Argiletum

View of the Curia Julia, with the remains of the Argiletum, beneath Medieval layers, in the foreground. | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

|---|---|

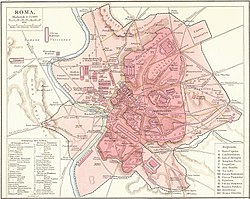

The Argiletum (Latin Argīlētum; Italian: Argileto) was a street in ancient Rome, which crossed the popular district of Suburra up to the Roman Forum, along the route of the current Via Leonina and Via della Madonna dei Monti.

On its eastern side, towards the Esquiline Hill, it branched off into the Vicus Patricius (now Via Urbana), which continued towards Porta Viminale, and the Clivus Suburanus (now Via in Selci), which climbed up to Porta Esquilina. On the western side, towards the Forum, it ended between the Basilica Aemilia and the Curia, but during the imperial age the first stretch was replaced by the Forum of Nerva, which however maintained a function of passageway and for this reason was also known as Forum Transitorium.

The name of the street could derive from the clay (Latin Argilla) carried by the waters that descended from the surrounding hills and then conveyed into the Cloaca Maxima. However, Varro claimed that the etymology of the term was connected with the name of a Greek scoundrel (see below).[1][2]

The Argiletum was the street of the booksellers and is mentioned by many ancient authors such as Horace, Martial and Seneca, who have also handed down the names of their trusted suppliers.

History

[edit]As it originally passed between the Comitium and the Basilica Pauli, the Argiletum was eventually absorbed by the construction of the Imperial fora from the time of Julius Caesar onwards. Given this encroachment, the limits of the street were defined differently in various periods.

Livy indicates that the Temple of Ianus Geminus was located ad infimum Argiletum (Liv. 1.19.1).[3] Another of the landmarks excavated in the area was a quadrifrons, which was located at the juncture of the Roman Forum, the Argiletum and the Forum of Caesar.[4] It is suggested that a second arch or a temple was also constructed somewhere on the Argiletum, possibly close to the Temple of Ianus.[4]

Paths that were found in the Alta Semita and the domus on the Oppian and Caelian hills converged onto the Argiletum, making it a principal node of public space particularly during the Flavian rule.[5]

By the time of Martial (died about AD 103), the Argiletum had become a seedy district filled with taverns and brothels.[6] However, this reputation may not reflect the actual status of the residents since the population was constituted by a mix of elite and nonelite, side by side.[7]

Myth

[edit]According to the myth, the tomb of a certain Argus was located in the Argiletum.[8]

Evander, son of the god Mercury and of the nymph Carmenta, had settled in Italy with a group of Arcadians from the city of Argos.[9] A certain Argos came to his court, plotting to kill Evander and take possession of his kingdom. Evander's followers discovered his intentions and, without their lord knowing it, killed Argos. However, out of respect for the inviolable rights of hospitality, Evander honored Argos with a magnificent funeral and erected a tomb for him in a place that was later called Argiletum, which means "death of Argos".[10]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Varro, De Lingua Latina 5.157.8 http://latin.packhum.org/loc/684/1/17/7101-7110

- ^ "Storia". www.urbana.roma.it. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ Ovid; Thomas Keightley (1848). Ovid's Fasti; with introduction, notes, and excursus. By T. Keightley. Second edition ... considerably improved. Whittaker and Company. pp. 226–.

- ^ a b Bradley, Mark (2012). Rome, Pollution and Propriety: Dirt, Disease and Hygiene in the Eternal City from Antiquity to Modernity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 9781107014435.

- ^ Martin-McAuliffe, Samantha L.; Millette, Daniel M. (2017-12-06). Ancient Urban Planning in the Mediterranean: New Research Directions. Routledge. ISBN 9781317181323.

- ^ Martial 1.2.7-8; 1.3.1; 1.117.9-12; 2.17

- ^ Mignone, Lisa Marie (2016). The Republican Aventine and Rome's Social Order. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780472119882.

- ^ Dizionario mitologico-storico-poetico at Google Books

- ^ Livy (Ab Urbe condita libri, I, 7); Ovid (Fasti, I, 470 et seq.)

- ^ Virgil. Aeneid. Vol. book VIII.