Assyrian lion weights

| Assyrian lion weights | |

|---|---|

Three of the lion weights in the British Museum. The table below lists all the known lion and duck weights from Nimrud as of the late 19th century. | |

| |

| Material | Bronze |

| Writing | Phoenician language and cuneiform |

| Created | c. 800–700 BC |

| Discovered | 1845–51 |

| Present location | British Museum |

| Identification | ME 91220 |

The Assyrian lion weights are a group of bronze statues of lions, discovered in archaeological excavations in or adjacent to ancient Assyria.

The first published, and the most notable, are a group of sixteen bronze Mesopotamian weights found at Nimrud in the late 1840s and now in the British Museum.[1] They are considered to date from the 8th century BCE, with bilingual inscriptions in both cuneiform and Phoenician characters; the latter inscriptions are known as CIS II 1-14.

Nimrud weights

[edit]The Nimrud weights date from the 8th century BCE and have bilingual inscriptions in both cuneiform and Phoenician characters. The Phoenician inscriptions are epigraphically from the same period as the Mesha Stele.[2][3] They are one of the most important groups of artifacts evidencing the "Aramaic" form of the Phoenician script.[4] At the time of their discovery, they were the oldest Phoenician-style inscription that had been discovered.[5]

The weights were discovered by Austen Henry Layard in his earliest excavations at Nimrud (1845–51). A pair of lamassu were found at a gateway, one of which had fallen against the other and had broken into several pieces. After lifting the statue, Layard's team discovered under it sixteen lion weights.[6] The artefacts were first deciphered by Edwin Norris, who confirmed that they had originally been used as weights.[7]

The set form a regular series diminishing in size from 30 cm to 2 cm in length. The larger weights have handles cast on to the bodies, and the smaller have rings attached to them. The group of weights also included stone weights in the shape of ducks. The weights represent the earliest known uncontested example of the Aramaic numeral system.[8] Eight of the lions are represented with the only known inscriptions from the short reign of Shalmaneser V.[9] Other similar bronze lion weights were excavated at Abydos in western Turkey (also in the British Museum[10]) and the Iranian site of Susa by the French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan (now in the Louvre in Paris).[11]

There are two known systems of weights and measures from the ancient Middle East. One system was based on a weight called the mina which could be broken down into sixty smaller weights called shekels. These lion weights, however, come from a different system which was based on the heavy mina which weighed about a kilogram. This system was still being used in the Persian period and is thought to have been used for weighing metals.

The Lion weights were catalogued as CIS II 1-14, making them the first Aramaic inscription in the monumental Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum[12]

Gallery

[edit]-

1864 sketch of a Lion weight

-

Close up

-

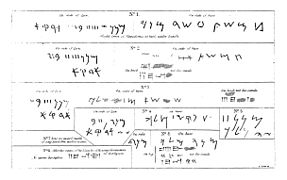

1856 sketch of the inscriptions from Lions 1-8

-

1856 sketch of the inscriptions from Lions 9-15 and Ducks 1-5

-

The Lion weights in the CIS

Abydos weight

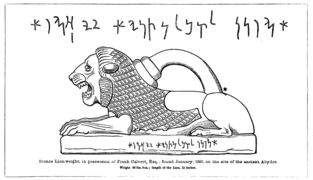

[edit]The second discovery of a lion weight was in Abydos (modern Turkey), dated to the 5th century BCE.[13][14] It is currently in the British Museum, with ID number E32625.

It contains an Aramaic inscription known as KAI 263 or CIS II 108.

-

Contemporary picture of BM lion weight from Abydos

-

Close up

-

Calvert 1860 sketch

Susa weight

[edit]A bronze lion weight discovered in 1901 at the Palace of Darius in Susa, dated to the 5th century BCE, is now in the Louvre with ID number Sb 2718.[15] It is not inscribed.

-

Bronze lion weight from the Palace of Darius in Susa, Louvre, 5th century BC

-

1905 photographs

Khorsabad weight

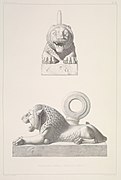

[edit]A similar discovery was made by Paul-Émile Botta in the 1840s at Khorsabad. It is currently in the Louvre, under ID number AO 20116.[16] It measures 29 cm high by 41 cm long, and is not inscribed.[16]

Despite the signifiant similarities to the other lions, Botta considered it was part of a door system, not a weight.[17][16] Botta wrote in his Monument De Ninive:[18]

Celte petite statue, comme je l'ai déjà dit, a été trouvée scellée sur une dalle qui pavait l'enfoncement formé par la saillie du taureau et du massif du côté droit de la porte F. Il y en a eu de semblables nonseulement de l'autre côté de cette porte, mais encore à tontes les grandes entrées du monument, car on retrouve les dales sur lesquelles elles étaient fixées; mais celle-ci est la seule qui n'ait pas disparu, et rien ne prouve mieux avec quelle avidité on a, lors de la destruction des édifices, enlevé tout ce qui avait quelque valeur. Ce lion est représenté couché, les pattes antérieures en avant, sur une base carrée audessous de laquelle est une forte tige conique qui pénétrait dans un trou du pavé. La statue est massive, et fondue d'une seule pièce avec la plinthe et l'anneau qui s'élève au milieu du dos. Elle a quarante-deux centimètres de long.

-

At the Louvre

-

At the Louvre

-

Botta 1850 sketch

See also

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Edwin Norris (1856), On the Assyrian and Babylonian Weights, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Volume 16 (editio princeps)

- Frederic Madden (1864), History of Jewish coinage, and of money in the Old and New Testament, B. Quaritch

- Fales, Frederick Mario (1995), Assyro-Aramaica : the Assyrian lion-weights, in Immigration and Emigration within the Ancient Near East, pages 33–55; editor: Festschrift E. Lipinski, Peeters

- British Museum description

References

[edit]- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ The Alphabet: An Account of the Origin and Development of Letters, Kegan Paul, Trench, 1883, Isaac Taylor, page 133, "The lion weights from Nineveh, which bear the names of Assyrian kings who reigned during the second half of the 8th century, an engraved scarab found beneath the foundation of the palace of Sargon at Khorsabad, and the bronze vessel dedicated to the temple of Baal-Lebanon, which bears the name of Hiram, king of the Sidonians, are epigraphically of the same age, or nearly so, as the inscription of Mesha"

- ^ Norris, 1856, p.215

- ^ Epigraphic West Semitic Scripts, 2006, Elsevier, Christopher Rollston, p.503, quote: "Some of the most important evidence for the Aramaic cursive script series are the Hamat bricks, the Lion-Weights from Nineveh, and the Nimrud ostracon (all dating to the 8th century)."

- ^ Henry Rawlinson (1865), Bilingual Readings: Cuneiform and Phœnician. Notes on Some Tablets in the British Museum, Containing Bilingual Legends (Assyrian and Phœnician), p.243, "Before concluding my notes on these tablet and seal legends, I would observe that they are among the most ancient specimens that we possess of Phoenician writing. I should select as the earliest specimens of all, the legends on the larger Lion Weights in the British Museum, one of which is clearly dated from the reign of Tiglath Pileser II. (b.c. 744-726). The other weights bear the royal names of Shalmaneser, Sargon, and Sennacherib."

- ^ Layard, Nineveh and its Remains, Murray, 1849, p.46-47: "I lifted the body with difficulty; and discovered under it sixteen copper lions, of admirable execution, forming a regular series, diminishing in size from the largest, which was above one foot in length, to the smallest, which scarcely exceeded an inch. A ring attached to the back of each, gave them the appearance of weights. In the same place were the fragments of an earthen vase, on which were represented two figures, with the wings and claws of a bird, the breasts of a woman, and the tail of a scorpion."

- ^ Madden, 1864, p.249

- ^ Numerical Notation: A Comparative History, CUP, 2010, Stephen Chrisomalis, page 71, ISBN 9781139485333

- ^ The Oxford Guide to People & Places of the Bible, p.285, Bruce Manning Metzger, Michael D. Coogan, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 9780195176100

- ^ British Museum collection

- ^ Louvre Collection

- ^ CIS II 1, p.1-2: "Anno 1853, clarissimus vir Layard, quum Ninives ruinas effoderet, in loco dicto Nimrud seriem sexdecim aeneorum exagiorum in lucem eruit, quæ in fundamentis assyriaci palatii, sub colossica statua monstri alati, corpore taurino et capite humano, subjecta erant (Layard, Nineveh and its remains, I, 128). Locus ubi reperta sunt nos docet exagia ista sacro quodam ritu in terram deposita esse, unde induci potest ea, legitima auctoritate exacta, in eodem usu apud Assyrios fuisse quo apud nos pondera dicta etalons. In speciem leonis ficta sunt, in quadrata basi recubantis et annulum tergo infixum ferentis. Unius exagii (cf. n um 2) imaginem, sole expressam, in tabula I reperies, et ab ea omnium leonum formam discere poteris. Figurarum sive lateribus sive basi incisi sunt tituli, assyriis vel aramaicis litteris conscripti, quibus uniuscujusque leonis pondus, sæpe etiam regnantis principis nomen docemur. Nomina assyriorum regum Salmanasar, Sargon et Sanherib ita leguntur, qui imperium ab anno ante J. C. circiter 727 usque ad annum 681 obtinuerunt. Quamvis aeris pondus, per tantum temporis spatium terra obruti, diversis modis mutatum sit, tamen a viris rei ponderalis peritis, qui titulos ponderaque contulerunt, demonstratum est leones duabus seriebus adscribendos esse, quarum una ab altera duplici pondere distinguitur. Sic constat assyrium talentum in sexaginta minas leves seu simplices, aut in triginta minas graves seu duplices divisum esse : mina ipsa in sexaginta drachmas dividebatur. Aramaici tituli de quibus agemus minam ... et drachmam ... siclum vocant. Pondera, auctore Oppert, qui novissime de his docte scripsit, gallicis grammatibus plus minus, ut sequitur, exprimi poasunt..."

- ^ Mitchell, T. C. “The Bronze Lion Weight from Abydos.” Iran, vol. 11, 1973, pp. 173–75. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4300493. Accessed 26 Jul. 2022.

- ^ Calvert, Frank (1860). "On a Bronze Weight Found on the Site of the Hellespontic Abydos". The Archaeological Journal. Longman: 199–200.

- ^ Georges Lampre, 1905, La Représentation du lion à Suse, Mémoires de la Délégation scientifique en Perse, VIII

- ^ a b c Edmond Pottier, Musée du Louvre: catalogue des Antiquités assyriennes, Paris, Musées nationaux, 1924, Disponible sur: n° 143: "Le lion de Khorsabad doit, en effet, avoir eu, d'après les circonstances de la découverte, une autre destination que celle d'un poids. Botta imaginait, parce qu'il y avait un autre anneau de bronze scellé au-dessus du lion dans le mur (voir notre n° 178), qu'une chaîne réunissait les deux anneaux et qu'on avait ainsi l'impression de lions de bronze enchaînés devant les murailles, comme des gardiens."

- ^ de Longpérier, Adrien (1854). Notice des antiquités assyriennes, babyloniennes, perses, hébraiques exposées dans les galeries du Musée du Louvre (in French). Vinchon. p. 50 (number 211). Retrieved 2022-07-26.

Cette admirable figure, un des plus beaux ouvrages que l'antiquité nous ait légués, paraît n'avoir eu d'autre destination que de servir de base et de décoration à l'anneau qu'il supporte, anneau auquel on attachait probablement l'extrémité d'une corde à l'aide de laquelle on hissait un voile au-dessus de la porte. Ce lion n'était pas mobile; à la partie inférieure existe un goujon de scellement. Il ne doit donc pas être confondu avec d'autres lions de bronze trouvés à Nimroud et sur lesquels on voit des inscriptions en caractères cunéiformes et en caractères phéniciens. On pense que ces monuments ont servi comme poids. Quant au lion de Khorsabad, il appartenait bien certainement au système général des portes; car à chacune d'elles on a retrouvé les pierres de scellement où des figures pareilles avaient été fixées.

- ^ Botta, P.E.; Flandin, E.N. (1850). Monument De Ninive Découvert Et Décrit. Imprimerie nationale. Retrieved 2022-07-26.