Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia

Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1860–1862 | |||||||||

| Motto: Independencia y libertad | |||||||||

| Anthem: Himno a Orélie Antoine I (Wilhelm Frick Eltze, 1864[1]) | |||||||||

Location of the claimed territory of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia, in Chile and Argentina | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized State | ||||||||

| Capital | Perquenco (claimed) 38°25′S 72°23′W / 38.41°S 72.38°W | ||||||||

| Common languages | Mapudungun | ||||||||

| Government | Elective Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 1860–1862 | Orélie-Antoine I (Aurelio Antonio I) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | November 17/20, 1860 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | January 5, 1862 | ||||||||

| Currency | Araucanía and Patagonia peso (since 1874) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia (Spanish: Reino de la Araucanía y de la Patagonia; French: Royaume d'Araucanie et de Patagonie), sometimes referred to as Kingdom of New France (French: Royaume de Nouvelle-France), was an unrecognized state[2][3] declared by two ordinances on November 17, 1860 and November 20, 1860 from Antoine de Tounens, a French lawyer and adventurer, who claimed that the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia did not depend on any other states and proclaimed himself[4][5][6] king of Araucanía and Patagonia. He had the support of some Mapuche lonkos around a small area in Araucanía, who thought they could help maintain independence from the Chilean and Argentine governments.

Arrested on January 5, 1862 by the Chilean authorities, Antoine de Tounens was imprisoned and declared insane on September 2, 1862 by the court of Santiago[7] and expelled to France on October 28, 1862.[8] He later tried three times to return to Araucanía to reclaim his kingdom without success.

History

[edit]

In 1858, Antoine de Tounens, a former lawyer in Périgueux, France, who had read the book La Araucana by Alonso de Ercilla, decided to go to Araucanía, inspired to become its king after reading the book. He landed at the port of Coquimbo in Chile and met some loncos (Mapuche tribal leaders) after arriving South to the Biobío. He promised them some arms and the help of France to maintain their independence from Chile. The Indians elected him Great Toqui, Supreme Chieftain of the Mapuches,[9][10] possibly in the belief that their cause might be better served with a European acting on their behalf.[citation needed]

On November 17, 1860, and November 20, 1860, the self-proclaimed sovereign[4][11][6][12][13] proclaimed via two decrees that the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia did not need to depend on any other states and that the Kingdom of Araucanía is founded with himself as monarch under the name King Orélie-Antoine I. He declared Perquenco capital of his kingdom, created a flag, and had coins minted for the nation under the name of Nouvelle France.[citation needed]

He writes in his Memoirs in 1863 "I took the title of king, by an ordinance of November 17, 1860, which established the bases of the hereditary constitutional government founded by me [...] On November 17, I returned to Araucanía to be publicly recognized as king, which took place on December 25, 26, 27 and 30. Weren't we, the Araucanians, free to bestow power on me, and I to accept it?"[14]

The supposed founding of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia led to the Occupation of Araucanía by Chilean forces. Chilean president José Joaquín Pérez authorized Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez, commander of the Chilean troops, to arrest Antoine de Tounens on January 5, 1862. Tounens was then imprisoned and declared insane on September 2, 1862, by the court of Santiago[7] and expelled to France on October 28, 1862.[8]

Attempts to return and fears of French intervention

[edit]In a 1870 meeting of Saavedra with Mapuche lonkos at Toltén, Mapuche chiefs revealed to Saavedra that Antoine de Tounens was once again at Araucanía.[15] Upon hearing that his presence in Araucanía had been revealed Orélie-Antoine de Tounens fled to Argentina, having however promised Quilapán to obtain arms.[15] There are some reports that a shipment of arms seized by Argentine authorities at Buenos Aires in 1871 had been ordered by Orélie-Antoine de Tounens.[16] A French warship, d'Entrecasteaux, that anchored in 1870 at Corral, drew suspicions from Saavedra of some sort of French interference.[15] Accordingly there may have been substance to these fears as information was given to Abdón Cifuentes in 1870 that an intervention in favour of the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia against Chile was discussed in Napoleon III's Conseil d'Êtat.[17]

On August 28, 1873, the Criminal Court of Paris ruled that Antoine de Tounens, first "king of Araucanía and Patagonia", did not justify his claim to the status of sovereignty.[18] He died in poverty on September 17, 1878, in Tourtoirac, France, after years of fruitlessly struggling to regain his kingdom.[19][verification needed]

After de Tounens (1873–present)

[edit]Historians Simon Collier and William F. Sater describe the Kingdom of Araucanía as a "curious and semi-comic episode".[19] According to travel writer Bruce Chatwin, the later history of the "kingdom" belongs rather to "the obsessions of bourgeois France than to the politics of South America."[20] A French champagne salesman, Gustave Laviarde, impressed by the story, decided to assume the vacant throne as Aquiles I.[21] He was appointed heir to the throne by Orélie-Antoine.[22] The pretenders to the throne of Araucanía and Patagonia have been called monarchs and sovereigns of fantasy,[23][24][25][26][27] "having only fanciful claims to a kingdom without legal existence and having no international recognition".[28] Therefore the "throne of Araucanía" is sometimes the subject of disputes between "pretenders",[29] some journalists wrote : "The memory of the French adventurer Orélie-Antoine, self-proclaimed king in 1860, and the defense of the rights of the Mapuches guide the action of this strange symbolic monarchy"[30] and "The intensification of the Mapuche conflict in recent years has given a new purpose to the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia, long considered an absurdity by French society."[31]

Mapuche writer Pedro Cayuqueo considers the kingdom a lost opportunity and speculates that, in a French-ruled Araucanía, the Mapuche would have rights similar to that of the Kanak people, who were given the possibility of independence from France in a 2018 referendum.[32][33]

Pretenders to the throne after Antoine de Tounens

[edit]Antoine de Tounens had no children, but since his death in 1878, some French citizens without any familial relations to him declared to be pretenders to the "throne of Araucanía and Patagonia". Whether the Mapuche themselves accept this or are even aware of it, is unclear.[34]

Sovereign

| No. | image | title | Given name

(birth- Death) |

Reign | Ref. | Other information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Orélie-Antoine I | Orélie-Antoine de Tounens (1825–1878) |

1860-1862 | Antoine de Tounens, He founded the kingdom of Araucanía by an ordinance of 17 November 1860 and proclaimed himself or was proclaimed king by the Mapuche populations. He took the name of Orélie-Antoine I. He appointed French and Mapuche ministers. Overthrown by Chilean and Argentine soldiers, he returned to France where he kept his titles until his death. |

List of pretenders to the throne and heads of the royal house of Araucanía and Patagonia

| No. | Image | Title | Given name (Birth–Death) |

Reign | Ref. | Other information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Orélie-Antoine I | Orélie-Antoine de Tounens (1825–1878) |

1862–1878 | ||

| 2 |

|

Achille I | Gustave-Achille Laviarde (1841–1902) |

1878–1902 | [35][36] | Secretary of the preceding.

Titled Prince of Aucas and Duke of Kialeon by Antoine de Tounens he declared himself in March 1882 successor to Antoine de Tounens |

| 3 |

|

Antoine II | Antoine-Hippolyte Cros (1833–1903) |

1902–1903 | [35][37] | Titled Duke of Niacalel and appointed Keeper of the Seals of the Kingdom of Araucanía by Achille Laviarde |

| 4 |

|

Laure Therese I | Laure-Therese Cros (1856–1916) |

1903–1916 | Daughter of | |

| 5 |

|

Antoine III | Jacques Antoine Bernard (1888–1952) |

1916–1952 | abdicated in favour of prince Philippe | |

| 6 |

|

Prince Philippe | Philippe Paul Alexandre Henri Boiry (1927–2014) |

1952–2014 | [37] | |

| - |

|

Regent Philippe de Lavalette | Philippe de Lavalette | 2014-2014 | Regent of the kingdom until the election of the successor by the Council of Regency. | |

| 7 |

|

Antoine IV | Jean-Michel Parasiliti di Para (1942–2017) |

2014–2017 | ||

| - |

|

Regent Sheila Rani | Sheila Rani | 2017-2018 | Regent of the kingdom until the election of the successor by the Council of Regency. | |

| 8 |

|

Frédéric I | Frédéric Rodriguez-Luz (1964–) |

2018–2024 | Disputed

(since 2023) | |

| - |

|

Regent Muhammad Luqman | Muhammad Luqman | 2024 –present | Regent of the kingdom until the election of the successor by the Council of Regency. |

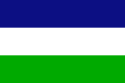

Flag

[edit]Sources[who?] are unclear on what flag, if any, Tounens used, as his "government" was never formalized. Some sources say a green-blue-white flag was used, and other sources say a blue-white-green.[38] The green-blue-white variant of the flag was probably only hoisted by Orélie in Araucanía for a few weeks. The blue-white-green version was designed by Orélie in exile in France, and is still used by pretenders to the throne after his death.[39]

-

Modern hypothetical flag based on description of the flag hoisted by Orélie-Antoine de Tounens in Araucanía.

-

The later version designed in France; the most common interpretation of the flag.

In popular culture

[edit]Television

[edit]- 1990: Le Roi de Patagonie, TV mini-series directed by Georges Campana and Stéphane Kurc

- 1991: Le Jeu du roi, TV film directed by Marc Evans

- 2017: Rey is based on this incident.[40]

Novel

[edit]- Jean Raspail, Moi, Antoine de Tounens, roi de Patagonie (I, Antoine of Tounens, King of Patagonia) (1981)

Video games

[edit]- In the Hearts of Iron IV expansion pack "Trial of Allegiance", a player may play as Chile and, via according focus tree, restore the Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ El himno, en realidad, es una parte de una opereta que satiriza a Orélie. THE OPERA OF GUILLERMO FRICK AND THE ARAUCANIAN NATIONAL ANTHEM. Consultado 11/05/2016

- ^ Verónica Méndez Montero; Carolina Santelices Ariztía; Rodrigo Martínez Iturriaga (2009). Historia, Geografía y Ciencias Sociales 2° Educación Media (in Spanish). Santillana. ISBN 978-956-15-1557-4.

- ^ Youkee, Mat (May 21, 2018). "Why the lost kingdom of Patagonia is a live issue for Chile's Mapuche people". The Guardian. Retrieved May 6, 2022.

- ^ a b Hosne, Roberto (September 10, 2001). Patagonia: History, Myths and Legends. Duggan-Webster. ISBN 9789879862605 – via Google Books.

- ^ Trigger, Bruce G.; Washburn, Wilcomb E.; Adams, Richard E. W.; Salomon, Frank; Schwartz, Stuart B.; MacLeod, Murdo J. (September 10, 1996). The Cambridge History of the Native Peoples of the Americas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521630764 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Serrano, Carlos Foresti; Löfquist, Eva; Foresti, Alvaro; Medina, María Clara (September 10, 2001). La narrativa chilena desde la independencia hasta la Guerra del Pacífico: Costumbres e historia, 1860-1879. Editorial Andres Bello. ISBN 9789561316980 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Scheina, Robert L. (September 10, 2003). Latin America's Wars: The age of the caudillo, 1791-1899. Brassey's, Incorporated. ISBN 9781574884494 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Lagrange, Jacques (September 10, 1990). Le roi français d'Araucanie. PLB. ISBN 9782869520219 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wendt, Herbert (September 10, 1966). "The red, white, and black continent: Latin America, land of reformers and rebels". Garden City, N. Y., Doubleday – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jean-François., Gareyte (2016). Le rêve du sorcier : Antoine de Tounens, roi d'Araucanie et de Patagonie : une biographie. Tome I. Mollier, Pierre. Périgueux: La Lauze. ISBN 9782352490524. OCLC 951666133.

- ^ Correa, Jorge Fernández (September 10, 2009). El naufragio del naturalista belga. RIL Editores. ISBN 9789562846806 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Procesos". Corporación Editora Nacional. September 10, 2000 – via Google Books.

- ^ Devoto, Fernando (September 10, 2001). Emigration politique : une perspective comparative: Italiens et Espagnols en Argentine et en France, XIXe-XXe siècles. Harmattan. ISBN 9782747516778 – via Google Books.

- ^ Tounens, Orllie Antoine C. de (September 10, 1863). "Orllie-Antoine 1er, roi d'Araucanie et de Patagonie: son avénement au trône et sa captivité au Chili, relation écrit par lui-même" – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Bengoa 2000, pp. 227-230.

- ^ Bengoa 2000, p. 187.

- ^ Cayuqueo 2020, p. 59

- ^ Le XIXe siècle : journal quotidien politique et littéraire. 1873.

- ^ a b Collier, Simon; Sater, William F.: A history of Chile, 1808–2002. Cambridge University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-521-82749-3, p.96.

- ^ Chatwin, Bruce: In Patagonia. Random House, 2012, ISBN 9781448105618, p. 25.

- ^ Minnis, Natalie: Chile Insight. Langenscheidt Publishing, 2002, ISBN 981-234-890-5, p. 41.

- ^ Nicholas Shakespeare, The Men who would be King, 1983.

- ^ Fuligni, Bruno (1999). Politica Hermetica Les langues secrètes. L'Age d'homme. p. 135. ISBN 9782825113363.

- ^ Journal du droit international privé et de la jurisprudence comparée. 1899. p. 910.

- ^ Montaigu, Henri (1979). Histoire secrète de l'Aquitaine. A. Michel. p. 255. ISBN 9782226007520.

- ^ Lavoix, Camille (2015). Argentine : Le tango des ambitions. Nevicata. ISBN 9782511040072.

- ^ Bulletin de la Société de géographie de Lille. 1907. p. 150.

- ^ Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux. ICC. 1972. p. 51.

- ^ Eschapasse, Baudouin (December 6, 2018). "Querelle dynastique au royaume d'Araucanie". Le Point (in French). Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Bassets, Marc (June 1, 2018). "Federico I, un nieto de exiliado republicano en el 'trono' de la Patagonia". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ "'We are hostages': indigenous Mapuche accuse Chile and Argentina of genocide". the Guardian. April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ Cayuqueo 2020, p. 55

- ^ Cayuqueo 2020, p. 60

- ^ Peregrine, Anthony (February 5, 2016). "France's forgotten monarchs". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ a b Piccirilli, R: "Diccionario histórico argentino", p. 260. Ediciones Historicas, 1953.

- ^ Sociedad Chilena de Historia y Geografía, Archivo Nacional (Chile): "Revista chilena de historia y geografía", p. 277. Impr. Universitaria, 1931.

- ^ a b Braun Menéndez, A: "Pequeña historia patagónica", p. 128. Emecé Editores, 1959.

- ^ Menéndez, Armando Braun (1973). "El reino de Araucanía y Patagonia".

- ^ "Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia (1860-1862)".

- ^ Clarke, Cath (January 5, 2018). "Rey review – dreamlike drama about a man who would be king". The Guardian. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- Bibliography

- Bengoa, José (2000). Historia del pueblo mapuche: Siglos XIX y XX (in Spanish) (Seventh ed.). LOM Ediciones. ISBN 956-282-232-X.

- Cayuqueo, Pedro (2020). Historia secreta mapuche 2 (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Catalonia. ISBN 978-956-324-783-1.

External links

[edit]- History of Patagonia

- Former political divisions related to Argentina

- 1860s in Chile

- Araucanía Region

- Mapuche history

- Former monarchies

- Former unrecognized countries

- 19th-century colonization of the Americas

- States and territories established in 1860

- 1860 establishments in South America

- States and territories disestablished in 1862

- 1862 disestablishments in South America