Central Asian art

| History of art |

|---|

Central Asian art is visual art created in Central Asia, in areas corresponding to modern Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and parts of modern Mongolia, China and Russia.[3][4] The art of ancient and medieval Central Asia reflects the rich history of this vast area, home to a huge variety of peoples, religions and ways of life. The artistic remains of the region show a remarkable combinations of influences that exemplify the multicultural nature of Central Asian society. The Silk Road transmission of art, Scythian art, Greco-Buddhist art, Serindian art and more recently Persianate culture, are all part of this complicated history.

From the late second millennium BC until very recently, the grasslands of Central Asia – stretching from the Caspian Sea to central China and from southern Russia to northern India – have been home to migrating herders who practised mixed economies on the margins of sedentary societies. The prehistoric 'animal style' art of these pastoral nomads not only demonstrates their zoomorphic mythologies and shamanic traditions but also their fluidity in incorporating the symbols of sedentary society into their own artworks.

Central Asia has always been a crossroads of cultural exchange, the hub of the so-called Silk Road – that complex system of trade routes stretching from China to the Mediterranean. Already in the Bronze Age (3rd and 2nd millennium BC), growing settlements formed part of an extensive network of trade linking Central Asia to the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia and Egypt.[5]

The arts of recent centuries are mainly influenced by Islamic art, but the varied earlier cultures were influenced by the art of China, Persia and Greece, as well as the Animal style that developed among the nomadic peoples of the steppes.[4] [6]

Upper Paleolithic

[edit]

The first modern human occupation in the difficult climates of North and Central Asia is dated to circa 40,000 ago, with the early Yana culture of northern Siberia dated to circa 31,000 BCE. By around 21,000 BCE, two main cultures developed: the Mal'ta culture and slightly later the Afontova Gora-Oshurkovo culture.[7]

The Mal'ta culture culture, centered around at Mal'ta, at the Angara River, near Lake Baikal in Irkutsk Oblast, Southern Siberia, and located at the northeastern periphery of Central Asia, created some of the first works of art in the Upper Paleolithic period, with objects such as the Venus figurines of Mal'ta. These figures consist most often of mammoth ivory. The figures are about 23,000 years old and stem from the Gravettian. Most of these statuettes show stylized clothes. Quite often the face is depicted.[8] The tradition of Upper Paleolithic portable statuettes being almost exclusively European, it has been suggested that Mal'ta had some kind of cultural and cultic connection with Europe during that time period, but this remains unsettled.[7][9]

Bronze Age

[edit]The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC, also known as the "Oxus civilization") is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age archaeological culture of Central Asia, dated to c. 2200–1700 BC, located in present-day eastern Turkmenistan, northern Afghanistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (known to the ancient Greeks as the Oxus River), an area covering ancient Bactria. Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Bactria was the Greek name for Old Persian Bāxtriš (from native *Bāxçiš)[10] (named for its capital Bactra, modern Balkh), in what is now northern Afghanistan, and Margiana was the Greek name for the Persian satrapy of Margu, the capital of which was Merv, in today's Turkmenistan.

Fertility goddesses, named "Bactrian princesses", made from limestone, chlorite and clay reflect agrarian Bronze Age society, while the extensive corpus of metal objects point to a sophisticated tradition of metalworking.[11] Wearing large stylised dresses, as well as headdresses that merge with the hair, "Bactrian princesses" embody the ranking goddess, character of the central Asian mythology that plays a regulatory role, pacifying the untamed forces.[citation needed]

-

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; between 3rd millennium and 2nd millennium BC; chlorite mineral group (dress and headdresses) and limestone (face and neck); height: 17.3 cm, width: 16.1 cm; Louvre

-

Ancient bowl with animals, Bactria, 3rd–2nd millennium BC.

-

Axe with eagle-headed demon & animals; late 3rd millennium-early 2nd millennium BC; gilt silver; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Camel figurine; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; copper alloy; 8.89 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

-

Handled weight; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; chlorite; 25.08 x 19.69 x 4.45 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; 2500–1500; chlorite (dress and headdresses) and limestone (head, hands and a leg); height: 13.33 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA)

-

Beaker with birds on the rim; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; electrum; height: 12 cm, width: 13.3 cm, depth: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Scythian cultures

[edit]Pazyrik culture (6th–3rd century BC)

[edit]

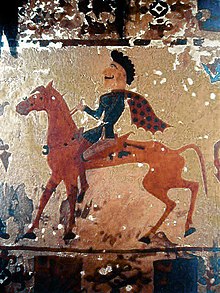

The Pazyryk culture is a Scythian[12] nomadic Iron Age archaeological culture (of Iranian origin; c. 6th to 3rd centuries BC) identified by excavated artifacts and mummified humans found in the Siberian permafrost, in the Altay Mountains, Kazakhstan and nearby Mongolia. The mummies are buried in long barrows (or kurgans) similar to the tomb mounds of Scythian culture in Ukraine. The type site are the Pazyryk burials of the Ukok Plateau.[13] Many artifacts and human remains have been found at this location, including the Siberian Ice Princess, indicating a flourishing culture at this location that benefited from the many trade routes and caravans of merchants passing through the area.[14] The Pazyryk are considered to have had a war-like life.[15]

Other kurgan cemeteries associated with the culture include those of Bashadar, Tuekta, Ulandryk, Polosmak and Berel. There are so far no known sites of settlements associated with the burials, suggesting a purely nomadic lifestyle.

The remarkable textiles recovered from the Pazyryk burials include the oldest woollen knotted-pile carpet known, the oldest embroidered Chinese silk, and two pieces of woven Persian fabric (State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg). Red and ochre predominate in the carpet, the main design of which is of riders, stags, and griffins. Many of the Pazyryk felt hangings, saddlecloths, and cushions were covered with elaborate designs executed in appliqué feltwork, dyed furs, and embroidery. Of exceptional interest are those with animal and human figural compositions, the most notable of which are the repeat design of an investiture scene on a felt hanging and that of a semi-human, semi-bird creature on another (both in the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg). Clothing, whether of felt, leather, or fur, was also lavishly ornamented.

Horse reins either had animal designs cut out on them or were studded with wooden ones covered in gold foil. Their tail sheaths were ornamented, as were their headpieces and breast pieces. Some horses were provided with leather or felt masks made to resemble animals, with stag antlers or rams' horns often incorporated in them. Many of the trappings took the form of iron, bronze, and gilt wood animal motifs either applied or suspended from them; and bits had animal-shaped terminal ornaments. Altai-Sayan animals frequently display muscles delineated with dot and comma markings, a formal convention that may have derived from appliqué needlework. Such markings are sometimes included in Assyrian, Achaemenian, and even Urartian animal representations of the ancient Middle East. Roundels containing a dot serve the same purpose on the stag and other animal renderings executed by contemporary Śaka metalworkers. Animal processions of the Assyro-Achaemenian type also appealed to many Central Asian tribesmen and are featured in their arts.

Certain geometric designs and sun symbols, such as the circle and rosette, recur at Pazyryk but are completely outnumbered by animal motifs. The stag and its relatives figure as prominently as in Altai-Sayan. Combat scenes between carnivores and herbivores are exceedingly numerous in Pazyryk work; the Pazyryk beasts are locked in such bitter fights that the victim's hindquarters become inverted.[16]

-

Pazyryk carpet

-

Pazyryk saddlecloth.

Art of the steppes

[edit]Tribes of Europoid type appear to have been active in Mongolia and Southern Siberia from ancient times. They were in contact with China and were often described for their foreign features.[18]

-

Bronze plaque of a man of the Ordos Plateau, later held by the Xiongnu. 3–1st century BC, British Museum. Otto Maenchen-Helfen notes that the statuette displays Caucasoid features.[19]

-

Belt Buckle, Mongolia or southern Siberia, 2nd–1st century BC.[20]

-

The Boar hunter, with characteristic Xiongnu horse trappings, Southern Siberia, 280–180 BC. Hermitage Museum.[22][23][24]

Sakas

[edit]

The art of the Saka was of a similar styles as other Iranian peoples of the steppes, which is referred to collectively as Scythian art.[26] [27]In 2001, the discovery of an undisturbed royal Scythian burial-barrow illustrated Scythian animal-style gold that lacks the direct influence of Greek styles. Forty-four pounds of gold weighed down the royal couple in this burial, discovered near Kyzyl, capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva.

Ancient influences from Central Asia became identifiable in China following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories from the 8th century BC. The Chinese adopted the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat), particularly the rectangular belt-plaques made of gold or bronze, and created their own versions in jade and steatite.[28][page needed]

Following their expulsion by the Yuezhi, some Saka may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China. Saka warriors could also have served as mercenaries for the various kingdoms of ancient China. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilisation of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.[29]

Saka influences have been identified as far as Korea and Japan. Various Korean artifacts, such as the royal crowns of the kingdom of Silla, are said to be of "Scythian" design.[30] Similar crowns, brought through contacts with the continent, can also be found in Kofun era Japan.[31]

-

"Kings with dragons", Tillia Tepe

-

Battle scenes on the Orlat plaques. 1st century AD.

-

Crown from Tomb VI of Tillya Tepe (female owner)

Achaemenid period

[edit]

Margiana and Bactria belonged to the Medes for a time, and were then annexed to the Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great in sixth century BC, forming the twelfth satrapy of Persia.[33][34]

Under Persian rule, many Greeks were deported to Bactria, so that their communities and language became common in the area. During the reign of Darius I, the inhabitants of the Greek city of Barca, in Cyrenaica, were deported to Bactria for refusing to surrender assassins.[35] In addition, Xerxes also settled the "Branchidae" in Bactria; they were the descendants of Greek priests who had once lived near Didyma (western Asia Minor) and betrayed the temple to him.[36] Herodotus also records a Persian commander threatening to enslave daughters of the revolting Ionians and send them to Bactria.[37] Persia subsequently conscripted Greek men from these settlements in Bactria into their military, as did Alexander later.[38]

Hellenistic and Greco-Bactrian art (265–145 BC)

[edit]The Greco-Bactrians ruled the southern part of Central Asia from the 3rd to the 2nd century BC, with their capital at Ai-Khanoum.[39][40][41]

The main known remains from this period are the ruins and artifacts of their city of Ai-Khanoum, a Greco-Bactrian city founded circa 280 BC which continued to flourish during the first 55 years of the Indo-Greek period until its destruction by nomadic invaders in 145 BC, and their coinage, which is often bilingual, combining Greek with the Indian Brahmi script or Kharoshthi.[42] Apart from Ai-Khanoum, Indo-Greek ruins have been positively identified in few cities such as Barikot or Taxila, with generally much fewer known artistic remains.[40][43]

Architecture in Bactria

[edit]

Numerous artefacts and structures were found, particularly in Ai-Khanoum, pointing to a high Hellenistic culture, combined with Eastern influences, starting from the 280–250 BC period.[44][45][46] Overall, Aï-Khanoum was an extremely important Greek city (1.5 sq kilometer), characteristic of the Seleucid Empire and then the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, remaining one of the major cities at the time when the Greek kings started to occupy parts of India, from 200 to 145 BC. It seems the city was destroyed, never to be rebuilt, about the time of the death of king Eucratides around 145 BC.[46]

Archaeological missions unearthed various structures, some of them perfectly Hellenistic, some other integrating elements of Persian architecture, including a citadel, a Classical theater, a huge palace in Greco-Bactrian architecture, somehow reminiscent of formal Persian palatial architecture, a gymnasium (100 × 100m), one of the largest of Antiquity, various temples, a mosaic representing the Macedonian sun, acanthus leaves and various animals (crabs, dolphins etc...), numerous remains of Classical Corinthian columns.[46] Many artifacts are dated to the 2nd century BC, which corresponds to the early Indo-Greek period.

-

Ai- Khanoum mosaic (central detail in color).

-

Architectural antefixae with Hellenistic "Flame palmette" design, Ai-Khanoum.

-

Sun dial within two sculpted lion feet.

-

Winged antefix, a type only known from Ai-Khanoum.

Sculpture

[edit]

Various sculptural fragments were also found at Ai-Khanoum, in a rather conventional, classical style, rather impervious to the Hellenizing innovations occurring at the same time in the Mediterranean world. Of special notice, a huge foot fragment in excellent Hellenistic style was recovered, which is estimated to have belonged to a 5–6 meter tall statue (which had to be seated to fit within the height of the columns supporting the Temple). Since the sandal of the foot fragment bears the symbolic depiction of Zeus' thunderbolt, the statue is thought to have been a smaller version of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia.[47][48]

Due to the lack of proper stones for sculptural work in the area of Ai-Khanoum, unbaked clay and stucco modeled on a wooden frame were often used, a technique which would become widespread in Central Asia and the East, especially in Buddhist art. In some cases, only the hands and feet would be made in marble.

In India, only a few Hellenistic sculptural remains have been found, mainly small items in the excavations of Sirkap.

-

Sculpture of an old man. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Close-up of the same statue.

-

Frieze of a naked man wearing a chlamys. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Hellenistic gargoyle. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Artefacts

[edit]

A variety of artefacts of Hellenistic style, often with Persian influence, were also excavated at Ai-Khanoum, such as a round medallion plate describing the goddess Cybele on a chariot, in front of a fire altar, and under a depiction of Helios, a fully preserved bronze statue of Herakles, various golden serpentine arm jewellery and earrings, a toilet tray representing a seated Aphrodite, a mold representing a bearded and diademed middle-aged man. Various artefacts of daily life are also clearly Hellenistic: sundials, ink wells, tableware. An almost life-sized dark green glass phallus with a small owl on the back side and other treasures are said to have been discovered at Ai-Khanoum, possibly along with a stone with an inscription, which was not recovered. The artefacts have now been returned to the Kabul Museum after several years in Switzerland by Paul Bucherer-Dietschi, Director of the Swiss Afghanistan Institute.[49]

-

Bronze Herakles statuette. Ai-Khanoum. 2nd century BC.

-

Bracelet with horned female busts. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

-

Stone recipients from Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

-

Imprint from a mold found in Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

Yuezhi and Kushan art

[edit]Some traces remain of the presence of the Kushans in the areas of Bactria and Sogdiana. Archaeological structures are known in Takht-I-Sangin, Surkh Kotal (a monumental temple), and in the palace of Khalchayan. Various sculptures and friezes are known, representing horse-riding archers, and, significantly, men with artificially deformed skulls, such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan (a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia).[50]

Khalchayan (1st century BC)

[edit]The art of Khalchayan of the end of the 2nd–1st century BC is probably one of the first known manifestations of Kushan art.[56] It is ultimately derived from Hellenistic art, and possibly from the art of the cities of Ai-Khanoum and Nysa.[56] At Khalchayan, rows of in-the-round terracotta statues showed Kushan princes in dignified attitudes, while some of the sculptural scenes are thought to depict the Kushans fighting against the Sakas.[57] The Yuezis are shown with a majestic demeanour, whereas the Sakas are typically represented with side-wiskers, displaying expressive and sometimes grotesque features.[57]

According to Benjamin Rowland, the styles and ethnic type visible in Kalchayan already anticipate the characteristics of the later Art of Gandhara and may even have been at the origin of its development.[56] Rowland particularly draws attention to the similarity of the ethnic types represented at Khalchayan and in the art of Gandhara, and also in the style of portraiture itself.[56] For example, Rowland find a great proximity between the famous head of a Yuezhi prince from Khalchayan, and the head of Gandharan Bodhisattvas, giving the example of the Gandharan head of a Bodhisattva in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[56] The similarity of the Gandhara Bodhisattva with the portrait of the Kushan ruler Heraios is also striking.[56] According to Rowland the Bactrian art of Khalchayan thus survived for several centuries through its influence in the art of Gandhara, thanks to the patronage of the Kushans.[56]

Bactria (1st–3rd century AD)

[edit]The Kushans apparently favoured royal portraiture, as can be seen in their coins and their dynastic sculptures.[58] A monumental sculpture of King Kanishka I has been found in Mathura in northern India, which is characterized by its frontality and martial stance, as he holds firmly his sword and a mace.[58] His heavy coat and riding boots are typically nomadic Central Asian, and are way too heavy for the warm climate of India.[58] His coat is decorated by hundreds of pearls, which probably symbolize his wealth.[58] His grandiose regnal title is inscribed in the Brahmi script: "The Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishka".[59][58]

As the Kushans progressively adapted to life in India, their dress progressively became lighter, and representation less frontal and more natural, although they retained characteristic elements of their nomadic dress, such as the trousers and boots, the heavy tunics, and heavy belts.

-

Early Kushan ruler Heraios (1–30 AD), from his coinage.

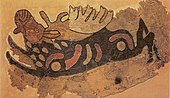

-

Figures in the embroidered carpets of the Noin-Ula burial site, made in Bactria and proposed to represent Yuezhis (1st century BC – 1st century AD).[60][61][62]

-

Kushan men in caftan and boots, at Fayaz Tepe

-

Buddhist mural in Kara Tepe, 2nd–4th century AD.

-

Buddhist pillar capital from Surkh Kotal, with central Buddha figure.

Kushano-Sasanian art (3rd–4th century AD)

[edit]The Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom (also called "Kushanshas" KΟÞANΟ ÞAΟ Koshano Shao in Bactrian[65]) is a historiographic term used by modern scholars[66] to refer to a branch of the Sasanian Persians who established their rule in Bactria and in northwestern Indian subcontinent (present day Pakistan) during the 3rd and 4th centuries AD at the expense of the declining Kushans. They captured the provinces of Sogdiana, Bactria and Gandhara from the Kushans in 225 AD.[67] The Kushano-Sassanids traded goods such as silverware and textiles depicting the Sassanid emperors engaged in hunting or administering justice. The example of Sassanid art was influential on Kushan art, and this influence remained active for several centuries in northwest South Asia.

-

Kushano-Sasanian footed cup with medallion, 3rd-4th century AD, Bactria, Metropolitan Museum of Art.[68]

-

Possible Kushano-Sasanian plate, excavated in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, 350–400 AD.[69] British Museum 124093.[70][71]

-

Terracotta head of a male figure, Kushano-Sasanian period, Gandhara region, 4th–5th century AD

Huns

[edit]The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. The nomadic nature of Hun society means that they have left very little in the archaeological record.[72] Archaeological finds have produced a large number of cauldrons that have since the work of Paul Reinecke in 1896 been identified as having been produced by the Huns.[73] Although typically described as "bronze cauldrons", the cauldrons are often made of copper, which is generally of poor quality.[74] Maenchen-Helfen lists 19 known finds of Hunnish cauldrons from all over Central and Eastern Europe and Western Siberia.[75] They come in various shapes, and are sometimes found together with vessels of various other origins.[76]

Both ancient sources and archaeological finds from graves confirm that the Huns wore elaborately decorated golden or gold-plated diadems.[77] Maenchen-Helfen lists a total of six known Hunnish diadems.[78] Hunnic women seem to have worn necklaces and bracelets of mostly imported beads of various materials as well.[79] The later common early medieval practice of decorating jewelry and weapons with gemstones appears to have originated with the Huns.[80] They are also known to have made small mirrors of an originally Chinese type, which often appear to have been intentionally broken when placed into a grave.[81]

Archaeological finds indicate that the Huns wore gold plaques as ornaments on their clothing, as well as imported glass beads.[82] Ammianus reports that they wore clothes made of linen or the furs of marmots and leggings of goatskin.[83]

-

A Hunnish cauldron

-

Detail of Hunnish gold and garnet bracelet, 5th century, Walters Art Museum

-

A Hunnish oval openwork fibula set with a carnelian and decorated with a geometric pattern of gold wire, 4th century, Walters Art Museum

Kidarites

[edit]

The Kidarites, or "Kidara Huns",[86] were a dynasty that ruled Bactria and adjoining parts of Central Asia and South Asia in the 4th and 5th centuries. The Kidarites belonged to a complex of peoples known collectively in India as the Huna, and in Europe as the Chionites (from the Iranian names Xwn/Xyon), and may even be considered as identical to the Chionites.[87] The 5th century Byzantine historian Priscus called them Kidarites Huns, or "Huns who are Kidarites".[88][89] The Huna/ Xionite tribes are often linked, albeit controversially, to the Huns who invaded Eastern Europe during a similar period. They are entirely different from the Hephthalites, who replaced them about a century later.[89]

-

Silver bowl, showing an Alchon horseman

-

Two Kidarite princes on the Hephthalite bowl

Hephthalite art (4th–6th century AD)

[edit]The Hephthalites (Bactrian: ηβοδαλο, romanized: Ebodalo),[95] sometimes called the "White Huns",[96][97] were a people who lived in Central Asia during the 5th to 8th centuries. They existed as an Empire, the "Imperial Hephthalites", and were militarily important from 450 AD, when they defeated the Kidarites, to 560 AD, date of their defeat to combined First Turkic Khaganate and Sasanian Empire forces.[98][99]

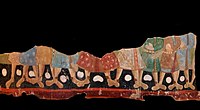

The Hepthalites appears in several mural paintings in the area of Tokharistan, especially in banquet scenes at Balalyk tepe and as donors to the Buddha in the ceiling painting of the 35-meter Buddha at the Buddhas of Bamiyan.[100] Several of the figures in these paintings have a characteristic appearance, with belted jackets with a unique lapel of their tunic being folded on the right side, a style which became popular under the Hephthalites,[101] the cropped hair, the hair accessories, their distinctive physionomy and their round beardless faces.[102][103] The figures at Bamiyan must represent the donors and potentates who supported the building of the monumental giant Buddha.[102] These remarkable paintings participate "to the artistic tradition of the Hephthalite ruling classes of Tukharistan".[100][104]

The paintings related to the Hephthalites have often been grouped under the appellation of "Tokharistan school of art",[105] or the "Hephthalite stage in the History of Central Asia Art".[106] The paintings of Tavka Kurgan, of very high quality, also belong to this school of art, and are closely related to other paintings of the Tokharistan school such as Balalyk tepe, in the depiction of clothes, and especially in the treatment of the faces.[107]

This "Hephthalite period" in art, with the caftans with a triangular collar folded on the right, the particular cropped hairstyle, the crowns with crescents, have been found in many of the areas historically occupied and ruled by the Hephthalites, in Sogdia, Bamiyan (modern Afghanistan), or in Kucha in the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). This points to a "political and cultural unification of Central Asia" with similar artistic styles and iconography, under the rule of the Hephthalites.[108]

-

The banquet scenes in the murals of Balalyk Tepe show the life of the Hephthalite ruling class of Tokharistan.[109][103][104][100]

-

Banquet scene, Balalyk Tepe

-

Probable Hephthalite royal couple in the murals of the Buddhas of Bamiyan circa 600 AD (the 38-meter Buddha they decorate is carbon dated to 544–595 AD).[110]

-

Stamp seal with a bearded figure in Sasanian dress, wearing the kulāf denoting nobility and officials; and a figure with radiate crown,[111] both with royal ribbons. Attributed to the Hephthalites,[112] and recently dated to the 5th–6th century AD.[113] Stamp seal (BM 119999), British Museum.

Buddhist art of Bamiyan

[edit]The Buddhist art of Bamiyan covers a period from the early centuries of the Common Era, culminating with the building of the Buddhas of Bamiyan in the 6th-century AD.[116] monumental statues of Gautama Buddha carved into the side of a cliff in the Bamyan valley of central Afghanistan, 130 kilometres (81 mi) northwest of Kabul at an elevation of 2,500 metres (8,200 ft). Carbon dating of the structural components of the Buddhas has determined that the smaller 38 m (125 ft) "Eastern Buddha" was built around 570 AD, and the larger 55 m (180 ft) "Western Buddha" was built around 618 AD.[110][115]

The statues represented a later evolution of the classic blended style of Gandhara art.[117] The statues consisted of the male Salsal ("light shines through the universe") and the (smaller) female Shamama ("Queen Mother"), as they were called by the locals.[118] The main bodies were hewn directly from the sandstone cliffs, but details were modeled in mud mixed with straw, coated with stucco. This coating, practically all of which wore away long ago, was painted to enhance the expressions of the faces, hands, and folds of the robes; the larger one was painted carmine red and the smaller one was painted multiple colors.[119] The lower parts of the statues' arms were constructed from the same mud-straw mix supported on wooden armatures. It is believed that the upper parts of their faces were made from great wooden masks or casts. The rows of holes that can be seen in photographs held wooden pegs that stabilized the outer stucco.

The Buddhas are surrounded by numerous caves and surfaces decorated with paintings.[120] It is thought that the period of florescence was from the 6th to 8th century AD, until the onset of Islamic invasions.[120] These works of art are considered as an artistic synthesis of Buddhist art and Gupta art from India, with influences from the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, as well as the country of Tokharistan.[120]

-

Buddha, Cave 404 in Bamiyan.

-

Sun-God Surya on his chariot

-

Western Buddha, Niche, ceiling, east section E1 and E2.[123]

Tarim Basin

[edit]

From the 3rd century AD, the Tarim Basin became a centre for the development of Buddhist art, and a major relay for the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism. Buddhist texts were translated into Chinese by Kuchean monks, the most famous of whom was Kumārajīva (344–412/5).[124][125]

Indian and Central Asian influences

[edit]Numerous Buddhist caves cover the northern side of the Tarim Basin, such as the Kizil Caves consisting in over 236 such temples. Their murals date from the 3rd to the 8th century.[126] The caves of Kizil are the earlier of their type in China, and their model was later adopted in the construction of Buddhist caves further east.[127] Other famous sites nearby are the Kizilgaha caves, the Kumtura Caves, Subashi Temple or the Simsim caves.[128][129]

In the Kizil Caves appear portraits of Royal families, composed of the King, Queen and young Prince. They are accompanied by monks, and men in caftan.[130]

Interaction with Chinese art

[edit]The influence of Chinese art started to appear in the eastern part of the Tarim Basin, as Buddhist art was spreading eastward. These Chinese characteristics appear in the art of the Bezeklik Caves or the Dunhuang Caves.

-

Details from Praṇidhi scene No. 5. Central Asian and Asian Buddhist monks.[133]

-

Bodhisattva leading a lady donor towards the Pure Lands. Painting on silk (Library Cave), Late Tang. Mogao Caves

-

Figure of Maitreya Buddha in cave 275 from Northern Liang (397–439), one of the earliest caves. The crossed ankle figure with a three-disk crown shows influence from Kushan art. Mogao Caves

Sogdian art

[edit]The Afrasiab paintings of the 6th to 7th centuries in Samarkand, Uzbekistan offer a rare surviving example of Sogdian art. The paintings, showing scenes of daily life and events such as the arrival of foreign ambassadors, are located within the ruins of aristocratic homes. It is unclear if any of these palatial residences served as the official palace of the rulers of Samarkand.[134] The oldest surviving Sogdian monumental wall murals date to the 5th century and are the Penjikent murals, Tajikistan.[135] In addition to revealing aspects of their social and political lives, Sogdian art has also been instrumental in aiding historians' understanding of their religious beliefs. For instance, it is clear that Buddhist Sogdians incorporated some of their own Iranian deities into their version of the Buddhist Pantheon. At Zhetysu, Sogdian gilded bronze plaques on a Buddhist temple show a pairing of a male and female deity with outstretched hands holding a miniature camel, a common non-Buddhist image similarly found in the paintings of Samarkand and Panjakent.[136]

-

Afrasyab Chinese Embassy (left), carrying silk and a string of silkworm cocoons, and Turkish delegates (right), recognizable by their long plaits.[137][138]

-

Rostam, with an elongated skull, Penjikent murals

-

The Anikova dish: a Nestorian Christian plate with decoration of a besieged Jericho, by Sogdian artists under Karluk dominion, Semirechye. 9th-10th century, derived form 8th century material related to Penjikent.[143][144][145]

Central Asian art in ancient China

[edit]From the 4th to the 6th centuries AD, the Northern dynasties (389–589 AD) of China, ruled by the nomadic Xianbei, engaged in trade with Central Asia, often through the intermediary of Sogdian traders. Northern Wei art came under influence of Indian and Central Asian traditions through the mean of these trade routes. This included the influence of Buddhism, which flourished under the Northern dynasties.[148] Numerous Central Asian works of art, especially decorated silverware and jewelry, have been found in the tombs of the Northern Wei, the Northern Qi or the Northern Zhou.[149][150][151]

Turkic art

[edit]The Gokturks destroyed the Rouran Khaganate and overran the Hephthalite Empire to became the main power in Central Asia from the time of the First Turkic Khaganate and the Western Turks, circa 560 to 742 AD. Several later Turkic-speaking empires would later develop, founded by unrelated tribes.

-

Silver artifacts from Khakassia, associated wjth the Yenisei Kyrgyz people.[155]

-

Warrior statue; 8th–10th century; from the Kosh-Agach region (Altai); Hermitage (Sankt Petersburg, Russia)

-

An early Turk Shahi ruler named Sri Ranasrikari "The Lord who brings excellence through war" (Brahmi script). In this realistic portrait, he wears the Turkic double-lapel caftan. Late 7th to early 8th century AD.[160][161][162]

Islamic Golden Age in Central Asia

[edit]The Muslim conquest of Transoxiana was the 7th and 8th century conquests, by Umayyad and Abbasid Arabs, of Transoxiana, the land between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers, a part of Central Asia that today includes all or parts of Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. This started a period of prosperity, from the 8th to the 14th century, known as the Islamic Golden Age, which also affected the arts of Central Asia.

Arab period (7–8th centuries)

[edit]Islamic art diffused in Central Asia with the rule of Umayyad and Abbasid Arabs. Buildings following Islamic standard were built throughout the land, such as the Abbasid mosque of Afrasiab in Samarkand circa 750–825 CE.[163]

-

Folio sheet from a Qur'an, found in the sanctuary of Katta Langar, south of Samarkand, first half of the 8th century.

-

Coran from Katta Langar, decorative band (detail)

Iranian Intermezzo (9–10th centuries)

[edit]Abbasid power finally waned, and local Iranian dynasties were established, creating an Iranian Intermezzo, blending Islamic art with Persian culture, during the 9th and 10th centuries. The Iranian dynasties corresponding to the Iranian Intermezzo are the Tahirids, Saffarids, Sajids, Samanids, Ziyarids, Buyids and Sallarids.[164]

Samanids (819–999)

[edit]Artistic florescence occurred especially during the period of the Samanid Empire (819–999). The empire was centred in Khorasan and Transoxiana; at its greatest extent encompassing modern-day Afghanistan, large parts of Iran, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, parts of Kazakhstan and Pakistan.

-

"Simurgh platter", from Iran, Samanids dynasty. 9th-10th century. Islamic Art Museum (Museum für Islamische Kunst), Berlin

Buyids (932–1062)

[edit]The Būyids, also an Iranian dynasty, became great patrons of art and architecture, as a way to enhance their prestige and to compensate for their humble origins. Through art, they endeavoured to present themselves as the heirs to the pre-Islamic tradition of kingship in Iran.[166]

-

Medallion of Buyid amir 'Adud al-Dawla (r.936–983).

-

Gold ewer of the Buyid Period, mentioning Buyid ruler Izz al-Dawla Bakhtiyar ibn Mu'izz al-Dawla, 966-977 CE, Iran.[167]

-

Buyid silk in pseudo-Sasanian style.

-

Rosewater bottle, Buyid art, early 12th century, Iran. Freer Gallery of Art.[168]

Turkic dynasties (9–13th centuries)

[edit]With the rise of Turkic dynasties in Central Asia, Persian art started to evolve to adapt to the tastes of the new Turkic ruling class: in paintings, the composition of narrative scenes remains unchanged, but nomadic clothing, physical traits and power symbols (such as the bow and arrow) are now depicted. From the mid-12th century, beauty standards too evolve, with round and serene faces with almond-shaped eyes becoming uniquitous in artistic representations.[169]

Kara-Khanid Khanate (840-1212)

[edit]

A palatial structure dating to the Kara-Khanid Khanate (840–1212) was recently discovered in Afrasiab, complete with numerous decorative paintings dating to circa 1200.[171] This period of artistic florescence would end in 1212, when the Kara-Khanids in Samarkand were conquered by the Kwarazmians. Soon however, Khwarezmia was invaded by the early Mongol Empire and its ruler Genghis Khan destroyed the once vibrant cities of Bukhara and Samarkand.[173] However, in 1370, Samarkand saw a revival as the capital of the Timurid Empire.[174]

-

Kara-Khanid bands of inscription with running animals, Afrasiab, circa 1200 CE.[175]

Ghaznavids (977–1186)

[edit]The Ghaznavid dynasty was a Persianate[178] Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin,[179][a][180] at their greatest extent ruling large parts of Iran, Afghanistan, much of Transoxiana and the northwest Indian subcontinent from 977 to 1186.[181]

-

Ghaznavid portrait of a characteristically Turkic individual, Palace of Lashkari Bazar.[182]

-

Ghaznavid sculpted architecture, marble, Ghazni, 12th century AD

-

Vessel with bull's head spout, Ghaznavid dynasty, late 11th to early 12th century

-

Ghaznavid sculpted architecture, marble, Ghazni, 12–13th century AD

Seljuks (1037–1194)

[edit]The Seljuk Empire (1037–1194 AD) was a high medieval Turko-Persian Sunni Muslim empire, originating from the Qiniq branch of Oghuz Turks. At its greatest extent, the Seljuk Empire controlled a vast area stretching from western Anatolia and the Levant to the Hindu Kush in the east, and from Central Asia to the Persian Gulf in the south.

-

Mausoleum of Sultan Sanjar in Merv, Turkmenistan.

-

Seljuk-era art: Ghurid Ewer from Herat, Afghanistan, dated 1180–1210 AD. Brass worked in repousse and inlaid with silver and bitumen. British Museum.

Khwarazmians (1077–1231)

[edit]

The Khwarezmian Empire was the last Turco-Persian Empire before the Mongol invasion of Central Asia. Finely decorated Mina'i ceramics were mainly produced in Kashan, in the decades leading up to the Mongol invasion of Persia in 1219, at a time when the Khwarazmian Empire ruled the area, initially under the suzerainty of the Seljuk Empire, and independently from 1190.[187] Some of the "most iconic" productions of stonepaste vessels can be attributed to the Khwarazmian rulers, after the end of Seljuk domination (the Seljuk Empire itself ended in 1194).[188] In general, it is considered that Mina'i ware was manufactured from the late 12th century and the early 13th century, and dated Mina’i wares range from 1186 to 1224.[189]

-

Horsemen, Mina'i ware, early 13th century, Iran.[190]

-

Mina'i Bowl with horserider, early 13th century, Iran.[191]

-

Mina'i Lobed bowl, early 13th century, Iran.[192]

Mongol invasion

[edit]

The Mongols under Genghis Khan invaded Central Asia in the early 13th century. The unified Mongol Empire was succeeded by the Chagatai Khanate,[194] a Mongol and later Turkicized khanate.[195][196] that comprised the lands ruled by Chagatai Khan, second son of Genghis Khan and his descendants and successors. At its height in the late 13th century, the khanate extended from the Amu Darya south of the Aral Sea to the Altai Mountains in the border of modern-day Mongolia and China, roughly corresponding to the defunct Qara Khitai Empire.[197] Initially the rulers of the Chagatai Khanate recognized the supremacy of the Great Khan,[198] but by the reign of Kublai Khan, Ghiyas-ud-din Baraq no longer obeyed the emperor's orders.

Timurid Renaissance

[edit]During the mid-14th century, the Chagatais lost Transoxania to the Timurids circa 1370. After the Mongol invasions, a new period of prosperity thus started, the Timurid Renaissance. After conquering a city, the Timurids commonly spared the lives of the local artisans and deported them to the Timurid capital of Samarkand. After the Timurids conquered Persia in the early 15th century, many Persian artistic traits became interwoven with existing Mongol art. Timur made Samarkand one of the centers of Islamic art and remained a subject of interest to Ibn Khaldun.[199] In the mid 15th century the empire moved its capital to Herat, which became a focal point for Timurid art. As with Samarkand, Persian artisans and intellectuals soon established Herat as a center for arts and culture. Soon, many of the Timurids adopted Persian culture as their own.[200]

-

Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasawi in Hazrat-e Turkestan, Kazakhstan. Timurid architecture consisted of Persian art.

-

Akhangan's tomb, where Gawhar Shad's sister Gowhartāj is buried. The architecture is a fine example of the Timurid era in Persia.

-

Façade of Bibi Khanym Mosque, Samarkand.

Khanate of Bukhara and Khanate of Khiva

[edit]The Khanate of Bukhara was a state centered on Uzbekistan from the second quarter of the 16th century to the late 18th century. Bukhara became the capital of the short-lived Shaybanid empire during the reign of Ubaydallah Khan (1533–1540). The khanate reached its greatest extent and influence under its penultimate Shaybanid ruler, the scholarly Abdullah Khan II (r. 1557–1598). In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Khanate was ruled by the Janid dynasty (Astrakhanids or Toqay Timurids). They were the last Genghisid descendants to rule Bukhara.

-

Imamkuli-khan

-

The Registan and its three madrasahs. From left to right: Ulugh Beg Madrasah (Timurid, built 1417–1421), Tilya-Kori Madrasah (built 1646–1660) and Sher-Dor Madrasah (built 1619–1636).

-

Suzani (ceremonial hanging); late 1700s; cotton; 92 × 63; from Uzbekistan; Indianapolis Museum of Art (US)

Russian Turkestan (1867–1917)

[edit]

Central Asia fell largely under the control of Russia in the 19th century, following the Russian conquest of Central Asia. Russian Turkestan (1867–1917) was the western part of Turkestan within the Russian Empire's Central Asian territories, and was administered as a krai or governor-generalship. It comprised the oasis region to the south of the Kazakh Steppe, but not the protectorates of the Emirate of Bukhara and the Khanate of Khiva. As a consequence of Russian colonization, European fine arts – painting, sculpture and graphics – have developed in Central Asia.

-

The Emir of Bukhara and the notables of the city watch how the heads of Russian soldiers are impaled on poles. Samarkand

-

Russian troops taking Samarkand in 1868

-

They Attack Unaware

Soviet Central Asia (1918–1991)

[edit]Soviet Central Asia refers to the section of Central Asia formerly controlled by the Soviet Union, as well as the time period of Soviet administration (1918–1991). Central Asian SSRs declared independence in 1991. In terms of area, it is nearly synonymous with Russian Turkestan, the name for the region during the Russian Empire. The first years of the Soviet regime saw the appearance of modernism, which took inspiration from the Russian avant-garde movement. Until the 1980s, Central Asian arts had developed along with general tendencies of Soviet arts.

-

Urging peasants to speed up cotton production – Russian and Uzbek, Tashkent, 1920s

-

"Female Muslims- The tsar, beys and khans took your rights away" – Azeri, Baku, 1921 (Mardjani).

-

Poster of 3 different men with the word "friendship" underneath. Central Asia

-

Emblem of the Turkmen SSR.

Contemporary period

[edit]

In the 90s, arts of the region underwent some significant changes. Institutionally speaking, some fields of arts were regulated by the birth of the art market, some stayed as representatives of official views, while many were sponsored by international organizations. The years of 1990–2000 were times for the establishment of contemporary arts. In the region, many important international exhibitions are taking place, Central Asian art is represented in European and American museums, and the Central Asian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale has been organized since 2005.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Inagaki, Hajime. Galleries and Works of the MIHO MUSEUM. Miho Museum. p. 45.

- ^ Tarzi, Zémaryalaï (2009). "Les représentations portraitistes des donateurs laïcs dans l'imagerie bouddhique". KTEMA. 34 (1): 290. doi:10.3406/ktema.2009.1754.

- ^ Tamara Talbot Rice (July 2011). Visual Arts. Oxford.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica, Central Asian Arts. 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2012. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Fortenberry, Diane (2017). THE ART MUSEUM. Phaidon. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Andreeva, Petya (2022-07-14). "Re-Making Animal Bodies in the Arts of Early China and North Asia: Perspectives from the Steppe". Early China. 45: 413–465. doi:10.1017/eac.2022.7. ISSN 0362-5028. S2CID 252909244.

- ^ a b Tedesco, Laura Anne. "Mal'ta (ca. 20,000 B.C.)". The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Cohen, Claudine (2003). La femme des origines : images de la femme dans la préhistoire occidentale. Belin-Herscher. p. 113. ISBN 978-2733503362.

- ^ Karen Diane Jennett (May 2008). "Female Figurines of the Upper Paleolithic" (PDF). Texas State University. pp. 32–34. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ David Testen, "Old Persian and Avestan Phonology", Phonologies of Asia and Africa, vol. II (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, 1997), 583.

- ^ Fortenberry, Diane (2017). THE ART MUSEUM. Phaidon. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Haarmann, Harald (26 January 2021). On the Trail of the Indo-Europeans: From Neolithic Steppe Nomads to Early Civilisations. marixverlag. p. 196. ISBN 978-3-8438-0656-5.

- ^ (NOVA 2007)

- ^ (State Hermitage Museum 2007)

- ^ (Jordana 2009)

- ^ "Altaic Tribes". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher P.; Andreeva, Petya (2018). "Camp and audience scenes in late iron age rock drawings from Khawtsgait, Mongolia". Archaeological Research in Asia. 15: 4.

- ^ So, Jenny F.; Bunker, Emma C. (1995). Traders and raiders on China's northern frontier. Seattle : Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with University of Washington Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-295-97473-6.

- ^ Helfen-Maenchen,-Helfen, Otto (1973). The World of the Huns: Studies of Their History and Culture, pp.371. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 371. ISBN 9780520015968.

- ^ a b So, Jenny F.; Bunker, Emma C. (1995). Traders and raiders on China's northern frontier. Seattle : Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, in association with University of Washington Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-295-97473-6.

- ^ Prior, Daniel (2016). "Fastening the Buckle: A Strand of Xiongnu-Era Narrative in a Recent Kirghiz Epic Poem" (PDF). The Silk Road. 14: 191.

- ^ Pankova, Svetlana; Simpson, St John (21 January 2021). Masters of the Steppe: The Impact of the Scythians and Later Nomad Societies of Eurasia: Proceedings of a conference held at the British Museum, 27-29 October 2017. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-1-78969-648-6.

Inv. nr.Si. 1727- 1/69, 1/70

- ^ Francfort, Henri-Paul (1 January 2020). "Sur quelques vestiges et indices nouveaux de l'hellénisme dans les arts entre la Bactriane et le Gandhāra (130 av. J.-C.-100 apr. J.-C. environ)". Journal des Savants: 37.

- ^ Ollermann, Hans (22 August 2019). "Belt Plaque with a Bear Hunt. From Russia (Siberia). Gold. 220-180 B.C. The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia".

- ^ Chang, Claudia (2017). Rethinking Prehistoric Central Asia: Shepherds, Farmers, and Nomads. Routledge. p. 72. ISBN 9781351701587.

- ^ Jacobson, Esther (1995-01-01), "Cultural Authority in the Art of the Scythians", The Art of the Scythians, BRILL, pp. 65–80, doi:10.1163/9789004491519_007, ISBN 978-90-04-49151-9, retrieved 2024-01-03

- ^ Andreeva, Petya V. (2021-10-28). "Glittering Bodies: The Politics of Mortuary Self-Fashioning in Eurasian Nomadic Cultures (700 BCE-200 BCE)". Fashion Theory. 27 (2): 175–204. doi:10.1080/1362704x.2021.1991133. ISSN 1362-704X. S2CID 240162003.

- ^ Mallory & Mair 2000.

- ^ "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, p.73 ISBN 2-87772-337-2

- ^ Crowns similar to the Scythian ones discovered in Tillia Tepe "appear later, during the 5th and 6th century at the eastern edge of the Asia continent, in the tumulus tombs of the Kingdom of Silla, in South-East Korea. "Afganistan, les trésors retrouvés", 2006, p282, ISBN 978-2-7118-5218-5

- ^ "金冠塚古墳 – Sgkohun.world.coocan.jp". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-12-14.

- ^ Hartley, Charles W.; Yazicioğlu, G. Bike; Smith, Adam T. (2012). The Archaeology of Power and Politics in Eurasia: Regimes and Revolutions. Cambridge University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-107-01652-1.

- ^ Herzfeld, Ernst (1968). The Persian Empire: Studies in geography and ethnography of the ancient Near East. F. Steiner. p. 344.

- ^ "BACTRIA – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-08-07.

After annexation to the Persian empire by Cyrus in the sixth century, Bactria together with Margiana formed the Twelfth Satrapy.

- ^ Herodotus, 4.200–204

- ^ Strabo, 11.11.4

- ^ Herodotus 6.9

- ^ "Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom". Archived from the original on 2020-12-23. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ "Bopearachchi attributes the destruction of Ai Khanoum to the Yuezhi, rather than to the alternative 'conquerors' and destroyers of the last vestiges of Greek power in Bactria, the Sakas..." Benjamin, Craig (2007). The Yuezhi: Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria. Isd. p. 180. ISBN 9782503524290.

- ^ a b Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 373. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ^ Holt, Frank Lee (1999). Thundering Zeus : the making of Hellenistic Bactria. University of California Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9780520920095.

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 374. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ^ Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 7. ISBN 9781588392244.

- ^ "It has all the hallmarks of a Hellenistic city, with a Greek theatre, gymnasium and some Greek houses with colonnaded courtyards" (Boardman).

- ^ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 375. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ^ a b c Holt, Frank Lee (1999). Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bactria. University of California Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780520920095.

- ^ Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9780520242258.

- ^ Bernard, Paul (1967). "Deuxième campagne de fouilles d'Aï Khanoum en Bactriane". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 111 (2): 306–324. doi:10.3406/crai.1967.12124.

- ^ Source, BBC News, Another article. German story with photographs here (translation here).

- ^ Fedorov, Michael (2004). "On the origin of the Kushans with reference to numismatic and anthropological data" (PDF). Oriental Numismatic Society. 181 (Autumn): 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-06. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

- ^ KHALCHAYAN – Encyclopaedia Iranica. p. Figure 1.

- ^ "View in real colors".

- ^ Abdullaev, Kazim (2007). "Nomad Migration in Central Asia (in After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam)". Proceedings of the British Academy. 133: 87–98.

- ^ Foundation, Encyclopaedia Iranica. Greek Art in Central Asia, Afghan – Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Also a Saka according to this source

- ^ a b c d e f g Rowland, Benjamin (1971). "Graeco-Bactrian Art and Gandhāra: Khalchayan and the Gandhāra Bodhisattvas". Archives of Asian Art. 25: 29–35. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111029.

- ^ a b "The knights in chain-mail armour have analogies in the Khalchayan reliefs depicting a battle of the Yuezhi against a Saka tribe (probably the Sakaraules). Apart from the chain-mail armour worn by the heavy cavalry of the enemies of the Yuezhi, the other characteristic sign of these warriors is long side-whiskers (...) We think it is possible to identify all these grotesque personages with long side-whiskers as enemies of the Yuezhi and relate them to the Sakaraules (...) Indeed these expressive figures with side-whiskers differ greatly from the tranquil and majestic faces and poses of the Yuezhi depictions." Abdullaev, Kazim (2007). "Nomad Migration in Central Asia (in After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam)". Proceedings of the British Academy. 133: 89.

- ^ a b c d e Stokstad, Marilyn; Cothren, Michael W. (2014). Art History 5th Edition CH 10 Art Of South And Southeast Asia Before 1200. Pearson. pp. 306–308. ISBN 978-0205873470.

- ^ Puri, Baij Nath (1965). India under the Kushāṇas. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- ^ Yatsenko, Sergey A. (2012). "Yuezhi on Bactrian Embroidery from Textiles Found at Noyon uul, Mongolia" (PDF). The Silk Road. 10.

- ^ Polosmak, Natalia V. (2012). "History Embroidered in Wool". SCIENCE First Hand. 31 (N1).

- ^ Polosmak, Natalia V. (2010). "We Drank Soma, We Became Immortal…". SCIENCE First Hand. 26 (N2).

- ^ "Panel with the god Zeus/Serapis/Ohrmazd and worshiper". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Marshak, Boris; Grenet, Frantz (2006). "Une peinture kouchane sur toile". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 150 (2): 947–963. doi:10.3406/crai.2006.87101. ISSN 0065-0536.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2021). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". King of the Seven Climes: 204.

- ^ Rezakhani 2017, p. 72.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3, E. Yarshater p.209 ff

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ For the precise date: Sundermann, Werner; Hintze, Almut; Blois, François de (2009). Exegisti Monumenta: Festschrift in Honour of Nicholas Sims-Williams. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 284, note 14. ISBN 978-3-447-05937-4.

- ^ "Plate British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Sims, Vice-President Eleanor G.; Sims, Eleanor; Marshak, Boris Ilʹich; Grube, Ernst J.; I, Boris Marshak (January 2002). Peerless Images: Persian Painting and Its Sources. Yale University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-300-09038-3.

- ^ Thompson 1996, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 306.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 307-318.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 323.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 297.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 299–306.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, p. 357.

- ^ Kim 2015, p. 170.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 352–354.

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1973, pp. 354–356.

- ^ Thompson 1996, p. 47.

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284 ff

- ^ Encyclopedia Iranica

- ^ Bakker, Hans T. (12 March 2020). The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia. Barkhuis. p. 17. ISBN 978-94-93194-00-7.

- ^ Bakker, Hans T. (12 March 2020). The Alkhan: A Hunnic People in South Asia. Barkhuis. p. 10. ISBN 978-94-93194-00-7.

- ^ Cribb 2010, p. 91.

- ^ a b Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, B. A. (1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 119–120. ISBN 9789231032110.

- ^ KURBANOV, AYDOGDY (2010). THE Hephthalites: Archeological and Historical Analysis (PDF). Berlin: Berlin Freie Universität. pp. 135–136.

- ^ "DelbarjīnELBARJĪN – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ^ Ilyasov, Jangar. "The Hephthalite Terracotta // Silk Road Art and Archaeology. Vol. 7. Kamakura, 2001, 187–200": 187–197.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, B. A. (January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 183. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ^ Lerner, Judith A.; Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2011). Seals, sealings and tokens from Bactria to Gandhara : 4th to 8th century CE. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. p. 36. ISBN 978-3700168973.

- ^ Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Litvinsky, B. A. (January 1996). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. p. 177. ISBN 978-92-3-103211-0.

- ^ Dignas, Assistant Professor of History Beate; Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (2007). Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). The Fall Of The West: The Death Of The Roman Superpower. Orion. ISBN 978-0-297-85760-0.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2021). "From the Kushans to the Western Turks". King of the Seven Climes: 208.

- ^ Benjamin, Craig (16 April 2015). The Cambridge World History: Volume 4, A World with States, Empires and Networks 1200 BCE–900 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 484. ISBN 978-1-316-29830-5.

- ^ a b c Azarpay, Guitty; Belenickij, Aleksandr M.; Maršak, Boris Il'ič; Dresden, Mark J. (January 1981). Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. University of California Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6.

- ^ "Il'yasov's article references figurines wearing caftans with triangular-shaped collars on the right side. This is believed to be a style of garment that became popular in Central Asia under Hephthalite rule" in Kageyama, Etsuko (2016). "Change of suspension systems of daggers and swords in eastern Eurasia: Its relation to the Hephthalite occupation of Central Asia" (PDF). ZINBUN. 46: 200.

- ^ a b c Margottini, Claudio (20 September 2013). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) in 2001: A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-3-642-30051-6.

- ^ a b Azarpay, Guitty; Belenickij, Aleksandr M.; Maršak, Boris Il'ič; Dresden, Mark J. (January 1981). Sogdian Painting: The Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. University of California Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-520-03765-6.

- ^ a b Kurbanov, Aydogdy (2010). The Hephthalites: Archaeological and Historical Analysis (PDF) (PhD thesis). Free University, Berlin. p. 67.

- ^ Kurbanov, Aydogdy (2014). "THE HEPHTHALITES: ICONOGRAPHICAL MATERIALS" (PDF). Tyragetia. VIII: 322.

- ^ Il'yasov, Jangar Ya. (2001). "The Hephthalite Terracotta // Silk Road Art and Archaeology". Journal of the Institute of Silk Road Studies. 7. Kamakura: 187.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (15 May 2004). "Tavka (k istorii drevnix tamožennyx sooruženij Uzbekistana). Taškent-Samarkand, Izd. A. Kadyri / Institut Arxeologii A.N. Uzb, 141 p., 68 ill. + 13 pl. couleurs h.-t. (Texte bilingue ouzbek-russe, résumé en anglais). [Tavka (contribution à l'histoire des anciens édifices frontaliers de l'Ouzbékistan)]". Abstracta Iranica (in French). 25. doi:10.4000/abstractairanica.4213. ISSN 0240-8910.

- ^ Kageyama (Kobe City University of Foreign Studies, Kobe, Japan), Etsuko (2007). "The Winged Crown and the Triple-crescent Crown in the Sogdian Funerary Monuments from China: Their Relation to the Hephthalite Occupation of Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Inner Asian Art and Archaeology. 2: 12. doi:10.1484/J.JIAAA.2.302540. S2CID 130640638. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Higham, Charles (14 May 2014). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. pp. 141–142. ISBN 978-1-4381-0996-1.

- ^ a b Eastern Buddha: 549 AD - 579 AD (1 σ range, 68.2% probability) 544 AD - 595 AD (2 σ range, 95.4% probability). Western Buddha: 605 AD - 633 AD (1 σ range, 68.2%) 591 AD - 644 AD (2 σ range, 95.4% probability). in Blänsdorf, Catharina (2015). "Dating of the Buddha Statues – AMS 14C Dating of Organic Materials".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The radiate crown is comparable to the crown of the king on the "Yabghu of the Hephthalites" seal. See: Lerner, Judith A.; Sims-Williams, Nicholas (2011). Seals, sealings and tokens from Bactria to Gandhara : 4th to 8th century CE. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-3700168973.

- ^ KURBANOV, AYDOGDY (2010). THE HEPHTHALITES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS (PDF). Berlin: Berlin Freie Universität. p. 69, item 1).

- ^ Latest 5th-6th century CE date in Livshits (2000) LIVSHITS, V. A. (2000). "Sogdian Sānak, a Manichaean Bishop of the 5th–Early 6th Centuries" (PDF). Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 14: 48. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049013.. According to earlier sources (Bivar (1969) and Livshits (1969), repeated by the British Museum the seal was dated to the 300-350 CE: in Naymark, Aleksandr. "SOGDIANA, ITS CHRISTIANS AND BYZANTIUM: A STUDY OF ARTISTIC AND CULTURAL CONNECTIONS IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY MIDDLE AGES" (PDF): 167. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-02-27. Retrieved 2021-02-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), "Stamp-seal; bezel British Museum". The British Museum. - ^ Blänsdorf, Catharina (2015). "Dating of the Buddha Statues – AMS 14C Dating of Organic Materials".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Petzet, Michael, ed. (2009). The Giant Buddhas of Bamiyan. Safeguarding the remains (PDF). ICOMOS. pp. 18–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-02-04. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (5 December 2006). "Afghans consider rebuilding Bamiyan Buddhas". International Herald Tribune/The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2014.

- ^ Morgan, Kenneth W (1956). The Path of the Buddha. Motilal Banarsidass publishers. p. 43. ISBN 978-8120800304. Retrieved 2 June 2009 – via Google Books.

- ^ "booklet web E.indd" (PDF). Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (6 December 2006). "From Ruins of Afghan Buddhas, a History Grows". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ a b c Higuchi, Takayasu; Barnes, Gina (1995). "Bamiyan: Buddhist Cave Temples in Afghanistan". World Archaeology. 27 (2): 299. doi:10.1080/00438243.1995.9980308. ISSN 0043-8243. JSTOR 125086.

- ^ Alram, Michael; Filigenzi, Anna; Kinberger, Michaela; Nell, Daniel; Pfisterer, Matthias; Vondrovec, Klaus. "The Countenance of the other (The Coins of the Huns and Western Turks in Central Asia and India) 2012-2013 exhibit: 14. KABULISTAN AND BACTRIA AT THE TIME OF "KHORASAN TEGIN SHAH"". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ "The globelike crown of the princely donor has parallels in Sasanian coin portraits. Both this donor and the Buddha at the left are adorned with hair ribbons or kusti, again borrowed the Sasanian royal regalia" in Rowland, Benjamin (1975). The art of Central Asia. New York, Crown. p. 88.

- ^ "Lost, Stolen, and Damaged Images: The Buddhist Caves of Bamiyan". huntingtonarchive.org.

- ^ Walter (1998), pp. 5–9.

- ^ Hansen (2012), p. 66.

- ^ Walter (1998), pp. 21–17.

- ^ 阮, 荣春 (May 2015). 佛教艺术经典第三卷佛教建筑的演进 (in Chinese). Beijing Book Co. Inc. p. 184. ISBN 978-7-5314-6376-4.

- ^ (Other than Kizil)... "The nearby site of Kumtura contains over a hundred caves, forty of which contain painted murals or inscriptions. Other cave sites near Kucha include Subashi, Kizilgaha, and Simsim." in Buswell, Robert E.; Lopez, Donald S. (24 November 2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 438. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- ^ Vignato, Giuseppe (2006). "Archaeological Survey of Kizil: Its Groups of Caves, Districts, Chronology and Buddhist Schools". East and West. 56 (4): 359–416. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757697.

- ^ References BDce-888、889, MIK III 8875, now in the Hermitage Museum."俄立艾爾米塔什博物館藏克孜爾石窟壁畫". www.sohu.com (in Chinese).

- ^ Rhie, Marylin Martin (15 July 2019). Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia, Volume 2 The Eastern Chin and Sixteen Kingdoms Period in China and Tumshuk, Kucha and Karashahr in Central Asia (2 vols). BRILL. pp. 651 ff. ISBN 978-90-04-39186-4.

- ^ Waugh, Daniel (Historian, University of Washington). "Kizil". depts.washington.edu. Washington University. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan

- ^ A. M. Belenitskii and B. I. Marshak (1981), "Part One: the Paintings of Sogdiana" in Guitty Azarpay, Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, p. 47, ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- ^ A. M. Belenitskii and B. I. Marshak (1981), "Part One: the Paintings of Sogdiana" in Guitty Azarpay, Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, p. 13, ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- ^ A. M. Belenitskii and B. I. Marshak (1981), "Part One: the Paintings of Sogdiana" in Guitty Azarpay, Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, pp 34–35, ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ Compareti (University of California, Berkeley), Matteo (2007). "The Chinese Scene at Afrāsyāb". Eurasiatica.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (2004). The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. British Library. Serindia Publications, Inc. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-932476-13-2.

- ^ Grenet, Frantz (2004). "Maracanda/Samarkand, une métropole pré-mongole". Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales. 5/6: Fig. D.

- ^ Compareti (University of California, Berkeley), Matteo (2015). "Ancient Iranian Decorative Textiles". The Silk Road. 13: 38.

- ^ "Hermitage Museum".

- ^ Gorelik, Michael (1979). "Oriental Armour of the Near and Middle East from the Eighth to the Fifteenth Centuries as Shown in Works of Art", by Michael Gorelik, in: Islamic Arms and Armour, ed. Robert Elgood, London 1979. Robert Elgood.

- ^ Sims, Eleanor (2002). Peerless images : Persian painting and its sources. New Haven : Yale University Press. pp. 293–294. ISBN 978-0-300-09038-3.

- ^ Carter, M.L. "Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org.

A gilt silver plate depicting a princely boar hunt, excavated from a tomb near Datong dated to 504 CE, is close to early Sasanian royal hunting plates in style and technical aspects, but diverges enough to suggest a Bactrian origin dating from the era of the Kushano-Sasanian rule (ca. 275–350 CE)

- ^ HARPER, PRUDENCE O. (1990). "An Iranian Silver Vessel from the Tomb of Feng Hetu". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 4: 51–59. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24048350.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2023-03-26. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Wu, Mandy Jui-man (2004). "Exotic Goods as Mortuary Display in Sui Dynasty Tombs—A Case Study of Li Jingxun's Tomb". Sino-Platonic Papers. 142.

- ^ a b CARPINO, ALEXANDRA; JAMES, JEAN M. (1989). "Commentary on the Li Xian Silver Ewer". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 3: 71–75. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24048167.

- ^ a b Whitfield, Susan (13 March 2018). Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road. Univ of California Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-520-95766-4.

- ^ Watt, James C. Y. (2004). China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

- ^ Otani, Ikue (January 2015). "Inlaid Rings and East-West Interaction in the Han-Tang Era". 中国北方及蒙古、貝加爾、西伯利亜地区古代文化. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ Lingley, Kate A. (2014). "SILK ROAD DRESS IN A CHINESE TOMB: XU XIANXIU AND SIXTH-CENTURY COSMOPOLITANISM" (PDF). The Silk Road. 12: 2.

- ^ Худяков, Юлий (15 May 2022). Археология степной евразии. Искусство кочевников южной сибири и центральной азии. Учебное пособие для вузов (in Russian). Litres. p. 50. ISBN 978-5-04-141329-3.

- ^ ALTINKILIÇ, Dr. Arzu Emel (2020). "Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi" (PDF). Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research: 1101–1110. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

- ^ Narantsatsral, D. "THE SILK ROAD CULTURE AND ANCIENT TURKISH WALL PAINTED TOMB" (PDF). The Journal of International Civilization Studies.

- ^ Cosmo, Nicola Di; Maas, Michael (26 April 2018). Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity: Rome, China, Iran, and the Steppe, ca. 250–750. Cambridge University Press. pp. 350–354. ISBN 978-1-108-54810-6.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 185–186. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Göbl 1967, 254; Vondrovec tyre 254

- ^ Alram, Michael; Filigenzi, Anna; Kinberger, Michaela; Nell, Daniel; Pfisterer, Matthias; Vondrovec, Klaus. "The Countenance of the other". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ Alram, Michael; Filigenzi, Anna; Kinberger, Michaela; Nell, Daniel; Pfisterer, Matthias; Vondrovec, Klaus. "The Countenance of the other (The Coins of the Huns and Western Turks in Central Asia and India) 2012-2013 exhibit: 13. THE TURK SHAHIS IN KABULISTAN". Pro.geo.univie.ac.at. Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Archived from the original on October 27, 2020. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Allegranzi, Viola; Aube, Sandra (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 181. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Vacca, Alison (2017). Non-Muslim Provinces under Early Islam: Islamic Rule and Iranian Legitimacy in Armenia and Caucasian Albania. Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1107188518.

- ^ Rante, Rocco (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 178. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Blair, Sheila S. (2009). "Būyid art and architecture". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- ^ "Ewer". Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art.

- ^ "Rosewater bottle". Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art.

- ^ Karev, Yuri (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 222. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Karev, Yury (2013). Turko-Mongol rulers, cities and city life. Leiden: Brill. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9789004257009.

The ceramics and monetary finds in the pavilion can be dated to no earlier than to the second half of the twelfth century, and more plausibly towards the end of that century. This is the only pavilion of those excavated that was decorated with paintings, which leave no doubt about the master of the place. (...) The whole artistic project was aimed at exalting the royal figure and the magnificence of his court. (...) the main scenes from the northern wall represents the ruler sitting cross-legged on a throne (see Figs 13, 14) (...) It was undoubtedly a private residence of the Qarakhanid ruler and his family and not a place for solemn receptions.

- ^ a b Frantz, Grenet (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. pp. 221–222. ISBN 978-8412527858.

Peintures murales qui ornaient (...) la résidence privée des derniers souverains qarakhanides de Samarkande (fin du 12ième - début du 13ième siècle (...) le souverain assis, les jambes repliées sur le trône, tient une flèche, symbole du pouvoir (Fig.171).

- ^ Karev, Yury (2013). Turko-Mongol rulers, cities and city life. Leiden: Brill. p. 120. ISBN 9789004257009.

We cannot exclude the possibility that this action was related to the dramatic events of the year 1212, when Samarqand was taken by the Khwarazmshah Muḥammad b. Tekish.

- ^ Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovell-Hoare (2016), Uzbekistan, 2nd edition, Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, pp 12–13, ISBN 978-1-78477-017-4.

- ^ Sophie Ibbotson and Max Lovell-Hoare (2016), Uzbekistan, 2nd edition, Bradt Travel Guides Ltd, pp 14–15, ISBN 978-1-78477-017-4.

- ^ Karev, Yury (2013). Turko-Mongol rulers, cities and city life. Leiden: Brill. pp. 115–120. ISBN 9789004257009.

The ceramics and monetary finds in the pavilion can be dated to no earlier than to the second half of the twelfth century, and more plausibly towards the end of that century. This is the only pavilion of those excavated that was decorated with paintings, which leave no doubt about the master of the place. (...) The whole artistic project was aimed at exalting the royal figure and the magnificence of his court. (...) It was undoubtedly a private residence of the Qarakhanid ruler and his family and not a place for solemn receptions.

- ^ Collinet, Anabelle (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 234. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Collinet, Anabelle (2022). Splendeurs des oasis d'Ouzbékistan. Paris: Louvre Editions. p. 231. ISBN 978-8412527858.

- ^ Arjomand 2012, p. 410-411.

- ^ a b Levi & Sela 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Bosworth 1963, p. 4.

- ^ Bosworth 2006.

- ^ Schlumberger, Daniel (1952). "Le Palais ghaznévide de Lashkari Bazar". Syria. 29 (3/4): 263 & 267. doi:10.3406/syria.1952.4789. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4390312.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org.

- ^ HEIDEMANN, STEFAN; DE LAPÉROUSE, JEAN-FRANÇOIS; PARRY, VICKI (2014). "The Large Audience: Life-Sized Stucco Figures of Royal Princes from the Seljuq Period". Muqarnas. 31: 35–71. doi:10.1163/22118993-00311P03. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 44657297.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Komaroff, 4; Michelsen and Olafsdotter, 76; Fitzwilliam Museum: "Mina’i, meaning ‘enamelled’ ware, is one of the glories of Islamic ceramics, and was a speciality of the renowned ceramics centre of Kashan in Iran during the decades of the late 12th and early 13th centuries preceding the Mongol invasions".

- ^ "While stonepaste vessels are often attributed to the Seljuq period, some of the most iconic productions in the medium took place after this dynasty lost control over its eastern territories to other Central Asian Turkic groups, such as the Khwarezm-Shahis" in Rugiadi, Martina. "Ceramic Technology in the Seljuq Period: Stonepaste in Syria and Iran in the Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art (2021). Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts: Mina'i ware. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 9780195189483.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Carboni, Stefano (1994). Illustrated Poetry and Epic Images. Persian paintings of the 1330s and 1340s (PDF). New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Frederik Coene (2009). The Caucasus – An Introduction. Routledge. p. 114. ISBN 978-1135203023.

- ^ Black, Cyril E.; Dupree, Louis; Endicott-West, Elizabeth; Matuszewski, Daniel C.; Naby, Eden; Waldron, Arthur N. (1991). The Modernization of Inner Asia. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-315-48899-8. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ Upshur, Jiu-Hwa L.; Terry, Janice J.; Holoka, Jim; Cassar, George H.; Goff, Richard D. (2011). Cengage Advantage Books: World History (5th ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 433. ISBN 978-1-133-38707-7. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- ^ See Barnes, Parekh and Hudson, p. 87; Barraclough, p. 127; Historical Maps on File, p. 2.27; and LACMA for differing versions of the boundaries of the khanate.

- ^ Dai Matsui – A Mongolian Decree from the Chaghataid Khanate Discovered at Dunhuang. Aspects of Research into Central Asian Buddhism, 2008, pp. 159–178

- ^ Marozzi, Justin (2004). Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, conqueror of the world. HarperCollins.

- ^ B.F. Manz; W.M. Thackston; D.J. Roxburgh; L. Golombek; L. Komaroff; R.E. Darley-Doran (2007). "Timurids". Encyclopedia of Islam, online edition. "During the Timurid period, three languages, Persian, Turkish, and Arabic were in use. The major language of the period was Persian, the native language of the Tajik (Persian) component of society and the language of learning acquired by all literate and/or urban Turks. Persian served as the language of administration, history, belles lettres, and poetry."

Sources

[edit]- Arjomand, Said Amir (2012). "Patrimonial state". In Böwering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Mirza, Mahan (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15034-5.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1963). The Ghaznavids:994–1040. Edinburgh University Press.

- Bosworth, C.E. (1968). "The Development of Persian Culture under the Early Ghaznavids". Iran. 6. Taylor & Francis, Ltd.: 33–44. doi:10.2307/4299599. JSTOR 4299599.