les guérisseurs" [The healers]. Le Soleil (in French). November 1, 1894. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b Shepard, Leslie (1991). "Jacob, Auguste-Henri ("Jacob the Zouave") (1828-1913)". Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. Vol. 1. Detroit: Gale. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024.

- ^ Revue spirite [Spiritualist magazine] (in French). Paris. 1874. p. 190. Archived from the original on November 12, 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kardec 1867b

- ^ Cuchet 2012, pp. 412–413

- ^ "Gazette des tribunaux" [Court Gazette]. Le Figaro (in French). July 7, 1867.

- ^ Kardec, Allan (1867). "Simonet. Médium guérisseur de Bordeaux" [Simonet. Psychic healer from Bordeaux] (PDF). Revue spirite (in French) (8). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Lefrère & Berche 2011, p. 572

- ^ Simond, Charles (1900). La Vie parisienne à travers le XIXe siècle : Paris de 1800 à 1900 d'après les estampes et les mémoires du temps [Parisian life through the 19th century: Paris from 1800 to 1900 according to prints and memoirs of the time] (in French). Paris: E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie. p. 662.

- ^ a b Hardy 1867, p. 3

- ^ Dangin, Édouard (August 31, 1867). "Le zouave de la rue de la Roquette" [The Zouave of rue de la Roquette]. La Rue (in French).

- ^ Hermant, A (August 27, 1867). "Le zouave aux miracles" [The Miracle Zouave]. La Petite Presse (in French).

- ^ a b c d e f Massard, Émile (October 28, 1913). "À travers l'histoire et le monde : le dernier thaumaturge" [Across history and around the world: the last thaumaturge]. La Patrie (in French).

- ^ a b c Simplice (August 24, 1867). "Causeries" [Talks]. L'Union médicale (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Hardy 1867, passim

- ^ de Fonvielle, Wilfrid (August 7, 1867). "Monde scientifique : le zouave de la rue de la Roquette" [Scientific world: the zouave of rue de la Roquette]. La Liberté (in French).

- ^ a b Troubat, Jules (1910). La Salle à manger de Sainte-Beuve [Sainte-Beuve's dining room] (in French). Paris: Mercure de France. p. 199.

- ^ a b "Zouave Jacob is dead: Famous as "Miracle Worker" Among Soldiers of Napoleon III". The New York Times. October 16, 1913.

- ^ Olivier, H (1867). "Chronique de la quinzaine" [Chronicle of the fortnight]. Journal des connaissances médico-chirurgicales (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ "The Zouave Jacob". The Albion, A Journal of News, Politics and Literature. September 21, 1867.

- ^ "The Zouave Jacob". Birmingham Daily Post. September 2, 1867.

- ^ The Spectator, quoted by The Living Age. New York: Littell, Son and Company. 1867. p. 45. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Shapiro, Arthur K; Shapiro, Elaine (2000). The Powerful Placebo : From Ancient Priest to Modern Physician. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 19.

- ^ Dementhe, Jules (1867). "Causerie parisienne" [Parisian chat]. Album de l'Exposition illustrée (in French).

- ^ Le Chrétien évangélique [The Evangelical Christian] (in French). Vol. 10. 1867. p. 631. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Blavatsky, Helena (1878). Theology. New York: J. W. Bouton. p. 22. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Woestyn, Eugène (August 19, 1867). "Le zouave guérisseur" [The healing zouave]. Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c North Peat, Anthony B (1903). Gossip from Paris During the Second Empire: Correspondence (1864-1869). New York: D. Appleton & Company. pp. 256–260.

- ^ M, V.-F (August 26, 1967). "Le zouave aux miracles" [The Miracle Zouave]. La Petite Presse (in French).

- ^ "Le Zouave aux miracles" [The Miracle Zouave]. Le Voleur (in French). September 6, 1867. Archived from the original on January 4, 2022.

- ^ Israel, Solomon (March 24, 1917). "Jacob, the Wonder-working French Zouave". Notes and Queries.

- ^ "The Zouave Jacob". Every Saturday: A Journal of Choice Reading. September 28, 1867.

- ^ "Modern Miracles". Medical and Surgical Reporter. October 5, 1867.

- ^ "Gossip from Paris". Birmingham Journal. August 24, 1867., reproduced in "The Zouave Miracle-worker". Harper's Weekly. August 25, 1867.

- ^ Kardec 1867a

- ^ Hermant, A (September 23, 1865). "M. Robin et les frères Davenport" [Mr. Robin and the Davenport brothers]. Le Monde illustré (in French).

- ^ Veuillot, Louis (1876). Mélanges religieux, historiques, politiques et littéraires [Religious, historical, political and literary mixtures] (in French). Vol. 4. Paris: L. Vivès. p. 83. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ a b c d de Fonvielle, Wilfrid (August 26, 1867). "Le Monde parisien" [The Parisian World]. La Liberté (in French).

- ^ Tabet, Frédéric; Taillefert, Pierre (2015). "Influence de l'occulte sur les formes magiques : l'anti-spiritisme spectaculaire, des Spectres d'Henri Robin au Spiritisme abracadabrant de Georges Méliès" [Influence of the occult on magical forms: spectacular anti-spiritism, from Henri Robin's Spectres to Georges Méliès's Spiritisme abracadabrant]. Mille Huit Cent Quatre-vingt-quinze (in French). 76 (76): 94–117. doi:10.4000/1895.5014.

- ^ a b de Fonvielle, Wilfrid (1872). La Physique des miracles [The physics of miracles] (in French). Paris: E. Dentu. pp. 8–10.

- ^ "Théâtres" [Theaters]. Le Constitutionnel (in French). September 2, 1867.

- ^ Despine, Prosper (1868). Étude sur les facultés intellectuelles et morales dans leur état normal et dans leurs manifestations anormales chez les aliénés et chez les criminels : psychologie naturelle [Study of the intellectual and moral faculties in their normal state and in their abnormal manifestations in the insane and in criminals: natural psychology] (in French). Paris: F. Savy. p. 593.

- ^ Despine, Prosper (1875). De la folie au point de vue philosophique ou plus spécialement psychologique, étudiée chez le malade et chez l'homme en santé [Madness from a philosophical or, more specifically, a psychological point of view, studied in patients and healthy people] (in French). Paris: F. Sav. p. 737. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.