Arianna in Creta

Arianna in Creta ("Ariadne in Crete", HWV 32) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel. The Italian-language libretto was adapted by Francis Colman from Pietro Pariati's Arianna e Teseo, a text previously set by Nicola Porpora in 1727 and Leonardo Leo in 1729.

Performance history

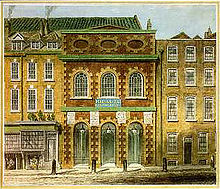

[edit]The opera was first given at the King's Theatre in London on 26 January 1734 and then presented in a revised version with dances added for Marie Sallé at Covent Garden Theatre on 27 November of the same year.[1]

As with all Baroque opera seria, Arianna in Creta went unperformed for many years, but with the revival of interest in Baroque music and historically informed musical performance since the 1960s,Arianna in Creta, like all Handel operas, receives performances at festivals and opera houses today.[2] Among other performances, Arianna in Creta was staged by the London Handel Festival in 2014[3] and performed in concert by the Handel Festival, Halle in 2018[4]

Roles

[edit]

| Role[1] | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 26 January 1734 |

|---|---|---|

| Arianna | soprano | Anna Maria Strada |

| Teseo | mezzo-soprano castrato | Giovanni Carestini |

| Carilda | contralto | Maria Caterina Negri |

| Alceste | mezzo-soprano castrato | Carlo Scalzi |

| Tauride | contralto | Margherita Durastanti |

| Minos | bass | Gustavus Waltz |

Synopsis

[edit]- Scene: Crete, in legendary antiquity.

Long before the action of the opera, King Minos of Crete fought a war with King Aegeus of Athens, who had killed Minos' baby son and carried away his baby daughter. The girl, however, had been brought up by an ally of Athens', King Archeus of Thebes, in the belief that she was his own child. Athens had to pay tribute to Crete as a term of ending the war – once every seven years seven Athenian youths and seven Athenian maidens had to be sent to Crete to be devoured by the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster that lurked in a labyrinth from which escape was all but impossible. The human sacrifice of Athenians can only be ended by a hero slaying the Minotaur and defeating the Cretan warrior Tauride. The Athenian hero Teseo is on the way to Crete, resolved to do this and end his peoples' suffering, and to join with Arianna, whom he loves, and whom Minos has demanded as a hostage to ensure that the Athenian young people will be sent for sacrifice.

Act 1

[edit]

The Athenians embark in Crete, alongside a stone tablet with the terms of the Athenian tribute inscribed on it. King Minos agrees to Teseo's request that Arianna be freed. Among the Athenian maidens sent to be sacrificed is Carilda, whose beauty is noticed by the Cretan champion Tauride; he instantly falls in love with her. Carilda is however secretly in love with Teseo and is interested in neither Tauride or the Athenian youth Alceste, who is also in love with Carilda. Teseo tells his beloved Arianna that he is determined to slay the Minotaur, making her fear for his safety, and also tells Alceste, who wants to rescue Carilda from a cruel death, that he is more fitted for the task.

In the temple of Jupiter, King Minos orders Alceste to draw the name of the first victim from an urn. Alceste is distressed when the name he draws from the vessel is that of his beloved Carilda. Teseo offers to go into the labyrinth to meet the Minotaur in her place, which Minos accepts, but makes Arianna jealous, believing Teseo must be doing this out of love for Carilda.

Act 2

[edit]

In a wood, Teseo ponders whether he should continue with his plan to try to kill the Minotaur, or refrain out of consideration to his beloved Arianna. He falls asleep, and has a vision of his destiny as the liberator of his people from cruel suffering. When he awakes, all indecision has been removed from his mind – he is determined to kill the monster. Alceste, like Arianna, is concerned that Teseo is acting out of love for Carilda, but Teseo assures him that he will never love anyone but Arianna and reveals to Alceste that Arianna is really the daughter of King Minos, but neither she nor the King know it.

Arianna overhears a conversation between Minos and the Cretan champion Tauride – to succeed, Teseo will have to slit the Minotaur's throat, find his way out of the labyrinth by using a ball of string to mark the way, and subdue Tauride in spite of his magic belt which gives him superhuman strength. Though still distressed by the thought that Teseo is attempting this to rescue Carilda whom he loves, Arianna passes this information on to Teseo.

Further misunderstandings reinforce Arianna in the mistaken belief that Teseo is in love with Carilda, and she accuses him of faithlessness.

At the entrance to the labyrinth, Carilda is about to be sent down to be devoured by the Minotaur, when Tauride appears and begs her to run away with him. She refuses. Alceste also appears however, kills the two guards and takes Carilda away. Minos is furious that she has escaped and blames Teseo for this. He orders Arianna to take Carilda's place as the first sacrifice to the monster. Arianna laments her fate.

Act 3

[edit]

Teseo descends into the labyrinth, marking his way by using a ball of string, and slays the Minotaur by stabbing it through the throat. He rescues Arianna and swears to her that he loves her.

Outside the palace, Teseo and Tauride are to meet in single combat. Teseo's first action is to tear Tauride's magic belt from his waist, after which Teseo easily vanquishes him.

King Minos announces that Teseo has fulfilled the conditions for ending the Athenian tribute. Teseo asks permission to marry Arianna, and Minos agrees on condition that her father gives his consent. Teseo reveals that Minos himself is Arianna's father, whereupon Minos happily gives the couple his blessing. Arianna and Teseo joyfully celebrate their love.

Inside the palace, a double betrothal is announced – the hero Teseo will marry his Arianna and Alceste has now been accepted by Carilda. All celebrate the fortunate turn of events.[5]

Context and analysis

[edit]

The German-born Handel, after spending some of his early career composing operas and other pieces in Italy, settled in London, where in 1711 he had brought Italian opera for the first time with his opera Rinaldo. A tremendous success, Rinaldo created a craze in London for Italian opera seria, a form focused overwhelmingly on solo arias for the star virtuoso singers. In 1719, Handel was appointed music director of an organisation called the Royal Academy of Music (unconnected with the present day London conservatoire), a company under royal charter to produce Italian operas in London. Handel was not only to compose operas for the company but hire the star singers, supervise the orchestra and musicians, and adapt operas from Italy for London performance.[6][7]

The Royal Academy of Music collapsed at the end of the 1728–29 season, partly due to the huge fees paid to the star singers. Handel went into partnership with John James Heidegger, the theatrical impresario who held the lease on the King's Theatre in the Haymarket where the operas were presented and started a new opera company with a new prima donna, Anna Strada. In this new venture, Handel had found that revisions of previous English language works such as Acis and Galatea and Esther, together with a new oratorio in English, Deborah, were extremely popular with audiences, albeit with the same Italian singers who were currently appearing in his operas on the same stage, including the star castrato Senesino, who had been a mainstay of Handel's operas for years, and whose pronunciation of the English texts caused some ridicule.[8][9]

Orlando, an Italian opera with a starring role by Handel for Senesino, was presented at the King's Theatre in January 1733, but in June of that year a notice appeared in the London press that Handel had dismissed Senesino.[10]: 208 In January 1733, before Handel had fired Senesino, there were already plans to start a second opera company in London to rival Handel's as John West, 2nd Earl De La Warr, wrote to the Duke of Richmond:

'There is a spirit got up against the Dominion of Mr. Handel, a subscription carry'd on, and Directors chosen, who have contracted with Senesino, and have sent for Cuzzoni, and Farinelli...'[11]

On June 15, several noble lords met with the approval of Frederick, Prince of Wales, to form a new opera company, the so-called "Opera of the Nobility" in open opposition to Handel, with London favourite Senesino again in leading roles and others of Handel's star singers in the new company.[12]

The new opera company gave its first performance on 29 December 1733, with an opera by Nicola Porpora, Arianna in Nasso, at Lincoln's Inn Theatre in London and with Senesino in a starring role, joined by another internationally celebrated castrato, Farinelli.[5] It is debated whether Handel may have chosen the subject of his next opera, Arianna in Creta, as a direct challenge to Porpora's piece at the new opera company, or whether Handel arrived at the subject before Porpora.[5] Handel's opera achieved a successful run of sixteen performances and Handel revived the work in his later season at Covent Garden Theatre.[1]

The diarist who kept what is known as "Colman's Opera Register" recorded: "Ariadne in Crete, a New Opera & very good & perform'd very often Sigr Carestino sung Surprisingly well: a new Eunuch – many times perform'd".[10]: 229

As a replacement for and rival to Senesino, Handel engaged an equally renowned castrato for the role of Teseo, Giovanni Carestini, of whom 18th century musicologist Charles Burney wrote:

“His voice was at first a powerful and clear soprano, which afterwards changed into the fullest, finest, and deepest counter-tenor that has perhaps ever been heard... Carestini’s person was tall, beautiful, and majestic. He was a very animated and intelligent actor, and having a considerable portion of enthusiasm in his composition, with a lively and inventive imagination, he rendered every thing he sung interesting by good taste, energy, and judicious embellishments. He manifested great agility in the execution of difficult divisions from the chest in a most articulate and admirable manner. It was the opinion of Hasse, as well as of many other eminent professors, that whoever had not heard Carestini was inacquainted with the most perfect style of singing.”[13]

Returning to the cast of a Handel opera premiere after an absence of nine years was Margherita Durastanti, who had worked with Handel in his early days in Italy and had been a member of his first London opera company.[5] Lady Bristol wrote in a letter after attending the second performance of Arianna in Creta: "I am just come home from a dull empty opera, tho' the second time; the first was full to hear the new man, who I can find out to be an extream good singer; the rest are all scrubbs except old Durastante, that sings as well as ever she did".[10]: 225

Charles Burney praised Arianna in Creta as testimony to Handel's "powers of invention, and abilities in varying the accompaniments throughout this opera with more vigour than in any former drama since the dissolution of the Royal Academy of Music in 1728".[13]

The opera is scored for flute, two oboes, bassoon, two horns, strings, and continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

Recordings

[edit]- Arianna in Creta - Orchestra of Patras. Conductor: George Petrou. Principal singers: Petros Magoulas (Minos), Irini Karaianni (Carilda), Marita Paparizou (Tauride), Mary-Ellen Nesi (Teseo), Theodora Baka (Alceste), Mata Katsuli (Arianna). Recording date: 2005. Label: MD&G Records – 7609 1375-2 (CD).[14]

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b c "List of Handel's works". Gfhandel.org. Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ^ "Handel:A Biographical Introduction". Handel Institute. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ "Dazzling coloratura delights in Handel's Arianna in Creta". Bachtrack.com/. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Bowdler, Sandra. "Simply outstanding: Arianna in Creta at the Halle Handel Festival". bachtrack.com. Retrieved 19 June 2018.[permanent dead link].

- ^ a b c d "Synopsis of Arianna in Creta". Handelhouse.org. Handel House Museum. Archived from the original on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ Dean, W. & J.M. Knapp (1995) Handel's operas 1704-1726, p. 298.

- ^ Strohm, Reinhard (20 June 1985). Essays on Handel and Italian opera by Reinhard Strohm. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521264280. Retrieved 2 February 2013 – via Google Books.

- ^ Burrows, Donald (2012). Handel (Master Musicians Series). Oxford University Press, USA; 2 edition. ISBN 978-0199737369.

- ^ Sherman, Bernard D: Inside Early Music, page 254. Oxford University Press US, 2003.

- ^ a b c Editorial Board of the Halle Handel Edition: Handel's Guide: Volume 4. German publishing house for music, Leipzig 1985, ISBN 3-7618-0717-1

- ^ "Handel Reference Database, 1733". Ichriss.ccarh.org. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Anthony Hicks: Handel. Orlando. L’Oiseau-Lyre 430 845-2, London 1991, p. 30 ff.

- ^ a b Burney, Charles (1957). A General History of Music, from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Dover. ISBN 978-0486222820.

- ^ "Recordings of Arianna in Creta". Operdis. org.uk. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- Sources

- Dean, Winton (2006), Handel's Operas, 1726-1741, Boydell Press, ISBN 1843832682 The second of the two volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel

- Warrack, John and West, Ewan (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 782 pages, ISBN 0-19-869164-5

External links

[edit]- Italian libretto Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Arianna in Creta: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- GFHandel.com review by Philippe Gelinaud of the Petrou recording