Anton Webern

Anton Webern | |

|---|---|

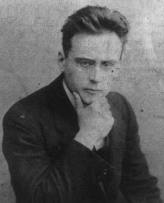

Webern in Stettin, October 1912 | |

| Born | 3 December 1883 |

| Died | 15 September 1945 (aged 61) |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

Anton Webern[a] (German: [ˈantoːn ˈveːbɐn] ; 3 December 1883 – 15 September 1945) was an Austrian composer, conductor, and musicologist. His music was among the most radical of its milieu in its concision and use of then novel atonal and twelve-tone techniques in an increasingly rigorous manner, somewhat after the Franco-Flemish School of his studies under Guido Adler. With his mentor Arnold Schoenberg and his colleague Alban Berg, Webern was at the core of those within the broader circle of the Second Viennese School.

Webern was arguably the first and certainly the last of the three to write music in a style that was both expressionist and aphoristic, reflecting his instincts and the idiosyncrasy of his compositional process. He treated themes of loss, love, nature, and spirituality, working from his experiences. Unhappily peripatetic and typically assigned light music or operetta in his early conducting career, he aspired to conduct what was seen as more respectable, serious music at home in Vienna. Following Schoenberg's guidance, Webern attempted to write music of greater length during and after World War I, relying partly on the structural support of texts in many Lieder.

He rose as a choirmaster and conductor in Red Vienna with David Josef Bach's support, championing Gustav Mahler's music at home and abroad. With a publication contract through Emil Hertzka at Universal Edition and Schoenberg away in Berlin, Webern began writing music of increasing confidence, independence, and scale using twelve-tone technique. He maintained his "path to the new music" while marginalized as a "cultural Bolshevist" in Fascist Austria and Nazi Germany, enjoying some international recognition but relying more on teaching[b] for income. Struggling to reconcile his loyalties to his divided friends and family, he adopted an optimistic outlook on the future under Nazi rule that wore on him as it proved wrong, and he repeatedly considered emigrating.

A soldier shot and killed Webern in an apparent accident shortly after World War II in Mittersill. His music was then celebrated by composers who took it as a point of departure in a phenomenon known as post-Webernism, closely linking his legacy to serialism. Musicians and scholars like Pierre Boulez, Robert Craft, and Hans and Rosaleen Moldenhauer studied and organized performances of his music, establishing it as modernist repertoire. Broader understanding of his expressive agenda, performance practice, and complex sociocultural and political contexts lagged. An historical edition of his music is currently in progress.

Biography

[edit]1883–1908: Upbringing between late Imperial Vienna and countryside

[edit]- (left) A brick barn in a field of wildflowers on the Preglhof estate[16]

- (right) Pfarrkirche Schwabegg and southern foothills across from a snowy field

Bucolic Heimat

[edit]Webern was born in Vienna, Austria-Hungary. He was the only surviving son of Carl von Webern, a descendant of minor nobility, high-ranking civil servant, mining engineer,[17] and owner of the Lamprechtsberg copper mine in the Koralpe. Much of Webern's early youth was in Graz (1890–1894) and Klagenfurt (1894–1902), though his father's work briefly took the family to Olmütz and back to Vienna.[18]

His mother Amalie (née Geer) was a pianist and accomplished singer. She taught Webern piano and sang opera with him. He received first drums, then a trumpet, and later a violin as Christmas gifts. With his sisters Rosa and Maria, Webern danced to music and ice-skated the Lendkanal to the Wörthersee. Edwin Komauer taught him cello, and the family played chamber music, including that of Mozart, Schubert, and Beethoven.[19] Webern learned to play Bach's cello suites[20] and may have studied Bach's polyphony under Komauer.[21]

The extended Webern family spent summers,[c] holidays, and vacations at their country estate, the Preglhof. The children played outside in the forest and on a high meadow with pasture grazed by herded cattle and with a church-and-mountain view; they bathed in a pond (where Webern once saved Rosa from drowning). He drove horses to Bleiburg and fought a wildfire encroaching on the estate.[19] These experiences and reading Peter Rosegger's Heimatkunst shaped Webern's distinct and lasting sense of Heimat.[22]

University

[edit]After a trip to Bayreuth,[23] Webern studied musicology at the University of Vienna (1902–1906) with Guido Adler, a friend of Mahler, composition student of Bruckner,[d] and devoted Wagnerian who had been in contact with both Wagner and Liszt.[24][e] He quickly joined the Wagner Society, meeting popular conductors and musicians.[25] Egon Wellesz recalled he and Webern analyzed Beethoven's late quartets at the piano in Adler's seminars.[f] Webern learned the historical development of musical styles and techniques, editing the second volume of Heinrich Isaac's Choralis Constantinus as his doctoral thesis.[g] Hans and Rosaleen Moldenhauer noted Webern's scholarly engagement with Isaac's music as a formative experience for Webern the composer. Webern especially praised Isaac's voice leading or "subtle organization in the interplay of parts":

The voices proceed ... in ... equality ... . Each ... has its own development and is a ... self-contained ... structural unit ... . ... Isaac uses ... canonic devices in ... profusion ... . ... Added ... is the keenest observation of tone colourings in ... registers of the human voice. This is partly the cause of ... interlacing of voices and ... their movement by leaps.[28]

Webern studied art history and philosophy under professors Max Dvořák, Laurenz Müllner, and Franz Wickhoff,[29] joining the Albrecht Dürer Gesellschaft[h] in 1903.[23] His cousin Ernst Diez, an art historian studying in Graz, may have led him to the work of Arnold Böcklin and Giovanni Segantini, which he admired along with that of Ferdinand Hodler and Moritz von Schwind.[30] Webern idolized Segantini's landscapes on a par with Beethoven's music, diarying in 1904:

I long for an artist in music such as Segantini was in painting. ... [F]ar away from all turmoil of the world, in contemplation of the glaciers, of eternal ice and snow, of ... mountain giants. ... [A]n alpine storm, ... the radiance of the summer sun on flower-covered meadows—all these ... in the music, ... of alpine solitude. That man would ... be the Beethoven of our day.[31]

Webern also studied nationalism and Catholic liturgy,[25] shaped by his mostly provincial Catholic upbringing, which provided little exposure to the relatively cosmopolitan people of Vienna.[32] At the time, antisemitism was resurging in Austria, fueled by Catholic resentment after Jewish emancipation in the 1867 December Constitution.[33] Initially, Webern viewed his Jewish peers as ostentatious and unfriendly, but his attitude shifted by 1902.[34] He quickly and durably made many close friends, most of them Jewish; Kathryn Bailey Puffett wrote that this likely affected his views.[35]

Schoenberg and his circle

[edit]In 1904, Webern approached Hans Pfitzner for composition lessons but left angrily when Pfitzner criticized Mahler and Richard Strauss.[36] Adler admired Schoenberg's work and may have[i] sent Webern to him for composition lessons.[38] Thus Webern met Berg, another Schoenberg pupil, and Schoenberg's brother-in-law Alexander Zemlinsky, through whom Webern may have worked as an assistant coach at the Volksoper in Vienna (1906–1909).[39] Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern became devoted, lifelong friends with similar musical trajectories.[40] Adler, Heinrich Jalowetz, and Webern played Schoenberg's quartets under the composer, accompanying Marie Gutheil-Schoder in rehearsals for Op. 10.[41]

Also through Schoenberg, who painted and had a 1910 solo exhibition at Hugo Heller's bookstore, Webern met Gustav Klimt, Oskar Kokoschka, Max Oppenheimer (with whom he corresponded on ich–Du terms), Egon Schiele, and Emil Stumpp.[42] In 1920, Webern wrote Berg about the "indescribable impression" Klimt's work made on him, "that of a luminous, tender, heavenly realm".[43][j] He also met Karl Kraus, whose lyrics he later set, but only to completion in Op. 13/i.[45]

1908–1918: Early adulthood in Austria-Hungary and German Empire

[edit]Marriage

[edit]Webern married Wilhelmine "Minna" Mörtl in a 1911 civil ceremony in Danzig. She had become pregnant in 1910 and feared disapproval, as they were cousins. Thus the Catholic Church only solemnized their lasting union in 1915, after three children.[46]

They met in 1902,[47] later hiking along the Kamp from Rosenburg-Mold to Allentsteig in 1905. He wooed her with John Ruskin essays (in German translation), dedicating his Langsamer Satz to her. Webern diaried about their time together "with obvious literary aspirations":

We wandered ... The forest symphony resounded. ... A walk in the moonlight on flowery meadows—Then the night—"what the night gave to me, will long make me tremble."—Two souls had wed.[k]

Early conducting career

[edit]Webern conducted and coached singers and choirs mostly in operetta, musical theater, light music, and some opera in his early career. Operetta was in its Viennese Silver Age.[49] Much of this music was regarded as low-[50] or middlebrow; Kraus, Theodor Adorno, and Ernst Krenek found it "uppity" in its pretensions.[51][l] In 1924 Ernst Décsey recalled he once found operetta, with its "old laziness and unbearable musical blandness", beneath him.[53] J. P. Hodin contextualized the opposition of the "youthful intelligentsia" to operetta with a quote from Hermann Bahr's 1907 essay Wien:[54]

everyone knows ... it is always Sunday in Vienna ... one lives in a world of half-poetry which is very dangerous for the real thing. They can recognize a few waltzes by Lanner and Strauss ... a few Viennese songs ... It is a well-known fact that Vienna has the finest cakes ... and the most cheerful, friendly people. ... But those who are condemned to live here cannot understand all this.

"What benefit ... if all operettas ... were destroyed", Webern told Diez in 1908.[55] But in 1912, he told Berg that Zeller's Vogelhändler was "quite nice" and Schoenberg that J. Strauss II's Nacht in Venedig was "such fine, delicate music. I now believe ... Strauss is a master."[56] A summer 1908 engagement with Bad Ischl's Kurorchester was "hell".[55] Webern walked out on an engagement in Innsbruck (1909), writing in distress to Schoenberg:

a young good-for-nothing ... my 'superior!' ... what do I have to do with such a theatre? ... do I have to perform all this filth?[57][m]

Webern wrote Zemlinsky seeking work at the Berlin or Vienna Volksoper instead.[59][n] He started at Bad Teplitz's Civic Theater in early 1910, where the local news reported his "sensitive, devoted guidance" as conductor of Fall's Geschiedene Frau, but he quit within months due to disagreements.[61] His repertoire likely included Fall's Dollarprinzessin, Lehár's Graf von Luxemburg, O. Straus's Walzertraum, J. Strauss II's Fledermaus, and Schumann's Manfred.[62] There were only 22 musicians in the orchestra, too few to perform Puccini's operas, he noted.[62]

Webern then summered at the Preglhof, composing his Op. 7 and planning an opera.[63] In September, he attended the Munich premiere of Mahler's Symphony of a Thousand and visited with his idol,[o] who gave Webern a sketch of "Lob der Kritik".[p] Webern then worked with Jalowetz as assistant conductor in Danzig (1910–1911), where he first saw the "almost frightening" ocean.[66] He conducted von Flotow's Wintermärchen, George's Försterchristl, Jones' Geisha, Lehár's Lustige Witwe, Lortzing's Waffenschmied, Offenbach's Belle Hélène, and J. Strauss II's Zigeunerbaron.[67] He particularly enjoyed Offenbach's Contes d'Hoffmann and Rossini's Barbiere di Siviglia, but only Jalowetz was allowed to conduct this more established repertoire.[68]

Webern soon expressed homesickness to Berg; he could not bear the separation from Schoenberg and their world in Vienna.[69] He returned after resigning in spring 1911, and the three were pallbearers at Mahler's funeral in May 1911.[70] Then in summer 1911, a neighbor's antisemitic abuse and aggression caused Schoenberg to quit work, abandon Vienna, and go with his family to stay with Zemlinsky on the Starnbergersee.[71] Webern and others fundraised for Schoenberg's return, circulating more than one hundred leaflets with forty-eight signatories, including G. Adler, H. Bahr, Klimt, Kraus, and R. Strauss, among others.[72][q] But Schoenberg was resolved to move to Berlin, and not for the first or last time, convinced of Vienna's fundamental hostility.[74]

Webern soon joined him (1910–1912), finishing no new music in his devoted work on Schoenberg's behalf, which entailed many editing and writing projects.[75] He gradually became tired, unhappy, and homesick.[75] He tried to persuade Schoenberg to return home to Vienna, continuing the fundraising campaign and lobbying for a position there for Schoenberg, but Schoenberg could not bear to return to the Akademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst due to his prior experiences in Vienna.[76] At the same time, Webern began a cycle of repeatedly quitting and being taken back by Zemlinsky at the Deutsches Landestheater Prague (1911–1918).[77]

He had a short-lived conducting post in Stettin (1912–1913), which, like all the others, kept him from composing and alienated him.[78] On the verge of a breakdown, he wrote Berg shortly after arriving (Jul. 1912):[79]

I find myself under the dregs of mankind ... with ... absurd music; I'm ... seriously ill. My nerves torture me ... . I want to be far away ... . In the mountains. There everything is clear, the water, the air, the earth. Here everything is dismal. I'm poisoned by drinking the water.

"Old song" of "lost paradise"

[edit]Webern's father sold the Preglhof in 1912, and Webern mourned it as a "lost paradise".[80] He revisited it and the family grave in nearby Schwabegg his entire life, associating these places with the memory of his mother, whose 1906 loss profoundly affected him.[81] In July 1912, he confided in Schoenberg:

I am overwhelmed with emotion when I imagine everything ... . My daily way to the grave of my mother. The infinite mildness of the entire countryside, all the thousand things there. Now everything is over. ... If only you could ... have seen ... . The seclusion, the quiet, the house, the forests, the garden, and the cemetery. About this time, I had always composed diligently.[82]

Shortly after the anniversary of his mother's death, he wrote Schoenberg in September 1912:[82]

When I read letters from my mother, I could die of longing for the places where all these things have occurred. How far back and ... beautiful. ... Often a ... soft ... radiance, a supernatural warmth falls upon me— ... from my mother.[82]

For Christmas in 1912, Webern gifted Schoenberg Rosegger's Waldheimat (Forest Homeland[83]), from which Johnson highlighted:

Childhood days and childhood home!

It is that old song of Paradise. There are people for whom ... Paradise is never lost ... in them God's kingdom ... rises ... more ... in ... memory than ... ever ... in reality; ... children are poets and retrace their steps.[84]

Rosegger's account of his mother's death at the book's end ("An meine Mutter") resonated with Webern, who connected it to his Op. 6 orchestral pieces.[85] In a January 1913 letter to Schoenberg, Webern revealed that these pieces were a kind of program music, each reflecting details and emotions tied to his mother's death.[85] He had written Berg in July 1912, "my compositions ... relate to the death of my mother", specifying in addition the "Passacaglia, [String] Quartet, most [early] songs, ... second Quartet, ... second [orchestral pieces, Op. 10] (with some exceptions)".[86][r]

Julian Johnson contended that Webern understood his cultural origins with a maternal view of nature and Heimat, which became central themes in his music and thought.[88] He noted that Webern's deeply personal idea of a maternal homeland—built from memories of pilgrimages to his mother's grave, the "mild", "lost paradise" of home, and the "warmth" of her memory—reflected his sense of loss and his yearning for return.[89] Drawing loosely on V. Kofi Agawu's semiotic approach to classical music, specifically his idea of musical topics, Johnson held that all of Webern's music, though rarely directly representational, was enriched by its associative references and more specific musical and extra-musical meanings.[90] In this he claimed to echo Craft, Jalowetz, Krenek, the Moldenhauers, and Webern himself.[91]

In particular, Webern associated nature with his personal (often youthful and spiritual) experiences, forming a topical nexus that recurred in his diaries, letters, and music, sometimes explicitly in sketches and set texts. He frequented the surrounding mountains, summering in resort towns like Mürzzuschlag and backpacking (sometimes summiting) the Gaisstein, Grossglockner, Hochschober, Hochschwab, and Schneealpe (among others) throughout his life. The alpine climate and föhn, glaciers, pine trees, and springs "crystal clear down to the bottom" fascinated him. He treasured this time "up there, in the heights", where "one should stay".[92]

He collected and organized "mysterious" alpine herbs and cemetery flowers in pressed albums, and he tended gardens at his father's home in Klagenfurt and later at his own homes in the Mödling District (first in Mödling, then in Maria Enzersdorf).[93] Karl Amadeus Hartmann remembered that Webern gardened "as a devotion" to Goethe's Metamorphosis of Plants, and Johnson drew a parallel between Webern's gardening and composing, emphasizing his connection to nature and his structured, methodical approach in both pursuits.[94] Johnson noted that gardens and cemeteries are alike in being cultivated, closed spaces of rebirth and quiet reflection.[95]

These habits and preoccupations endured in Webern's life and œuvre.[88] In 1933, Joseph Hueber recalled Webern stopped in a fragrant meadow, dug his hands into the soil, and breathed in the flowers and grass before rising to ask: "Do you sense 'Him' ... as strongly as I, 'Him, Pan'?"[96] In 1934, Webern's lyricist and collaborator Hildegard Jone described his work as "filled ... with the endless love and delicacy of the memory of ... childhood". Webern told her, "through my work, all that is past becomes like a childhood".[97]

Psychotherapy

[edit]In 1912–1913, Webern had a breakdown and saw Alfred Adler, who noted his idealism and perfectionism.[98] There were many factors involved.[99] Webern had little time (mostly summers) to compose.[100] There were conflicts at work (e.g., he emphasized that a director called him a "little man").[101] His ambivalence toward sales-oriented popular music theater contributed ("I ... stir the sauce", he wrote).[101] "It appears ... improbable that I should remain with the theatre. It is ... terrible. ... I can hardly ... adjust to being away from home", he had written Schoenberg in 1910.[102] Miserably ill and alienated, he had first sought medical advice and took rest at a sanatorium in Semmering.[103] Adler evaluated his symptoms as psychogenic responses to unmet expectations.[98] Webern wrote Schoenberg that Adler's psychoanalysis was helpful and insightful.[98]

World War I

[edit]As World War I broke out and nationalist fervor swept Europe, Webern found it "inconceivable", he wrote Schoenberg in August 1914, "that the German Reich, and we along with it, should perish."[104] Yielding in his distrust of Protestant Germany, he compared Catholic France to "cannibals" and expressed pan-German patriotism amid wartime propaganda.[105] He cited his "faith in the German spirit" as having "created, almost exclusively, the culture of mankind".[106] Despite his high regard of French classical music, especially Debussy's, Webern revered the tradition as centered on counterpoint and form, and as mainly German since Bach.[107]

Webern served intermittently for nearly two years.[108] The war cost him professional opportunities, much of his social life, and the necessary leisure time to compose (he completed only nine Lieder).[108] Moving frequently and tiring,[109] he began to despair, explaining to Schoenberg in November 1916 that the reality of war was "Old Testament" and "'Eye for eye'", "as if Christ had never existed".[110] Webern was discharged in December 1916 for myopia, which had disqualified him from frontline service.[111]

His 1917 Lieder show that he reflected on his patriotism and processed his sorrow.[112] He treated the loss of life and, with the 1916 death of Franz Joseph I of Austria, the end of an era.[113] In "Fahr hin, o Seel'", he selected a lament sung at a funeral in a Rosegger novel.[114] In "Wiese im Park", he selected a text from Kraus recognizing that the day was "dead", "und alles ... so alt"[114] ("and everything ... so old"). Webern also set several disturbing poems of Georg Trakl, not all of which he could finish.[115] With uninterrupted contrapuntal density, by turns muscular and murmured, he word painted Trakl's "great cities" and "dying peoples", "leafless trees", "violent alarm", and "falling stars" in "Abendland III".[112]

Austrian defeat and socioeconomic strain

[edit]During and after the end of the war, Webern, like other Austrians, contended with food shortages, insufficient heating, socioeconomic volatility, and geopolitical disaster in defeat.[116] He had considered retreating to the countryside and purchasing a farm since 1917, specifically as an asset better than war bonds at shielding his family's wealth from inflation.[117] (In the end, he lost all that remained of his family's wealth to hyperinflation by 1924.)[116] He proposed to Schoenberg that they might be smallholders together.[117]

Despite Schoenberg's and his father's advice that he not quit conducting, Webern followed to Schoenberg to Mödling in early 1918, hoping to be reunited with his mentor and to compose more.[118] But Webern's finances were so poor that he soon explored a "voluntary exile" to Prague again.[117] Nonetheless, he continued to raise funds, including his own, for Schoenberg,[117] with whom he spent every day.[119]

Yet soon after he arrived, Webern broke his friendship with Schoenberg.[120][s] The break was multifactorial[124] but involved Webern's dissatisfaction with his career[125] and financial turmoil.[126] Berg learned of the Weberns' ill temperaments and "latent antisemitism" from Schoenberg,[127][t] and noted that Schoenberg "wouldn't explain" further than "'Webern wants to go to Prague again'".[119] Bailey Puffett argued that Webern's actions in and after the 1930s suggested that he was not antisemitic, at least in his maturity.[132] She noted that Webern later wrote Schoenberg that he felt "a sense of the most vehement aversion" against German-speaking people who were.[133]

After meeting with Webern, Berg saw "the matter in a different light", considering Webern "by and large innocent" in light of what Webern said was Schoenberg's "kick in the teeth": after laying plans for a New Music society, Schoenberg was angry upon learning that Webern was instead considering Prague again,[117] calling him "secretive and deceitful".[134] They reconciled in October 1918, not long before Webern's father died in 1919.[135] Webern was changed by these events; he slowly began to grow more independent of Schoenberg, who was like a father to him.[136] For his part, Schoenberg was not infrequently dubious of Webern, who he still considered his closest friend.[137][u]

1918–1933: Rise in Rotes Wien (Interwar Vienna)

[edit]Society for Private Musical Performances

[edit]Webern stayed in Vienna and worked with Berg, Schoenberg, and Erwin Stein at the Society for Private Musical Performances (1918–1921), promoting new music through performances and contests. Music included that of Bartók, Berg, Busoni, Debussy,[v] Korngold, Mahler, Novák, Ravel, Reger, Satie, Strauss, Stravinsky, and Webern himself. Webern wrote Berg about Stravinsky's "indescribably touching" Berceuses du chat and "glorious" Pribaoutki, which Schoenberg conducted at a sold-out 1919 Society concert.[139] There was perhaps some shared influence among Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Webern at this time.[140] The Society dissolved amid hyperinflation in 1921, having boasted some 320 members and sponsored more than a hundred concerts.[122]

Mature conducting career

[edit]

Webern obtained work as music director of the Wiener Schubertbund 1921, having made an excellent impression as a vocal coach Schoenberg recommended for their 1920 performance of Gurre-Lieder.[141] They nearly abandoned this project before Webern stepped in.[141] He led them in performances of Brahms, Mahler, Reger, and Schumann, among others.[141] But low salary, mandatory touring, and challenges to Webern's thorough rehearsals prompted him to resign in 1922.[141] He was also chorusmaster of the Mödling Männergesangverein[w] (1922–1926) until he resigned in controversy over hiring a Jewish soprano, Greta Wilheim, as a stand-in soloist for Schubert's Mirjams Siegesgesang.[142]

From 1922, Webern led the mixed-voice amateur Singverein der Sozialdemokratischen Kunstelle[x] and Arbeiter-Sinfonie-Konzerte[y] through David Josef Bach, Director of the Sozialdemokratische Kunststelle.[143][z] Webern won DJ Bach's confidence with a 1922 performance of Mahler's Symphony No. 3 that established his reputation, prompting Berg to praise him as "the greatest conductor since Mahler himself".[144][aa] Webern's Mahler interpretations continued to be widely celebrated.[146][ab] From 1927, RAVAG aired twenty-two of Webern's performances.[151]

He premiered Berg's Chamber Concerto with soloists Rudolf Kolisch and Eduard Steuermann in 1927[152] and led Stravinsky's Les Noces with Erich Leinsdorf among the pianists in 1933.[153][154][ac] Armand Machabey noted Webern's regional reputation as a conductor of "haute valeur"[ad] for his meticulous approach to then contemporary music, comparing him to Willem Mengelberg in Le Ménestrel (1930).[162] Some on the left, notably Oscar Pollak in Der Kampf (1929), criticized Webern's programming as more ambitious and bourgeois than popular and proletarian.[163] And Webern seemed uneasy in his dependence on the Social Democrats for conducting work, perhaps on religious grounds, Krenek speculated.[164] But Walter Kolneder wrote that "Artistic work for and with workers was [from] a ... Christian standpoint which Webern took very seriously".[165]

Relative success in a destabilizing society

[edit]Webern's finances were often precarious, even in his years of relative success. Relief came from family, friends, patrons, and prizes.[166] He twice received the Preis der Stadt Wien für Musik.[ae] To compose more, he sought income while trying not to overcommit himself as a conductor.[170] He contracted with Universal Edition only after 1919, reaching better terms in 1927,[171] but he was not very ambitious or astute in business.[172] Even with a doctorate and Guido Adler's respect, he never secured a remunerative university position, whereas in 1925 Schoenberg was invited to the Prussian Academy of Arts, ending their seven years together in Mödling.[27]

Social Democrat–Christian Social relations polarized and radicalized amid the Schattendorfer Urteil.[173] Webern and others[af] signed an "Announcement of Intellectual Vienna"[ag] published on the front page of the Social Democrats' daily Arbeiter-Zeitung[ah] days before the 1927 Austrian legislative election.[174] On Election Day in Die Reichspost, Ignaz Seipel of the Einheitsliste officially applied the term "Red Vienna" pejoratively, attacking Vienna's educational and cultural institutions.[175] Social unrest escalated to the July Revolt of 1927 and beyond.[175] Webern's nostalgia for social order intensified with increasing civil disorder.[176] In 1928 friends fundraised for him, partly to fund a rest cure at the Kurhaus Semmering for his exhaustion and (possibly psychosomatic) gastrointestinal complaints.[ai]

In 1928, Berg celebrated the "lasting works" and successes of composers "whose point of departure was ... late Mahler, Reger, and Debussy and whose temporary end point is in ... Schoenberg" in their rise from "pitiful 'cliques'" to a large, diverse, international, and "irresistible movement".[178] But they were soon marginalized and ostracized in Central Europe with few exceptions,[179][aj] and in 1929 Webern wrote Schoenberg that "it is getting worse and worse here".[181] He declined a RAVAG executive role, citing time constraints and fearing further affiliation with the Social Democrats.[182][ak]

Webern's music was performed and publicized more widely starting in the latter half of the 1920s.[184] Yet he found no great success as Berg enjoyed with Wozzeck[185] nor as Schoenberg did, to a lesser extent, with Pierrot lunaire or in time with Verklärte Nacht. His Symphony, Op. 21, was performed as a chamber piece in New York by the League of Composers (1929) and separately in London at the 1931 International Society for Contemporary Music (ISCM) Festival. Louis Krasner sensed some resentment, noting that Webern had "very little".[186] Krenek's impression was that Webern resented his financial hardships and lack of wider recognition.[164]

1933–1938: Perseverance in Schwarzes Wien (Austrofascist Vienna)

[edit]Marginalization at home

[edit]Financial crises, complex social and political movements, pervasive antisemitism, culture wars, and renewed military conflicts[al] continued to shape Webern's world, profoundly circumscribing his life.[187] Shortly after Webern conducted the Brecht–Eisler Solidaritätslied in 1933, Engelbert Dollfuss saw the Kriegswirtschaftliches Ermächtigungsgesetz passed, and choir singers' homes were raided.[188] In the 1934 Austrian Civil War, Austrofascists[am] executed, exiled, and imprisoned Social Democrats, outlawed their party, and abolished cultural institutions.[190]

Stigmatized by his decade-long association with Social Democrats, Webern lost a promising domestic conducting career, which might have been better recorded.[191] He eventually abandoned efforts with what remained of the workers' choir in the form of the much constrained Freie Typographia in 1935,[192] instead working as a UE editor and IGNM-Sektion Österreich board member and president (1933–1938, 1945).[193]

Amid wars and crises, antisemitism had grown to epidemic proportions by the late 1920s.[194] Vienna's modern and popular culture, including the music of Webern, Schoenberg, and Berg, was of a typically Jewish milieu.[194] It was derided as Jewish in a pejorative sense, marking it as foreign by contrast to the conservatism and traditionalism of the Austrian countryside.[194] Webern's admission to the Prussian Academy of Arts was withdrawn as Adolf Hitler rose in Germany,[188] and an Austrian Gauleiter named Berg and Webern as Jewish composers on Bayerischer Rundfunk in 1933.[195][an] In the late 1930s, they were exhibited for their "Entartete Musik" in Nazi Germany[200][ao] and then at the Vienna Künstlerhaus in Nazi Austria.[202]

Webern delivered an eight-lecture series Der Weg zur Neuen Musik[ap] at Rita Kurzmann-Leuchter's and her physician husband Rudolf Kurzman's home (Feb.–Apr. 1933).[204] He attacked fascist cultural policy, asking "What will come of our struggle?" He observed that "'cultural Bolshevism' is the name given to everything that is going on around Schoenberg, Berg, and myself (Krenek too)"[aq] and warned, "Imagine what will be destroyed, wiped out, by this hate of culture!"[206] He lectured more at the Kurzmann-Leuchter home, privately in 1934–1935 on Beethoven's piano sonatas to about 40 attendees and later in 1937–1938.[207]

Persevering, Webern wrote Krenek that "art has its own laws ... if one wants to achieve something in it, only these laws and nothing else can have validity";[ar] upon completing Op. 26 (1935), he wrote DJ Bach, "I hope it is so good that (if people ever get to know it) they will declare me ready for a concentration camp or an insane asylum!"[209] The Vienna Philharmonic nearly refused to play Berg's Violin Concerto (1936).[as] Peter Stadlen's 1937 Op. 27 premieres were the last Viennese Webern performances until after World War II.[211] The critical success of Hermann Scherchen's 1938 ISCM London Op. 26 premiere encouraged Webern to write more cantatas and reassured him after a cellist quit Op. 20 mid-performance, declaring it unplayable.[212]

Besieged milieu and political uncertainty

[edit]Webern's milieu comprised increasingly vast differences.[213] Like most Austrians, he and his family were Catholic, though not church regulars; Webern was perhaps devout if unorthodox.[214] They became politically divided.[at] His friends (e.g., then Zionist Schoenberg,[au] left-leaning Berg[av]) were of a mostly Jewish milieu from late Imperial to "red" (Social Democratic) Vienna.[222] Alma Mahler, Krenek, Willi Reich, and Stein preferred or supported the "lesser evil"[aw] of the Austrofascists (or aligned Italian fascists) vis-à-vis the Nazis.[224] Presuming power would moderate Hitler, Webern mediated among friends with an optimistic, perhaps self-soothing, complacency, exasperating those who were at risk.[225]

Webern found himself surrounded mostly by one side as Schoenberg immigrated to the US (1933), Rudolf Ploderer died by suicide (1933),[ax] Berg died (1935), and DJ Bach, among others (e.g., Greissle, Jalowetz, Krenek, Reich, Steuermann, Wellesz), fled or worse.[227] Webern immediately considered following Schoenberg in immigrating to the US.[228] Though he sought opportunities there for Webern, Schoenberg discouraged it.[229] He knew that Webern was not eager to leave home, and he told Webern that conditions there were poor, mentioning the ongoing Great Depression.[229]

Webern's views of National Socialism have been variously described.[ay] His published items[az] reflected his audience or context.[231] Secondary literature reflected limited evidence or ideological orientations[ba] and admitted uncertainty.[233] Julie Brown noted hesitancy to approach the topic and echoed the Moldenhauers, considering the issue "vexed" and Webern a "political enigma".[234] Bailey Puffett considered Webern's politics "somewhat vague" and his situation "complex", noting that he seemed to avoid definitive political association as a practical strategy.[235] The matter had been sensationalized on the basis of limited evidence (mostly letters), Johnson wrote, sometimes with the larger aim of politicizing Webern's music and his musical language.[236]

Krasner and the Moldenhauers surmised Webern's cognitive dissonance, finding him "idealistic and rather naive".[237] In 1943 Kurt List described Webern as "utterly ignorant" and "perpetual[ly] confus[ed]" about politics, "a ready prey to the personal influence of family and friends".[bb] Johnson described him as "personally shy, a man of private feeling and essentially apolitical",[240] and as "prone to identify with Nazi politics as ... other ... Austrians".[241] Webern may have believed that the Nazis shared his own ideals, Johnson wrote, explaining that "it is possible that ... naiveté, ... ignorance and ... adherence to his own beliefs allowed Webern to see in Nazi ideology only ... elements ... he wanted to find".[242]

Visiting conducting career

[edit]Webern conducted nine concerts as a BBC Symphony visiting conductor (1929–1936). A talkie on his first London visit inspired him to ask Steuermann about writing film music, and Steuermann wrote his relatives in the film industry, Salka Viertel and Berthold Viertel, for their suggestions.[243] For the BBC, Webern selected then little-known Mahler (including both nocturnes from the Symphony No. 7 in 1934).[244] He insisted on rehearsing at the piano with vocalists and was criticized for coaching musical phrasing.[244]

In Barcelona, he withdrew from the 1936 world premiere of Berg's Violin Concerto, grief-stricken after Berg's death and overwhelmed by difficulties.[245] There Krasner recalled,

[Webern] pleaded and exhorted the players to feel the inner expressive content of one, two, or three notes at a time—rehearsing repeatedly a single motif, one bar of music and only finally, a two- or four-bar phrase.

The two then played the concerto in London with BBC musicians, who rehearsed before Webern conducted. Kenneth Anthony Wright noted Webern's "funny little explanations of the varying dynamics and flexibility of tempo", but "every syllable and every gesture of Webern was understood and lovingly heeded", Krasner recalled. The musicians "all admired and respected Webern", according to Sidonie Goossens. But Felix Aprahamian, Benjamin Britten, and Berthold Goldschmidt criticized Webern's conducting, and BBC management did not invite him back after 1936.[245][bc]

1938–1939: Inner emigration in Nazi Germany

[edit]Anschluss

[edit]Krasner's last visit with Webern was interrupted by Kurt Schuschnigg's broadcast speech that the Anschluss was imminent.[246] Krasner had been playing some of Schoenberg's Violin Concerto for Webern and trying to convince him to write a sonata for solo violin.[247] When Webern turned on the radio and heard this speech, he urged Krasner to flee.[248] Because Webern's family included Nazis, Krasner wondered whether Webern had already known that the Anschluss was planned for that day.[249] He also wondered whether Webern's warning had been solely for his safety or whether it had also been to save Webern the embarrassment of the violinist's presence in the event of celebration at the Webern home.[250]

Much of Austria did celebrate.[251] But Webern made only a terse note of the Anschluss in his notebook without registering any clear emotion.[252] In fact, he wrote Jone and her husband Josef Humplik asking not to be disturbed as he was "totally immersed" in work on Op. 28.[253] Thus, Bailey Puffett suggested that Webern may have received Krasner's visit as a distraction.[254]

By now, Hartmut Krones wrote, Webern likely realized his error in anticipating the Nazis' self-moderation.[188] Bailey Puffett proposed that Krasner, with the benefit of hindsight from the perspective of his 1987 account, may have resented Webern for "refusing to see the reality of Hitler's antisemitism", at least until apparently after 1936.[254] That year, Webern had insisted that Krasner and he travel through Nazi Germany to stop at a Munich train station café, where Krasner said "anything untoward was the least likely to happen", in an attempt to demonstrate the lack of danger.[255]

Support for the Anschluss rested on antisemitism, economic prospects,[bd] and the idea of a Greater Germany.[257][be] Under some duress, Theodor Innitzer ushered in Catholic support.[267] The Austrian Nazis and Social Democrats, both outlawed, were linked in opposition to the Austrofascists.[268] Karl Renner supported unification as a matter of self-determination before the years (1933–1938) of Gleichschaltung and Nazi soft power,[bf] and he and others now supported (or accepted as inevitable) the 1938 Anschluss.[270] Otto Bauer, in exile, expressed some acceptance with profound resignation and misgivings, having worked toward Austria's German incorporation since Provisional National Assembly's 1918 vote.[271] Webern had long shared in common pan-German sentiments, especially during wartime.[272] He also likely hoped to conduct again, securing a firmer future for his family under a new regime proclaiming itself "socialist" no less than nationalist.[273] According to what Josef Polnauer, a fellow early Schoenberg pupil, historian, and librarian, told the Moldenhauers, Webern's optimism was not dispelled until 1941.[274]

Krasner emphasized Webern's "naiveté" but acknowledged that he himself had been "foolhardy" as to the danger of antisemitism, recalling "read[ing] in the papers ... denials" and "want[ing] to see for myself" in 1938.[275][bg] Consensus had emerged on the center, left, and in some mainstream Jewish organizations that antisemitism was only a means to political power since its 1890s definition as the "socialism of fools".[277] The Frankfurt School first treated it within the rubric of class conflict (Adorno began to consider it otherwise in his 1939 "Fragments on Wagner"),[278] and Franz Neumann briefly contended that the Nazis would "never allow a complete extermination of the Jews" in his 1942 Behemoth (before revisions in 1944).[277]

Kristallnacht and recoil

[edit]Kristallnacht shocked Webern,[279] who thought that reports of Nazi atrocities were politicized, unreliable propaganda.[280] He visited and aided Jewish colleagues DJ Bach, Otto Jokl, Polnauer, and Hugo Winter.[279] For Jokl, a former Berg pupil, Webern wrote a recommendation letter to facilitate emigration. When that failed, Webern served as his godfather in a 1939 baptism.[281] Polnauer, whose emigration Mark Brunswick, Schoenberg, and Webern were unable to secure,[282] managed to survive the Holocaust as an albino; he later edited a 1959 UE publication of Webern's correspondence from this time with Humplik and Jone.[283] Webern moved Humplik's 1929 gift of a Mahler bust to his bedroom,[284] having told Felix Greissle in 1936 or 1937 that Mahler's time would come within a German Kulturnation,[285] and DJ Bach that "not all Germans are Nazis".[286]

Webern found himself increasingly alone,[287] with "almost all his friends and old pupils ... gone",[288] and his financial situation was poor. He talked to Polnauer about emigrating but was reluctant to leave home and family.[289] He entered a period of "inward emigration" and focused on composition,[290] writing to artist Franz Rederer in 1939, "We live completely withdrawn. I work a lot."[281] He corresponded extensively to maintain relationships, imploring his student George Robert to play Schoenberg in New York[291] and expressing his loneliness and isolation to Schoenberg.[292] Then war limited postal service,[293] disrupting their direct correspondence completely by 1941.

1939–1945: Hope and disillusionment during World War II

[edit]Swiss and Reich prospects

[edit]Webern's mature music was performed mostly outside the Reich, where only his tonal music and arrangements were allowed as works not in the style of a "Judenknecht". His arrangement of two of Schubert's German Dances was performed in Leipzig and broadcast in the Reich and Fascist Italy (1941).[294] His Passacaglia was considered for a Viennese contemporary music festival in 1942, Karl Böhm or Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting, but this did not happen.[294] Hans Rosbaud likely performed it in occupied Strasbourg that year, and Luigi Dallapiccola sought to have it performed in Venice in 1943.[294] Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt planned Webern's arrangement of the six-voice ricercar from Bach's Musical Offering at the Deutsche Oper Berlin in 1943, but war intervened.[294]

Supported by IGNM-Sektion Basel, the Orchester Musikkollegium Winterthur, and Werner Reinhart, Webern attended three Swiss concerts, his last trips outside the Reich.[295] In 1940, Erich Schmid conducted Op. 1 in Winterthur; soprano Marguerite Gradmann-Lüscher sang Op. 4 and most of Op. 12 (not No. 3) at the Musik-Akademie der Stadt Basel, Schmid accompanying. In Feb. 1943, Scherchen gave the world premiere of Op. 30 at the Winterthur Stadthaus. Webern intimated to Willi Reich that he might immigrate there, joking (Oct. 1939) "Anything of the sort did seem quite out of the question for me!"[296] But Webern failed to find employment, even as a formality, likely due to anti-German sentiment in the context of Swiss neutrality and refugee laws.[297]

In the Reich, he met with former Society violist Othmar Steinbauer about a formal teaching role in Vienna in early 1940, but nothing materialized.[298] He lectured at the homes of Erwin Ratz and Carl Prohaska's widow Margaret (1940–1942).[299] Many private pupils came to him between 1940 and 1943, even from afar, among them briefly Hartmann.[300] Hartmann, who opposed the Nazis, remembered that Webern counseled him to respect authority, at least publicly, for the sake of order.[268]

Wartime hopes and reality

[edit]Sharing in wartime public sentiment at the height of Hitler's popularity (spring 1940), Webern expressed high hopes, crediting him as "unique" and "singular"[bh] for "the new state for which the seed was laid twenty years ago". These were patriotic letters to Joseph Hueber, an active soldier, baritone, close friend, and mountaineering companion who often sent Webern gifts.[301] Indeed, Hueber had just sent Webern Mein Kampf.[bi]

Unaware of Stefan George's aversion to the Nazis, Webern reread Das neue Reich and marveled suggestively at the wartime leader envisioned therein, but "I am not taking a position!" he wrote active soldier, singer, and onetime Social Democrat, Hans Humpelstetter.[303] For Johnson, "Webern's own image of a neue Reich was never of this world; if his politics were ultimately complicitous it was largely because his utopian apoliticism played so easily into ... the status quo."[304]

By Aug. 1940, Webern depended financially on his children.[305] He sought wartime emergency relief funds from Künstlerhilfe Wien and the Reichsmusikkammer Künstlerdank (1940–1944), which he received despite indicating non-membership in the Nazi Party on an application.[306] Whether Webern ever joined the party was unknown.[307][bj] This represented his only income after 1942.[310] He nearly exhausted his savings by 1944.[310]

His 1943–1945 letters were strewn with references to bombings, death, destruction, privation, and the disintegration of local order, but several grandchildren were born.[311] In Dec. 1943, aged 60, he wrote from a barrack that he was working 6 am–5 pm as an air-raid protection police officer, conscripted into the war effort.[311] He corresponded with Willi Reich about IGNM-Sektion Basel's concert marking his sixtieth, in which Paul Baumgartner played Op. 27, Walter Kägi Op. 7, and August Wenzinger Op. 11. Gradmann-Lüscher sang both Opp. 3 and the world premiere of 23.[312] For Schoenberg's 70th birthday (1944), Webern asked Reich to convey "my most heartfelt remembrances, ... longing! ... hopes for a happy future!"[313] In Feb. 1945, Webern's only son Peter, intermittently conscripted since 1940,[314] was killed in an air attack; airstrike sirens interrupted the family's mourning at the funeral.[315]

Refuge and death in Mittersill

[edit]

The Weberns assisted Schoenberg's first son Görgi during the war; with the Red Army's April 1945 arrival imminent, they gave him their Mödling apartment, the property and childhood home of Webern's son-in-law Benno Mattl.[bk] Görgi later told Krasner that Webern "felt he'd betrayed his best friends."[317] The Weberns fled west, resorting to traveling partly on foot to Mittersill to rejoin their family of "17 persons pressed together in the smallest possible space".[318]

On the night of 15 Sept. 1945, Webern was outside smoking when he was shot and killed by a US soldier in an apparent accident.[319] He had been following Thomas Mann's work, which the Nazis had burned, noting in 1944 that Mann had finished Joseph and His Brothers.[320] In his last notebook entry, Webern quoted Rainer Maria Rilke: "Who speaks of victory? To endure is everything."[321][bl]

Webern's wife Minna suffered final years of grief, poverty, and loneliness as friends and family continued emigrating. She wished Webern lived to see more success.[324] With the abolition of Entartete Kunst policies, Alfred Schlee solicited her for hidden manuscripts; thus Opp. 17, 24–25, and 29–31 were published.[324] She worked to get Webern's 1907 Piano Quintet published via Kurt List.[324]

In 1947 she wrote Diez, now in the US, that by 1945 Webern was "firmly resolved to go to England".[324] Likewise, in 1946 she wrote DJ Bach in London: "How difficult the last eight years had been for him. ... [H]e had only the one wish: to flee from this country. But one was caught, without a will of one's own. ... It was close to the limit of endurance what we had to suffer."[324] Minna died in 1949.[324]

Music

[edit]Tell me, can one at all denote thinking and feeling as things entirely separable? I cannot imagine a sublime intellect without the ardor of emotion.

Webern wrote to Schoenberg (June 1910).[325] Theodor Adorno described Webern as "propound[ing] musical expressionism in its strictest sense, ... to such a point that it reverts of its own weight to a new objectivity".[326]

Webern's music was generally concise, organic, and parsimonious,[bm] with very small motifs, palindromes, and parameterization on both the micro- and macro-scale.[332] His idiosyncratic approach reflected affinities with Schoenberg, Mahler,[bn] Guido Adler and early music; interest in esotericism and Naturphilosophie; and thorough perfectionism.[bo] He engaged with the work of Goethe, Bach,[bp] and the Franco-Flemish School in addition to that of Wolf, Brahms,[bq] Wagner, Liszt, Schumann, Beethoven, Schubert ("so genuinely Viennese"), and Mozart.[347][br] Stylistic shifts were not neatly coterminous with gradually developed technical devices, particularly in the case of his mid-period Lieder.[bs]

His music was also characteristically linear and song-like.[355] Much of it (and Berg's[356] and Schoenberg's)[357] was for singing.[40][bt] Johnson described the song-like gestures of Op. 11/i.[360] In Webern's mid-period Lieder, some heard instrumentalizing of the voice[361] (often in relation to the clarinet)[362] representing yet some continuity with bel canto.[363][bu] Lukas Näf described one of Webern's signature hairpins (on the Op. 21/i mm. 8–9 bass clarinet tenuto note) as a messa di voce requiring some rubato to execute faithfully.[365][bv] Adventurous textures and timbres, and melodies of wide leaps and sometimes extreme ranges and registers were typical.[367]

For Johnson, Webern's rubato compressed Mahler's "'surging and ebbing'" tempi; this and Webern's dynamics indicated a "vestigial lyrical subjectivity."[368] Webern often set carefully chosen lyric poetry.[369] He related his music not only to nostalgia for the lost family and home of his youth, but also to his Alpinism and fascination with plant aromatics and morphology.[370] He was compared to Mahler in his orchestration and semantic preoccupations (e.g., memory, landscapes, nature, loss, often Catholic mysticism).[371] In Jone, who he met with her husband Humplik via the Hagenbund, Webern found a lyricist who shared his esoteric, natural, and spiritual interests. She provided texts for his late vocal works.[372]

Webern's and Schoenberg's music distinctively prioritized minor seconds, major sevenths, and minor ninths[bw] as noted in 1934 by microtonalist Alois Hába.[373] The Kholopov siblings noted the semitone's unifying role by axial inversional symmetry and octave equivalence as interval class 1 (ic1), approaching Allen Forte's generalized pitch-class set analysis.[374] Webern's consistent use of ic1 in cells and sets, often expressed as a wide interval musically,[375][bx] was well noted.[by] Symmetric pitch-interval practices varied in rigor and use by others (e.g., Berg, Schoenberg, Bartók, Debussy, Stravinsky; more nascently Mahler, Brahms, Bruckner,[bz] Liszt, Wagner). Berg and Webern took symmetric approaches to elements of music beyond pitch. Webern later linked pitches and other parameters in schemes (e.g., fixed or "frozen" register).[380]

Relatively few of Webern's works were published in his lifetime. Amid fascism and Emil Hertzka's passing, this included late as well as early works (in addition to others without opus numbers). His rediscovery prompted many publications, but some early works were unknown until after the work of the Moldenhauers well into the 1980s,[381] obscuring formative facets of his musical identity.[382] Thus when Boulez first oversaw a project to record Webern's music, the results fit on three CDs and the second time, six.[383][ca] A historical edition of his music has remained in progress.

1899–1908: Formative juvenilia and emergence from study

[edit]Webern published little juvenilia; like Brahms, he was meticulous and self-conscious, revising extensively.[385] His earliest works were mostly Lieder on works of Richard Dehmel, Gustav Falke, and Theodor Storm.[386] He set seven Ferdinand Avenarius poems on the "changing moods" of life and nature (1899–1904).[387] Schubert, Schumann, and Wolf were important models. With its brief, potent expressivity and utopianization of the natural world, the (German) Romantic Lied had a lasting influence on Webern's musical aesthetic.[388] He never abandoned its lyricism, intimacy, and wistful or nostalgic topics, though his music became more abstract, idealized, and introverted.[386]

Webern memorialized the Preglhof in a diary poem "An der Preglhof" and in the tone poem Im Sommerwind (1904), both after Bruno Wille's idyll. In Webern's Sommerwind, Derrick Puffett found affinities with Strauss's Alpensinfonie, Charpentier's Louise, and Delius's Paris.

At the Pregholf in summer 1905, Webern wrote his tripartite, single-movement string quartet in a highly modified sonata form, likely responding to Schoenberg's Op. 7.[389] He quoted Jakob Böhme in the preface[390] and mentioned the panels[cb] of Segantini's Trittico della natura[cc] as "Werden–Sein–Vergehen"[cd] in sketches.[391] Sebastian Wedler argued that this quartet bore the influence of Richard Strauss's Also Sprach Zarathustra in its germinal three-note motive, opening fugato of its third (development) section, and Nietzschean reading (via eternal recurrence) of Segantini's triptych.[392] In its opening harmonies, Allen Forte and Heinz-Klaus Metzger noted Webern's anticipation of Schoenberg's atonality in Op. 10.[393]

In 1906, Schoenberg assigned Webern Bach chorales to harmonize and figure; Webern completed eighteen in a highly chromatic idiom.[394] Then the Passacaglia, Op. 1 (1908) was his graduation piece, and the Op. 2 choral canons soon followed. The passacaglia's chromatic harmonic language and less conventional orchestration distinguished it from prior works; its form foreshadowed those of his later works.[395] Conducting the 1911 Danzig premiere of Op. 1 at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Schützenhaus, he paired it with Debussy's 1894 Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune, Ludwig Thuille's 1896 Romantische Ouvertüre, and Mahler's 1901–1904 Kindertotenlieder in a poorly attended Moderner Abend[ce] concert. The Danziger Zeitung critic derided Op. 1 as an "insane experiment".[396]

In 1908 Webern also began an opera on Maeterlinck's Alladine et Palomides, of which only unfinished sketches remained,[397] and in 1912 he wrote Berg that he had finished one or more scenes for another planned but unrealized opera, Die sieben Prinzessinnen, on Maeterlinck's Les Sept Princesses.[398] He had been an opera enthusiast from his student days.[399] Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande enraptured him twice in Dec. 1908 Berlin and again in 1911 Vienna.[400] As a vocal coach and opera conductor, he knew the repertoire "perfectly ... every cut, ... unmarked cadenza, and in the comic operas every theatrical joke".[401] He "adored" Mozart's Il Seraglio and revered Strauss, predicting Salome would last. When in high spirits, Webern would sing bits of Lortzing's Zar und Zimmermann, a personal favorite. He expressed interest (to Max Deutsch) in writing an opera pending a good text and adequate time; in 1930, he asked Jone for "opera texts, or rather dramatic texts", planning cantatas instead.[402]

1908–1914: Atonality and aphorisms

[edit]Webern's music, like Schoenberg's, was freely atonal after Op. 2. Some of their and Berg's music from this time was published in Der Blaue Reiter.[404] Schoenberg and Webern were so mutually influential, the former later joked, "I haven't the slightest idea who I am".[405] In Op. 5/iii, Webern borrowed from Schoenberg's Op. 10/ii. In Op. 5/iv, he borrowed from Schoenberg's Op. 10/iv setting of "Ich fühle luft von anderen planeten".[406][cf]

The first of Webern's innovative and increasingly extremely aphoristic Opp. 5–11 (1909–1914) radically influenced Schoenberg's Opp. 11/iii[cg] and 16–17 (and Berg's Opp. 4–5).[408] Here, Martin Zenck considered, Webern did not seek "the new ... in [music of] the past but in the future".[409] In writing the Op. 9 bagatelles, Webern reflected in 1932, "I had the feeling that when the twelve notes had all been played the piece was over."[410] "[H]aving freed music from the shackles of tonality," Schoenberg wrote, he and his pupils believed "music could renounce motivic features".[411] This "intuitive aesthetic" arguably proved to be aspirational insofar as motives persisted in their music.[412]

Two enduring topics emerged in Webern's work: familial (especially maternal) loss and memory, often involving some religious experience; and abstracted landscapes idealized as spiritual, even pantheistic, Heimat (e.g., the Preglhof, the Eastern Alps).[413] Webern explored these ideas explicitly in his stage play Tot (Dead, Oct. 1913), which comprises six tableaux vivants set in the Alps, over the course of which a mother and father reflect on and come to terms with the loss of their son.[414][ch] He drew so heavily from Swedenborg's theological doctrine of correspondences, quoting from Vera Christiana Religio at length, that Schoenberg considered the play unoriginal; Webern sublimated its concerns into his music, particularly Op. 6.[416] Confiding in Berg and Schoenberg, Webern told the latter some about the programmatic narrative for that music in Jan. 1913, as Schoenberg prepared to premiere it at what would become the Skandalkonzert that March:[417]

The first piece is to express my frame of mind ... already sensing the disaster, yet ... maintaining the hope that I would find my mother still alive. It was a beautiful day—for a minute I believed ... nothing had happened. Only during the train ride to Carinthia ... did I learn the truth. The third piece conveys ... the fragrance of the Erica, which I gathered ... in the forest ... and ... laid on the bier.[ci] The fourth piece I later entitled marcia funebre. Even today I do not understand my feelings as I walked behind the coffin to the cemetery. ... The evening after ... was miraculous. With my wife I went once again to the cemetery .... I had the feeling of my mother's ... presence.

As Webern's music took on the character of such static dramaticovisual scenes, his pieces frequently culminated in the accumulation and amalgamation (often the developing variation) of compositional material. Fragmented melodies frequently began and ended on weak beats, settled into or emerged from ostinati, and were dynamically and texturally faded, mixed, or contrasted.[419] Tonality became less directional, functional, or narrative than tenuous, spatial, or symbolic as fit Webern's topics and literary settings. Stein thought that "his compositions should be understood as musical visions".[cj] Oliver Korte traced Webern's Klangfelder[ck] to Mahler's "suspensions".[cl]

Expanding on Mahler's orchestration, Webern linked colorful, novel, fragile, and intimate sounds, often nearly silent at ppp, to lyrical topics: solo violin to female voice; closed or open voicings, sometimes sul ponticello, to dark or light respectively; compressed range to absence, emptiness, or loneliness; registral expansion to fulfillment, (spiritual) presence, or transcendence;[cm] celesta, harp, and glockenspiel to the celestial or ethereal; and trumpet, harp, and string harmonics to angels or heaven.[421][cn]

With elements of Kabarett,[co] neoclassicism,[cp] and ironic Romanticism[cq] in Pierrot lunaire, Op. 21 (1912), Schoenberg began[cr] to distance himself from Webern's and latterly Berg's aphoristic expressionism, which provoked the Skandalkonzert. Alma recalled Schoenberg telling her and Franz Werfel "how much he was suffering under the dangerous influence of Webern", drawing on "all his strength to extricate himself from it".[422]

1914–1924: Mid-period Lieder

[edit]During and after World War I (1914–1926) Webern worked on some fifty-six songs.[425] He finished thirty-two, ordered into sets (in ways that do not always align with their chronology) as Opp. 12–19.[425] Schoenberg's recent vocal music had been motivated by the idea that "absolute purity" in composition couldn't be sustained,[426] and Webern took Schoenberg's advice to write songs as a means of composing something more substantial than aphorisms, often making earnest settings of folk, lyric, or spiritual texts.[427] The first of these mid-period Lieder was an unfinished setting of a passage ("In einer lichten Rose ...") from Dante's Paradiso, Canto XXXI.[428]

By comparison to melodic "atomization" in Op. 11, Walter Kolneder noted relatively "long arcs" melodic writing in Op. 12[429] and polyphonic part writing to "control the ... expression" in Opp. 12–16 more generally.[430] "How much I owe to your Pierrot", Webern told Schoenberg after setting Trakl's "Abendland III" (Op. 14/iv),[431] in which, distinctly, there was no silence until a pause at the concluding gesture. The contrapuntal procedures and nonstandard ensemble of Pierrot are both evident in Webern's Opp. 14–16.[432]

Schoenberg "yearn[ed] for a style for large forms ... to give personal things an objective, general form."[ct] Berg, Webern, and he had indulged their shared interest in Swedenborgian mysticism and Theosophy since 1906, reading Balzac's Louis Lambert and Séraphîta and Strindberg's Till Damaskus and Jacob lutte. Gabriel, protagonist of Schoenberg's semi-autobiographical Die Jakobsleiter (1914–1922, rev. 1944)[cu] described a journey: "whether right, whether left, forwards or backwards, uphill or down – one must keep on going without asking what lies ahead or behind",[cv] which Webern interpreted as a conceptual metaphor for (twelve-tone) pitch space.[439] Schoenberg later reflected on "how enthusiastic we were about this."[cw]

On the journey to composition with twelve tones, Webern revised many of his mid-period Lieder in the years after their apparent composition but before publication, increasingly prioritizing clarity of pitch relations, even against timbral effects, as Anne C. Shreffler[441] and Felix Meyer described. His and Schoenberg's music had long been marked by its contrapuntal rigor, formal schemes, systematic pitch organization, and rich motivic design, all of which they found in the music of Brahms before them.[442] Webern had written music preoccupied with the idea of dodecaphony since at least the total chromaticism of his Op. 9 bagatelles (1911)[443] and Op. 11 cello pieces (1914).[444][cx]

There are twelve-tone sets with repeated notes at the start of Op. 12/i and in some bars of Op. 12/iv, in addition to many ten- and eleven-tone sets throughout Op. 12.[446] Webern wrote to Jalowetz in 1922 about Schoenberg's lectures on "a new type of motivic work", one that "unfolds the entire development of, if I may say so, our technique (harmony, etc)".[447] It was "almost everything that has occupied me for about ten years", Webern continued.[448] He regarded Schoenberg's transformation of twelve-tone rows as the "solution" to their compositional concerns.[449] In Op. 15/iv (1922), Webern first used a tone row (in the voice's opening twelve notes), charted the four basic row forms, and integrated tri- and tetrachords into the harmonic and melodic texture.[450] He systematically used twelve-tone technique for the first time in Op. 16/iv–v (1924).[451]

1924–1945: Formal coherence and expansion

[edit]With Schoenberg leaving Mödling in 1925 and this compositional approach at his disposal, Webern obtained more artistic autonomy and aspired to write in larger forms, expanding on the extreme concentration of expression and material in his earlier music.[454] Until the Kinderstück for piano (1924, intended as one of a set), Klavierstück (1925), and Satz for string trio (1925), Webern had finished nothing but Lieder since a 1914 cello sonata.[455][cy] The 1926–1927 String Trio, Op. 20, was his first large-scale non-vocal work in more than a decade. For its 1927 publication, Webern helped Stein write an introduction emphasizing continuity with tradition:[457]

The principle of developing a movement by variation of motives and themes is the same as with the classical masters ... [only] varied more radically here ... . One 'tone series' furnishes the basic material ... . The parts are composed in a mosaic-like manner ...

Schoenberg exploited combinatorial properties of particular tone rows,[458] but Webern focused on prior aspects of a row's internal organization. He exploited small, invariant pitch subsets (or partitions) symmetrically derived via inversion, retrograde, or both (retrograde inversion). He understood his compositional (and precompositional) work with reference to ideas about growth, morphology, and unity that he found represented in Goethe's Urpflanze and in Goethean science more generally.[459][cz]

Webern's large-scale, non-vocal music in more traditional genres,[da] written from 1926 to 1940, has been celebrated as his most rigorous and abstract music.[461] Yet he always wrote his music and tried his new compositional procedures with concern for (or at least some latent reference to) expressivity and representation.[462][db] In sketches for his Op. 22 quartet, Webern conceived of his themes in programmatic association with his experiences—as an "outlook into the highest region" or a "coolness of early spring (Anninger,[dc] first flora, primroses, anemones, pasqueflowers)", for example.[467] Studying his compositional materials and sketches, Bailey Puffett wrote,[468]

... [Webern] seems perhaps not ... a prodigy whose music was the result of reasoned calculations [but a composer] who used his row tables as Stravinsky used his piano, to reveal wonderful surprises ... [like] he found on his walks in the Alps.

While writing the Concerto for Nine Instruments, Op. 24, Webern was inspired by the Sator square, which is like a twelve-tone matrix.[469] He concluded his Weg zur Neuen Musik with this magic square.

In Webern's late cantatas and songs,[dd] George Rochberg observed, "the principles of 'the structural spatial dimension' ... join[ed] forces with lyrico-dramatic demands".[470] Specifically in his cantatas, Bailey Puffett wrote, Webern synthesized the rigorous style of his mature instrumental works with the word painting of his Lieder on an orchestral scale.[471] Webern qualified the apparent connection between his cantatas and Bach's as general and referred to connections between the second cantata and the music of the Franco-Flemish School.[472] His textures became somewhat denser yet more homophonic at the surface through nonetheless contrapuntal polyphonic means.[473] In Op. 31/i he alternated lines and points, culminating twice[de] in twelve-note simultaneities.[474]

At his death he left sketches for the movement of an apparent third cantata (1944–1945), first planned as a concerto, setting "Das Sonnenlicht spricht" from Jone's Lumen cycle.[475]

Arrangements and orchestrations

[edit]In his youth (1903), Webern orchestrated five or more Schubert Lieder for an appropriately Schubertian orchestra (strings and pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns). Among these were "Der Vollmond Strahlt auf Bergeshöhn" (the Romanze from Rosamunde), "Tränenregen" (from Die schöne Müllerin), "Der Wegweiser" (from Winterreise), "Du bist die Ruh", and "Ihr Bild".[476]

After attending Hugo Wolf's funeral and memorial concert (1903), he arranged three Lieder for a larger orchestra, adding brass, harp, and percussion to the Schubertian orchestra. He chose "Lebe wohl", "Der Knabe und das Immlein", and "Denk es, o Seele", of which only the latter was finished or wholly survived.[477]

For Schoenberg's Society for Private Musical Performances in 1921, Webern arranged, among other music,[5] the 1888 Schatz-Walzer (Treasure Waltz) of Johann Strauss II's Der Zigeunerbaron (The Gypsy Baron) for string quartet, harmonium, and piano.

In 1924 Webern arranged Liszt's Arbeiterchor (Workers' Chorus, c. 1847–1848)[478] for bass solo, mixed chorus, and large orchestra; thus Liszt's work was finally premièred[df] when Webern conducted the first full-length concert of the Austrian Association of Workers Choir (13 and 14 March 1925). A review in the Wiener Zeitung (28 March 1925) read "neu in jedem Sinne, frisch, unverbraucht, durch ihn zieht die Jugend, die Freude" ("new in every respect, fresh, vital, pervaded by youth and joy").[183] The text (in English translation) read in part: "Let us have the adorned spades and scoops,/Come along all, who wield a sword or pen,/Come here ye, industrious, brave and strong/All who create things great or small."

In orchestrating the six-voice ricercar from Bach's Musical Offering, Webern timbrally defined the internal organization (or latent subsets) of the Bach's subject.[480] Joseph N. Straus argued that Webern (and other modernists) effectively recomposed earlier music, "projecting motivic density" onto tradition.[481] After more conservatively orchestrating two of Schubert's 1824 Six German Dances on UE commission in 1931, he wrote Schoenberg:

I took pains to remain on the solid ground of classical ideas of instrumentation, yet to place them into the service of our idea, i.e., as a means toward the greatest possible clarification of thought and context.[dg]

Reception, influence, and legacy

[edit]Webern's music was generally considered difficult by performers and inaccessible by listeners alike.[483] "To the limited extent that it was regarded", Milton Babbitt observed, it represented "the ultimate in hermetic, specialized, and idiosyncratic composition".[484]

Composers and performers first tended to take Webern's work, with its residual post-Romanticism and initial expressionism, in mostly formalist directions with a certain literalism, departing from Webern's own practices and preferences in extrapolating from elements of his late style. This became known as post-Webernism.[485] A richer, more historically informed understanding of Webern's music and his performance practice began to emerge in the latter half of the 20th century as scholars, especially the Moldenhauers, sought and archived sketches, letters, lectures, recordings, and other articles of Webern's (and others') estates.[dh]

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, Webern's marginalization under Gleichschaltung was appreciated, but his pan-Germanism, politics, and social attitudes (especially regarding antisemitism) were not as known or often mooted.[486] For many, like Stravinsky, Webern never compromised his artistic identity and values, but for others the matter was less simple.[di]

Performance practice

[edit]Eric Simon ... related ... : 'Webern was obviously upset by Klemperer's sober time-beating. ... [T]o the concert master [he] said: "... the phrase there ... must be played Tiiiiiiiiiii-aaaaaaaaa." Klemperer, overhearing ... said sarcastically: "... [N]ow you probably know exactly how you have to play the passage!"' Peter Stadlen ... [described Webern]'s reaction after the performance: ... '"A high note, a low note, a note in the middle—like the music of a madman!"'

The Moldenhauers detailed Webern's reaction to Otto Klemperer's 1936 Vienna performance of his Symphony (1928), Op. 21, which Webern played on piano for Klemperer "with ... intensity and fanaticism ... passionately".[487]

Webern notated articulations, dynamics, tempo rubato, and other musical expressions, coaching performers to adhere to these instructions but urging them to maximize expressivity through musical phrasing.[487][dj] This was supported by personal accounts, correspondence, and extant recordings of Schubert's Deutsche Tänze (arr. Webern) and Berg's Violin Concerto under Webern's direction. Ian Pace considered Peter Stadlen's account of Webern's coaching for Op. 27 as indicating Webern's "desire for an extremely flexible, highly diaphanous, and almost expressively overloaded approach".[489][dk]

This aspect of Webern's work was often overlooked in his immediate post-war reception,[491] which was roughly coterminous with the early music revival. Stravinsky engaged with Webern and Renaissance music in his later music; his amanuensis Craft performed Webern as well as Monteverdi, Schütz, Gabrieli, and Tallis.[492] Many musicians performed "music that is at the same time old and new", as Nicholas Cook and Anthony Pople glossed it and as Richard Taruskin addressed. J. Peter Burkholder noted early and new music audience overlap.[493]

Felix Galimir of the Galimir Quartet told The New York Times (1981): "Berg asked for enormous correctness in the performance of his music. But the moment this was achieved, he asked for a very Romanticized treatment. Webern, you know, was also terribly Romantic—as a person, and when he conducted. Everything was almost over-sentimentalized. It was entirely different from what we have been led to believe today. His music should be played very freely, very emotionally."[494]

Contemporaries

[edit]Artists

[edit]Many artists portrayed Webern (often from life) in their work. Kokoschka (1912), Schiele (1917 and 1918), B. F. Dolbin (1920 and 1924), and Rederer (1934) made drawings of him. Oppenheimer (1908), Kokoschka (1914), and Tom von Dreger (1934) painted him. Stumpp made two lithographs of him (1927). Humplik twice sculpted him (1927 and 1928). Jone variously portrayed him (1943 lithograph, several posthumous drawings, 1945 oil painting). Rederer made a large woodcut of him (1964).[495]

Musicians

[edit]Schoenberg admired Webern's concision, writing in the foreword to Op. 9 upon its 1924 publication: "to express a novel in a single gesture, joy in a single breath—such concentration can only be present in proportion to the absence of self-indulgence".[496] But Berg joked about Webern's brevity. Hendrik Andriessen found Webern's music "pitiful" in this regard.[497] In their second (1925) Abbruch[dl] self-parody, Anbruch[dm] editors jested that "Webern's" (Mahler's) "extensive" Symphony of a Thousand had to be abbreviated.[dn]

Felix Khuner remembered Webern was "just as revolutionary" as Schoenberg.[498] In 1927, Hans Mersmann wrote that "Webern's music shows the frontiers and ... limits of a development which tried to outgrow Schoenberg's work."[499]

Identifying with Webern as a "solitary soul" amid 1940s wartime fascism,[500] Dallapiccola independently and somewhat singularly[do] found inspiration especially in Webern's lesser-known mid-period Lieder, blending its ethereal qualities and Viennese expressionism with bel canto.[501] Stunned by Webern's Op. 24 at its 1935 ISCM festival world première under Jalowetz in Prague, Dallapiccola's impression was of unsurpassable "aesthetic and stylistic unity".[502] He dedicated Sex carmina alcaei[dp] "with humility and devotion" to Webern, who he met in 1942 through Schlee, coming away surprised at Webern's emphasis on "our great Central European tradition."[503] Dallapiccola's 1953 Goethe-lieder especially recall Webern's Op. 16 in style.[504]

In 1947, Schoenberg remembered and stood firm with Berg and Webern despite rumors of the latter's having "fallen into the Nazi trap":[dq] "... [F]orget all that might have ... divided us. For there remains for our future what could only have begun to be realized posthumously: One will have to consider us three—Berg, Schoenberg, and Webern—as a unity, a oneness, because we believed in ideals ... with intensity and selfless devotion; nor would we ever have been deterred from them, even if those who tried might have succeeded in confounding us."[dr] For Krasner this put "'Vienna's Three Modern Classicists' into historical perspective". He summarized it as "what bound us together was our idealism."[505]

1947–1950s: (Re)discovery and post-Webernism

[edit]Webern's death should be a day of mourning for any receptive musician. We must hail ... this great ... a real hero. Doomed to ... failure in a deaf world of ignorance and indifference he ... kept on cutting ... dazzling diamonds, the mines of which he had ... perfect knowledge.

After World War II, there was unprecedented engagement with Webern's music. It came to represent a universally or generally valid, systematic, and compellingly logical model of new composition, especially at the Darmstädter Ferienkurse.[510] René Leibowitz performed, promulgated, and published Schoenberg et son école;[511] Adorno,[512] Herbert Eimert, Scherchen,[513] and others contributed. Composers and students[dt] listened in a quasi-religious trance to Peter Stadlen's 1948 Op. 27 performance.[514]

Webern's gradual innovations in schematic organization of pitch, rhythm, register, timbre, dynamics, articulation, and melodic contour; his generalization of imitative techniques such as canon and fugue; and his inclination toward athematicism, abstraction, and lyricism variously informed and oriented European and Canadian, typically serial or avant-garde composers (e.g., Messiaen, Boulez, Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Pousseur, Ligeti, Sylvano Bussotti, Bruno Maderna, Bernd Alois Zimmermann, Barbara Pentland).[515] Eimert and Stockhausen devoted a special issue of die Reihe to Webern's œuvre in 1955. UE published his lectures in 1960.[516]

In the US, Babbitt[517] and initially Rochberg[518] found more in Schoenberg's twelve-tone practice. Elliott Carter's and Aaron Copland's critical ambivalence was marked by a certain enthusiasm and fascination nonetheless.[519] Craft fruitfully reintroduced Stravinsky to Webern's music, without which Stravinsky's late works would have taken different shape. Stravinsky staked his contract with Columbia Records to see Webern's then known music first both recorded and widely distributed.[520] Stravinsky lauded Webern's "not yet canonized art" in 1959.[521]

Among the New York School, John Cage and Morton Feldman first met in Carnegie Hall's lobby, ecstatic after a performance of Op. 21 by Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic. They cited the effect of its sound on their music.[522] They later sung the praises of Christian Wolff as "our Webern".