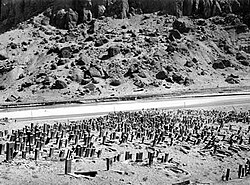

Armenian cemetery in Julfa

| Armenian cemetery in Julfa | |

|---|---|

The cemetery at Julfa as seen in a photograph taken in 1915 by Aram Vruyrian.  | |

| |

| Details | |

| Location | Julfa, Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, Azerbaijan |

| Coordinates | 38°58′27″N 45°33′53″E / 38.974172°N 45.564803°E |

| Type | public |

| No. of graves | 1648: 10,000 1903–04: 5,000 1998: 2,700 2006: 0 |

The Armenian cemetery in Julfa (Armenian: Ջուղայի գերեզմանատուն, Jughayi gerezmanatun)[1] was a cemetery near the town of Julfa (known as Jugha in Armenian), in the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan that originally housed around 10,000 funerary monuments.[2] The tombstones consisted mainly of thousands of khachkars—uniquely decorated cross-stones characteristic of medieval Christian Armenian art. The cemetery was still standing in the late 1990s, when the government of Azerbaijan began a systemic campaign to destroy the monuments.

Several appeals were filed by both Armenian and international organizations, condemning the Azerbaijani government and calling on it to desist from such activity. In 2006, Azerbaijan barred European Parliament members from investigating the claims, charging them with a "biased and hysterical approach" to the issue and stating that it would only accept a delegation if it visited Armenian-occupied territory as well.[3] In the spring of 2006, a journalist from the Institute for War and Peace Reporting who visited the area reported that no visible traces of the cemetery remained.[4] In the same year, photographs taken from Iran showed that the cemetery site had been turned into a military shooting range.[5] The destruction of the cemetery has been widely described by Armenian sources, and some non-Armenian sources, as an act of cultural genocide.[6][7][8]

After studying and comparing satellite photos of Julfa taken in 2003 and 2009, in December 2010 the American Association for the Advancement of Science came to the conclusion that the cemetery was demolished and leveled.[9]

History

[edit]Nakhchivan is an exclave which belongs to Azerbaijan. Armenia's territory separates it from the rest of Azerbaijan. The exclave also borders Turkey and Iran. Lying near the Aras River, in the historical province of Syunik in the heart of the Armenian plateau, Jugha gradually grew from a village to a city during the late medieval period. In the sixteenth century, it boasted a population of 20,000–40,000 Armenians who were largely occupied with trade and craftsmanship.[10] The oldest khachkars found at the cemetery at Jugha, located in the western part of the city, dated to the ninth to tenth centuries but their construction, as well as that of other elaborately decorated grave markers, continued until 1605, the year when Shah Abbas I of Safavid Persia instituted a policy of scorched earth and ordered the town destroyed and all its inhabitants removed.[11]

In addition to the thousands of khachkars, Armenians also erected numerous tombstones in the form of rams, which were intricately decorated with Christian motifs and engravings.[1] According to the French traveler Alexandre de Rhodes, the cemetery still had 10,000 well-preserved khachkars when he visited Jugha in 1648.[1] However, many khachkars were destroyed from this period onward to the point that only 5,000 were counted standing in 1903–1904.[1]

Scottish artist and traveler Robert Ker Porter described the cemetery in his 1821 book as follows:[12]

...a vast, elevated, and thickly marked tract of ground. It consists of three hills of considerable magnitude; all of which are covered as closely as they can be set; leaving the length of a foot between, with long upright stones; some as high as eight or ten feet; and scarcely any that are not richly, and laboriously carved with various commemorative devices in the forms of crosses, saints, cherubs, birds, beasts, &c besides the names of the deceased. The most magnificent graves, instead of having a flat stone at the feet, present the figure of a ram rudely sculpted. Some have merely the plain form; others decorate its coat with strange figures and ornaments in the most elaborate carving.

Vazken S. Ghougassian, writing in Encyclopædia Iranica, described the cemetery as the "until the end of the 20th century the most visible material evidence for Julfa’s glorious Armenian past."[13]

Destruction

[edit]Background

[edit]

Armenia first brought up charges against the Azerbaijani government for destroying khachkars in 1998 in the town of Julfa. Several years earlier, Armenia had supported the Armenians of Karabakh to fight for their independence in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan, in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. The war concluded in 1994 when a cease fire was signed between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh established the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, an internationally unrecognized but de facto independent state. Since the end of the war, enmity against Armenians in Azerbaijan has built up. Sarah Pickman, writing in Archaeology, noted that the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh to the Armenians has "played a part in this attempt to eradicate the historical Armenian presence in Nakhchivan."[2]

In 1998, Azerbaijan dismissed Armenia's claims that the khachkars were being destroyed. Arpiar Petrosyan, a member of the organization Armenian Architecture in Iran, had initially pressed the claims after having witnessed and filmed bulldozers destroying the monuments.[2]

Hasan Zeynalov, the permanent representative of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (NAR) in Baku, stated that the Armenian allegation was "another dirty lie of the Armenians." The government of Azerbaijan did not respond directly to the accusations but did state that "vandalism is not in the spirit of Azerbaijan."[14] Armenia's claims provoked international scrutiny that, according to Armenian Minister of Culture Gagik Gyurdjian, helped to temporarily stop the destruction.[4]

Armenian archaeologists and experts on the khachkars in Nakhchivan stated that when they first visited the region in 1987, prior to the breakup of the Soviet Union, the monuments had stood intact and the region itself had as many as "27,000 monasteries, churches, khachkars, tombstones" among other cultural artifacts.[4] By 1998, the number of khachkars was reduced to 2,700.[15] The old cemetery of Julfa is known to specialists to have housed as many as 10,000 of these carved khachkar headstones, up to 2,000 of which were still intact after an earlier outbreak of vandalism on the same site in 2002.[2]

Renewed claims in 2003

[edit]

In 2003, Armenians renewed their protests, claiming that Azerbaijan had restarted the destruction of the monuments. On December 4, 2002, Armenian historians and archaeologists met and filed a formal complaint and appealed to international organizations to investigate their claims.[15] Eyewitness accounts of the ongoing demolition describe an organized operation. In December 2005, The Armenian Bishop of Tabriz, Nshan Topouzian, and other Iranian Armenians documented more video evidence across the Araks river, which partially demarcates the border between Nakhchivan and Iran, stating that it showed Azerbaijani troops had finished the destruction of the remaining khachkars by using sledgehammers and axes.[2]

International response

[edit]Azerbaijan's government has faced a flurry of condemnation since the charges were first revealed. When the claims were first brought up in 1998, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) ordered that the destruction of the monuments in Julfa cease.[2] The complaints also brought forward similar appeals to end the activity by the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS).

Azerbaijan

[edit]In reaction to the charges brought forward by Armenia and international organizations, Azerbaijan has asserted that Armenians had never existed in those territories. In December 2005, Zeynalov stated in a BBC interview that Armenians "never lived in Nakhichivan, which has been Azerbaijani land from time immemorial, and that's why there are no Armenian cemeteries and monuments and have never been any."[2] Azerbaijan instead contends that the monuments were not of Armenian but of Caucasian Albanian origin.

In regard to the destruction, according to the Azerbaijani Ambassador to the United States, Hafiz Pashayev, the videos and photographs that were introduced did not show the identity of the people nor display what they are actually destroying. Instead, the ambassador asserts that the Armenian side started a propaganda campaign against Azerbaijan to draw attention away from the alleged destruction of Azerbaijani monuments in Armenia.[16] Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev also denied the charges, calling them "a lie and a provocation."[4]

From Google Earth's satellite view of the site, the Azeri phrase "Hər şey vətən üçün" can be seen written on the hillside where the cemetery used to reside.[17] These words roughly translate into English as "Everything is for the homeland."

European Union

[edit]In 2006, European parliamentary members protested to the Azerbaijani government when they were barred from inspecting the cemetery. Hannes Swoboda, an Austrian socialist MEP and committee member who was denied access to the region, commented that "If they do not allow us to go, we have a clear hint that something bad has happened. If something is hidden we want to ask why. It can only be because some of the allegations are true."[3] Doctor Charles Tannock, a conservative member of the European Parliament for Greater London, and others echoed those sentiments and compared the destruction to the Buddha statues destroyed by the Taliban in Bamyan, Afghanistan in 2001.[3][5] He cited in a speech a British architect, Steven Sim, an expert of the region, who attested that the video footage shot from the Iranian border was genuine.[18]

Azerbaijan barred the European Parliament because it said it would only accept a delegation if it visited Armenian-controlled territory as well. "We think that if a comprehensive approach is taken to the problems that have been raised," said Azerbaijani foreign ministry spokesman Tahir Tagizade, "it will be possible to study Christian monuments on the territory of Azerbaijan, including in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic."[3]

Council of Europe

[edit]Both Azerbaijan and Armenia are members of the Council of Europe. After several postponed visits, a renewed attempt was planned by inspectors of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe for August 29 – September 6, 2007, led by the British Labour politician Edward O'Hara. As well as Nakhchivan, the delegation planned to visit Baku, Yerevan, Tbilisi, and Nagorno Karabakh.[19] The inspectors planned to visit Nagorno-Karabakh via Armenia, and had arranged transport to facilitate this. However, on August 28, the head of the Azerbaijani delegation to PACE released a demand that the inspectors must enter Nagorno Karabakh via Azerbaijan. On August 29, PACE Secretary General Mateo Sorinas announced that the visit had had to be canceled, because of the difficulty in accessing Nagorno-Karabagh using the route required by Azerbaijan. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Armenia issued a statement saying that Azerbaijan had stopped the visit "due solely to their intent to veil the demolition of Armenian monuments in Nakhijevan."[20]

Iran

[edit]The government of Iran expressed concern over the destruction of the monuments and filed a protest against the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic's government (NAR).

United States

[edit]In April 2011, the newly appointed United States ambassador to Azerbaijan Matthew Bryza visited Nakhchivan but was inexplicably refused access to Julfa by Azerbaijani authorities.[21] Bryza had intended to investigate the cemetery but instead was told by government authorities that they would help facilitate a new trip in the coming months.[22] In a statement released by the US embassy in Baku, Bryza stated that "As I said at the time the cemetery destruction was reported, the desecration of cultural sites – especially a cemetery – is a tragedy, which we deplore, regardless of where it happens."[21]

In response to the statement, Aram Hamparian, the executive director of the Armenian National Committee of America (ANCA), called the ambassador's comments "Far too little, five years too late" and criticized him for not speaking out more forcefully and earlier against the destruction while he was still United States Deputy Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs in 2006.[23]

Other

[edit]Numerous non-Armenian scholars condemned the destruction and urged the Azerbaijan government to give a more complete account of its activities in the region. Adam T. Smith, an anthropologist and associate professor of anthropology at the University of Chicago, called the removal of the khachkars "a shameful episode in humanity's relation to its past, a deplorable act on the part of the government of Azerbaijan which requires both explanation and repair."[2] Smith and other scholars, as well as several United States Senators, signed a letter to UNESCO and other organizations condemning Azerbaijan's government.[24]

Australian Catholic University's Julfa Project

[edit]In 2013 the Australian Catholic University together with Manning Clark House, Yerevan State University and the Armenian Apostolic Church of the Holy Resurrection in Sydney, began a project to create a digital reconstruction of the destroyed Julfa Cemetery. The project, led by Dr Judith Crispin and Prof. Harold Short, is using 3D visualisation and virtual reality techniques to create an immersive presentation of the medieval khachkars and ram-shaped stones set in the original location. Julfa project is the custodian of many historical photographs and maps of the Julfa cemetery, including those taken by Argam Ayvazyan over a 25-year period. Presentations of Julfa Project's early results were held in Rome during 2016. The project, which will run until 2020, will result in permanent installations in Yerevan and Sydney. Other notable scholars working on the Julfa Project include archaeologist Hamlet Petrosyan, cultural historian Dickran Kouymjian, 3D visualisation expert Drew Baker, and Julfa cemetery expert Simon Maghakyan.[25]

2010 AAAS analysis of satellite photos

[edit]As a response to Azerbaijan barring on-site investigation by outside groups, on December 8, 2010, the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) released an analysis of high-resolution satellite photographs of the Julfa cemetery site taken in 2003 and 2009. The AAAS concluded that the satellite imagery was consistent with the reports from observers on the ground, that "significant destruction and changes in the grade of the terrain" had occurred between 2003 and 2009, and that the cemetery area was "likely destroyed and later leveled by earth-moving equipment."[9]

Criticism of international reaction

[edit]Armenian journalist Haykaram Nahapetyan compared the destruction of the cemetery with the destruction of cultural heritage by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamiyan by the Taliban. He also criticized the international community's response to the destruction of the cemetery in Julfa.[26] Simon Maghakyan noted the West condemned the Taliban destruction of the Buddhas and the Islamist destruction of shrines in Timbuktu during the 2012 Northern Mali conflict because "the violators of cultural rights in both instances are anti-Western, al-Qaeda-linked groups, and that alone seems to have merited the strong Western condemnation." He added, "otherwise, why has the West maintained its overwhelming silence regarding the complete destruction of the world’s largest medieval Armenian cemetery by Azerbaijan, a major energy supplier to, and arms purchaser from, the West?"[27]

Remaining khachkars

[edit]- Julfa khachkars at the Etchmiadzin Cathedral

-

c. 1576

-

c. 1602

-

16th century

-

16th century

-

c. 1602

Replicas

[edit]-

at the Geghard monastery

-

at Geghard

-

at Geghard

-

at the Saint John the Baptist Church in Yerevan

-

at St. John Church in Yerevan

-

at St. John Church in Yerevan

See also

[edit]- Armenian cultural heritage in Azerbaijan

- Armenians of Julfa

- Buddhas of Bamiyan

- Razgrad Incident

- List of destroyed heritage

- Mausoleum of Sidi Mahmoud Ben Amar

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Aivazian, Argam (1983). "Ջուղայի գերեզմանատուն (The Cemetery of Jugha)". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia Volume IX. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences. p. 550.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pickman, Sarah (30 June 2006). "Tragedy on the Araxes". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America.

- ^ a b c d Castle, Stephen (23 October 2011). "Azerbaijan 'flattened' sacred Armenian site". The Independent.

- ^ a b c d Abbasov, Idrak; Rzayev, Shahin; Mamedov, Jasur; Muradian, Seda; Avetian, Narine; Ter-Sahakian, Karine (27 April 2006). "Azerbaijan: Famous Medieval Cemetery Vanishes". Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

- ^ a b Maghakyan, Simon (November 2007). "Sacred Stones Silenced in Azerbaijan". History Today. 57 (11): 4–5.

- ^ Antonyan, Yulia; Siekierski, Konrad (2014). "A neopagan movement in Armenia: the children of Ara". In Aitamurto, Kaarina; Simpson, Scott (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 280.

By analogy, other tragic events or threatening processes are designated today by Armenians as "cultural genocide" (for example, the destruction by Azerbaijanis of the Armenian cemetery in Julfa)...

- ^ Ghazinyan, Aris (13 January 2006). "Cultural War: Systematic destruction of Old Julfa khachkars raises international attention". ArmeniaNow. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

...another "cultural genocide being perpetrated by Azerbaijan."

- ^ Uğur Ümit Üngör (2015). "Cultural genocide: Destruction of material and non-material human culture". In Carmichael, Cathie; Maguire, Richard C. (eds.). The Routledge History of Genocide. Routledge. p. 250. ISBN 9781317514848.

- ^ a b "High-Resolution Satellite Imagery and the Destruction of Cultural Artifacts in Nakhchivan, Azerbaijan". American Association for the Advancement of Science. 8 December 2010.

- ^ Ayvazyan, Argam (1983). "Ջուղա (Jugha)". Armenian Soviet Encyclopedia Volume IX. Yerevan: Armenian Academy of Sciences. pp. 549–550.

- ^ On this removal, see Edmund Herzig, "The Deportation of the Armenians in 1604–1605 and Europe's Myth of Shah Abbas I," in History and Literature in Iran: Persian and Islamic studies in Honour of P.W. Avery, ed. Charles Melville (London: British Academic Press, 1998), pp. 59–71.

- ^ Porter, Robert Ker (1821). Travels in Georgia, Persia, Armenia, ancient Babylonia, &c. &c. Volume 1. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown. p. 613.

- ^ Ghougassian, Vazken S. (15 September 2009). "Julfa i. Safavid period". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ "Azeris dismiss Iran's concern over Armenian monuments in Nakhchivan." BBC News in BBC Monitoring Central Asia. December 11, 1998. Retrieved April 16, 2007

- ^ a b "Armenian intellectuals blast 'barbaric' destruction of Nakhchivan monuments." BBC News in BBC Monitoring Central Asia. February 13, 2003. Retrieved April 16, 2007

- ^ "Will the arrested minister become new leader of opposition? Azerbaijani press digest." Regnum News Agency. January 20, 2006. Retrieved April 15, 2007.

- ^ "https://earth.google.com/web/@38.9741392,45.56530652,728.09189398a,842.52835806d,35y,0h,0t,0r" Google Earth. November 26, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Dr Charles Tannock. Cultural heritage in Azerbaijan Archived 2019-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. Speech delivered to the Plenary on February 16, 2006. The home page of Dr Charles Tannock, Member of the European Parliament for Greater London. Retrieved April 16, 2007.

- ^ S. Agayeva, "PACE Mission to Monitor Cultural Monuments" from Trend News Agency, Azerbaijan, dated August 22, 2007

- ^ Vladimir Karapetian, Spokesperson of Ministry of Foreign Affairs, responds to a question by “Armenpress” News Agency on the cancellation of the visit of the PACE subcommittee on cultural issues to the region from Armenian Ministry of Foreign Affairs dated August 29, 2007.

- ^ a b "U.S. Envoy Barred From Ancient Armenian Cemetery In Azerbaijan." RFE/RL. April 22, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ^ "US Ambassador Visits Nakhchivan, Calls for Respect for Cultural Sites April 21, 2011." Embassy of the United States of America, Baku. April 21, 2011.

- ^ "ANCA: Bryza’s Effort ‘Far too Little, Five Years too Late’ Archived 2014-10-17 at the Wayback Machine." Asbarez. April 21, 2011. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

- ^ Smith, Adam T. et al. A copy of the letter in PDF format.

- ^ "Julfa Cemetery Digital Repatriation Project". Julfaproject.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ Nahapetyan, Haykaram (27 April 2015). "Destroying Christian Cultural Heritage Sites: Don't Only Condemn ISIS, but Also These Globally Recognized Gov't". The Christian Post.

- ^ Maghakyan, Simon (16 August 2012). "Is Western Condemnation of Cultural Destruction Reserved Exclusively for Enemies?". Armenian Weekly. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- (in Armenian) Ayvazyan, Argam. Jugha. Yerevan: Sovetakan Grogh, 1984.

- Bevan, Robert. The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. London: Reaktion, 2006.

- Baltrušaitis, Jurgis and Dickran Kouymjian. "Julfa on the Arax and Its Funerary Monuments" in Études Arméniennes/Armenian Studies In Memoriam Haig Berberian. Lisbon: Galouste Gulbenkian Foundation, 1986.

- Maghakyan, Simon. "Sacred Stones Silenced in Azerbaijan." History Today. Vol. 57, November 2007.

- Dr. Haghnazarian, Armen and Wickmann, Dieter. "Destruction of the Armenian Cemetery at Djulfa," June 2007. Heritage at Risk, 2006/2007, ICOMOS.

- "Argam Ayvazyan: Spy–Researcher For Nakhichevan Armenian Culture ," interview by Andran Abramian, Cultural Property News, 27 March 2021.

Photo galleries

[edit]- Partial Views of Jugha Cemetery, a photo gallery by Research on Armenian Architecture

- [1], Argam Ayvazyan digital archive on the Julfa Project page

Documentary films

[edit]- Julfa by the Research on Armenian Architecture organization

- The New Tears of Araxes

Other films

[edit]Satellite imagery

[edit]- Satellite Images provided by the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

External links

[edit]- The Annihilation of the Armenian Cemetery in Jugha, a brochure by Research on Armenian Architecture

- The Julfa Project

- Djulfa Virtual Memorial and Museum

- Destruction of the Armenian Cemetery at Djulfa by International Council on Monuments and Sites

- Evidence of destruction in Turkey Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine by Armenian National Committee of Australia

- Satellite Images Show Disappearance of Armenian Artifacts in Azerbaijan Archived 2017-10-19 at the Wayback Machine. AAAS press release.

- When The World Looked Away: The Destruction Of Julfa Cemetery RFE/RL

- History of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

- Anti-Armenian sentiment in Azerbaijan

- Former cemeteries

- Armenian cemeteries

- Armenian Apostolic cemeteries

- Monuments and memorials in Azerbaijan

- Demolished buildings and structures in Azerbaijan

- Cemetery vandalism and desecration

- Cemeteries in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

- Armenia–Azerbaijan relations

- Azerbaijani war crimes

- Mass graves in Azerbaijan