Apostasy in Islam by country

| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

The situation for apostates from Islam varies markedly between Muslim-minority and Muslim-majority regions.[1] In Muslim-minority countries, "any violence against those who abandon Islam is already illegal". But in some Muslim-majority countries, religious violence is "institutionalised", and (at least in 2007) "hundreds and thousands of closet apostates" live in fear of violence and are compelled to live lives of "extreme duplicity and mental stress."[2]

Afghanistan

[edit]Article 130 of the Afghan Constitution requires its courts to apply provisions of Hanafi Sunni fiqh for crimes of apostasy in Islam. Article 1 of the Afghan Penal Code requires hudud crimes be punished per Hanafi religious jurisprudence. Prevailing Hanafi jurisprudence, per consensus of its school of Islamic scholars, prescribes death penalty for the crime of apostasy. The apostate can avoid prosecution and/or punishment if he or she confesses of having made a mistake of apostasy and rejoins Islam.[3] In addition to death, the accused can be deprived of all property and possessions, and the individual's marriage is considered dissolved in accordance with Hanafi Sunni jurisprudence.[4] Al-Qaeda has viewed the United States as a leading apostate nation.[5]

In February 2006, the homes of Afghan converts to Christianity were raided by police.[6][page needed] The next month converts to Christianity were arrested and jailed. Abdul Rahman, who had "lived outside Afghanistan for 16 years and is believed to have converted to Christianity during a stay in Germany", was charged with apostasy and threatened with the death penalty. His case sparked international protest from many Western countries.[7][8] Charges against Abdul Rahman were dismissed on technical grounds of being "mentally unfit" (an exemption from execution under sharia law) to stand trial[7] by the Afghan court after intervention by the president Hamid Karzai. He was released and left the country[6] after the Italian government offered him political asylum.[8]

In Afghanistan, I've seen how someone was nearly beaten to death for blasphemy. In Kabul they are stoning apostates.

Another Afghan convert, Sayed Mussa, was threatened with life imprisonment for apostasy but spent several months in jail, and was released in February 2011, after "months of quiet diplomacy" between the US and Afghan governments. According to a senior Afghan prosecutor, he was released "only after finally agreeing to return to Islam". His whereabout following his release was not known, and his wife said she "had not heard from him".[10]

Another convert, Shoaib Assadullah, was arrested in October 2010 "after allegedly giving a copy of a Bible to a friend". He was released in March 2011 and left Afghanistan.[11]

In 2012, a secular university teacher from Ghazni Province named Javeed wrote an article criticising the Taliban in English. The Taliban tried to seize him, but he and his wife Marina, a well-known Afghan television host, decided to flee to the Netherlands. In 2014 the article was translated to Pashto by the son-in-law of powerful warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, leading to an uproar on social media with many accusations of apostasy and death threats directed at Javeed, and a large public demonstration in Kabul calling for his execution.[12]

In late 2015, 21-year-old student and ex-Muslim atheist, Morid Aziz, was secretly recorded by his erstwhile girlfriend, Shogofa, criticising Islam and begged her to "forsake the darkness and embrace science". Shogofa, who had been radicalised whilst studying Sharia, played the recording at a mosque Friday prayer, following which came under considerable pressure to retract his remarks from his family and went into hiding shortly before a group of enraged men armed with Kalashnikovs showed up at his house. Twenty-three days later, he fled across several countries and ended up in the Netherlands, where he obtained permanent residency on 30 May 2017.[13]

Extra-constitutional

[edit]In August 1998 the Taliban insurgents slaughtered 8000 mostly Shia Hazara non-combatants in Mazar-i-Sharif, Afghanistan. The slaughter was called an act of revenge but also an act of takfir towards the Shia Hazara, after Mullah Niazi, the Taliban commander of the attack and newly installed governor, demanded loyalty, but also declared: "Hazaras are not Muslim, they are Shi'a. They are kofr [infidels]. The Hazaras killed our force here, and now we have to kill Hazaras. ... You either accept to be Muslims or leave Afghanistan."[14]

Algeria

[edit]Freedom of religion in Algeria is regulated by the Algerian Constitution, which declares Sunni Islam to be the state religion.[15]

According to Pew Research Center in 2010, 97.9% of Algerians were Muslim, 1.8% were unaffiliated, with the remaining 0.3% comprising adherents of other religions.[16]

By law, children follow the religion of their fathers, even if they are born abroad and are citizens of their (non-Muslim-majority) country of birth.[citation needed] The study of Islam is a requirement in both public and private schools for every Algerian child, irrespective of his or her religion.[17] Although the educational reform of 2006 eliminated "Islamic sciences" from the baccalaureate, Islamic studies are mandatory in public schools at the primary level and followed by Sharia studies at the secondary level. Concerns have been expressed that requests by non-Muslim religious students to opt out of these classes would result in discrimination.[15]

Muslim women cannot marry non-Muslim men (Algerian Family Code I.II.31),[18] and Muslim men may not marry women of non-monotheistic religious groups.[15] Prior to the 2005 amendments, family law stated that if it is established that either spouse is an "apostate" from Islam, the marriage will be declared null and void (Family Code I.III.32).[15] The term "apostate" was removed with the amendments, however those determined as such still cannot receive any inheritance (Family Code III.I.138).[15]

People without religious affiliation tend to be particularly numerous in Kabylie (a Kabyle-speaking area) where they are generally tolerated and sometimes supported.[15] Notably, Berber civil rights, human rights and secular activist and musician Lounès Matoub (assassinated in 1998) is widely seen as a hero among Kabyles, despite (or because of) his lack of religion.[19] In most other areas of the country, the non-religious tend to be more discreet, and often pretend to be pious Muslims to avoid violence and lynching.[15]

The "blasphemy" law is stringent and widely enforced. The non-religious are largely invisible in the public sphere, and although not specifically targeted through legislation, significant prejudice towards non-Muslim religions can be presumed to apply equally if not more so to non-believers.[15] The crime of "blasphemy" carries a maximum of five years in prison and the laws are interpreted widely. For example, several arrests have been made under the blasphemy laws in the last few years for failure to fast during Ramadan, even though this is not a requirement under Algerian law. Non-fasting persons (French: non-jeûneurs) repeatedly face harassment by the police and civil society.[15] Those who "renounce" Islam may be imprisoned, fined, or coerced to re-convert.[15]

Bangladesh

[edit]Bangladesh does not have a law against apostasy and its constitution ensures secularism and freedom of religion, but instances of persecution of apostates have been reported.

Feminist author Taslima Nasrin (who opposes sharia) suffered a number of physical and other attacks for her critical scrutiny of Islam,[20] before being driven into exile. In August 1994 she was brought up on "charges of making inflammatory statements", and faced criticism from Islamic fundamentalists. A few hundred thousand demonstrators called her "an apostate appointed by imperial forces to vilify Islam"; a member of a "militant faction threatened to set loose thousands of poisonous snakes in the capital unless she was executed."[21]

The radical Islamist group Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh, founded in 2010, created a hit list which included 83 outspoken atheist or secularist activists, including ex-Muslim bloggers and academics.[22] Dozens of atheist and secularist Bangladeshis on this list have been targeted for practicing "free speech" and disrespecting Islam, such as Humayun Azad, who was the target of a failed machete assassination attempt, and Avijit Roy, who was killed with meat cleavers; his wife Bonya Ahmed survived the attack.[23]

Since 2013, 8 of the 83 people on the hit list have been killed; 31 others have fled the country.[22] However the majority of the people criticized the killings and the government took strict measures and banned Islamist groups from politics.[24] On 14 June 2016 approximately 100,000 Bangladeshi Muslim clerics released a fatwa, ruling that the murder of "non-Muslims, minorities and secular activists ... [is] forbidden in Islam".

Belgium

[edit]

In the Western European country of Belgium, Muslims made up about 5–7% of the total population as of 2015.[25] Although legally anyone is free to change their religion, there is a social taboo on apostatising from Islam.[26][27] Moroccan-Belgian stand-up comedian Sam Touzani is a rare example of an outspoken ex-Muslim;[26] he was condemned by several fatwas and has received hundreds of death threats online, but persists in his criticism of Islam and Islamism.[28]

A Movement of Ex-Muslims of Belgium exists to support apostates from Islam, and to "fight Islamic indoctrination". As of 2014, it had a dozen members, who had to operate carefully and often anonymously.[29] Additionally, Belgian academics such as Maarten Boudry and Johan Leman have led efforts to try to normalise leaving Islam in Belgium.[30] On 16 November 2017, 25-year-old Hamza, shunned by his family (except for his supportive sister), came out as an ex-Muslim on television. He was seconded by philosopher and ex-Catholic Patrick Loobuyck, who argued that secularisation in the West gives Western Muslims such as Hamza the opportunity to embrace religious liberalism and even atheism.[31] In December 2018, De Morgen reported that Belgian ex-Muslims had been holding secret regular meetings in secure locations in Brussels since late 2017, supported by deMens.nu counselors.[9]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]During the Ottoman Turkish Muslim rule of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1463–1878), a large minority of the Southern Slavic-speaking inhabitants converted to Islam for various reasons, whilst others remained Roman Catholics (Croats) or Orthodox Christians (Serbs). These converts and their descendants were simply known as "Bosnian Muslims" or just "Muslims", until the term Bosniaks was adopted in 1993. In contemporary Balkans some Bosniaks are "Muslim" by name or cultural background, rather than conviction, profession or practice.[32] In a 1998 public opinion poll, just 78.3% of Bosniaks in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared themselves to be religious.[33]

The Ottomans punished apostasy from Islam with the death penalty until the Edict of Toleration 1844; subsequently, apostates could be imprisoned or deported instead.[34] When Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, this practice was abolished. The Austrian government held that any mature citizen was free to convert to another religion without having to fear any legal penalty, and issued a directive to its officials to keep their involvement in religious matters to a minimum. This clashed with the rigorous hostility to conversion exhibited by traditional Bosnian Muslims, who perceived it as a threat to the survival of Islam. During the four decades of Habsburg rule, several apostasy controversies occurred, most often involving young women with a low socio-economic status who sought to convert to Christianity.[35]

In August 1890, during the Austro-Hungarian rule in Bosnia and Herzegovina, a sixteen-year-old Bosnian girl called Uzeifa Delahmatović claimed to have voluntarily converted from Islam to Catholicism, the Habsburg state's official and majority religion. This stirred up controversy about whether she was forced, or whether a Muslim was even allowed to change their religion. Subsequent debates resulted in the Austrian Conversion Ordinance of 1891, which made religious conversion of subjects a matter of state. A strict procedure required the convert to be an adult and mentally healthy, and the conversion should be recognised by all parties involved; if not, the state would intervene and set up a commission for arbitration.[36]

In the 20th century, religion became highly politicised in Bosnia, and the basis for most citizens' national identity and political loyalty, leading to numerous conflicts culminating in the Bosnian War (1992–1995). The resulting violence and misery has caused a group of Bosnians to reject religion (and nationalism) altogether. This atheist community faces discrimination, and is frequently verbally attacked by religious leaders as "corrupt people without morals".[37]

Brunei

[edit]Brunei is the latest Muslim-majority country to enact a law that makes apostasy a crime punishable by death. In the Syariah (Sharia) Penal Code 2013, which came into full force in 2019, Section 112 of states that a Muslim who declares himself non-Muslim (an apostate) commits a crime punishable by death if proved by two witnesses or confession, or with imprisonment for a term not exceeding thirty years and whipping with up to 40 strokes if proved by other evidence.[38][39] After the required waiting period between notification of a law and its validity under Brunei's constitution, the new apostasy law came into effect in October 2015.[40][41]

Egypt

[edit]Legal situation

[edit]

Article 64 of the Egyptian Constitution enshrines "Freedom of Belief", which it states "is absolute". The article also states "the freedom of practicing religious rituals and establishing places of worship for the followers of revealed religions is a right organized by law."[43] Egypt also has no statutory ban on apostasy. It does have a blasphemy law (Article 98(f) of Egyptian Penal Code,[44] as amended by Law 147/2006), which has been used to prosecute and imprison Muslims (such as Bahaa El-Din El-Akkad in 2007)[45] who have converted to Christianity;[46] and a self-professed Muslim (Quranic scholar Nasr Abu Zayd in June 1995) has been found to be an apostate and his marriage declared null and void by the Egyptian Court of Cassation.[47]

Contemporary Egyptian jurisprudence prohibits apostasy from Islam, but has also remained silent about the death penalty.[48] Article 2 of the Constitution of Egypt enshrines sharia.[49] Both Court of Cassation and the Supreme Administrative Court of Egypt have ruled that "it is completely acceptable for non-Muslims to embrace Islam but by consensus Muslims are not allowed to embrace another religion or to become of no religion at all [in Egypt]."[48] In practice, Egypt has prosecuted apostasy from Islam under its blasphemy laws using the Hisbah doctrine;[50] hisbah complaints (accountability based on Islamic Sharia) are made by members of the public against other members about things like journal articles, a books, or a dance performances that the complainant believes "harmed the society's common interest, public morals, or decency".[51] "Hundreds of hisba cases have been registered against writers and activists, often using blasphemy or apostasy as a pretext".[52]

After the Hisbah apostasy complaint (a takfir) has been publicized, and non-state Islamic groups have sometimes taken the law into their own hands and executed apostates.[53] This was promoted by conservative scholar 'Adb al-Qadir 'Awdah, who preached that the killing of an apostate had become "a duty of individual Moslems", and that such a Muslim could plead impunity under Egyptian law, since the Egyptian Penal Code states that acts committed in good faith on the basis of a right laid down in the Shari'ah will not be punished.[Note 1]

A 2010 Pew Research Center poll showed that 84% of Egyptian Muslims believe those who leave Islam should be punished by death.[55]

Cases and incidents

[edit]In 1992, Islamist militants gunned down Farag Foda, an Egyptian secularist and sharia law opponent. A few weeks before his death he had been formally declared an apostate and foe of Islam by the ulama at Al Azhar.[50] During the trial of the murderers, Al-Azhar scholar Mohammed al-Ghazali testified that "when the state fails to punish apostates, somebody else has to do it".[53] Foda's eldest daughter defended her father, challenging his accusers to find "a single text in his writings against Islam".[56]

In 1994, Naguib Mahfouz, 82 years old at the time, was stabbed in the neck outside his home. Mahfouz was the only Arab ever to have been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature,[57] but was widely reviled by many revivalist preachers for the alleged blasphemy of his work Children of Gebelawi, which was banned by Egyptian religious authorities.[58] Several years before Mahfouz was stabbed, Omar Abdul-Rahman, "the blind sheikh" (he served time in a U.S. penitentiary for his involvement in the first World Trade Center bombing), "noted that had someone punished Mahfouz for his famous novel, Salman Rushdie would not have dared to publish Satanic Verses".[57] Preacher Abd al-Hamid Kishk accused Mahfouz of "violating Muslim sacred belief" and "supplanting monotheism with communism and scientific materialism".[59] Although he survived, Mahfouz produced fewer and fewer works because of the damage to his right arm.[60]

In 1993, a liberal Islamic theologian, Nasr Abu Zayd was denied promotion at Cairo University after a court decision of apostasy against him. Following this an Islamist lawyer filed a lawsuit before the Giza Lower Personal Status Court demanding the divorce of Abu Zayd from his wife, Dr. Ibtihal Younis, on the grounds that a Muslim woman cannot be married to an apostate – notwithstanding the fact his wife wished to remain married to him. The case went to the Cairo Appeals Court where his marriage was declared null and void in 1995.[61] After the verdict, the Egyptian Islamic Jihad organization (which had assassinated Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in 1981) declared Abu Zayd should be killed for abandoning his Muslim faith. Abu Zayd was given police protection, but felt he could not function under heavy guard, noting that one police guard referred to him as "the kafir".[62] On 23 July 1995, he and his wife flew to Europe, where they lived in exile but continued to teach.[61]

In 2001, feminist author, psychiatrist and self-professed Muslim, Nawal al-Saʿdawi, was charged with apostasy after she urged women to demand the right to multiple husbands just as men had the right to up to four wives under Islam.[63] She had earlier angered conservative Muslims by attacking unequal inheritance for women, female genital mutilation, and alleging the hajj pilgrimage had pagan origins. Using hisbah, a conservative lawuer called for the court to enforce a separation from her Muslim husband of 37 years.[64] Charges against her were dropped.[50]

In April 2006, after a court case in Egypt recognized the Baháʼí Faith, members of the clergy convinced the government to appeal the court decision. One member of parliament, Gamal Akl of the opposition Muslim Brotherhood, said the Baháʼís were infidels who should be killed on the grounds that they had changed their religion, although most living Baháʼí have not, in fact, ever been Muslim.[65]

In October 2006, Kareem Amer became the first Egyptian to be prosecuted for their online writings, including declaring himself an atheist. He was imprisoned until November 2010.[66]

In 2007 Mohammed Hegazy, a Muslim-born Egyptian who had converted to Christianity based on "readings and comparative studies in religions", sued the Egyptian court to change his religion from "Islam" to "Christianity" on his national identification card. His case caused considerable public uproar, with not only Muslim clerics, but his own father and wife's father calling for his death. Two lawyers he had hired or agreed to hire both quit his case, and two Christian human rights workers thought to be involved in his case were arrested. As of 2007, he and his wife were in hiding. In 2008, the judge trying his case ruled that according to sharia, Islam is the final and most complete religion and therefore Muslims already practice full freedom of religion and cannot convert to an older belief.[67][68][69] Hegazy kept trying to officially change his religion until he was arrested in 2013 for "spreading false rumours and incitement". He was released in 2016, after which he published a video on YouTube claiming he had reverted to Islam, and asked to be left alone.[70]

In May 2007, Bahaa El-Din El-Akkad, a former Egyptian Muslim and member of Tabligh and Daawa (an organization to spread Islam), was imprisoned for two years under the charge of "blasphemy against Islam" after converting to Christianity. He was freed in 2011.[46][71]

In February 2009, another case of a convert to Christianity (Maher Ahmad El-Mo'otahssem Bellah El-Gohary), came to court. El-Gohary's effort to officially convert to Christianity triggered state prosecutors charging him with apostasy and seeking a sentence of death.

"Our rights in Egypt, as Christians or converts, are less than the rights of animals", El-Gohary said. "We are deprived of social and civil rights, deprived of our inheritance and left to the fundamentalists to be killed. Nobody bothers to investigate or care about us." El-Gohary, 56, has been attacked in the street, spat at and knocked down in his effort to win the right to officially convert. He said he and his 14-year-old daughter continue to receive death threats by text message and phone call.[72]

Some commentators have reported a growing trend of abandoning religion following the Egyptian Revolution of 2011, reflected through emergence of support groups on social media, although openly declared apostates still face ostracism and danger of prosecution and vigilante violence.[73][74] A well-known example is the Internet activist Aliaa Magda Elmahdy (then-girlfriend of Kareem Amer), who protested the oppression of women's rights and sexuality in Islam by posting a nude photo of herself online.[75] In 2011, the Muslim woman Abeer allegedly converted to Christianity, and was given protection by the Church of Saint Menas in Imbaba. Hundreds of angry salafists beleaguered the church and demanded her return; during the resulting clashes, ten people were killed and hundreds were wounded.[70]

Eritrea

[edit]Muslims constitute approximately 36.5–37%[76][77] to 48–50%[78] of the Eritrean population; more than 99% of Eritrean Muslims are Sunnis.[76] Although there are no legal restrictions on leaving Sunni Islam, there are only three other officially recognised religions in Eritrea, all of them Christian: the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, the Eritrean Catholic Church (in full communion with the Roman Catholic Church) and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea.[79][80] Despite other religious groups applying for original recognition since 2002, the Eritrean government has failed to implement the relevant rights established in the constitution. It is illegal or unrecognised to identify as an atheist or as non-religious, and illegal to register an explicitly humanist, atheist, secularist or other non-religious NGO or other human rights organisation, or such groups are persecuted by authorities. Members of "unrecognised" religions are arrested, detained in oppressive conditions, and there have been reports that people have been tortured in order for them to recant their religious affiliation. Reports of the harassment and arrest of members of religious minority groups is widespread and frequent.[81] Open Doors reported that Muslims who become Christians in Muslim-majority areas are frequently rejected, mistreated or even disowned by their families. Additionally, the Orthodox Church considers itself the only true Christian denomination in the country and puts its ex-members who convert to a Protestant faith under pressure to return.[82]

India

[edit]According to the 2011 census, there were about 172 million Muslims living in India, accounting for approximately 14.2% of the total population.[83] According to a 2021 Pew research report, 12% of Indian Muslims' belief in God is of less certainty, where as 6% of Indian Muslims are not likely to believe in God.[84] In the early 21st century, an un-organised ex-Muslim movement started to emerge in India, typically amongst young (in their 20s and 30s) well-educated Muslim women and men in urban areas.[85] They are often troubled by religious teachings and practices (such as shunning of and intolerance and violence towards non-Muslims), doubting their veracity and morality, and started to question them.[85] Feeling that Islamic relatives and authorities failed to provide them with satisfactory answers, and with access to alternative interpretations of and information about Islam on the Internet, and the ability to communicate with each other through social media, these people resolved to apostatise.[85] According to Bhavya Dore, some ex-Muslims are disenchanted by the religious texts, while others are put off by hard-line clergy or religion in general.[86] According to Sultan Shahin, not only ex-Muslims but also rationalists live in much fear of their own Muslim community since mere utterance of disbelief may lead to charges of apostasy and community boycott.[86] According to P. Sandeep, while in most Islamic countries apostates face penal action including the death penalty in many cases, in India, being a secular democracy, even though apostasy is not a crime, those who leave Islam tend to face socio-economic ostracism and even violence from the hardliners among the Muslim community.[87] P. Sandeep says (some radical) Islamic clerics in India tend to use various types of bullying tactics to bully those who renounce religion or criticise its beliefs. Oftentimes these intimidation manoeuvres violate the fundamental human rights of individuals.[87] P. Sandeep says usually these pressure tactics include eviction, pressuring families to ex-communicate the apostatizing member; also forcing the spouse of the apostate to divorce, obstructing an apostates from contacting their own children, denying a share in inheritance, and obstructing marriages. P. Sandeep says that (some radical) Islamic clergy threaten families who refuse to follow fiats[clarification needed] with social ostracism.[87]

P. Sandeep says other manoeuvres to discourage apostasy and criticism of religion include accusing or filing with false cases. Filing of false cases is not limited within India but pursued even abroad.[87] If an apostate or critic does not concede despite these pressures, they can face threats, physical attacks or killing.[87] Because of the severity of such threats, most people are afraid of publicly criticizing or disowning Islam.[87] P. Sandeep's report says despite such risks, social media affords some margin of privacy since it allows use of pseudonyms, which has helped in reduction of risk of physical attacks to an extent.[87] But still, critics of Islam continue to face bullying and reporting and they cannot go around openly because of fear and risks to their lives.[87]

According to Arif Hussein Theruvath, while some critics express their concern whether right-wing politics is behind criticism of Islam, ex-Muslims themselves refute these claims.[88][86]

Shahin says thinking Muslims are getting exposed to a variety of ideas due to the internet, which is impacting Islam the same way advent of the printing press impacted Christianity.[86] Increasing popularity of social media apps like Clubhouse are helping redefining of the contours of debates surrounding Islam in states like Kerala.[88]

Indonesia

[edit]

The constitution provides for freedom of religion, accords "all persons shall be free to choose and to practice the religion of his/her choice".[89] But Indonesia has as a broad blasphemy law that protects all six recognised religions (Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism) (Article 156) and a Presidential Decree (1965) that permits prosecution of people who commit blasphemy.[90] The Decree prohibits every Indonesian from "intentionally conveying, endorsing or attempting to gain public support in the interpretation of a certain religion; or undertaking religious based activities that resemble the religious activities of the religion in question, where such interpretation and activities are in deviation of the basic teachings of the religion."[91] These laws have been used to arrest and convict atheist apostates in Indonesia, such as the case of 30-year-old Alexander Aan who declared himself to be an atheist, declared "God does not exist", and stopped praying and fasting as required by Islam. He received death threats from Islamic groups and in 2012 was arrested and sentenced to two and a half years in prison.[92][93]

Iran

[edit]Legal situation

[edit]Though nothing in the legal code of the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) mentions apostasy, and it is not "explicitly proscribed by the Iranian legal framework",[94] courts in the IRI have handed down the death penalty for apostasy in previous years, "based on their interpretation of Sharia’a law and fatwas (legal opinions or decrees issued by Islamic religious leaders)".[95]

Specifically, article 61 of the Constitution of the IRI states that "the functions of the Judiciary are to be performed by courts of justice formed in accordance with the criteria of Islam and vested with the authority to ... implement the penalties prescribed by God (hudũd-e Ilãhí)",[96] so that though a crime may not be "specifically mentioned in the criminal code", nonetheless the code "authorizes the enforcement" of "penalties prescribed by God", aka hudud[94] (hudud being punishments mandated and fixed by God according to Islamic law aka shariah). According to the Iran human Rights Documentation Center, "the differences in interpretations of Islamic law regarding apostasy, contribute to a lack of legal certainty for those living under Iranian laws."[94] In addition the crime of "swearing at the Prophet" (defined as making "utterances that are deemed derogatory towards Muhammad, other Shi'a holy figures, or other divine prophets")[94] is specifically criminalized in the Penal Code of the Islamic Republic as a capital offence.[94] [Note 2] While as of circa 2013 there has been an "absence of recent punishment" for apostasy, this "does not mean" that there have been "no execution of converts, within or outside the judicial system", because killing of apostates (such as Mehdi Dibaj and other Protestant pastors) sometimes takes place after the offenders have been released from the court system.[98][99]

Cases and incidents

[edit]As of 2014, individuals who have been "targeted and prosecuted" by the Iranian state for apostasy (and blasphemy/"Swearing at the Prophet") are "diverse" and include "Muslim-born converts to Christianity, Bahá'ís, Muslims who challenge the prevailing interpretation of Islam, and others who espouse unconventional religious beliefs"; some cases have had "clear political overtones", while others "seem to be primarily of a religious nature".[94] Executions for these crimes in Iran, however, has been "rare";[94] as of 2020, no one had been executed for apostasy since 1990.[95]

Converts

[edit]This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Were the 15 Christians executed? Were the proposed laws passed?. (July 2024) |

In 1990, Hossein Soodmand, who converted from Islam to Christianity when he was 13 years old, was executed by hanging for apostasy.[100]

According to US think tank Freedom House, since the 1990s the Islamic Republic of Iran has sometimes used death squads against converts, including major Protestant leaders.

Under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013), the regime has engaged in a systematic campaign to track down and reconvert or kill those who have changed their religion from Islam.[6] (Christian sources claim between 250,000 and 500,000 Muslims have converted to Christianity in Iran from 1960 to 2010.)[101]

Fifteen ex-Muslim Christians[102] were incarcerated on 15 May 2008 under charges of apostasy. They may face the death penalty if convicted. A new penal code is being proposed[timeframe?] in Iran that would require the death penalty in cases of apostasy on the Internet.[103]

Non-converts

[edit]At least two Iranians – Hashem Aghajari and Hassan Youssefi Eshkevari – have been arrested and charged with apostasy in the Islamic Republic (though not executed), not for self-professed conversion to another faith, but for statements and/or activities deemed by courts of the Islamic Republic to be in violation of Islam, and that appear to outsiders to be Islamic reformist political expression.[104] Hashem Aghajari was found guilty of apostasy for a speech urging Iranians to "not blindly follow" Islamic clerics;[105] Hassan Youssefi Eshkevari was charged with apostasy for attending the 'Iran After the Elections' Conference in Berlin Germany which was disrupted by anti-regime demonstrators.[106]

1988 mass executions of Iranian political prisoners

[edit]In 1988, thousands of political prisoners were secretly executed in the IRI, outside of the workings of the government judicial system, but by order of the Ayatollah Khomeini, Supreme Leader of the IRI.[107] (Though the killings were carried out in secret by "Special Commissions" and the government denies their having taken place, human rights groups have been able to gather information from interviews with relatives,[108] survivors,[109] and a high level dissident, namely Hussein-Ali Montazeri).[110]

Most of the estimated almost 4,500[108] to more than 30,000[111] victims were members of People's Mojahedin Organization of Iran, executed as moharebs (those who "wage war against Allah"); but many were secular leftists.[Note 3] It is thought these (leftist) prisoners were executed for apostasy because they were asked questions – "Do you believe in Allah?", "Will you denounce your former beliefs before the cameras?", "Do you fast during Ramadan?", "When you were growing up, did your father pray, fast, and read the Holy Qur'an?" – consistent with determining whether they were apostates as defined by Islamic doctrine, and because they were executed if their answers indicated that they were.[112] (The assumption was that they came from Muslim families but, being secular leftists, had abandoned Islam.)[107]

Baháʼí

[edit]Baháʼís are Iran's largest religious minority, and Iran is the nation of origin of that Faith. Officially, Baháʼís are not a religion but a "political faction" and a security threat in the IRI, but originally Baháʼís were accused of apostasy by the Shi'a clergy. Baháʼí representatives have also alleged that "the best proof" that they are being persecuted for their faith, not for anti-Iranian activity, "is the fact that, time and again, Baha'is have been offered their freedom if they recant their Baha'i beliefs and convert to Islam"[113] – because of their adherence to religious revelations by another prophet after those of Muhammad – and these allegations led to mob attacks, public executions and torture of early Baháʼís, including its founder the Báb.[114] More recently, Musa Talibi was arrested in 1994, and Dhabihu'llah Mahrami was arrested in 1995, then sentenced to death on charges of apostasy.[115]

Sufi

[edit]In August 2018, more than 200 members of a Dervish Sufi order (Nemattolah Gonabadi) were sentenced to "prison terms ranging from four months to 26 years, flogging, internal exile, travel bans". The group is not illegal in Iran and the punishments were for demonstrating to protect the residence of their spiritual leader, but according to rights groups the judges reportedly "insulted the accused and focused their questions on their faith as opposed to any recognizable crime".[116] In July 2013 eleven Sufi activists were given sentences of from one to ten-and-a-half years in prison, to be followed by periods of internal exile, for among other charges "establishing and membership in a deviant group".[117]

Atheists

[edit]In July 2017, an activist group that spread atheistic articles and books Iranian universities, published a video on YouTube titled "Why we must deny the existence of God", featuring famous atheist thinkers Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Christopher Hitchens and Daniel Dennett. An hour before the group would meet to discuss the production of a new video, their office was raided by the police. Group member Keyvan (32), raised as a Sunni Muslim but confusingly educated in a Shia school, long had doubts about religion, and became an apostate after reading atheist literature. He and his wife had to flee after the police raid, and flew to the Netherlands three days later.[118]

Iraq

[edit]

Although the Constitution of Iraq recognises Islam as the official religion and states that no law may be enacted that contradicts the established provisions of Islam, it also guarantees freedom of thought, conscience, and religious belief and practice. While the Government generally endorses these rights, unsettled conditions have prevented effective governance in parts of the country, and the Government's ability to protect religious freedoms has been handicapped by insurgency, terrorism, and sectarian violence. Since 2003, when the government of Saddam Hussein fell, the Iraqi government has generally not engaged in state-sponsored persecution of any religious group, calling instead for tolerance and acceptance of all religious minorities.

In October 2013, 15-year-old Ahmad Sherwan from Erbil said he no longer believed in God and was proud to be an atheist to his father, who had the police arrest him. He was imprisoned for 13 days and tortured several times, before being released on bail; he faced life imprisonment for disbelief in God. Sherwan tried to contact the media for seven months, but all refused to run his story until the private newspaper Awene published it in May 2014. It went viral, and human rights activists came to his aid.[119]

The 2014 uprising of the Islamic State (IS or ISIS) has led to violations of religious freedom in certain parts of Iraq.[120] ISIS follows an extreme anti-Western interpretation of Islam, promotes religious violence, and regards those who do not agree with its interpretations as infidels or apostates.[121]

Islam has given me nothing, no respect, no rights as a woman.

In the 2010s, an increasing number of Iraqis, especially young people in the capital city of Baghdad and the Kurdistan Region, were leaving Islam for a variety of reasons. Some cite the lack of women's rights in Islam, others the political climate, which is dominated by conflicts between Shia Muslim parties who seek to expand their power more than they try to improve citizens' living conditions. Many young ex-Muslims sought refuge in the Iraqi Communist Party, and advocated for secularism from within its ranks. The sale of books on atheism by authors such as Abdullah al-Qasemi and Richard Dawkins has risen in Baghdad. In Iraqi Kurdistan, a 2011 AK-News survey asking whether respondents believed God existed, resulted in 67% replying 'yes', 21% 'probably', 4% 'probably not', 7% 'no' and 1% had no answer. The subsequent harsh battle against Islamic State and its literalist implementation of Sharia caused numerous youths to dissociate themselves from Islam altogether, either by adopting Zoroastrianism or secretly embracing atheism.[122]

When Sadr al-Din learned about natural selection in school, he began questioning the relationship between Islam and science, studying the history of Islam, and asking people's opinions on both topics. At the age of 20, he changed his first name to Daniel, after atheist philosopher Daniel Dennett. He came into conflict with his family, who threatened him with death, and after his father found books in his room denying the existence of God and miracles, he tried to shoot his son. Daniel fled Iraq, and obtained asylum in the Netherlands.[118]

Jordan

[edit]Jordan does not explicitly ban apostasy in its penal code; however, it permits any Jordanian to charge another with apostasy and its Islamic courts to consider conversion trials.[123] If an Islamic court convicts a person of apostasy, it has the power to sentence a prison term, annul that person's marriage, seize property, and disqualify him or her from inheritance rights. The Jordanian poet Islam Samhan was accused of apostasy for poems he wrote in 2008, and sentenced to a prison term in 2009.[124][125]

Kosovo

[edit]Crypto-Catholics

[edit]Kosovo was conquered by the Ottoman Empire along with the other remnants of the Serbian Empire in the period following the Battle of Kosovo (1389). Although the Ottomans did not force the Catholic and Orthodox Christian population to convert to Islam, there was strong social pressure (such as not having to pay the jizya) as well as political expediency to do so, which ethnic Albanians did in far greater numbers (including the entire nobility) than Serbs, Greeks and others in the region.[126] Many Albanian Catholics converted to Islam in the 17th and 18th centuries, despite attempts by Roman Catholic clergy to stop them, including a strict condemnation of conversion – especially for opportunistic reasons such as jizya evasion – during the Concilium Albanicum, a meeting of Albanian bishops in 1703. Whilst many of these converts stayed crypto-Catholics to a certain extent, often helped by pragmatic lower clerics, the higher Catholic clergy ordered them to be denied the sacraments for their heresy.[34] Efforts to convert the laraman community of Letnica back to Catholicism began in 1837, but the effort was violently suppressed; the local Ottoman governor put laramans in jail.[127] After the Ottoman Empire abolished the death penalty for apostasy from Islam by the Edict of Toleration 1844, several groups of crypto-Catholics in Prizren, Peja and Gjakova were recognised as Catholics by the Ottoman Grand Vizier in 1845. When the laramans of Letnica asked the district governor and judge in Gjilan to recognise them as Catholics, they were refused however, and subsequently imprisoned, and then deported to Anatolia,[128] from where they returned in November 1848 following diplomatic intervention.[129] In 1856, a further Tanzimat reform, the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856, improved the situation, and no further serious abuse was reported.[130] The bulk of conversion of laramans, almost exclusively newly-borns, took place between 1872 and 1924.[131]

Kuwait

[edit]The law in Kuwait does not explicitly prohibit apostasy.[132][133][134] Kuwait does not have a law that criminalizes apostasy.[132][135][133][134] In practice, the family law for Muslims can prosecute Muslims for apostasy because the family court has the power to annul that person's marriage, property, and inheritance rights.[136][137] In 1996, the Kuwaiti citizen Hussein Qambar Ali was prosecuted in a Shia Muslim family court on charges of apostasy after he converted from Islam to Christianity.[133][138][139]

Libya

[edit]Atheism is prohibited in Libya and can come with a death penalty, if one is charged as an atheist.[141]

In June 2013, Libya's General National Council assembly (GNC) voted to make Islamic Sharia law the basis for all legislation and for all state institutions, a decision having an impact in banking, criminal, and financial law.[142] In February 2016, Libya's General National Council assembly (GNC) released adecree No.20 Changing on provisions of the Libyan Penal Code.[141]

Malaysia

[edit]Legal situation

[edit]Malaysia does not have a national law that criminalizes apostasy and its Article 11 grants freedom of religion to its diverse population of different religions.[143] However, Malaysia's constitution grants its states (Negeri) the power to create and enforce laws relating to Islamic matters and Muslim community.[143] State laws in Kelantan and Terengganu make apostasy in Islam a crime punishable with death, while state laws of Perak, Malacca, Sabah, and Pahang declare apostasy by Muslims as a crime punishable with jail terms. In these states, apostasy is defined as conversion from Islam to another faith, but converting to Islam is not a crime. The central government has not attempted to nullify these state laws, but stated that any death sentence for apostasy would require review by national courts.[144][145] Ex-Muslims can be fined, jailed or sent for counselling.[146]

National laws of Malaysia require Muslim apostates who seek to convert from Islam to another religion to first obtain approval from a sharia court. The procedure demands that anyone born to a Muslim parent, or who previously converted to Islam, must declare himself apostate of Islam before a Sharia court if he or she wants to convert. The Sharia courts have the power to impose penalties such as jail, caning and enforced "rehabilitation" on apostates – which is the typical practice. In the states of Perak, Malacca, Sabah, and Pahang, apostates of Islam face jail term; in Pahang, caning; others, confinement with rehabilitation process.[144]

The state laws of Malaysia allow apostates of other religion to become Muslim without any equivalent review or process. The state laws of Perak, Kedah, Negeri Sembilan, Sarawak, and Malacca allow one parent to convert children to Islam even if the other parent does not consent to his or her child's conversion to Islam.[144]

In a highly public case, the Malaysian Federal Court did not allow Lina Joy to change her religion status in her I/C in a 2–1 decision.[citation needed]

Cases and incidents

[edit]In August 2017, a picture from a gathering of the Atheist Republic Consulate of Kuala Lumpur was posted on Atheist Republic's Facebook page. Deputy Minister of Islamic Affairs Asyraf Wajdi Dusuki ordered an inquiry into whether anyone in the picture had committed apostasy or had 'spread atheism' to any Muslims present, both of which are illegal in Malaysia.[147][146] The next day, Minister in the Prime Minister's Department Shahidan Kassim stated atheists should be "hunted down", as there was no place for groups like this under the Federal Constitution.[148][149] Atheist Republic (AR) members present at the gathering reportedly received death threats on social media.[147][146] Canada-based AR leader Armin Navabi asked: "How is this group harming anyone?", warning that such actions by the government damaged Malaysia's reputation as a "moderate" Muslim-majority (60%) country.[147] The uploads sparked violent protests from some Malaysians calling Navabi an 'apostate' and threatening to behead him.[150] A Kuala Lumpur AR Consulate admin told BBC OS that such meetings are just socialising events for "people who are legally Muslim, and atheists, and people from other religions as well".[149] In November 2017, it was reported that Facebook had rejected a joint government and Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission demand to shut down Atheist Republic's page and similar atheist pages, because the pages did not violate any of the company's community standards.[151]

Maldives

[edit]

The Constitution of the Maldives designates Islam as the official state religion, and the government and many citizens at all levels interpret this provision to impose a requirement that all citizens must be Muslims. The Constitution states the president must be a Sunni Muslim. There is no freedom of religion or belief.[153] This situation leads to institutionally sanctioned religious oppression against non-Muslims and ex-Muslims who currently reside in the country.

On 27 April 2014, the Maldives ratified a new regulation that revived the death penalty (abolished in 1953, when the last execution took place) for a number of hudud offences, including apostasy for persons from the age of 7 and older. The new regulation was strongly criticised by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the EU's High Representative, pointing out that they violated the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which the Maldives have ratified, that ban the execution of anyone for offences committed before the age of 18.[154][155]

Cases and incidents

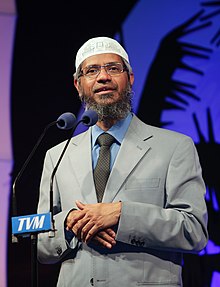

[edit]During a question-and-answer session at one of Indian Muslim orator Zakir Naik's lectures 29 May 2010 on the Maldives, 37-year-old Maldivian citizen Mohamed Nazim stated that he was struggling to believe in any religion, and did not consider himself to be a Muslim. He further asked what his verdict would be under Islam and in the Maldives.[152][156] Zakir responded that he considers the punishment for apostasy not necessarily to mean death, since Muhammed was reported in the Hadith scriptures to have shown clemency towards apostates on some occasions, but added that "If the person who becomes a non-Muslim propagates his faith and speaks against Islam [where] there is Islamic rule, then the person is to be put to death."[152] Mohamed Nazim was subsequently reported to have been arrested and put in protective custody by the Maldivian Police. He later publicly reverted to Islam in custody after receiving two days of counseling by two Islamic scholars, but was held awaiting possible charges.[157][158][159]

On 14 July 2010, Maldivian news site Minivan News[160] reported that 25-year-old air traffic controller Ismail Mohamed Didi had sent two e-mails, dated 25 June, to an international human rights organisation, declaring that he was an atheist ex-Muslim and that he desired help with his asylum application (directed to the United Kingdom). This came after he had "foolishly admitted my stance on religion" to his colleagues at work two years earlier, word of which had "spread like wildfire", and led to increased repression from colleagues, family, and even his closest friends shunning him, and anonymous death threats over the telephone. The same day that the report was posted, Didi was found hanged at his workplace in the aircraft control tower at Malé International Airport in an apparent suicide.[161]

Mauritania

[edit]

Article 306 of the criminal code of Mauritania declares apostasy in Islam as illegal and provides a death sentence for the crime of leaving Islam.[162] Its law provides a provision where the guilty is given the opportunity to repent and return to Islam within three days. Failure to do so leads to a death sentence, dissolution of family rights and property confiscation by the government. The Mauritanian law requires that an apostate who has repented should be placed in custody and jailed for a period for the crime.[162] Article 306 reads:

All Muslims guilty of apostasy, either spoken or by overt action will be asked to repent during a period of three days. If he does not repent during this period, he is condemned to death as an apostate, and his belongings confiscated by the State Treasury.[163]

Cases and incidents

[edit]In 2014, Jemal Oumar, a Mauritanian journalist, was arrested for apostasy, after he posted a critique of Mohammad online.[164] While local law enforcement agencies held him in prison for trial, local media announced offers by local Muslims of cash reward to anyone who would kill Jemal Oumar.

In a separate case, Mohamed Mkhaitir, a Mauritanian engineer, was arrested with the accusation of apostasy and blasphemy in 2014 as well, for publishing an essay on the racist caste system in Mauritanian society with criticism of Islamic history and a claim that Mohammad discriminated in his treatment of people from different tribes and races.[165] Supported by pressure from human rights activists and international diplomats, Mkhaitir's case was reviewed several times, amid public civilian protests calling for him to be killed.[166] On 8 November 2017 the Court of Appeals decided to convert his death sentence into a two-year jail term, which he had already served, so he was expected to be released soon.[167] However, by May 2018 he still had not been released according to human rights groups.[168] In July 2019, he was finally released and eventually able to start a new life in exile in Bordeaux, France.[169]

Morocco

[edit]The penal code of Morocco does not impose the death penalty for apostasy. However, Islam is the official state religion of Morocco under its constitution. Article 41 of the Moroccan constitution gives fatwa powers (habilitée, religious decree legislation) to the Supreme Council of Religious Scholars, which issued a religious decree, or fatwa, in April 2013 that Moroccan Muslims who leave Islam must be sentenced to death.[170][171] However, Mahjoub El Hiba, a senior Moroccan government official, denied that the fatwa was in any way legally binding.[172] This decree was retracted by the Moroccan High Religious Committee in February 2017 in a document titled "The Way of the Scholars".[173] It instead states that apostasy is a political stance rather than a religious issue, equatable to "high treason".

Cases and incidents

[edit]When he was 14, Imad Iddine Habib came out as an atheist to his family, who expelled him. Habib stayed with friends, got a degree in Islamic studies and founded the Council of Ex-Muslims of Morocco in 2013. Secret services started investigating him after a public speech criticising Islam, and Habib fled to England, after which he was sentenced to seven years in prison in absentia.[174]

Netherlands

[edit]In the Netherlands, a country in Western Europe, Muslims made up about 4.9% of the total population as of 2015; the rest of its inhabitants were either non-religious (50.1%), Christian (39.2%) or adherents of various other religions (5.7%).[175] Although the freedom of expression, thought and religion is guaranteed by law in the Netherlands, there is doubt concerning the reality of this individual freedom within the small orthodox Christian minorities and within Muslim communities. The social and cultural pressure for those raised in a conservative religious family not to change or 'lose' religion can be high. This lack of 'horizontal' freedom (the freedom in relation to family, friends and neighborhood) remains a concern. Ex-Muslims often keep their views hidden from family, friends and the wider community.[176]

Ayaan Hirsi Ali deconverted from Islam after seeing the September 11 attacks being justified by Al Qaeda's leader Osama bin Laden with verses from the Quran that she verified personally, and subsequently reading Herman Philipse's Atheïstisch manifest ("Atheist Manifesto"). She soon became a prominent critic of Islam amidst an increasing number of death threats from Islamists and thus a need for security.[177] She was elected to Parliament in 2003 for the VVD, and co-producing Theo van Gogh's short film Submission (broadcast on 29 August 2004), which criticised the treatment of women in Islamic society.[178] This led to even more death threats, and Van Gogh was assassinated on 2 November 2004 by jihadist terrorist Hofstad Network leader Mohammed Bouyeri.[178] He threatened Hirsi Ali and other nonbelievers by writing that her "apostasy had turned her away from the truth", "only death can separate truth from lies", and that she would "certainly perish".[179] Gone into hiding and heavily protected, she received a string of international awards, including one of Time's 100 most influential people of the world, for her efforts at highlighting Islam's violation of human rights, especially women's rights, before moving to the United States in 2006 following a Dutch political crisis over her citizenship.[177]

Ehsan Jami, co-founder of the Central Committee for Ex-Muslims in the Netherlands in 2007, has received several death threats, and due to the number of threats its members received, the committee was dismantled in 2008.[180] To fill this lacuna, the Dutch Humanist Association (HV) launched the Platform of New Freethinkers in 2015.[181] There is a Dutch-speaking group for Muslim apostates born and/or raised in the Netherlands, and an English-speaking one for ex-Muslims who recently arrived in the Netherlands as refugees. The latter fled their country because they were discriminated against or confronted with threats, violence or persecution because of their humanist or atheist life-stance.[176] The HV and Humanistische Omroep cooperated under the direction of Dorothée Forma to produce two documentaries on both groups: Among Nonbelievers (2015) and Non-believers: Freethinkers on the Run (2016).[182]

Nigeria

[edit]

In Nigeria, there is no federal law that explicitly makes apostasy a crime. The Federal Constitution protects freedom of religion and allows religious conversion. Section 10 of the constitution states, "The Government of the Federation of a State shall not adopt any religion as State Religion."[184]

However, 12 Muslim-majority states in northern Nigeria have laws invoking Sharia, which have been used to persecute Muslim apostates, particularly Muslims who have converted to Christianity.[185][186] Although the states of Nigeria have a degree of autonomy to adopt their own laws, the first paragraph of the Federal Constitution stipulates that any law inconsistent with the provisions of the constitution shall be void.[187] The Sharia penal code does contradict the Constitution, yet the federal government has not made a move to restore this breach of the constitutional order, letting the northern Muslim-dominated states have their way and not protecting the constitutional rights of citizens violated by Sharia.[187]

Governor Ahmad Sani Yerima of Zamfara State, the first Nigerian Muslim-majority state to introduce Sharia in 2000, stated that because capital punishment for apostasy was unconstitutional, citizens themselves should do the killing, effectively undermining the rule of law:[187]

If you change your religion from Islam, the penalty is death. We know it. And we didn't put it in our penal code because it is against the constitutional provision. It is the law of Allah, which now is a culture for the entire society. So if a Muslim changes his faith or religion, it is the duty of the society or family to administer that part of the justice to him.[187]

Sani further added that whoever opposed "the divine rules and regulations ... is not a Muslim",[187] confirmed by Secretary-General of the Nigerian Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs Lateef Adegbite, who was quoted as saying:

Once you reject sharia, you reject Islam. So, any Muslim that protests the application of sharia is virtually declaring himself non-Muslim.[187]

In December 2005, Nigerian pastor Zacheous Habu Bu Ngwenche was attacked for allegedly hiding a convert.[6]

Oman

[edit]Oman does not have an apostasy law. However, under Law 32 of 1997 on Personal Status for Muslims, an apostate's marriage is considered annulled and inheritance rights denied when the individual commits apostasy.[188] The Basic Law of Oman, since its enactment in 1995, declares Oman to be an Islamic state and Sharia as the final word and source of all legislation. Omani jurists state that this deference to Sharia, and alternatively the blasphemy law under Article 209 of Omani law, allows the state to pursue death penalty against Muslim apostates, if it wants to.[188][189]

Palestine

[edit]The State of Palestine does not have a constitution; however, the Basic Law provides for religious freedom. The Basic Law was approved in 2002 by the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC) and signed by then-President Yasir Arafat. The Basic Law states that Islam is the official religion, but also calls for respect and sanctity for other "heavenly" religions (such as Judaism and Christianity) and that the principles of Shari'a (Islamic law) shall be the main source of legislation.[190]

The Palestinian Authority (PA) requires Palestinians to declare their religious affiliation on identification papers. Either Islamic or Christian ecclesiastical courts handle legal matters relating to personal status. Inheritance, marriage, and divorce are handled by such courts, which exist for Muslim and Christians.[190]

Citizens living in the West Bank found to be guilty of 'defaming religion' under the old Jordanian law, run the risk of years of imprisonment, up to for life. This happened to 26-year-old blogger Waleed Al-Husseini in October 2010, who was arrested and charged with defaming religion after openly declaring himself an atheist and criticising religion online.[190] He was detained for ten months. After being released, he eventually fled to France, as the PA continued to harass him, and citizens called for him to be lynched.[191] He later found out he was sentenced to seven-and-a-half years in prison in absentia.

Pakistan

[edit]Inheritance and property rights for apostates were prohibited by Pakistan in 1963.[192] In 1991, Tahir Iqbal, who had converted to Christianity from Islam, was arrested on charges of desecrating a copy of the Qur'an and making statements against Muhammad. While awaiting trial, he was denied bail on the presumption by a Sessions Court and the appeals Division of the Lahore High Court that conversion from Islam was a "cognizable offense". This decision was upheld by the High Court. The judge hearing the case, Saban Mohyuddin, rejected the idea that Iqbal should be sentenced to death for conversion, saying that Iqbal could only be sentenced if it could be proven he had committed blasphemy. The case was then transferred away from Mohyuddin.[193]

While there was no specific formal law prohibiting apostasy,[192] the laws against apostasy have been effectuated through Pakistan's blasphemy laws.[192] Under Article 295 of its penal code, any Pakistani Muslim who feels his or her religious feelings have been hurt, directly or indirectly, for any reason or any action of another Pakistani citizen can accuse blasphemy and open a criminal case against anyone.[194] AbdelFatteh Amor has observed that the Pakistani judiciary has tended to hold apostasy to be an offence, although Pakistanis have claimed otherwise.[195] The UN expressed concern in 2002 that Pakistan was still issuing death sentences for apostasy.[196]

The Apostasy Act 2006 was drafted and tabled before the National Assembly on 9 May 2007. The Bill provided an apostate with three days to repent or face execution. Although this Bill has not officially become law yet,[timeframe?] it was not opposed by the government which sent it to the parliamentary committee for consideration.[197] The principle in Pakistani criminal law is that a lacuna in the statute law is to be filled with Islamic law. In 2006 this had led Martin Lau to speculate that apostasy had already become a criminal offence in Pakistan.[198]

In 2010 the Federal Shariat Court declared that apostasy is an offence[199] covered by hudood under the terms of Article 203DD of the Constitution.[200][201] The Federal Shariat Court has exclusive jurisdiction over hudood matters and no court or legislation can interfere in its jurisdiction or overturn its decisions.[201] Even though apostasy is not covered in statutory law, the Court ruled that it had jurisdiction over all hudood matters regardless of whether there is an enacted law on them or not.[202]

Qatar

[edit]Apostasy in Islam is a crime in Qatar.[203] Its Law 11 of 2004 specifies traditional Sharia prosecution and punishment for apostasy, considering it a hudud crime punishable by death.[204]

Proselytizing of Muslims to convert to another religion is also a crime in Qatar under Article 257 of its law,[204] punishable with prison term. According to its law passed in 2004, if proselytizing is done in Qatar, for any religion other than Islam, the sentence is imprisonment of up to five years. Anyone who travels to and enters Qatar with written or recorded materials or items that support or promote conversion of Muslims to apostasy are to be imprisoned for up two years.[205]

Casual discussion or "sharing one's faith" with any Muslim resident in Qatar has been deemed a violation of Qatari law, leading to deportation or prison time.[206] There is no law against proselytizing non-Muslims to join Islam.

Saudi Arabia

[edit]

Saudi Arabia has no penal code, and defaults its law entirely to Sharia and its implementation to religious courts. The case law in Saudi Arabia, and consensus of its jurists, is that Islamic law imposes the death penalty on apostates.[208]

Apostasy law is actively enforced in Saudi Arabia. For example, Saudi authorities charged Hamza Kashgari, a Saudi writer, in 2012 with apostasy based on comments he made on Twitter. He fled to Malaysia, where he was arrested and then extradited on request by Saudi Arabia to face charges.[209] Kashgari repented, upon which the courts ordered that he be placed in protective custody. Similarly, two Saudi Sunni Muslim citizens were arrested and charged with apostasy for adopting the Ahmadiyya.[210] As of May 2014, the two accused of apostasy had served two years in prison awaiting trial.[211]

In 2012, the US Department of State alleged that Saudi Arabia's school textbooks included chapters which justified the social exclusion and killing of apostates.[212]

In 2015, Ahmad Al Shamri was sentenced to death for apostasy.[213]

In January 2019, 18-year-old Rahaf Mohammed fled Saudi Arabia after having renounced Islam and being abused by her family. On her way to Australia, she was held by Thai authorities in Bangkok while her father tried to take her back, but Rahaf managed to use social media to attract significant attention to her case.[214] After diplomatic intervention, she was eventually granted asylum in Canada, where she arrived and settled soon after.[215]

Somalia

[edit]Apostasy is a crime in Somalia.[203] Articles 3(1) and 4(1) of Somalia's constitution declare that religious law of Sharia is the nation's highest law. The prescribed punishment for apostasy is death.[216][217]

There have been numerous reports of executions of people for apostasy, particularly Muslims who have converted to Christianity. However, the reported executions have been by extra-state Islamist groups and local mobs, rather than after the accused has been tried under a Somali court of law.[218][219]

Sri Lanka

[edit]In Sri Lanka, 9.7% of the population is Muslim. Due to the social taboo on leaving Islam, the Council of Ex-Muslims of Sri Lanka (CEMSL) was founded in secret in 2016. Members of the organisation hold meetings in hiding. In June 2019, Rishvin Ismath decided to come forward as spokesperson for the Council in order to denounce government-approved and distributed textbooks for Muslim students which stated that apostates from Islam should be killed. Ismath subsequently received several death threats.[220]

Sudan

[edit]In Sudan, apostasy was punishable with the death penalty until July 2020.[221] Article 126.2 of the Penal Code of Sudan (1991) read,

Whoever is guilty of apostasy is invited to repent over a period to be determined by the tribunal. If he persists in his apostasy and was not recently converted to Islam, he will be put to death.[163]

Some notable cases of apostasy in Sudan included: Mahmoud Mohammed Taha, a Sudanese religious thinker, leader, and trained engineer, who was executed for "sedition and apostasy" in 1985 at the age of 76, as thousands of demonstrators protested against his execution,[222][223] by the regime of Gaafar Nimeiry.[224][225] Meriam Ibrahim, a 27-year-old Christian Sudanese woman, was sentenced to death for apostasy in May 2014, but allowed to leave the country in July after an international outcry.[226] Twenty-five Muslim men from the Hausa minority ethnicity were arrested at gunpoint in December 2015 and imprisoned for several weeks for "rejecting the prophet Muhammad's teaching" – charges punishable by death – because they took the Quran as the sole source for Islam.[227] The charges were condemned by the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF part of the US government),[228] the African Centre for Justice and Peace Studies and the Sudanese Human Rights Initiative.[227] The arrested adults were released on bail on 14 December 2015, in what lawyers for the accused believed to be "an attempt to deflect international criticism of the case".[227] On 3 March 2016 the Sudanese Ministry of Justice withdrew the case.[229]

Sudanese ex-Muslim and human rights activist Nahla Mahmoud estimated that during the years 2010, 2011 and 2012, there were between 120 and 170 Sudanese citizens who had been convicted for apostasy, most of whom repented to avoid a death sentence.[230]

In July 2020, Justice Minister Nasredeen Abdulbari announced that the punishment for apostasy had been scrapped a few days earlier, as the declaration that someone was an apostate was "a threat to the security and safety of society". The move was part of a wider scrapping of "all the laws violating the human rights in Sudan" during the 2019–2021 Sudanese transition to democracy.[221]

Tunisia

[edit]Following the 2010–11 Tunisian Revolution, a Constituent Assembly worked for 2.5 years to written a new Constitution, approved in January 2014, contained a provision in Article 6 granting freedom of conscience.[231][232] It also stipulates that "[a]ccusations of apostasy and incitement to violence are prohibited".[231] With it, Tunisia became the first Arab-majority country to protect its citizens from prosecution for renouncing Islam.[233] Critics have pointed out alleged flaws of this formulation, namely that it violates the freedom of expression.[231]

The highest profile cases of apostasy in Tunisia were of the two atheist ex-Muslims Ghazi Beji and Jabeur Mejri, sentenced to 7.5 years in prison on 28 March 2012. They were prosecuted for expressing their views on Islam, the Quran and Muhammad on Facebook, blogs and in online books, which allegedly "violated public order and morality". Mejri wrote a treatise in English on Muhammad's supposedly violent and sexually immoral behaviour.[234] When Mejri was arrested by police, he confessed under torture[235][234] that his friend Beji had also authored an antireligious book, The Illusion of Islam, in Arabic. Upon learning he, too, was sought by the police, Beji fled the country and reached Greece;[234] he obtained political asylum in France on 12 June 2013.[236] Mejri was pardoned by president Moncef Marzouki and left prison on 4 March 2014[237] after several human rights groups campaigned for his release under the slogan "Free Jabeur".[235][238] When Mejri wanted to accept Sweden's invitation to move there, he was again imprisoned for several months, however, after being accused of embezzling money from his former job by his ex-colleagues[238] (who started bullying him as soon as they found out he was an atheist),[235][234] a rumour spread by his former friend Beji[235] (who felt betrayed by Mejri because he had outed him as an atheist).[234]

Turkey

[edit]Although claiming to be a secular country and legally not enforcing any punishments for apostasy from Islam in Turkey, there are several formal and informal mechanisms in place that make it hard for citizens to be registered as non-Muslim.

Article 216 of the penal code outlaws insulting religious belief, often used as a de facto blasphemy law obstructing citizens from expressing irreligious views, or views critical of religions. A well-known example is that of pianist Fazıl Say in 2012, who was charged with insulting religion for publicly mocking Islamic prayer rituals (though the conviction was reversed by the Turkish Supreme Court, which determined Say's views were a protected expression of his freedom of conscience). Irreligious Turks are also often discriminated against in the workplace, since people are generally assumed to be Muslim by birth, and terms such as 'atheist' or 'nonbeliever' are frequently used insults in the public sphere.[239]

In 2014, the Turkish atheist association Ateizm Derneği was founded for non-religious citizens, many of whom having left Islam. The association won the International League of non-religious and atheists's Sapio Award 2017 for being the first officially recognised organisation in the Middle East defending the rights of atheists.[240]

An early April 2018 report of the Turkish Ministry of Education, titled "The Youth is Sliding to Deism", observed that an increasing number of pupils in İmam Hatip schools was abandoning Islam in favour of deism. The report's publication generated large-scale controversy amongst conservative Muslim groups in Turkey. Progressive Islamic theologian Mustafa Öztürk noted the phenomenon a year prior, arguing that the "very archaic, dogmatic notion of religion" held by the majority of those claiming to represent Islam was causing "the new generations [to become] indifferent, even distant, to the Islamic worldview." Despite mostly lacking reliable statistical data, numerous anecdotes appear to point in this direction.

Although some commentators claim the secularisation is merely a result of Western influence or a potential conspiracy, most commentators, even some pro-government ones, have come to conclude that "the real reason for the loss of faith in Islam is not the West but Turkey itself: It is a reaction to all the corruption, arrogance, narrow-mindedness, bigotry, cruelty and crudeness displayed in the name of Islam." The right-wing ruling party AKP has also been commonly cited as a potential factor.[241]

In January 2006, Kamil Kiroğlu was beaten unconscious and threatened with death if he refused to reject his Christian religion and return to Islam.[6]

United Arab Emirates

[edit]Apostasy is a crime in the United Arab Emirates.[242] In 1978, UAE began the process of Islamising the nation's law, after its council of ministers voted to appoint a High Committee to identify all its laws that conflicted with Sharia. Among the many changes that followed, UAE incorporated hudud crimes of Sharia into its Penal Code – apostasy being one of them.[243] Article 1 and Article 66 of UAE's Penal Code requires hudud crimes to be punished with the death penalty.[244][245]

UAE law considers it a crime and imposes penalties for using the Internet to preach against Islam or to proselytize Muslims inside the international borders of the nation. Its laws and officials do not recognize conversion from Islam to another religion. In contrast, conversion from another religion to Islam is recognized, and the government publishes through mass media an annual list of foreign residents who have converted to Islam. Though the punishment for apostasy is death, there has been no known case of legal persecution for apostasy and no known death penalty has been applied.[246]

United Kingdom

[edit]The Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain (CEMB) is the British branch of the Central Council of Ex-Muslims, who represent former Muslims who fear for their lives because they have renounced Islam. It was launched in Westminster on 22 June 2007. The Council protests against Islamic states that still punish Muslim apostates with death under the Sharia law. The council is led by Maryam Namazie, who was awarded Secularist of the Year in 2005 and has faced death threats.[247] The British Humanist Association and National Secular Society sponsored the launch of the organisation and have supported its activities since.[248] A July 2007 poll by the Policy Exchange think-tank revealed that 31% of British Muslims believed that leaving the Muslim religion should be punishable by death.[249]

CEMB assists about 350 ex-Muslims a year, the majority of whom have faced death threats from Islamists or family members.[250] The number of ex-Muslims is unknown due to a lack of sociological studies on the issues and the reluctance of ex-Muslims to discuss their status openly.[250] Writing for The Observer, Andrew Anthony argued that ex-Muslims had failed to gain support from other progressive groups, due to caution about being labelled by other progressive movements as Islamophobic or racist.[250]

In November 2015, the CEMB launched the social media campaign #ExMuslimBecause, encouraging ex-Muslims to come out and explain why they left Islam. Within two weeks, the hashtag had been used over a 100,000 times. Proponents argued that it should be possible to freely question and criticise Islam, opponents claimed the campaign was amongst other things 'hateful', and said the extremist excrescences of Islam were unfairly equated with the religion as a whole.[251]

Besides the CEMB, a new initiative for ex-Muslims, Faith to Faithless, was launched by Imtiaz Shams and Aliyah Saleem in early 2015.[250][252]

United States

[edit]According to Pew Research Center estimate in 2017, there were about 3.5 million Muslims living in the United States,[253] comprising about 1% of the total U.S. population.[254] An estimated 100,000 of these Muslims abandon Islam each year, but roughly the same number convert to Islam.[255]

Altogether nearly a quarter (23%) of those raised in the faith have left, of whom more than half of them abandon religion entirely, while 22% now identify as Christian.[256][257] However, many of them are not open about their deconversion, in fear of endangering their relationships with their relatives and friends.[258]