Atlas des Géographes d'Orbæ

| Editor | Casterman-Gallimard |

|---|---|

| Author | François Place |

| Illustrator | François Place |

| Language | French |

| Genre | Illustrated album |

Publication date | 1996-2000 |

| Publication place | France |

| Awards | Amerigo Vespucci Award Bologna Children's Book Fair Sorcières Award |

| ISBN | 978-2-203-03004-6 |

| Followed by | Le Secret d'Orbæ |

The Atlas des Géographers d'Orbæ[note 1] (Atlas of the Geographers of Orbæ) is a series of illustrated books written and illustrated by François Place and published in three volumes between 1996 and 2000.

Presented as a geographic atlas written by the geographers of the lost island of Orbæ, the work comprises twenty-six chapters corresponding to the twenty-six letters of the Latin alphabet, each giving its shape and the first letter of its name to an imaginary country. The reader thus explores twenty-six territories, each introduced with a map, followed by a narrative accompanied by illustrations, and a final double-page spread of labeled sketches.

A true condensed universe that reinterprets the history and geography of the world as a coherent and intertwined whole, the Atlas combines a celebration of travel, discovery, and cultural exchange with an exaltation of the power of imagination and a reflection on its mechanisms, illuminated by numerous literary influences and abundant cartographic, geographic, historical, and cultural references.

Well-received by both French-speaking and international critics, the work helped establish Place as a talented writer and received numerous literary awards, including the Amerigo Vespucci Youth Prize in 1997, the Bologna Children's Book Fair Award in 1998, and a special Sorcières Award in 2001. It inspired several derivative works, including a sequel published in 2011, Le Secret d'Orbæ.

Presentation

[edit]General structure

[edit]The Atlas of the Geographers of Orbæ was originally published as three bound,[note 2] landscape-format volumes:[note 3] Du Pays des Amazones aux Îles Indigo (1996), Du Pays de Jade à l'Île Quinookta (1998), and De la Rivière Rouge au Pays des Zizotls (2000).[1] The work is presented as an atlas compiled by the geographers of the lost island of Orbæ:

The geographers of the great island of Orbæ claimed that the art of cartography alone could encompass all the natural sciences. They devoted themselves to describing phenomena both vast and minute. One spent his entire life creating the five hundred and eight maps of the underground world of ants in his garden, while another died before completing the grand atlas of clouds, which included not only their shapes and colors but also their various ways of appearing and traveling. Still others dedicated themselves to mapping tales and stories; they journeyed to the four corners of the world to gather them. Today, Orbæ has disappeared; all that remains of the work undertaken by its geographers is this Atlas.[2]

The work is divided into twenty-six sections, each dedicated to an imaginary country associated by its name and shape with a letter of the Latin alphabet: the first section is devoted to the "Land of the Amazons" (letter A), the next to the "Land of Bailabaïkal" (letter B), the third to the "Gulf of Candaâ" (letter C), and so on up to the "Land of the Zizotls" (letter Z).[3] Each section is structured similarly: a title page, featuring an illuminated map letter, the name of the country covered, and a brief introduction, which is followed by a story set in that country, accompanied by illustrations—including a large panoramic illustration at the incipit. At the end of each chapter, a double-page spread of labeled sketches complements the story and provides additional information about the territory and the people mentioned.[4][5] At the start of each volume, the general contents page displays the illuminated map letters of all the countries with their names and highlights the main narrative elements of their associated story[6] (notable aspects of the country visited, names of characters).[5]

Detailed summaries

[edit]

Volume 1

[edit]The first volume covers the letters A to I. In The Land of the Amazons, Euphonos, a highly talented but mute lutenist, stays in a town bordering the arid outskirts of the lush land of the Amazons—a fierce, all-female people whose singing has the power to rejuvenate nature and bring about spring. At the annual fair where they come to town to trade their furs, Euphonos plays his lute, and they join their voices with his music, healing the lutenist from the deep-seated sorrow caused by his muteness.[7]

In The Land of Bailabaïkal, structured around a clear water lake and a brackish lake, the old shaman Three-Hearts-of-Stone—destined for his role from birth due to his heterochromatic eyes—faces the arrival of a missionary seeking to convert his people. As the missionary also has heterochromatic eyes, Three-Hearts-of-Stone invites him, if he wishes to preach, to take over his role by wearing the shaman's cloak, which is inhabited by misaligned spirits that inflict terrible suffering on its wearer.[8]

In The Gulf of Candaâ, young Ziyara accompanies her father to the wealthy port city of Candaâ to deliver flour and honey for making the Elders' Bread, a massive gingerbread prepared from local produce and spices brought by the city's prestigious merchant fleet, distributed each year to the population. During the tasting, Ziyara finds a small ivory dolphin in her piece of bread, which comes to life upon contact with water. The City Elders explain that, according to an ancient scroll, the person who possesses this dolphin is destined to become the greatest admiral of the city of Candaâ.[9]

In The Desert of Drums, the nomadic khans ruling over this expanse of quicksand must, each year, journey to the mountains at the desert's center when drumrolls are heard, to sacrifice nine of their young warriors so that the gods may bring rain. To save his daughter, who was taken to be married to one of the young men before his sacrifice, the farmer and former soldier Tolkalk, visited in a dream by the gods, adds nine warriors sculpted from clay by his own hands to the vast terracotta army that lies dormant in a crypt under the mountains, thereby putting an end to the sacrificial tradition.[10]

In The Mountain of Esmeralda, the warrior Itilalmatulac of the Five Cities Empire—an Andean-inspired pre-Columbian state—leads an expedition to find the strange "red-bearded warriors" seen in a vision by the Sages of the Five Cities. Encountering them as exhausted conquistadors entrenched in a fortress atop Esmeralda Mountain, he consumes "travel herb" to enter their dreams and gain insight into their world of origin. He then lulls them to sleep with sacred chants and sends them downstream on a raft.[11]

In The Frosted Land, the Inuit Nangajiik recounts the story of his father, saved from death during a bear hunt by a dog that appeared out of nowhere. As the tribe prepares to endure the polar night in a cave within an iceberg, they welcome a young woman carrying a baby, who introduces herself as the wife of the dog. She brings an unfamiliar tenderness to her adopted community, before departing with her child and the dog at the sun's return; they leave behind the footprints of a young woman, a child, and a man.[12]

In The Island of Giants, young John Macselkirk, laird of a modest rural estate in Scotland since the death of his parents and recently the sole caretaker following his grandfather's passing, discovers an underground passage on his land that leads to a strange island inhabited by statues of giants. Each giant's chest contains a pebble of golden amber with captivating reflections. After several explorations of the island, he returns home and finds a similar stone near his grandfather's grave.[13]

In The Land of the Houngalïls, the territory of the bandit lords of the Houngür Mountains, the physician Albinius is tasked by one such lord, Sordoghaï, with winning the heart of the proud princess Tahuana of the land of the Troglodytes, whom Sordoghaï has kidnapped to marry. Over time, through discussions with both Sordoghaï and Tahuana, Albinius ultimately persuades Sordoghaï to release her. However, her experience changes her, and she returns years later to "abduct" Sordoghaï in turn and marry him.[14]

Finally, The Indigo Islands tells the story of Cornelius van Hoog, a "merchant from the lowlands," who has recently acquired a mysterious "cloud cloth." On a rainy evening, he stops at an inn run by Anatole Brazadîm, formerly a cosmographer on the great island of Orbæ. Brazadîm recounts his past expedition to the distant Indigo Islands, lost in a sea of grass in the heart of Orbæ, where he attempted to reach the "Sacred Island"—an extinct blue volcano believed to be unreachable—using a flying machine he invented. Fascinated by the story, Cornelius later returns to find Brazadîm gone, having left behind a memoir on the Indigo Islands that mentions the famous cloud cloth, inspiring Cornelius to set out on his journey in search of them.[15]

Volume 2

[edit]

The second volume covers the letters J to Q. In The Land of Jade, Han Tao, an apprentice astrologer, is tasked by the Emperor to discover why his two masters failed to predict the rains that disrupted the imperial stay in the Jade Mountains. Investigating the "sun-birds" that astrologers use to identify the sunniest valleys, he concludes, after a brief inquiry, that the problem lies in the declining quality of the honey used to make the cakes employed in training the birds,[note 4] causing them to wander and making them unfit for their task.[16]

In The Land of Korakâr, a Sahel-like territory where horses are of great cultural importance, the blind child Kadelik, who is passionate about horses and drums, travels with his grandmother to the grand festival of the Ten Thousand White Mares. His grandmother's fatigue makes their journey arduous and lengthy, even with the help of a mute lutenist they meet along the way, but Kadelik eventually reaches the festival and makes the horses dance to the sound of his drum.[17]

In The Land of Lotus, Zenon of Ambrosia, captain of a ship in the Candaâ fleet, is diverted by a storm and anchors at Lang Luane, the gateway to the vast Land of Lotus, governed by the King of Waters. Leaving his ship under the command of his first mate, a young woman named Ziyara, he sets out to explore the marvels of this land of lakes, marshes, and waterways, where he eventually decides to settle.[18]

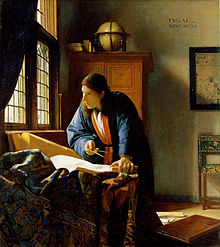

In The Mandragore Mountains, the cartographic engineer Nîrdan Pacha is tasked with leading a mapping expedition in this hostile, remote mountainous province at the edge of the "Empire," ruled by Sultan Khâdelim the Just. However, his encounter with a local sorcerer ultimately leads him to stay there permanently, becoming an apprentice to the sorcerer and eventually a sorcerer himself.[19]

The tale The Two Kingdoms of Nilandâr recounts the fratricidal war between Nalibar and Nadjan, the two sons of the king of this Indian-like land. Jealous of his brother's happiness, Nalibar wages war against him, ravages his territory and causes his death, only to face revenge years later from Nadjan's son, Nandjadîn, who defeats Nalibar and brings about his demise.[20]

The following story, The Island of Orbæ, tells of Ortélius, a renowned cosmographer who falls into disgrace after organizing an unauthorized expedition to the inner lands of this vast island, which only results in the discovery of barren, black lands and the capture of a misshapen, squawking bird. At his trial for "geographic heresy," he reveals that, before his expedition, he had personally spilled an ink blot on the Mother Map, a monumental map of the inner lands kept under special care, and had asked the Child-Palimpsest, a child with sharp vision who assists in map interpretation, to draw a bird near the ink stain... which allowed Ortélius, once in the field, to indeed discover the black lands and the bird as depicted on the map.[21]

In The Desert of Pierreux, Kosmas, the ambassador of the Empire, is sent among the Stoners, a strange people known for their slowness, who travel on the backs of giant tortoises across their vast rocky desert. At their request, the scholar Lithandre, who has shared their life for decades, has recorded their history in the form of thousands of scrolls that they want to deposit in the Great Library of the Empire. Kosmas agrees to accompany this long journey to the library, but the Stoners are met with suspicion in the villages of the Empire they pass through, and the scrolls are burned one night, leaving only the stone urns that contain them, vitrified by the fire. However, the Stoners seem to prefer this new form of their books and quietly return to their desert with Kosmas, who has decided to settle permanently among them.[22]

Finally, The Island Quinookta follows the struggles of the crew of the Albatross, a whaling ship commanded by the cruel Captain Bradbock, with the cannibals of a mysterious volcanic island. All are killed and eaten, except for the captain, who is recognized by the natives as the Quinookta, "The One-Who-Brings-Food," and kept for sacrifice in the mouth of the volcano.[23]

Volume 3

[edit]

In The Land of the Red River, the former slave trader Joao visits the sub-Saharan kingdom of the King of Kings, guided by his Minister of Speech, Abohey-Bâ. Though fascinated by this country, whose ruler possesses the secret of speech to animals and whose Minister of Speech keeps the Venerable, a monumental book from ancient times, he eventually wants to return home. This desire causes him to lose all memory of his stay, reducing him to a half-mad beggar muttering incoherent words.[24]

On Selva Island, entirely made up of a single vast "tree forest" on which a whole ecosystem thrives, a dozen young people undergo a rite of passage consisting of fighting a flying tiger of Selva (the feline equivalent of a flying squirrel), a trial they overcome at the cost of one of their lives.[25]

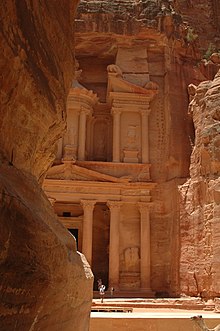

In The Land of the Troglodytes, the photographer Hippolyte de Fontaride is transported with his equipment by local porters to the rugged landscapes where once a wealthy civilization thrived, living in cities carved into the rock and worshipping the moon. Deciding to restore ancient wall frescoes depicting protective demons to immortalize them, he is disappointed by the result of his photographs, which only show a blurry fog. Only his porters, in the moonlight, can distinguish the silhouettes of their ancestors' ghosts.[26]

In The Desert of Ultima, a race of gigantic steam-powered vehicles is led by the powers of the Old Continent for the conquest of a vast, newly discovered territory: the first ship to reach the rock of Ultima, lost in the middle of a large central desert, will grant its nation dominion over the rest of these lands, which until now have only been inhabited by a few "primitive" peoples with aboriginal traits. These state-of-the-art machines, however, are destroyed one by one by a storm unleashed by an indigenous sorcerer.[27]

In The City of Vertigo, a massive pile of buildings stacked upon each other, the "flying mason" Izkadâr, who, along with his companions, helps maintain the city's buildings, is drawn into a sect led by the condemned Kholvino and the mage Buzodîn. Buzodîn claims that the comet that has appeared in the skies above the city for the past few nights is a sign of the city's impending destruction. He intends to hasten the event by descending into the city's underground, where he seeks the legendary Baliverne Stone, whose removal would cause the city to collapse. Despite Izkadâr and Kholvino's efforts to stop him, Buzodîn succeeds in carrying out his plan, but all he manages to do is cause a small localized landslide in which he perishes.[28]

The Wallawa River follows the evolution of a city built on this river, which flows in one direction during the day and in the other direction at night. The construction of a great clock by the talented master Jacob at the city's center gradually makes its inhabitants anxious and hurried, breaking the harmony they once shared with the river's natural cycles.[29]

In The Land of Xing-Li, renowned for its storytellers and tales, the old Huan never tires of hearing from an old woman the story of a Jade Emperor who fell madly in love with the portrait of an unknown young girl, to the point of abandoning his throne to spend his life searching for her. It turns out that Huan is none other than that Emperor, and the storyteller is the woman he once fell in love with.[30]

In The Land of the Yaléoutes, a peaceful tribe of hunters and gatherers is approached by the crew of a three-masted ship, which brings back Nohyk, the chief's son whom they had taken a year earlier to show him their land. At first seemingly benevolent, the sailors seek to take possession of the territory in the name of their king, which the natives see as nonsense, as they believe the land belongs to no one more than it belongs to the birds or the fish. While the commander retains the Old Man-with-Birds, the tribe's spiritual leader, aboard his ship to force him to sign an annexation treaty, the cannon fire he orders against the group coming to the old man's aid causes a huge section of the neighboring glacier to collapse, generating powerful waves that sink the ship.[31]

Finally, The Land of Zizotls, the last story of the triptych, follows the secret return to Orbæ of the cosmographer Ortélius, who was exiled over twenty years ago for geographical heresy. His journey intersects with that of an old retired traveler whose only regret is never having reached the mysterious Indigo Islands, described in a manuscript that the innkeeper Anatole Brazadîm had left him half a century earlier. Intrigued, Ortélius resumes this quest: using a flying machine inspired by Brazadîm's plans, he soars over the vast landscapes of Orbæ until he reaches an island in the middle of an ocean of grass. However, these are not the Indigo Islands, which the natives — the Zizotls — do not seem to know. Nevertheless, they lead him to a promontory, from the top of which he glimpses the distant blue cone of the Sacred Island, "like a full stop at the end of a strange alphabet."[32]

Genesis of the piece

[edit]

In 1985, the young François Place was tasked by Gallimard Jeunesse to illustrate a collection of five documentary works: La Découverte du monde (The Discovery of the World) (1987), Le Livre des conquérants (The Book of Conquerors) (1987), Le Livre des navigateurs (The Book of Navigators) (1988), Le Livre des explorateurs (The Book of Explorers) (1989), and Le Livre des marchands (The Book of Merchants) (1990).[33][34] While the text of the first two was written by Bernard Planche,[33] Place worked alone on the following three, which are the first works to bear his name.[35] To enrich their glossary, Place came up with the idea of drawing twenty-six small initial letters representing the twenty-six letters of the Latin alphabet in the form of maps, which would become the primary inspiration for the Atlas project.[33] At the same time, the bibliographic research he conducted for his documentaries led him to gather abundant documentation on geographical atlases and travel stories, which in turn sparked his interest in the evolution of mentalities and the way different peoples meet, perceive, and understand each other.[36]

In 1992, Place published Les Derniers Géants (The Last Giants), his first illustrated album. The success of the work enabled the author to propose a new illustrated album project to his editor, Brigitte Ventrillon of Casterman Publishing House: an atlas of twenty-six maps corresponding to the twenty-six letters of the alphabet to describe a world in its entirety, accompanied by documentary plates depicting the peoples, fauna, and flora of the mentioned territories. However, the editor judged the idea too simplistic after the success of Les Derniers Géants: she suggested that Place keep the idea of an alphabetical atlas covering twenty-six countries through maps and illustrations, but enrich each country's presentation with a narrative. This is how the project for L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ was born:[33] originally planned for two years, it ultimately occupied the author for six years.[37] The amount of information to process was such that several volumes were quickly deemed necessary, and the album initially conceived became a triptych.[38]

Place writes the stories one by one, not necessarily in the final alphabetical order.[39] His writing process first consists of letting the shape of the letter inspire him to define the general characteristics of the territory being treated;[37] then, he makes numerous sketches representing the inhabitants of the area and the main elements that constitute the country before finding an approach angle to begin his narrative,[40] which he then develops by drawing from a wide range of sources and influences,[41] which he records in the form of numerous cards and notes.[39] The writing proceeds with a constant back-and-forth between the text and the map, the map being rethought based on the text and vice versa.[42] The relationship between the text and the illustrations is also the subject of specific reflection: Place works on the images alongside the narrative to make them as harmonious as possible.[39] This relationship also governs the choice of format — which will be a landscape format that emphasizes the landscapes, even though this requires the text to be arranged in two columns[38] — and the layout, designed to allow a dialogue between the narrative and the illustrations. Special attention is given to the chapter openings: the author initially plans for a large introductory image across two pages but ultimately chooses to pair it with a column of text to start the narrative right away while immersing the reader in the place he describes through the illustration.[39]

Another important task is to link the narratives together: since the goal is not to deliver a structured and homogeneous world but rather "fragments of travel," Place quickly discards the idea of a general map encompassing the twenty-six countries visited.[38] However, he must ensure connections between the stories and incorporate elements that he had not always planned. For example, when he mentions the "giraffes of Nilandâr" housed in the gardens of Candaâ, he must later find a way to include these giraffes in The Two Kingdoms of Nilandâr.[39] In the end, to give structure to the triptych, he chooses three stories placed at strategic points in the work: The Indigo Islands, at the end of the first volume; The Island of Orbæ, in the middle of the second; and The Land of the Zizotls, at the end of the third,[38] which allows a return to the first two and makes the Atlas a coherent whole.[39]

Reception

[edit]

L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ received critical acclaim upon its release. Initially known primarily as an illustrator, François Place gained recognition for his writing talents as well.[43] The first volume, released in 1996, was described as a "magnificent album" by Olivier Barrot, who praised the rich imagination that the author built.[44] For writer François Bon, Place achieved the masterstroke of bringing the reader back to their childhood experiences and dreams of discovery, placing him in the same lineage as Pierre Loti and Jules Verne.[45]

The recognition was so great that the work was included in the curriculum for French middle school students (fifth and fourth grades) in 2000.[1] Outside of France, the English translation of the first volume, titled A Voyage of Discovery,[note 5] received admiration from Philip Pullman, who regarded Place as an "extraordinary artist," describing the work as "prodigiously inventive" and a "triumph of imagination and mastery." He considered it "one of the most astonishing works [he had] ever seen."[46]

The German translation, Phantastische Reisen (meaning Fantastic Journeys),[note 6] was praised in an article in the Tagesspiegel for its evocative power, suitable for both children and adults.[47] Additionally, the Chinese traditional version earned Place an invitation to the 2008 Taipei International Book Fair, where he was in high demand by both the media and the public.[48] The Atlas was also translated into Japanese and Korean.[49]

This critical success also translated into numerous awards: Place notably received the "Non-fiction for Young Adults" award at the Bologna Children's Book Fair in 1998 (for the first volume) and a special Sorcières award in 2001 (for the entire Atlas). The full list of accolades for the triptych also includes the Gold Circle of Youth Literature from Livres Hebdo magazine in 1996, the France Télévision Award in 1997, the Amerigo-Vespucci Youth Prize from Saint-Dié-des-Vosges in 1997, the "L" Prize from the Fête du Livre de Limoges in 1997 for the 10-14 years category, the "À vos livres" Prize from Issoudun in 1999, and the Chronos Prize in 1999 for the CM1-CM2[50] category; the work was also nominated for the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis in 1998 in the "Non-fiction" category, though it did not win the prize.[51] The Atlas also led to numerous exhibitions,[52] including at the Étonnants Voyageurs Festival in Saint-Malo in 1999[53] and the Taipei International Book Fair in 2008.[48]

Analysis

[edit]The composition of a world

[edit]

The passage describes the Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ as an attempt to portray a complete universe through a compilation of short stories.[54] These stories create a condensed world, almost like an encyclopedia,[55] immersing the reader in various periods and locations.[56] The temporal scope spans from the Age of Discovery to the colonial conquests of the 19th century.[57] As the work progresses, the stories move from medieval and ancient Greek settings to more modern references, like cities (La Cité du Vertige), mechanical advances (Le Désert d'Ultima), and photography (Le Pays des Troglodytes).[38]

This temporal mosaic is mirrored by a geographical mosaic: the stories unfold across all continents (the city on the Wallawa River seems European, The Land of Jade Asian, Selva Island South American...)[58] and in extremely varied landscapes, ranging from empires and kingdoms (Land of the Red River, Nilandâr...) to vast islands (Orbæ, representing the Terra Australis of ancient world maps)[59] or smaller ones (Selva), to cities (the city of Vertigo, the city on the Wallawa), deserts (the Drum Desert, Ultima), and wide territories with blurred boundaries (lands of the Amazons, Frissons, Korakar...).[60] Throughout the work, parallels are drawn to our world: the style of the maps resembles real historical maps or works, such as the map of Esmeralda, which resembles Mesoamerican codices,[61] the map of Nilandâr with its appearance of 17th-century Persian miniatures, or that of Ultima evoking 19th-century military maps.[62] The illustrations also suggest analogies with real locations, such as the winter landscape of the Wallawa River, strongly reminiscent of the Brabant landscapes painted by Pieter Brueghel the Elder in the 16th century.[63]

The names of territories are crafted in various ways: scientific pseudo-Latin (Orbæ, Ultima), evocative toponyms (Baïlabaïkal, Nilandâr), descriptive designations (Land of the Red River), connoted references (Land of Jade, Mandragore Mountains), and characters drawn from a shared cultural heritage (land of the Amazons, Island of Giants).[64] This blend of historical, geographical, and cultural elements helps to create a rich, immersive world in the Atlas.

The coherence of the world created in L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ is maintained by the interconnectedness of the places visited in the Atlas, which are woven into a common geographical and historical framework. The author establishes connections between different stories through the reuse of characters (like Ortélius from The Island of Orbæ, who reappears in The Land of Zizotls)[62] and by creating bridges between territories.[65] For instance, in The Gardens of Candaâ, wonders from other countries in the Atlas are displayed, such as the "laughing toads of Baïlabaïkal" or the "woolly giraffes of Nilandâr and Orbæ." Tolkalk, the hero of The Desert of Drums, has had adventures in The Land of Korakar, The Kingdoms of Nilandâr, and The Land of Xing-Li.[66] The Land of the Houngalïls is explicitly located between The Land of Jade and The Mandragore Mountains.

All of these elements create an ordered system structured around three main poles: the port city of Candaâ, which serves as the economic heart; The Land of Jade, a political and colonizing power; and the ideal Island of Orbæ, a cultural and spiritual center.[note 7][62] On the other hand, some territories appear more marginal, like The Desert of Pierreux, located on the edges of a vast unnamed Empire, or The Island of Giants, whose shifting position makes it difficult to locate.[60] This structure mirrors the contrast between the center and periphery that characterizes the relationships between real-world territories.[67]

The depth of the world sketched by Place is enhanced through a nesting effect. Several universes appear to be embedded within each other: for instance, The Island of Giants is accessible via a Scottish underground passage, The Mandragore Mountains[60] form a remote and mysterious territory on the borders of a vast unnamed Empire, and The Indigo Islands are lost at the heart of the Inner Lands, beyond the Mist Rivers of The Island of Orbæ, possibly in one of the areas marked on the Mother Map as Terra incognita ("unknown land") or Terra nondum cognita ("land not yet known").[69]

This nesting effect is also reflected in the narration, where sometimes treaties, such as Zénon d'Ambroisie's in The Land of Lotus,[70] and stories (legends, tales) are inserted within the main narrative.[71] Other ways to deepen the work include the illustrations: about the accompanying text, which creates a back-and-forth effect, they often depict vast landscapes with distant horizons, using perspective to give the illusion of extending to the dimensions of the world,[72] creating a sense of relief.[73] This is further emphasized by the inclusion of maps within the illustrations, creating an "image within the image" (such as the map of The Island of Giants drawn by the Candaâ Admiralty or the Mother Map of Orbæ depicted in the large room of Cartography, with many other maps hanging in the room).[74] Additionally, the appendices, encyclopedic double-pages, allow the author to extend beyond the scope of the previous adventure, bringing to life a whole microcosm through several sketches.[75]

Through these techniques, Place gives his work depth and coherence, making it a true universe—an idea reinforced by the very name of Orbæ, derived from the Latin orbs, orbis meaning "globe, world."[65]

An ode to discovery and exchange

[edit]

In the stories of the Atlas, the motifs of travel, discovery, and encounter frequently reappear.[77] Beyond inviting the reader on a metaphorical journey through the author's universe—where they create their mental map of the countries traversed, filled with uncertainties and multiple layers—[78]the characters portrayed are generally adventurers embarking on exploration (such as John Macselkirk on The Island of Giants, Cornélius towards The Indigo Islands, Zénon in The Land of the Lotus, Ortélius in Orbæ...) or in search of conquest (like Onésime Tiepolo in The Desert of Ultima).[79]

These characters often journey through dangerous, hostile, and hard-to-reach places (deserts, rugged mountains, virgin forests...), but these spaces are also fascinating and conducive to reflection.[80] The journey in these spaces often leads to regeneration and growth: for example, Nîrdan Pacha's journey through The Mandragore Mountains allows him to become better, reaching the peak of his physical and mental abilities,[81] learning the "true mysteries of the earth"[82] from a local sorcerer. This theme of the initiatory journey is found in many stories, such as Selva Island, where young people enter adulthood by fighting a flying tiger, or The Island of Orbæ, where crossing The Mist Rivers, the fog barrier surrounding the rich interior lands of the island, is made possible by the Guild of the Blind,[note 8] symbolizing access to knowledge through the teachings of initiates.[83]

At the end of their journey, the characters can recount what they have experienced and learned, often through a travel journal, such as that of the Native American Nohyk in The Land of the Yaléoutes, explorers Isaac des Bulan and Ulysse de Nalandès, travel companions of Anatole Brazadîm in The Indigo Islands, or the codex of Itilalmatulac in The Mountain of Esmeralda.[58] All of this connects the Atlas to the traditional travel narrative genre, which follows the usual mode of narration—historical narration in the sense of Benveniste, using third-person narration with alternating imperfect and past simple tenses—except for the autobiographical narrative in The Frosted Land.[70]

Through these travel narratives, Place is particularly interested in the idea of exchange, both economic and cultural, and spiritual.[84] Many of the territories traversed by the characters are mercantile interfaces (such as The Land of the Xing-Li, The Gulf of Candaâ),[85] but also, particularly at the borders (like The Land of the Houngalïls), places where different societies meet.[86] In this regard, the rich ethnographic imagination[87] described in the Atlas allows the author to confront many figures of foreigners and natives, adopting their perspectives in turn. The foreigner can be an explorer or conqueror driven by the thirst for adventure or the lure of profit, as well as a former slave trader introduced into an extraordinary kingdom, then sent home where he becomes a stranger to his people (Joao from The Land of the Red River) or a merchant who falls in love with a new land to the point of integrating into it and knowing it as well as the locals (Zénon d'Ambroisie from The Land of the Lotus).

On the other hand, the native might never have left his land (like Nangajiik from The Frosted Land or Kadelik from The Land of Korakar), might have left only to return, torn between his original people and the society he adopted (like Nohyk from The Land of the Yaléoutes, who was taken by the crew of a ship to their land and then returned home, struggling to find his place between both groups), or might have been exiled but returns secretly (like Ortélius from The Island of Orbæ and The Land of the Zizotls).[88] Thus, the boundary between foreigner and native is porous, and the foreigner can become a native, and vice versa. Some stories even juxtapose several perspectives on the same people, like in The Land of the Houngalïls, where Doctor Albinius is interested in the local customs while Princess Tahuana finds them barbaric.[55] Therefore, adopting multiple perspectives enriches the narrative and expresses an acceptance of the other in their difference:[89] the reader is invited to move beyond their dominant viewpoint and lose themselves in a labyrinth of peoples and cultures that must be apprehended in their diversity.[90]

This conception of cultural exchange thus generates a postcolonial discourse proclaiming the right to difference and the recognition of the other, as illustrated in the work by the recurring motif of the clash of cultures and the victory of traditional societies over the power of modernity.[91] While Place maintains a critical perspective throughout the Atlas, both on the flaws of Western civilization and on certain Indigenous customs (such as the cannibalism of the natives of The Island of Quinookta and the cruel religious tradition of the nomads in The Desert of Drums),[92] he frequently stages the defeat of imperialist Europe at the hands of Indigenous peoples:[91] the warriors of the Empire of the Five Cities defeat the conquistadors through dreams, the missionary who believes he has converted the people of Baïlabaïkal suddenly discovers he is the double of the old shaman, whom he must take on as his own,[93] and the settlers of The Land of the Yaléoutes fall victim to a glacier breaking off after having disrespected the old spiritual chief.[94]

The most significant episode in this regard is perhaps The Desert of Ultima, where the race organized by archetypical European powers to possess newly discovered lands—an explicit allegory of the colonial enterprise—is unexpectedly stopped by the sudden unleashing of natural elements. This brings the shiny, Vernian-like machines of mechanistic Western civilization to a state of totems, reclaimed by indigenous shamans and integrated into their mythology.[91]

This position marks a break in Place's work, which had begun with didactic books celebrating the history of explorers and the European conquest of the world (The Book of Navigators, The Book of Explorers, The Book of Merchants), before delivering the album The Last Giants a disenchanted view of the harmful effects of colonization.[95] With the Atlas, the author rebalances his values and firmly places himself under the sign of intercultural anthropology and the exchange between societies.[94]

A celebration of the powers of the imagination

[edit]

By drawing the reader into its fictional territories, the Atlas exalts the power of dreams and imagination.[95] The author develops a dreamy and fabulous world intended to spark wonder in the reader:[96] shamans who control the natural elements, such as those from Ultima and The Land of the Yaléoutes,[92] an ivory dolphin that comes to life upon contact with seawater in the eyes of young Ziyara of Candaâ, two-hearted sorcerers who guard The Mandragore Mountains, the eerie The Island of Quinookta that engulfs the crew of a whaling ship and transforms their vessel into a ghost ship,[96] as well as laughing toads and trumpet-wielding otters.[44]

However, the construction of this imaginary world is done with a concern for authenticity, creating a sense of reality through the authority of maps and encyclopedic double pages, which are meticulously illustrated with careful commentary.[97] Beneath this appearance of factuality, which contrasts with the imagination at play, Place seeks to plunge the reader into doubt and wonder,[98] inviting them to be enchanted,[99] as evidenced by the numerous confrontations he stages between rationalist Western thinking and the magical words of indigenous peoples, which often triumph. The slave trader Joao, for trying to leave the land of the King of kings, falls victim to a curse that robs him of speech, while the sovereign remains forever the "master of discourse." Similarly, the European settlers of The Land of the Yaléoutes, believing they can conquer the indigenous people through the sheer power of their firearms, see their ship destroyed by a falling glacier after threatening the old tribal sorcerer invoking the "word of the birds."[94]

This triumph of myth over reason is thus an invitation to set aside reductionist rationalism and be swept away by the shimmering mystery of the imagination. This exhortation is accompanied by a reflection on the very mechanisms that govern imagination and on humanity's tendency to recreate worlds.[100] The Atlas is permeated by a meditation on the hidden depths of the mind: for instance, The Mountain of Esmeralda portrays the victory of pre-Columbian warriors over the conquistadors, not through weapons, but because the latter were dreamt by the indigenous people.[101] For Place, imaginary worlds are thus more real than reality itself, and we are always the dream of another, as the missionary is concerning the old shaman of The Land of Baïlabaïkal.

This hermeneutic thesis, which views the universe in terms of the mind's disposition to seek profound meaning beyond appearances,[102] highlights humanity's tendency to extend its thought to the dimensions of reality.[103] Nothing is conceivable outside of one's conscious thought, as the mind tends toward solipsism.[104] Thus, according to the author, each person needs to tell themselves stories to exist, as reality is inseparable from its circumstances: hence the motif of the narrative, with the world not being what one sees but what one perceives, and even more so what one recounts.[105] The power of speech, an expression of the imaginary, is often evoked in the Atlas through characters gifted with eloquence, such as the old shaman Three-Stones-of-Stone, who reminds his people that "the sacred words of the fathers of your fathers are buried deep within your heart" and that "there would not be enough days in a whole year for me to make the inexhaustible source of them resurface here." There are also territories wholly dedicated to stories, like The Land of Xing-Li, which attracts travelers from afar to hear its tales.[106]

Imagination thus expresses itself through the power of words, but also through images and maps.[106] The power of the image, which expands the horizon and transports the viewer elsewhere, is evoked in the Atlas's narratives, for example, through the captivating painting of The Indigo Islands, contemplated by Cornélius in the Inn of Anatole Brazadîm,[note 9][106] and is directly applied in the illustrations, which complement the text[70] in a complementary rivalry. The images offer a shift in perspective (where the text favors an internal focus, the image provides an external viewpoint) and in scale (the smallness of the characters in the vast landscapes of the Atlas creates a sense of distance, in contrast to the text where the character is central).[107]

As for the map, which is at the heart of the work since it is explicitly presented as the "Atlas of the Geographers of Orbæ,"[2] it is described in various ways: as an instrument of domination, giving control over space by making it readable and governable (according to Nîrdan Pacha, the cartographer engineer of The Mandragore Mountains); as mere pieces of paper blinding the cartographer, cutting him off from true knowledge of the terrain (according to the mandarg sorcerer in the same story); or as the fertile soil of the world, opening the doors to dreams (according to Ortélius, the cosmographer of Orbæ).[108] For Ortélius, the map creates the world,[109] and indeed, from the reader's perspective, the large map at the opening of each story creates the world it contains.[110] Even more so, by reversing the logical process of representation in The Island of Orbæ, showing that his intervention on the Mother Map altered the degree of reality of the spaces depicted, the cosmographer advocates for a complete detachment from the real world and a surrender to creative imagination.[111]

This message is further reinforced by the very construction of the map-frontispieces, which are structured around a letter of the Latin alphabet, giving it not only its form but also the meaning of the narrative it introduces.[112] For example, the bicyclic geometry of the letter B is reflected in the almost homonymous two-part name of Baïlabaïkal, its twin lakes, the mismatched eyes of Trois-Cœurs-de-Pierre, and the symmetrical eyes of the missionary,[3] who then appears as his double.[93] Another example is the sacred dot on the letter I, which must always be well separated from its stem, becoming in The Indigo Islands, the Sacred Island, an extinct volcano that the inhabitants of the main island (the stem of the I) revere without being able to reach.[55]

Through this graphic daydreaming on letters,[3] and by the numerous citations and references he sprinkles throughout his stories, the author offers a reflection on imagination at work: his text is not nourished by a hypothetical reality but by other texts. This idea of intertextuality is symbolized by the character of the Palimpsest-Child, whose good eyes are the only ones able to decipher the Mother Map of Orbæ and discern the different layers of texts and images adorning it.[113] For Place, the imaginary is thus fueled by stories more than by perceptions: to imagine is not to reproduce one's reference world in the mental universe, but to superimpose one's imagination onto the world. The Atlas, by introducing the unknown into what could be considered an entirely known reality, truly allows for an expansion of reality through the power of imagination.[97]

References and influences

[edit]

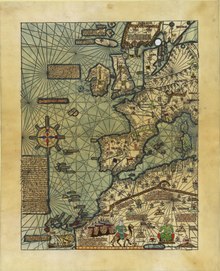

The Atlas is dotted with numerous references and citations drawn from our world,[107] especially from the history of cartography.[61] The map-frontispieces opening each chapter thus use the same cartographic vocabulary as other existing or historical maps.[114] For instance, the map of Nilandâr is in the tradition of ancient Persian miniatures, while the map of Ultima is inspired by 19th-century military topographic maps, and the map of Esmeralda references the 1519 Miller Atlas[58] and Mesoamerican codices.[61] The main map of the entire work, the Mother Map of Orbæ, is closest to 14th-century maps, particularly the aphylactic world map of Christian scholastic cartography,[note 10] such as the Ebstorf map, as well as portolan charts representing Europe and structured around maritime routes, like the Catalan Atlas by Abraham Cresques. The very idea of the Mother Map, conceived as an encyclopedia of the known world, is inspired by the Padrón Real, the secret map of the Spanish Crown where the latest discoveries in the New World were recorded: the divulgation of this precious document, kept at the Casa de Contratación in Seville, was punishable by death.[68]

In addition to the maps, the history of geography is also evoked through the very form of the Atlas, which recalls the very first geographical atlas, Mercator's Atlas of 1595.[note 11] This work was already conceived by its creator, Gerard Mercator, as an association of texts, illustrations, and maps divided into several chapters. Place takes the landscape format of his work from another 16th-century geographical work, Abraham Ortelius' Album amicorum, in which this cartographer gathered drawings and messages sent by his colleagues and friends across Europe between 1573 and 1579.[33] This inspiration is so significant that Ortelius, co-founder with Mercator of Germanic cartography[109] and author of the 1570 Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, the first printed cartographic collection (and therefore reproducible),[115] has his name taken for the main character of Orbæ.[109]

The immense Island of Orbæ itself represents Terra Australis, a vast continent that the Ancients believed extended to the south of the globe to balance the northern hemisphere's landmasses, which 16th-century cartographers like Ortelius included in their world maps.[59] While references to cartographic history abound, other elements of the Atlas also point to figures of explorers and adventurers, such as the naturalist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt[109] (whose illustrated publications, which meticulously document his travels and discoveries, echo the general structure of the triptych), the brothers Jacques and Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza (whose family name inspires that of Anatole Brazadîm in The Indigo Islands),[116] the sailor Alexander Selkirk[note 12] (whose name is evoked by John Macselkirk in The Island of Giants), the participants in the 1931-1932 "Yellow Cruise" automobile expedition (with the car race in Ultima offering an ironic reinterpretation),[91] and even Christopher Columbus, who, intending to sail to Asia, reached America (much like Ortelius, who, in The Land of the Zizotls, believes he's reaching The Indigo Islands, described as Eastern, but ends up in a seemingly Native American land).[39]

These geographical and cartographic influences are complemented by broader cultural references, ranging from religious (the Jade Emperor is borrowed from Taoist theology), architectural (the Old Bridge of the city on The Wallawa River evokes the Rialto Bridge in Venice),[63] to pictorial (the drawing of the "Dance of the Lost"[note 13] on the double-page spread at the end of The Land of the Amazons is adapted from a sketch by Hokusai).[75] Place also weaves numerous literary references, drawing from varied sources: while the general project of the work recalls other travel stories to imaginary lands, such as Voyage en Grande Garabagne by Henri Michaux, Le Mont Analogue by René Daumal,[44] or Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino,[54] the embedding of stories also evokes One Thousand and One Nights or The Manuscript Found in Saragossa by Jan Potocki.[105]

Specific allusions to other works appear within certain stories: The Mountain of Esmeralda is inspired by a Nahuatl text cited by Miguel León-Portilla, which tells the arrival of the conquistadors from the perspective of the indigenous peoples;[117] the expression "shell of humanity" used in a passage of The Frosted Land to describe the ice cave where the people of Nangajiik spend the polar night[note 14] echoes a line from Shakespeare's Hamlet,[note 15] where the metaphor of the shell symbolizes the human tendency to expand one's thought to the dimensions of reality;[102] the three main characters of The City of Vertigo—Izkadâr, Kholvino, and Buzodîn—are named after Ismaïl Kadaré, Italo Calvino, and Dino Buzzati, three authors whose works straddle the intersection of realism and the fantastic, much like Place's own;[39] and the epigraph of the Atlas on geography in Orbæ (see above) reprises a text that Jorge Luis Borges, master of South American magical realism, attributed to a fictional geographer from 1658.[note 16]

These references allow the author to introduce a distancing effect from the apparent realism of his work, enabling a reflection on the imagination at work, which immerses the reader in doubt and wonder.[98]

Sequel and derivative works

[edit]After the publication of the three volumes of The Atlas, Place declared in 2000 that he had "an enormous amount of unused material for this book," and he envisioned one day returning to the world of Orbæ in a different form.[118] This project came to fruition with the release in late 2011,[119] more than ten years after the first triptych,[120] of The Secret of Orbæ, a sequel to The Atlas comprising a box set containing two novels, a portfolio of landscapes, and a map of the world of Orbæ.[121] The two novels, titled The Voyage of Cornélius and The Voyage of Ziyara, follow the journeys of Ziyara (from The Gulf of Candaâ) and Cornélius (from The Indigo Islands) as they search for the cloud fabric and The Indigo Islands, eventually reaching the heart of The Island of Orbæ.[122] This sequel again earned its author a prize at the 2012 Bologna Children's Book Fair.

The Atlas also inspired a performance tale titled The Travels of Ziyara, interpreted by the company "Comme il vous plaira" starting in 2005,[123] as well as a landscaped garden called "From the World of Orbæ to the Indigo Islands," designed by Victorine Lalire, Guillaume Aimon, and Bruno Regnier for the sixteenth edition of the Royal Saltworks of Arc-et-Senans Garden Festival in 2016.[124]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The spelling "Orbæ" is that used in the printed albums; although the ligature æ mostly notes the sound [e] or [ɛ] in French, the author pronounces the name [ɔʁbae] ("Orbaé").

- ^ The Atlas was originally published in three volumes: Du Pays des Amazones aux Îles Indigo, 1996 (ISBN 2-203-14244-8), Du Pays de Jade à l'Île Quinookta, 1998 (ISBN 2-203-14264-2), and Du Pays des Amazones au Pays des Zizotls, 2000 (ISBN 2-203-14279-0). In 2015, it was reissued as a two-volume set (ISBN 978-2-203-03004-6).

- ^ Format 26 × 22

- ^ "The sunbirds are fed honey cakes in a circular courtyard at midday, in full sunlight. The rest of the time, they are kept out of the sunlight. Released into the wild, they fly to wherever the sun will shine brightest." Place 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Only the first volume was translated into English in 1999. Produced by Aubrey Lawrence, the translation is somewhat clumsy in breaking the link between the letters associated with certain territories and their names: Les Pays des Frissons thus becomes The Land of Shivers, with no connection to the letter F with which it is associated.

- ^ This translation, by Marie Luise Knott, preserves the correspondence between letters and country names.

- ^ These three poles are reminiscent of the tripartite functions that structure human activity in Indo-European societies, according to Georges Dumézil: the priestly function (cultural, Orbæ), the warrior function (political, Jade country) and the productive function (economic, Candaâ).

- ^ "Only the blind [...] walk with an even and sure step through the night of darkness or fog, so they alone have the power and right to guide expeditions across the Rivers of Mist, and it is in their hands that the rope of life that links each man to the one before him and the one after him must be placed."

- ^ "Despite its small size, the painting seemed to open onto a prodigiously expanded horizon. Cornelius could almost feel the breeze blowing from the mountain's summit, which he could not take his eyes off. He searched in his merchant's vocabulary for words to express his emotion. 'It's as if,' he stammered, 'it's as if...' 'Like an open window in the wall, don't you think?' said the innkeeper behind him, amused by his bewilderment."

- ^ An aphylactic map takes neither the size nor the shape of continents into account: this is notably the case of the world maps of the medieval West, which represent the world as described in the Bible.

- ^ From its original name, Atlas sive cosmographicæ meditationes de fabrica mundi et fabricati figura ("Atlas, or cosmographic meditations on the formation of the world and the world thus formed").

- ^ A source of inspiration for Daniel Defoe and his Robinson Crusoe.

- ^ "Sometimes, young men would venture out to meet the beautiful horsewomen. [...] The fierce Amazons would flee as soon as they saw the intruders. [...] They had to turn back. They returned to swell the ranks of the "Lost", their eyes lost in the distance and their hearts orphaned. [...] The Lost Ones would improvise dances in the sunlight, their eyes upside down and their lips foaming."

- ^ "We set off into the Big Sleep, the ice cliff detached from the glacier to begin a slow drift around the pack ice, our shell of humanity suspended between sea and sky merged in the same half-light, and the stars watched over our tangled dreams."

- ^ "O God! I could be locked up in a nutshell, and look at myself as the king of infinite space, if I didn't have bad dreams."

- ^ "In this empire, the Art of Cartography was pushed to such Perfection that the Map of a single Province occupied an entire city, and the Map of the Empire an entire Province. In time, these Excessive Maps ceased to give satisfaction, and the Colleges of Cartographers drew up a Map of the Empire, which had the Format of the Empire and coincided with it, point by point. Less keen on the study of cartography, later generations found this dilated map useless and, not without impiety, abandoned it to the inclemency of the Sun and Winters. In the deserts of the West, ruins of the Map remain. Animals and beggars inhabit them. All over the country, there is no longer any trace of the Geographic Disciplines."

References

[edit]- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, §1)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 14)

- ^ a b c Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 3)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 118)

- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 7)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 117)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 11-23)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 25-39)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 41-51)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 53-65)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 67-77)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 79-93)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 95-109)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 111-125)

- ^ Place (1996, p. 127-139)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 9-25)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 27-39)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 41-53)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 55-73)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 75-89)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 91-103)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 105-123)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 125-139)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 9-25)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 27-37)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 39-53)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 55-65)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 67-85)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 87-99)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 101-111)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 113-127)

- ^ Place (2000, p. 129-141)

- ^ a b c d e Meunier (2015, sec. 1. 1)

- ^ Place & Meunier (2013, note 3)

- ^ Bazin (2012, § 8)

- ^ Meunier (2015, introduction)

- ^ a b Place & Meunier (2013, § 12)

- ^ a b c d e Place (2017, p. 50)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Place a son atlas". Citrouille. November 22, 2000. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- ^ Place & Meunier (2013, § 14)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 2)

- ^ Place & Meunier (2013, § 17-19)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 79)

- ^ a b c d Barrot, Olivier (October 14, 1996). "François Place: Du Pays des Amazones aux Îles Indigo". ina.fr. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Bon, François (1996). "D'un atlas et ses fictions". Le Tiers Livre. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Pullman, Philip (March 28, 2000). "More than real". The Guardian. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ Leinkauf, Simone (March 2, 2001). "Phantastische Reisen: Der Kopf ist mein Fesselballon". Der Tagesspiegel. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Caravias, Christine (April 2008). "L'accueil enthousiaste des auteurs français à la Foire du livre de Taipei". bief.org. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "François Place, auteur et illustrateur" (PDF). francois-place.fr. 2015. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ BnF (2014, p. 21-22)

- ^ "Phantastische Reisen". jugendliteratur.org. 1998. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- ^ BnF (2014, p. 31-32)

- ^ "L'Atlas Imaginaire de François Place". etonnants-voyageurs.com. 1999. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 2)

- ^ a b c d O'Sullivan (2017, p. 25)

- ^ Meunier (2015, sec. 1. 3)

- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 8)

- ^ a b c Meunier (2015, sec. 3. 2)

- ^ a b Meunier (2015, sec. 3)

- ^ a b c Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 9)

- ^ a b c Meunier (2015, sec. 2. 2)

- ^ a b c Meunier (2015, sec. 3. 2)

- ^ a b Meunier (2014, p. 104)

- ^ Meunier (2015, sec. 1. 2)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 4-5)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 5)

- ^ Thémines (2012, sec. 2)

- ^ a b Meunier (2015, sec. 3.1)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 6)

- ^ a b c Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 14)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 16)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 3)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 4)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 4)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 5)

- ^ Meunier (2015, sec. 2. 2)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, p. 14)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 10)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 11)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 331)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 353)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, p. 12)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 360)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 364)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 328-329)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 365)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 17-18)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 18)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 18,20)

- ^ Bazin (2012, § 21)

- ^ a b c d Bazin (2012, § 23)

- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 19)

- ^ a b Bazin (2012, § 22)

- ^ a b c Bazin (2012, § 24)

- ^ a b Bazin (2012, § 21, 24)

- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 13)

- ^ a b Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 25)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 17-18)

- ^ Bazin (2012, § 25)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 10-11)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 8-9)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 9)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 9-10)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 10)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 11)

- ^ a b c Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 21)

- ^ a b Bazin (2011, p. 17)

- ^ Barjolle & Barjolle (2001, § 22-24)

- ^ a b c d Meunier (2014, p. 14)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 15)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 15)

- ^ Bazin (2011, p. 16)

- ^ Place (1998, p. 100)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 218)

- ^ Place (2017, p. 52)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 78)

- ^ Place (2017, p. 54-55)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 77)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 76)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 77)

- ^ Meunier (2014, p. 203)

- ^ Delbrassine (2012, p. 76-77)

- ^ BnF (2014, p. 29)

- ^ Fonteny, Elsa (June 27, 2016). "La création d'un jardin de A à Z". festivaldesjardins.eu. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barjolle, Mathilde; Barjolle, Éric (2001). "À la découverte de l'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ de François Place". Le Français aujourd'hui (133): 121–128. ISSN 0184-7732.

- Bazin, Laurent (2011). "Un univers dans une coquille de noix: pulsion microcosmique et topographie de l'imagination dans L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ de François Place". Publije. 2: 14–50. ISSN 2108-7121.

- Bazin, Laurent (2012). "De la prise de pouvoir à la prise de conscience: construction et déconstruction de l'idéologie coloniale dans l'œuvre illustrée de François Place". Strenæ. 3. eISSN 2109-9081.

- BnF, International Board on Books for Young People (2014). "François Place, Illustrator" (PDF). Dossier François Place.

- Delbrassine, Daniel (2012). "Le Secret d'Orbæ, de François Place". Lectures. 176: 76–78. ISSN 0251-7388.

- Meunier, Christophe (2014). "Quand les albums parlent d'Espace: Espaces et spatialités dans les albums pour enfants". ENS Lyon.

- Meunier, Christophe (July 29, 2015). "L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbae by François Place: The cartographic eye as poetics of the discovery of geography". Map's in Children's Literature. Bergen, Norway.

- O'Sullivan, Emer (June 2017). "Imagined Geography: Strange Places and People in Children's Literature" (PDF). The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture. 10 (2). ISSN 2077-1290.

- Place, François (1996). Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ. Vol. 1: Du Pays des Amazones aux Îles Indigo. France: Casterman-Gallimard. ISBN 2-203-14244-8.

- Place, François (1998). Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ. Vol. 2: Du Pays de Jade à l'Île Quinookta. Tournai/Paris: Casterman-Gallimard. ISBN 2-203-14264-2.

- Place, François (2000). Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ. Vol. 3: De la Rivière Rouge au Pays des Zizotls. Tournai/Paris: Casterman-Gallimard. ISBN 2-203-14279-0.

- Place, François; Meunier, Christophe (January 23, 2013). "Entretien avec François Place". Hypotheses. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Place, François (May 23, 2017). "Dans l'atelier de l'Atlas: genèse et création de l'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ" (PDF). Si loin, si proche: voyages imaginaires en littérature de jeunesse et alentour. Valenciennes: 47–58.

- Thémines, Jean-François (2012). "Parcours de petit géographe à partir de l'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ". L'Atelier du Grand Tétras: 153-163. ISBN 978-2911648526.

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- Authority notices: VIAF BnF WorldCat

- L'Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ. casterman.com. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Atlas des géographes d'Orbæ. francois-place.fr, François Place's personal website. Retrieved May 28, 2020.