Arn Gill (North Yorkshire)

| Arn Gill | |

|---|---|

Arn Gill: ravine with former lead mine | |

| Etymology | Arn = "eagle".[1] Gill = river-cut ravine (northern England).[2] |

| Location | |

| Country | England |

| County | North Yorkshire |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Arn Gill Head, Swaledale |

| • coordinates | 54°23′19.8″N 02°07′57.7″W / 54.388833°N 2.132694°W |

| Mouth | |

• location | River Swale |

• coordinates | 54°23′18.8″N 02°08′34.2″W / 54.388556°N 2.142833°W |

| Basin features | |

| Landmarks | Former lead mine and spoil heap |

| Waterfalls | There are waterfalls near the outfall to the River Swale. |

| Tributary of River Swale | |

Arn Gill is a ravine or gully containing a beck of the same name, near the village of Muker in Swaledale, North Yorkshire, England. The ravine and beck run steeply downhill from the stream's source in Arn Gill Head, and the beck disgorges into the River Swale below.

The ravine contains remnants of the former Adelaide Level lead mine, which is named after Lady Adelaide Lamont, a descendant of Judge Jeffreys. In 1865 a strike was made there, which yielded about £12,000 (equivalent to £1,449,217 in 2023) worth of galena or lead ore. The mine closed in 1920. Miners worked in bad conditions in North Yorkshire lead mines during the Adelaide Level's era, with over 62% of local mines having extremely impure air. The most common occupational disease for miners was silicosis.

Description

[edit]Arn Gill is located in Swaledale, North Yorkshire, England, north of Muker and on the east side of the River Swale. It is a river-cut ravine or gully, containing a beck, also known as Arn Gill. The beck runs east–west in its gully, falling steeply downhill from its source on the fell Arn Gill Head, to its discharge point as a tributary of the River Swale.[3]

Former lead mining

[edit]

Lead mines in the Arn Gill area were worked between 1751 and 1921.[4] However the Adelaide Level lead mine at Arn Gill near Muker was comparatively short-lived. This is the mine of which the remains are still visible.[5]

George Cottingham's strike

[edit]Between Keldside and Kisdon are galena ore veins, and the south-eastern ends of these veins run below Arn Gill. Early attempts at mining this source were in 1811 and 1866 at West Arn Gill, which is to the north of Arn Gill, but "no ore was found". There had been drainage works in Arn Gill in the early nineteenth century, for other mines further up the hill. But when the deeper Adelaide Level was driven there, in 1865, a rich vein of ore was found by Sir George Denys' A.D. Company. Muker lead miner George Cottingham (c.1814–1876) and his son George (born c.1850) "hit a rich flat of ore" and according to historians Mike Gill and Edward Fawcett they were said to have thereby brought the company about £12,000 (equivalent to £1,449,217 in 2023).[5][6] Thirty more tons of ore were found in Adelaide Level in 1918. However, by 1920 it was costing too much to pump out water, and the mine was abandoned.[5][7][8] The Adelaide Level was named after Lady Adelaide Lamont of Knockdow, daughter of Sir George Denys,[9][10] and descendant of Judge Jeffreys.[11]

Working conditions

[edit]

A gill (or ravine) like Arn Gill could facilitate lead mining where the ravine was already cut into the ore vein. That meant that a horizontal tunnel, or adit level, could be dug into the side of the ravine where ore was found. Some of these levels were named horse levels, because they were big enough for a small horse and cart.[12][13]

In 1864 a commissioned report on the condition of the lead miners of Yorkshire was issued.[14]

The deep valleys ramifying through the hills offer frequent opportunities for driving adit levels at various elevations, by which mode of access all subsequent operations are carried on at a comparatively small expense. An adit level judiciously placed facilitates the drainage and ventilation of the mine; it also affords an easy access for the miners, and egress for the ore by means of wagons running on a tramroad, and propelled either by men or horses, thus saving the labour and expense of raising the products by either steam or water power. In addition to these advantages, the ore is delivered on the banks of a stream, the most convenient place for preparing it for the smelting-house; and should water be required for driving the crushing mills or other machinery, it can ordinarily be obtained from the higher course of the stream; consequently steam power is seldom required and rarely used in this district. The surface of the country in the immediate vicinity of the mines is for the most part wild moorland, and the miners reside in small villages lower down the valleys, and have to walk from two to four miles to and from the mine ... To some extent [this] counteracts the injurious effects of previous exposure to the vitiated atmosphere of the mines. Dr Peacock ... examined 250 miners ... [The most common disease was] miners' asthma. [The miners blame] bad air, powder reek,[nb 1] and stour ... The men have not usually to climb more than 15 to 30 fathoms [or 60 yards (55 metres)] ... He was struck with the most robust appearance of the miners, and the larger proportion of middle-aged and old men among them ... [Dr Peacock indicated a problem with ventilation and "choke damp".] ... In these northern districts, the rates of mortality are much higher among the mining than among the non-mining section of the male population. [In the 110 Northern England mines analysed:] the air was found to be pure or nearly so in 14 or 12.2 per cent, decidedly impure in 27 or 24.54 per cent, and extremely bad in 69 or 62.72 per cent ... In those mines the amount of oxygen was, in one instance, as low as 18.27 per cent, and the carbonic acid amounted in another to 2.26 per cent ... The men are not infrequently small farmers, with gardens attached to their cottages, and ground for the keep of a cow, which enables them to take milk, which they take underground ... The children are not employed to so great an extent at mines, and do not go underground at so early an age as in the South".[14]

Archaeological evidence

[edit]The visible evidence of mine works at Arn Gill includes a lead mine lodging shop which survives as a ruined building,[nb 2] and an elling hearth,[nb 3] chopwood kiln,[nb 4] or Q-pit,[nb 5] in the form of a shallow depression and curved pile of stones below the mine shop.[15][16]

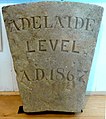

The Yorkshire Mine and Cave Group cleared out and rebuilt the entrance to Adelaide level in 2008–2010, but the inside of the mine is still vulnerable to collapse and flooding. The keystone now in the entrance arch is a replica. The original, engraved with the mine's name and date and discovered by the Cave Group in 1998, is in Swaledale Museum. The museum contains an exhibition related to local lead mining.[9][10]

-

Mine entrance with facsimile keystone

-

Original keystone, in Swaledale Museum, Reeth

-

Ruined lodging shop

Hill walking

[edit]Arn Gill is on various hill-walking routes in Swaledale, including one detailed by Swaledale Museum. The interior of Adelaide Level is unsafe, but there are photographs of the mine's interior in the museum.[9]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Powder reek is noxious fumes from explosives

- ^ A mine shop was the mine's office building. A mine lodging shop was the dormitory building where miners slept. The building could also function as both: see Historic England: Park Level mine shop.

- ^ An elling hearth was a stone hearth in a shallow depression for burning twigs and vegetation to make potash for processing wool. See DHER: elling hearth

- ^ A chopwood kiln was "a type of kiln, usually built into banking, with a stone lining that was used to produce white coal (dried wood) which was used as fuel in the lead smelting process". See DHER: chopwood kiln

- ^ A Q-pit was "A kiln in the form of a pit dug into the earth which was used for the production of white coal prior to the Industrial Revolution". See DHER Q pit

References

[edit]- ^ "Arn". nordicnames.de. Nordic Names. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ wikt:gill

- ^ "SD911992 or location N.391150, W.499250". streetmap.co.uk. Streetmap. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Metaliferrous mines of the Yorkshire Dales". nmrs.org.uk. Northern Mine Research Society. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Guy, Helen. "ArnGill and West Stonesdale mines". keld.omeka.net. Keld Resource Centre. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Gill, Mike (2004). Swaledale: Its Mines and Smelt Mills (2 ed.). London: Landmark. ISBN 9781843061311. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Fawcett, Edward R. (1 January 1985). Lead mining in Swaledale (1 ed.). Faust. ISBN 978-0948558009.

- ^ a b c "Swaledale Walk 1 - Muker to Adelaide Level". swaledalemuseum.org/. Swaledale Museum. 2019. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ a b Little, Tracy (Summer 2011). "The Adelaide Level" (PDF). Friends of Swaledale Museum Newsletter (11): 3. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Obituary: death of Major Waring's aunt". Berwickshire News and General Advertiser. British Newspaper Archive. 14 July 1925. p. 3 col.6. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Roe, Martin (2015). "Lead". outofoblivion.org.uk. Out of Oblivion. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Lead mining in the Yorkshire Dales: Early Mining: A Brief History". mylearning.org. My Learning. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b "The lead mines of North Yorkshire". Yorkshire Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 29 October 1864. p. 2 col.5. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Laurie, Tim (17 November 2011). "SWAAG ID 337". swaag.org. Swaledale and Arkengarthdale Archaeology Group. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Barker, L. (1978). "Memoirs 1978" (PDF). British Mining. 8. The Northern Mine Research Society Sheffield UK: 49–54. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- Clough, Robert T. (1980). "5, Swaledale". The Lead Smelting Mills of the Yorkshire Dales and Northern Pennines their architectural character, construction and place in the European tradition. Clough. ISBN 9780950644608. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Cooper, Edmund (2010). Muker: The Story of a Yorkshire Parish. UK: Hayloft. ISBN 9781904524779. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Plowright, Alan (2009). John Henry's Journeys Two Long Distance Walks in the Yorkshire Dales in 1879. UK: Moorfield Press. pp. 47–52. ISBN 9780956392909. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Arn Gill (North Yorkshire) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arn Gill (North Yorkshire) at Wikimedia Commons