Arnsberg Castle

Arnsberg Castle (German: Schloss Arnsberg) is a former palace in Arnsberg, North Rhine-Westphalia in Germany. It is a located on a 256 m (840 ft) high hill.[1]

Arnsberg castle was constructed as the seat of the counts of Werl-Arnsberg, probably around 1100. It served as residence of the counts of Arnsberg until 1368.[2] With the transition of the county into the possession of the Electorate of Cologne, it became the centre of power of the Duchy of Westphalia.[2] The electors resided, hunted and feasted there during their visits, the Landdrost had his seat there as governor, and partially the provincial assemblies also took place there.[2]

Elector Salentin of Isenburg (1532–1610) had the castle redesigned in the renaissance style around 1575.[2] Under Maximilian Henry of Bavaria (1621–1688), there was another renovation in 1654.[2] A fundamental redesign in the baroque style took place from 1739 onwards under Elector Clemens August of Bavaria (1700–1761) with help of the architect Johann Conrad Schlaun (1695–1773), creating a cheerful palace and hunting lodge.[2] Arnsberg castle was destroyed in 1762 during the Seven Years' War.[2]

Today, the complex is a castle ruin and can be freely visited.[2]

History

[edit]

The development and construction history of the complex can be traced more precisely through artistic representations, plans, and descriptions only since the 16th century. Only a larger-scale archaeological investigation could provide insights into earlier phases of construction. Excavations in 2023 revealed medieval wall structures, which may have belonged to an early ring wall.[3]

Medieval castle: the "Grafenburg"

[edit]

The early history of the complex is largely obscure. Around 1060, count Bernhard II of Werl (1010–1070) built the so-called old castle, also known as "Rüdenburg", on a hill at the confluence of the Walpke and Ruhr rivers. Between 1070 and 1080, Konrad II (1040–1092) relocated the seat of the Counts of Werl to Arnsberg. Earlier, the construction of the "Grafenburg" (i.e., the location of the current castle ruins) on the hill opposite "Rüdenburg" was attributed to him, with the year of origin given as 1077.[1] Today, the relocation of the Count's seat from Werl to Arnsberg is attributed to Count Friedrich the Belligerent (1075–1124) around 1100.

In 1102, a castle in the area of present-day Arnsberg was destroyed by Frederick I, Archbishop of Cologne (1075–1131), because count Friedrich had sided with Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV (1050–1106) during the Investiture Controversy.[1] According to Leidinger, this was the "Rüdenburg", not, as stated in older literature, the "Grafenburg".

Another destruction of the castle occurred in 1166 under the rule of count Heinrich I, whose brother's murder triggered a punitive campaign by Henry the Lion (1129/31-1195).[1] A third destruction occurred in 1366 during a feud between count Gottfried IV of Arnsberg (1295–1371) and count Engelbert III of the Mark (1330–1391).[1] In both cases, the castle was rebuilt.[1]

Little is known about the appearance of the medieval castle.[1] It is likely that even then, a main building with strong corner towers enclosed the castle area to the south. The first indications of a castle chapel date back to 1114. The castle was the nucleus of the town of Arnsberg, which emerged from a small settlement of vassals and craftsmen. The castle itself was the residential and administrative centre of the County of Arnsberg. In two documents from 1259 and 1270, an "aurea caminata" (a golden hall) is mentioned, indicating a partly representative furnishing. The construction of a three-aisled chapel and the layout of the main tower also hint at a magnificent complex.

16th century: Salentin of Isenburg and the creation of a renaissance castle

[edit]After the sale of the County of Arnsberg to the Electorate of Cologne in 1368, as count Gottfried IV was childless and last of his line, the castle served as the residence of the Archbishops of Cologne when they visited the Duchy of Westphalia.[1][2] During the Soest Feud (1444–1449), it served as the main base for the troops of Archbishop Dietrich II von Moers (1385–1463). During the following period, the castle was little used and fell into disrepair.

Initially, there were no changes to the structural condition. This changed only when a redesign was carried out under Elector Salentin of Isenburg (1532–1610) in 1575.[1] The defensive character, which was never completely lost in subsequent constructions, was preserved. The redesign focused on dismantling the roof and timberwork of the castle and reusing and integrating the walls for cost reasons. The plans for the renovation were provided by the architect Laurenz von Brachum. Probably, his son, who also appears in sources as Johannes von Arnsberg, was the actual builder. The architects of the Duke of Jülich and the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, Hans Wezel, were also consulted for advice. The construction was not completed by the time of Salentin's abdication.[1] Construction continued under his successors, Gebhard Truchsess von Waldburg (1547–1601), Ernest of Bavaria (1554–1612), and Ferdinand of Bavaria (1577–1650).[1]

16th century: A description of how the castle looked like

[edit]

A map created around 1653 provides at least a basic representation of the medieval castle. Approaching from the town, a passage allowed access to the castle area. Further up the hill, there was a gatehouse located between outworks and battery fortifications. Passing by additional outworks, visitors entered a gate in the western tower and reached the courtyard of the castle complex. This courtyard was almost entirely surrounded by buildings except for an area in the east. In the west was the seat of the Landdrost, the representative of the sovereign in the Duchy of Westphalia. In the middle of the courtyard, measuring 130 m × 60 m (430 ft × 200 ft), was the castle chapel, connected to the Landdrost wing by a corridor. Directly connected to the chapel was the keep, also known as the White Tower, which towered over the entire complex. The tower and chapel were still surrounded by a wall, with an additional building of unknown purpose attached to it.

In the northern part were likely economic buildings, including the Gallows Gate, another small gate to the north. This area also included additional structures such as a brewhouse, a battery facing north, and the powder tower. In the east were likely stables with a carriage house, and further south, a slaughterhouse and well house. The well was constructed in 1576 during Salentin's time, reaching a depth of 43 meters into the rock of the Schlossberg.

A short east wing adjoined the main building, situated between the aforementioned west and east towers, both four stories high. In front of the east tower was another fortification with another building, perhaps serving as a guardhouse. The main building underwent a significant architectural redesign, featuring a large hall (38 m × 19 m (125 ft × 62 ft)) on the first floor, unusually supported by iron at that time. The castle chapel, in particular, was splendidly furnished. A contemporary inventory by the Oberkellner Hermann Dücker listed forty-nine rooms in total, including a castle library and a chamber for Jesuits.

17th century: Maximilian Henry of Bavaria

[edit]

In the following decades, not least the Thirty Years' War contributed to the deterioration of the complex, until under Elector Maximilian Henry of Bavaria (1621–1688) from 1654, first a restoration and later a redesign took place.[1] Immediately after taking office, he ordered the responsible monasteries of Wedinghausen and Rumbeck to restore the dilapidated waterworks. It is not entirely clear when the waterworks were originally built. It is unlikely to date back to Salentin's time, as he had the well deepened.

Improvements to the defensive structures began early on. The three artillery batteries in front of the east and west towers and to the north were expanded with partly underground outworks.

The actual renovation work was led by the Waldeck master builder Hans Deger. He submitted initial designs in early 1661. After modifications requested by the Elector, construction began with the west tower. This was followed by the central building. About a year later, the construction work was completed.

The two corner towers were expanded. In the western tower, the upper floors each had six rooms, including the Elector's main room. Instead of wooden flooring, this room featured a floor made of delicate ashlar stones. Windows and doors were also enlarged. Similarly, the other tower was redesigned. In the main building, four rooms were separated from the great hall, serving as antechambers, audience rooms, and dressing rooms. The floor was paved with stones. Above the hall, a gallery was built with eight habitable rooms, each with a fireplace and stove. Beneath the floor with the hall were five cross vaults housing the kitchen, dispensary, wine cellar, bakery, silver chamber, and similar spaces.

The external appearance of the Salentin building hardly changed. Particularly, the buildings north of the main building underwent little change. A distinction was now made between new and old buildings. In total, there were now 68 rooms. The Elector's quarters were particularly lavish, adorned with gilded leather tapestries and silk coverings. The audience room was furnished for the Elector's confidant Franz Egon von Fürstenberg-Heiligenberg (1626–1682). To pursue his alchemical interests, the Elector also had a laboratory and a pharmacy installed.

Even after completion, there were ongoing problems. The first renovation works became necessary as early as 1670. Lightning struck the White Tower, dating back to the Middle Ages, three times between 1660 and 1683, causing significant damage.[1] In 1685/86, the tower was renovated, and adjacent buildings in disrepair were demolished, leading to design proposals for the expanded castle square. The upper floor of the adjacent castle chapel proved irreparable. The resulting drawings show the only known floor plan of the tower and chapel. The chapel had a flattened apse and was supported by four pillars. Originally, the chapel had two floors. One chapel was intended for servants and the other for the castle lords. The upper floor was secularized in the 16th century.

18th century: Joseph Clemens of Bavaria

[edit]

In the last years of Maximilian Heinrich's rule, further work was necessary to halt the decay of the castle. Similarly, under Joseph Clemens of Bavaria (1671–1723), the situation persisted. The White Tower continued to be a concern. In 1700, a tower of the main building was damaged by fire. Again, in 1711, a fire broke out in the castle.[1] The curtain wall and various outbuildings proved increasingly dilapidated. After some emergency measures, a thorough examination of the building was conducted in 1717, involving the master builder Lambert Friedrich Corfey. This revealed massive damage. However, a comprehensive and costly renovation did not take place. The poor condition of the building was brought to attention by the Oberkellner of the Duchy of Westphalia, Bernhard Adolf von Dücker, in 1718. He pointed out that the winter weather had worsened the situation. Ceilings had collapsed due to rainwater leakage, and beams had rotted. He feared that the next provincial assembly could not be held in the castle. Around 1720, the Landdrost Ferdinand Caspar von Droste and the Oberkellner Bernd Adolf von Dücker made proposals, outlining the further development with the demolition of dilapidated buildings and the construction of a baroque three-wing complex. Another fire occurred in 1723, destroying the grand hall.[1]

18th century: Clemens August of Bavaria: creation of a baroque residential palace and hunting lodge

[edit]

Clemens August of Bavaria (1700–1761), the successor, found a building that resembled a ruin in parts.[1] Consequently, Clemens August decided on a restoration, accompanied by significant redesign into a residential castle and hunting lodge.[1] A considerable portion of the costs was borne by the Estates. Initial funds were allocated under Joseph Clemens. In 1723, another approval of 10,000 talers was granted solely for the castle construction.

This construction began around 1729/30 under the prominent baroque architect Johann Conrad Schlaun (1695–1773).[1] The works were likely completed by 1743 with the consecration of the castle chapel. Most of the side and ancillary buildings were demolished, including the old chapel, the keep, and the Landdrost wing.[1] This created a large area north of the main building, enclosed by a simple wall. Only in the northwest did some outbuildings remain.[1]

The main building with the two corner towers likely remained largely intact. The main building was about 36.30 m (119.1 ft) wide and 21.5 m (71 ft) deep.[1] The ground floor consisted of a barrel vault with a height of 5.50 m (18.0 ft), followed by an intermediate floor with a cross vault at the same height.[1] The grand hall above was approximately 7.50 m (24.6 ft) high.[1] With various intermediate ceilings, the height reached 20 m (66 ft) without the roof.[1]

The 16 m × 16 m (52 ft × 52 ft) towers were crowned with semi-circular domes and a lantern, making the actual towers 27 m (89 ft) high. With the roof and lantern, they stood about 50 m (160 ft) tall. The towers were similar to the towers of Bensberg Castle near Cologne, and the Princely Abbey of Corvey.[1]

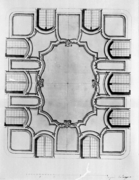

Two side wings were added to the main building in the north direction. These were about 30 m (98 ft) long and 14 m (46 ft) wide, with three floors above a basement in the courtyard area. The castle chapel was located in the eastern wing. In total, the habitable area of the castle, excluding basement and attic, was 3,500 m2 (38,000 sq ft).[1] Thus, a representative, symmetrical, three-winged Baroque palace complex was created.[1] The entrance was from the courtyard side via a magnificent staircase. Design drawings by Schlaun have survived.[1]

The centrepiece of the castle remained the grand hall with two large fireplaces. This hall provided ample space for a procession to listen to a sermon. Venetian tapestries adorned the walls, and six large paintings depicting hunting scenes and fourteen portrait paintings hung in the hall. These included portraits of the last five Cologne electors, members of the Wittelsbach family, and Emperor Louis IV the Bavarian (1282–1347). The hall was illuminated by eleven large chandeliers and twenty-four wall sconces. It contained twelve dining tables, a musicians' table, and sixty chairs. The billiard room included not only the billiard table but also several gaming tables. The Elector's bedroom had yellow silk damask wallpaper and a canopy bed made of similar fabric. There were tables with inlays, chests of drawers, a gaming table, and precious mirrors. Additionally, there was a writing cabinet and a bedroom. A painting of Charlemagne adorned the dining room. Other rooms included an audience room and a dressing room, where the Westphalian Estates Cup was kept. The chapel, housed in a side wing, had four benches, an altar with a Madonna, and additional religious images. Additionally, there were rooms in the side wings for the entourage, servants, various officials, as well as kitchen and utility rooms.

During the Seven Years' War, the castle and the city were bombarded and set on fire and destroyed in April 1762 by Prussian and Hanoverian troops under the command of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick (1735–1806), to force a French garrison allied with Electoral Cologne, consisting of 200 men, to surrender.[1][4] During the bombardment, 2,000 canon shots, 300 fireballs, and 1,200 canon balls were fired on the castle.[1] What bombs and grenades left standing was rendered unusable by mines days later.[1] It was strategic unimportant decision and led to a loss of cultural important residential castle and hunting lodge.[2]

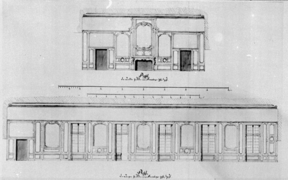

Gallery: Designs by Johan Conrad Schlaun for Schloss Arnsberg (1730-1735)

[edit]The LWL Landesmuseum in Münster has a set of designs made by Johan Conrad Schlaun for Schloss Arnsberg.

-

The outside staircase

-

The fire place and side walls in the great hall

-

Castle chapel plasterwork ceiling (?)

-

Castle chapel plasterwork ceiling

-

Castle chapel altar

Castle ruins

[edit]

The castle complex itself has since become a ruin.

Among others, the Düsseldorf garden architect Maximilian Friedrich Weyhe transformed the Schlossberg area into a landscape park in the romantic style from 1818 to 1821. Somewhat later, some of the original gothic arches of the ruin were reconstructed.

In 1897, the city of Arnsberg acquired the castle ruins.[1] The plans of the architect Engelbert Seibertz to build a Kaiser Wilhelm Tower with a restaurant and museum were thwarted by the outbreak of the First World War.[1] Recently, there has been another comprehensive redesign of the area. The overgrown walls were cleared, a large-scale memorial for war victims was relocated to another location, and a circular path was created. In addition, below the ruin, a vineyard inspired by historical models was established.

It is said that the pastor and poet August Disselhoff (1829-1903) composed the song "Nun ade, du mein lieb Heimatland" (Now farewell, my beloved homeland) in the ruins of the Arnsberg Castle. For several years now, a ruins festival has been held regularly to ensure the preservation of the ruin and to enhance the attractiveness of the site.

See also

[edit]Other palaces, residences and hunting lodges of Clemens August of Bavaria;

- Schloss Ahaus

- Augustusburg and Falkenlust Palaces, Brühl

- Clemenswerth Palace

- Electoral Palace, Bonn

- Schloss Herzogsfreude

- Schloss Hirschberg near Arnsberg

- Schloss Liebenburg

- Mergentheim Palace

- Schloss Neuhaus in Paderborn

- Osnabrück Palace

- Poppelsdorf Palace in Bonn

- Schloss Sassenberg

- Vinea Domini in Bonn

- Amtshaus Wiedenbrück (also known as Burg Reckenberg)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Strothmann, Karl-Heinz (1969). "Geschichte der Grafenburg, des späteren kurkölnischen Jagdschlosses zu Arnsberg". Burgen und Schlösser – Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). 10: 45–49.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fischer, Ferdy; Anneser, Toni (1992). Castles looking down from the hills Stately Homes dreaming in the valleys. Münster: Aschendorf Verlag. pp. 41–48, 104–107. ISBN 3-402-06046-9.

- ^ Claßen, Eric (30 August 2023). "Archäologische Grabungen auf dem Arnsberger Schlossberg". Westfalenpost (in German). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ Rosenkranz, Georg Joseph (1849). "Belagerung und Zerstörung des Schlosses Arnsberg 1762". Westfälische Zeitschrift für vaterländische Geschichte und Altertumskunde (in German). 11: 334–339.

Literature

[edit]- Rosenkranz, Georg Joseph (1849). "Belagerung und Zerstörung des Schlosses Arnsberg 1762". Westfälische Zeitschrift für vaterländische Geschichte und Altertumskunde (in German). 11: 334–339.

- Mommertz, Bernhard (1917). Das Schloß zu Arnsberg : kurzgefaßte Schilderung seiner Schicksale durch 7 Jahrhunderte (in German). Arnsberg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Strothmann, Karl-Heinz (1967). Das Jagd- und Lustschloss des Kurfürsten Clemens August Arnsberg (in German). Arnsberg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Strothmann, Karl-Heinz (1969). "Geschichte der Grafenburg, des späteren kurkölnischen Jagdschlosses zu Arnsberg". Burgen und Schlösser – Zeitschrift für Burgenforschung und Denkmalpflege (in German). 10: 45–49.

- Sandgathe, Günter (1986). "Jagd und Politik am Hoflager des Kurfürsten Clemens August im Herzogtum Westfalen (1724-1761)" (PDF). Westfälische Zeitschrift (in German). 136: 335–389.

- Haltaufderheide, Uwe (1990). Die Baudenkmäler der Stadt Arnsberg (in German). Arnsberg. pp. 33–37. ISBN 3-928394-01-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fischer, Ferdy; Anneser, Toni (1992). Castles looking down from the hills Stately Homes dreaming in the valleys. Münster: Aschendorf Verlag. pp. 41–48, 104–107. ISBN 3-402-06046-9.

- Rauschkolb, Mark (2002). "Die kurfürstliche Residenz Arnsberg als Festung – Archäologische Untersuchungen zur frühneuzeitlichen Befestigung des Schlossberges". Westfalen: Hefte für Geschichte, Kunst und Volkskunde (in German). 78: 221–236.

- Friedhoff, Jens (2002). Theiss-Burgenführer Sauerland und Siegerland. 70 Burgen und Schlösser (in German). Stuttgart: Theiss Verlag. ISBN 978-3806217063.

- Conrad, Horst (2013). "Anmerkungen zur Baugeschichte des Schlosses Arnsberg". Südwestfalenarchiv (in German). 13: 69–94.

External links

[edit]- "Association for reviving the Arnsberg Castle ruines". schlossbergarnsberg.com/ (in German). Retrieved 5 May 2024.