Atoka County, Choctaw Nation

Atoka County was a political subdivision of the Choctaw Nation of Indian Territory, prior to Oklahoma being admitted as a state. The county formed part of the Nation's Pushmataha District, or Third District, one of three administrative and judicial provinces called districts.

History

[edit]The county was created in 1850 as Shappaway County, a name it held until 1854. Shappaway was a corruption of the Chickasaw or Choctaw words, shapah, or “flag,” and welih, “to hold up to view.” In late 1854 the General Council of the Choctaw Nation renamed it Atoka County in honor of Captain William Atoka. His surname, “Atoka,” is derived from the Choctaw word hitoka or hetoka, meaning “ball ground.”[1]

Captain Atoka was a noted athlete, distinguishing himself on the stickball playing field. Those who excelled in stickball were thought to be strong, brave, courageous, and intelligent. Atoka was a leader before the Choctaw removed to the west of the Mississippi River; he was a co-signer of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830.

Atoka lived in several locations in and around the present-day town of Atoka, dying at his home in October 1876. His grave was protected by a shed, which was maintained by friends and neighbors until Oklahoma's statehood. It remained in place through at least 1937.[2]

The county seat of Atoka County was the town of Atoka. This county was unusual among the Choctaw Nation's 19 counties for having a county seat that was also a population center. County seats were generally campgrounds used for tribal judicial or other proceedings. They had few if any permanent residents. Atoka, by contrast, was served by a railroad and developed as a trading center.

Atoka County's seat of government was located approximately one mile east of the present-day city of Atoka, Oklahoma. Although it leads in that general direction, modern-day Court Street does not reference the Atoka County Courthouse but, rather, a territorial-era United States Courthouse which was located on the street.[3]

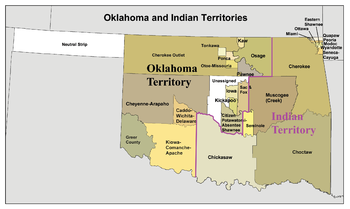

Atoka County's boundaries were established and designated according to easily recognizable natural landmarks, as were the boundaries of all Choctaw Nation counties. Its western boundary was the Choctaw Nation's western boundary with the Chickasaw Nation. Clear Boggy Creek formed most of its southern border, and Muddy Boggy Creek and North Boggy Creek formed its eastern borders. Its northern border skirted the Shawnee Hills to their south and connected with North Boggy Creek.

Atoka County served as an election district for members of the National Council; it was also a unit of local administration. Constitutional officers, all of whom served for two-year terms and were elected by the voters, included the county judge, sheriff, and a ranger. The judge's duties included oversight of overall county administration. The sheriff collected taxes, monitored unlawful intrusion by intruders (usually white Americans from the United States), and conducted the census. The county ranger advertised and sold strayed livestock.[4]

Statehood

[edit]As Oklahoma's statehood approached, its leading citizens, who were gathered for the Oklahoma Constitutional Convention, realized in laying out the future state's counties that, while logically designed, most of the Choctaw Nation's counties could not exist as economically viable political subdivisions. In most the county seat existed generally for holding county court and not as a population center. This was not true of the town of Atoka, nor was it true of Atoka County, which included large coal mines at Atoka, Coalgate and Lehigh within its territory. While Atoka County contained more sizable towns and industry than most, it would have to be dismantled in order to accommodate changes required by the region at large.

This conundrum was also recognized by the framers of the proposed State of Sequoyah, who met in 1905 to propose statehood for the Indian Territory. The Sequoyah Constitutional Convention also proposed a county structure that abolished the Choctaw counties. Atoka County was divided principally into the proposed Bixby, Blue, and Moseley counties. In so doing Sequoyah's framers first established the separation of Coalgate and Lehigh into their own county (Moseley County), separate from Atoka (in Bixby County), despite the short distance between the towns.[5]

Much of this proposition was borrowed by Oklahoma's framers two years later, who largely adopted the eastern boundary of the proposed Bixby County for the future Atoka County in Oklahoma and formalized the split-off of Coalgate and Lehigh into an adjacent county.

The territory comprising Atoka County, Choctaw Nation now falls within the present-day Atoka, Coal, Hughes, and Pittsburg counties. Atoka County ceased to exist upon Oklahoma's statehood on November 16, 1907.

References

[edit]- ^ "Organization of Counties in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations." Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 8, No. 3: 324, 330. September 1930.

- ^ “William Atoka Biography,” Indian-Pioneer Papers, Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries; “Organization of Counties in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations,” Chronicles of Oklahoma, Vol. 8, No. 3, September 1930, pp. 317–318, 324, 330.

- ^ A 1921 letter written by missionary Joseph S. Murrow, who ministered to the Choctaw Indians at Atoka and was a Confederate government official, noted the court grounds' location. See the reprint appearing in the interview with Mrs. Charles Maxwell, Indian-Pioneer Papers, Western History Collections of the University of Oklahoma Libraries. The location of the United States Courthouse is seen on Sanborn Fire Insurance Company maps held by the Library of Congress. Court Street was originally Hill Street, then 5th Street, and, after establishment of the United States Court, Court Street.

- ^ Constitution and Laws of the Choctaw Nation, 1890, p. 312; John W. Morris, Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, plates 38 & 56; and Angie Debo, The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Republic, p. 152.

- ^ Amos Maxwell, Sequoyah Constitutional Convention. Although the map carried in Wikipedia’s article on the State of Sequoyah speaks to the matter of borders, Maxwell’s book offers further insight.