Anubis Shrine

| Anubis Shrine | |

|---|---|

Materials: wood, plaster, lacquer, and gold leaf | |

| Size | Total length (including poles) 273.5 cm long, 63.7 cm high (shrine including sledge),[1] 60 cm high (jackal),[2] 50.7 cm wide (including sledge)[1] |

| Created | Reign of Tutankhamun, 18th Dynasty, New Kingdom |

| Discovered | Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62), Valley of the Kings |

| Present location | Egyptian Museum, Cairo |

| Identification | JE 61444 |

3D model (click to interact) | |

The Anubis Shrine was part of the burial equipment of the 18th Dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun, whose tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered almost intact in 1922 by Egyptologists led by Howard Carter. Today the object, with the find number 261, is on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, with the inventory number JE 61444.[2]

Discovery

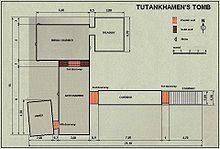

[edit]The Anubis Shrine was found behind the unwalled entrance which led from the burial Chamber to the Treasury. The shrine, with a figure of the god Anubis on top, was facing towards the west. Behind it was the large canopic shrine containing the king's canopic chest and jars. During the work in the burial chamber, the entrance to the Treasury (called the Store Room by Carter in his diaries) was blocked with wooden boards, so that the work would not damage the objects in the Store Room. Investigating and clearing the Store Room began in the fifth excavation season (22 September 1926 – 3 May 1927) and Carter first described the Anubis Shrine in his excavation journal on 23 October 1927.[3]

Anubis statue

[edit]The statue of Anubis, depicted in animal form as a recumbent jackal, is attached to the roof of the shrine. The statue is made of wood, covered with black paint. The insides of the ears, eyebrows, rims of the eyes, collar, and the band knotted around the neck are worked in gold leaf. The eyes are inlaid in gold; the whites of the eyes are made from calcite and the pupils from obsidian. The claws are made of silver.[4] A very similar Anubis statue was found in the tomb of the pharaoh Horemheb (KV57). Made of cedar, the jackal once had inlaid eyes which are now missing, and was painted black with a gilded plaster collar. The body and paw of another jackal were also found, along with two fragmentary jackal heads. Unlike Tutankhamun's jackal, the claws were made of copper.[5]

The Anubis statue was wrapped in a linen shirt which was from the seventh regnal year of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, according to an ink inscription on it. Underneath was a very fine linen gauze tied at the front of the neck. Over this were two thin floral collars of blue lotus and cornflowers, tied at the back of the neck.[4] Between the front legs sat an ivory writing palette inscribed with the name of Akhenaten's eldest daughter, Meritaten.[4]

The statue was separated from the roof of the shrine on 25 October 1926 so that it could be transported through the burial chamber. The shrine on its sledge and the jackal were moved to the laboratory two days later on 27 October.[3] The wood was noted to have shrunk over the intervening millennia, which caused the gilded surface to bulge outwards. The surfaces and weakened areas were strengthened with wax.[6]

Shrine

[edit]

The shrine on which the statue sits is trapezoidal. In his records, Howard Carter called it a pylon because of its resemblance to the monumental temple gateways. Like the jackal, the shrine is also made of wood, with a layer of plaster covered with gold leaf. The top edge has an out-curving cavetto cornice with torus molding. The sides are decorated with djed pillars, a symbol of endurance which is linked closely with the god Osiris and tyet-knots, which can stand for life, like the ankh, and is a symbol of the goddess Isis. A design of recessed niches decorates the lower edge.[1] Inscriptions run horizontally along the upper edge and vertically along the sides on all faces of the shrine. The inscriptions invoke two manifestations of Anubis: Imiut (Jmj wt – "He who is in his wrappings") and Khenti-Seh-netjer (Ḫntj-sḥ-nṯr – "The first of the god's hall").[7] Inside the shrine are four small trays and a large compartment. The small trays contained cult objects consisting of faience forelegs, two mummiform figures, figures of Ra and Thoth, a faience papyrus column, a wax figure of a bird, pieces of resin, and two calcite cups containing a mix of salt, sodium sulfate, and natron, while the large compartment contained jewelry which was wrapped in linen and sealed but had been disturbed by robbers.[4]

Function and significance

[edit]

The shrine is mounted on a sledge-shaped palanquin which has two carrying poles projecting from the front and back. It is therefore presumed that the Anubis shrine was used in the funerary procession of the Pharaoh before being placed in front of the canopic chest in the Treasury. This location and the orientation of the Anubis shrine towards the west, the direction of the afterlife in Ancient Egyptian belief, show the role of the god Anubis as guardian of the necropolis.[8] This is made clear by a small brick of unfired clay, known as a magic brick, found at the entrance to the Store Room, in front of the shrine. This was the fifth magic brick found in Tutankhamun's tomb. According to Carter, the brick was placed at the entrance to the Treasury for a reason, since the brick had a magic formula upon it, intended to protect the deceased:

It is I who hinder the sand from choking the secret chamber, and who repel that one who would repel him with the desert flame. I have set aflame the desert (?), I have caused the path to be mistaken. I am for the protection of the deceased.[3]

The inscription on this brick was the origin of the curse of the pharaohs,[9] which was propagated in the international press of the time in many different versions rather than this original translation.

The statue of the jackal lying on the shrine is in the same posture and form as one hieroglyph (Gardiner list: E16) for Anubis. However, this hieroglyph also signifies the title jnpw ḥrj-sštȝ ("Anubis over the mysteries"), apparently with a double meaning: watcher and master of mysteries.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Carter, Howard. "Object Card 261-4". Griffith Institute. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b Hawass, Zahi (2018). Tutankhamun : Treasures of the golden pharaoh : The centennial celebration. New York: Melcher Media. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-59591-100-1.

- ^ a b c Carter, Howard. "Excavation Journal 5th Season, September 22nd 1926 to May 3rd 1927". The Griffith Institute. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Carter, Howard (1933). The Tomb of Tut.Ankh.Amen Volume III: The Annexe and Treasury (Reprint, 2000 ed.). London: Duckworth. pp. 41–45.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M. (1912). The tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou (2001 reprint ed.). London: Duckworth. p. 104. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ Carter, Howard. "Object Card 261-5". Griffith Institute. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Rolf Felde, Ägyptische Gottheiten. 2nd edition. R. Felde Eigenverlag, Wiesbaden 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. ABC CLIo. p. 104.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi (2008). King Tutankhamun : The Treasures of the Tomb. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 158. ISBN 978-0500051511.

- ^ Edwards, I. E. S. (1976). Tutankhamun: His Tomb And Its Treasures. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 153.

Further reading

[edit]- Die Hauptwerke im Ägyptischen Museum in Kairo. Offizieller Katalog. Publication of the heritage service of Egypt. Von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0640-7, No. 185.

- Howard Carter. Das Grab des Tut-ench-Amun. Brockhaus, Wiesbaden 1981, V. No. 1513, ISBN 3-7653-0262-7, p. 170.

- Zahi Hawass. Anubis Shrine. (= King Tutankhamun. The Treasures Of The Tomb.) Thames & Hudson, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-500-05151-1, pp. 158–159.

- T. G. H. James:. Tutanchamun. Müller, Köln 2000, ISBN 88-8095-545-4, pp. 156–157.

- M. V. Seton-Williams: Tutanchamun. Der Pharao. Das Grab. Der Goldschatz. Ebeling, Luxembourg 1980, ISBN 3-8105-1706-2, pp. 37, 95.