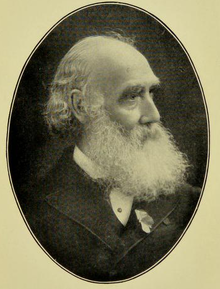

Archibald Hunter (hydrotherapist)

Archibald Hunter | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 January 1813 |

| Died | 26 August 1894 |

| Occupation | Hydrotherapist |

Archibald Hunter (7 January 1813 – 26 August 1894) was a Scottish hydrotherapist, naturopath and writer.

Biography

[edit]Hunter was born in Glasgow on 7 January 1813.[1] During his youth he worked for his father as a cabinet maker and took charge of the business at the age of nineteen. He became interested in hydrotherapy as a young man and joined the Glasgow Hydropathic Society. He opened his own hydropathic practice at 305 St. Vincent Street.[1] He obtained an old mansion on Gilmore Hill outside of Glasgow and turned it into a hydropathic establishment which could accommodate thirty patients. It became known as the Bridge of Allan Hydropathic Establishment.[1] The institute promoted the use of fresh air, water and a vegetarian diet.[2]

He remained at his institution as the manager and medical adviser until his retirement in 1894. Hunter had no medical training but was awarded a degree of Doctor by the New York Hydropathic and Physiological School in recognition of his services to hydrotherapy.[1] He authored a popular domestic guide on hydrotherapy which passed into its thirteenth edition in 1899.[3]

Hunter died in August 1894 only four weeks into his retirement.[1] After his death, his wife Agnes Hunter took over his institute and put a heavy emphasize on a restricted vegetarian diet and other dietary measures which was considered too extreme. The institute lost financial support and in 1914 was bought by Henry Lunn who aimed to convert it into a sporting hotel.[4]

Family

[edit]His second wife Annie Steedman Hunter (also known as Agnes Hunter) was an anti-vaccinationist who also promoted hydrotherapy and vegetarianism.[2][3][5] She died in 1914.[6]

Two of Hunter's sons, Francis and William qualified as medical doctors from Glasgow University. Francis died from tuberculosis aged 27 in Australia. His son William Bell was Medical Superintendent at Smedley Hydro and authored an article on Hydrotherapy for the ninth edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica in 1881.[6]

Selected publications

[edit]- Hydropathy: Its Principles and Practice (1881)

- Health, Happiness, and Longevity (1885)

- The Head: Its Relation to the Body in Health and Disease (1886)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Metcalfe, Richard. (1912). The Rise and Progress of Hydropathy in England and Scotland. London: Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. pp. 164–169

- ^ a b "Meet the vegetarian anti-vaxxers who led the smallpox inoculation backlash in Victorian Britain". theconversation.com. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ a b Marland, Hilary; Adams, Jane (2009). "Hydropathy at home: the water cure and domestic healing in mid-nineteenth-century Britain". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 83 (3): 499–529. doi:10.1353/bhm.0.0251. PMC 2774269. PMID 19801794.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Durie, Alastair J. (2012). "A fading movement: hydropathy at the Scottish Hydros 1840–1939". Journal of Tourism History. 4 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1080/1755182X.2012.671374. S2CID 154170181.

- ^ "New Publications". The Vegetarian Magazine. 14 (1): 35–36. 1910.

- ^ a b Warwick, Alex; Clifford, David; Wadge, Elisabeth; Willis, Martin. (2006). Repositioning Victorian Sciences: Shifting Centres in Nineteenth-Century Thinking. Anthem Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781843317517