Are Castle

| Are Castle | |

|---|---|

Burg Are | |

| Altenahr | |

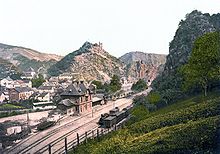

Ruins of Are Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50°31′02″N 6°59′41″E / 50.517361°N 6.99472°E |

| Type | hill castle |

| Code | DE-RP |

| Height | 240 m above sea level (NHN) |

| Site information | |

| Condition | ruin |

| Site history | |

| Built | c. 1100 |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | counts |

Are Castle (pronounced "Ahr-er", German: Burg Are) is the ruin of a hill castle that stands at a height of 240 m above sea level (NHN) above the village of Altenahr in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. It was built around 1100 by Count Dietrich I of Are and is first recorded in 1121.

Since 1965 the Are Gymnasium – a local grammar school – in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler has borne the name which is derived from the castle and its eponymous noble family.

Design

[edit]The plan of the castle is rectangular. As well as parts of the outer ward and a gate – the so-called Gymnicher Porz – remains of the defensive wall have survived. In addition, on the southern side of the site, is an old gate tower (also called the Schellenturm), as well as the ruins of the palas, which once had a heated bishop's chamber. The first bergfried probably stood on the pointed dome of rock in its northern corner. North of that are extensive remains of the Romanesque castle chapel dating to the 12th century.

Gymnicher Porz gatehouse

[edit]

Below Are Castle lie the remains of the Gymnicher Porz, Porz standing for Pforte or "portal". This was the lower gateway on the access road to the castle which, in combination with a wall, barred the way to the castle hill. The structure comprised a gatehouse over the access road, an attached castle house (Burghaus), with a basement and two floors housing living accommodation, and an attached tower. It took its name from the House of Gymnich. Several members of the family held the castle in fief (they were ‘’Pfandnehmer’’) in the 14th and 16th centuries. It is suspected that the gate system was built during this time. From time to time the Gymnicher Porz was an independent fief (Burglehen) of the House of Gymnich.

Conservation

[edit]From 1997 to 1999 the ruins were made safe at a high financial cost and classed as a protected monument. Since then they have been open to the public once more. The conservation work that began in March 1997 had the primary purpose of protecting traffic. There was a risk of rocks and stones from the site falling onto the federal highway. The construction material was transported to the castle site on a cable suspended from a Hughes 500 helicopter. After 30 flights the laden helicopter crashed on 9 April 1997 because the cable caught on its skids. The pilot received fatal injuries.[1]

In autumn 1997 the 22-metre (72 ft) long palas wall and its two side walls were restored. To guarantee the stability of the walls, 65 anchors were driven up to 14 metres (46 ft) deep into the slate rock.

History

[edit]

In 1246 Count Frederick of Hochstaden, provost of Xanten, with the assent of his brother Conrad of Are-Hochstaden gifted the county and its castles - Are, Hardt and Hochstaden – to the Archbishopric of Cologne. Its expansion with a surrounding enceinte was carried out during the period of Electoral Cologne in the 14th and 15th centuries in order to protect the Electorate's estates in the Ahr region. In the 16th and 17th centuries there were only minor changes to the castle in the form of repairs and replacement buildings. Periodically the castle was also used as a gaol in which the archbishops of Cologne incarcerated their enemies. For a long time Are Castle was a spiritual and cultural centre for the whole area.

Increasingly often, the archbishops of Cologne enfeoffed Are Castle with the district (Amt) of Altenahr. The liegemen were installed as Amtmännern and most of the also lived at the castle. Over a long time the castle fell into a poor state of repair because the vassals did not carry out the necessary work. One exception was the period of Henry of the Horst, who died in 1625.

In 1690 the castle was captured by French troops after a nine-month siege. The castle was badly damaged by shelling. In 1697 the French withdrew, but occupied the castle again during the War of the Spanish Succession that began in 1701. In 1706 the castle was taken over by Electoral Cologne forces and the area became unsafe. For this reason Prince Elector Joseph Clemens of Bavaria had the walls blown up in 1714 with the agreement of the villagers. Since then the castle has been a ruin. Reusable materials such as wood and stone were used as construction materials for the rebuilding of the district house (Amtshaus) at the foot of the castle hill.

-

The castle and Gymnicher Porz around 1830

-

The castle and gateway today from a similar standpoint

-

Inner ward

-

Ruins of the castle house of the Gymnicher Porz with the remains of the chimney

-

Castle chapel

The counts of Are

[edit]A Sigewin of Are, Archbishop of Cologne is mentioned in the records as early as 1087, but Dietrich I of Are is viewed as the primogenitur of the House of Are. The comital family named themselves after the river Ahr, whose surrounding area they owned. In 1140 the family divided into the lines of Are-Hochstaden and Are-Nürburg. Members of the family include:

- Gerhard of Are, from 1124 to 1169 provost of Bonn's Cassius foundation (Cassius-Stift), who had the Bonn Minster church enlarged.

- Frederick II of Are, 1152 to 1168 Bishop of Münster

- Lothar of Hochstaden, 1192/93 Bishop of Liège

- Dietrich II of Are, 1197 to 1212 Bishop of Utrecht

- Conrad of Hochstaden, from 1238 to 1261, Archbishop of Cologne and builder of Cologne Cathedral.

Literature

[edit]- Ignaz Görtz: "Wo sie am höchsten ragen, the Felsen der Ahr …" Beitrag zur Baugeschichte der Burg Are. In: Kreisverwaltung Ahrweiler (publ.): Heimatjahrbuch für den Kreis Ahrweiler 1961. Schiffer, Rheinberg, 1961, ISSN 0342-5827, pp. 94–98 (online).

- Ignaz Görtz: Inventaraufnahme auf Burg Altenahr im Jahre 1625. In: Kreisverwaltung Ahrweiler (publ.): Heimatjahrbuch für den Kreis Ahrweiler 1963. Schiffer, Rheinberg, 1963, ISSN 0342-5827, pp. 133–135 (online).

- Christine Schulze: Millionen für the Burg Are. In: Kreisverwaltung Ahrweiler (publ.): Heimatjahrbuch des Kreises Ahrweiler 2000. Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler, 1999, ISSN 0342-5827, pp. 47–50 (online).

- Joachim Gerhardt, Heinrich Neu: Kunstdenkmäler des Kreises Ahrweiler. 1. Halbband. L. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1938, pp. 146–156.