Vivisection

Vivisection (from Latin vivus 'alive' and sectio 'cutting') is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative[1] catch-all term for experimentation on live animals[2][3][4] by organizations opposed to animal experimentation,[5] but the term is rarely used by practicing scientists.[3][6] Human vivisection, such as live organ harvesting, has been perpetrated as a form of torture.[7][8]

Animal vivisection

[edit]

Regulations and laws

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Animal rights |

|---|

Research requiring vivisection techniques that cannot be met through other means is often subject to an external ethics review in conception and implementation, and in many jurisdictions use of anesthesia is legally mandated for any surgery likely to cause pain to any vertebrate.[9]

In the United States, the Animal Welfare Act explicitly requires that any procedure that may cause pain use "tranquilizers, analgesics, and anesthetics" with exceptions when "scientifically necessary".[10] The act does not define "scientific necessity" or regulate specific scientific procedures,[11] but approval or rejection of individual techniques in each federally funded lab is determined on a case-by-case basis by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which contains at least one veterinarian, one scientist, one non-scientist, and one other individual from outside the university.[12]

In the United Kingdom, any experiment involving vivisection must be licensed by the Home Secretary. The Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 "expressly directs that, in determining whether to grant a licence for an experimental project, 'the Secretary of State shall weigh the likely adverse effects on the animals concerned against the benefit likely to accrue.'"[13]

In Australia, the Code of Practice "requires that all experiments must be approved by an Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee" that includes a "person with an interest in animal welfare who is not employed by the institution conducting the experiment, and an additional independent person not involved in animal experimentation."[14]

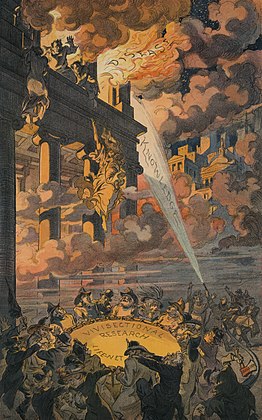

Anti-vivisection movement

[edit]Anti-vivisectionists have played roles in the emergence of the animal welfare and animal rights movements, arguing that animals and humans have the same natural rights as living creatures, and that it is inherently immoral to inflict pain or injury on another living creature, regardless of the purpose or potential benefit to mankind.[5][15]

19th century

[edit]At the turn of the 19th century, medicine was undergoing a transformation. The emergence of hospitals and the development of more advanced medical tools such as the stethoscope are but a few of the changes in the medical field.[16] There was also an increased recognition that medical practices needed to be improved, as many of the current therapeutics were based on unproven, traditional theories that may or may not have helped the patient recover. The demand for more effective treatment shifted emphasis to research with the goal of understanding disease mechanisms and anatomy.[16] This shift had a few effects, one of which was the rise in patient experimentation, leading to some moral questions about what was acceptable in clinical trials and what was not. An easy solution to the moral problem was to use animals in vivisection experiments, so as not to endanger human patients. This, however, had its own set of moral obstacles, leading to the anti-vivisection movement.[16]

François Magendie (1783–1855)

[edit]

One polarizing figure in the anti-vivisection movement was François Magendie. Magendie was a physiologist at the Académie Royale de Médecine in France, established in the first half of the 19th century.[16] Magendie made several groundbreaking medical discoveries, but was far more aggressive than some of his contemporaries in the use of animal experimentation. For example, the discovery of the different functionalities of dorsal and ventral spinal nerve roots was achieved by both Magendie, as well as a Scottish anatomist named Charles Bell. Bell used an unconscious rabbit because of "the protracted cruelty of the dissection", which caused him to miss that the dorsal roots were also responsible for sensory information. Magendie, on the other hand, used conscious, six-week-old puppies for his own experiments.[16][17] While Magendie's approach would today be considered an abuse of animal rights, both Bell and Magendie used the same rationalization for vivisection: the cost of animal experimentation being worth it for the benefit of humanity.[17]

Many[who?] viewed Magendie's work as cruel and unnecessarily torturous. One note is that Magendie carried out many of his experiments before the advent of anesthesia, but even after ether was discovered it was not used in any of his experiments or classes.[16] Even during the period before anesthesia, other physiologists[who?] expressed their disgust with how he conducted his work. One such visiting American physiologist describes the animals as "victims" and the apparent sadism that Magendie displayed when teaching his classes.[verify] Magendie's experiments were cited in the drafting of the British Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 and Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act 1822, otherwise known as Martin's Act.[16] The latter bill's namesake, Irish MP and well known anti-cruelty campaigner Richard Martin, called Magendie a "disgrace to Society" and his public vivisections "anatomical theatres" following a prolonged dissection of a greyhound which attracted wide public comment.[18] Magendie faced widespread opposition in British society, among the general public but also his contemporaries, including William Sharpey who described his experiments aside from cruel as "purposeless" and "without sufficient object", a feeling he claimed was shared among other physiologists.[19]

David Ferrier and the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876

[edit]

The Cruelty to Animals Act, 1876 in Britain determined that one could only conduct vivisection on animals with the appropriate license from the state, and that the work the physiologist was doing had to be original and absolutely necessary.[20] The stage was set for such legislation by physiologist David Ferrier. Ferrier was a pioneer in understanding the brain and used animals to show that certain locales of the brain corresponded to bodily movement elsewhere in the body in 1873. He put these animals to sleep, and caused them to move unconsciously with a probe. Ferrier was successful, but many decried his use of animals in his experiments. Some of these arguments came from a religious standpoint. Some were concerned that Ferrier's experiments would separate God from the mind of man in the name of science.[20] Some of the anti-vivisection movement in England had its roots in Evangelicalism and Quakerism. These religions already had a distrust for science, only intensified by the recent publishing of Darwin's Theory of Evolution in 1859.[17]

Neither side was pleased with how the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876 was passed. The scientific community felt as though the government was restricting their ability to compete with the quickly advancing France and Germany with new regulations. The anti-vivisection movement was also unhappy, but because they believed that it was a concession to scientists for allowing vivisection to continue at all.[20] Ferrier would continue to vex the anti-vivisection movement in Britain with his experiments when he had a debate with his German opponent, Friedrich Goltz. They would effectively enter the vivisection arena, with Ferrier presenting a monkey, and Goltz presenting a dog, both of which had already been operated on. Ferrier won the debate, but did not have a license, leading the anti-vivisection movement to sue him in 1881. Ferrier was not found guilty, as his assistant was the one operating, and his assistant did have a license.[20] Ferrier and his practices gained public support, leaving the anti-vivisection movement scrambling. They made the moral argument that given recent developments, scientists would venture into more extreme practices to operating on "the cripple, the mute, the idiot, the convict, the pauper, to enhance the 'interest' of [the physiologist's] experiments".[20]

20th century

[edit]In the early 20th-century the anti-vivisection movement attracted many female supporters associated with women's suffrage.[21] The American Anti-Vivisection Society advocated total abolition of vivisection whilst others such as the American Society for the Regulation of Vivisection wanted better regulation subjected to surveillance, not full prohibition.[21][22] The Research Defence Society made up of an all-male group of physiologists was founded in 1908 to defend vivisection.[23] In the 1920s, anti-vivisectionists exerted significant influence over the editorial decisions of medical journals.[21]

Human vivisection

[edit]It is possible that human vivisection was practised by some Greek anatomists in Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE. Celsus in De Medicina states that Herophilos of Alexandria vivisected some criminals sent by the king. The early Christian writer Tertullian states that Herophilos vivisected at least 600 live prisoners, although the accuracy of this claim is disputed by many historians.[24]

In the 12th century CE, Andalusian Arab Ibn Tufail elaborated on human vivisection in his treatise called Hayy ibn Yaqzan. In an extensive article on the subject, Iranian academic Nadia Maftouni believes him to be among the early supporters of autopsy and vivisection.[25]

Unit 731, a biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army, undertook lethal human experimentation during the period that comprised both the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Second World War (1937–1945). In the Filipino island of Mindanao, Moro Muslim prisoners of war were subjected to various forms of vivisection by the Japanese, in many cases without anesthesia.[8][26]

Nazi human experimentation involved many medical experiments on live subjects, such as vivisections by Josef Mengele,[27] usually without anesthesia.[28]

See also

[edit]- Alternatives to animal testing

- American Anti-Vivisection Society

- Animal testing regulations

- Bionics

- Cruelty to animals

- Dissection

- Experimentation on prisoners, including vivisection

- History of animal testing

- Human subject research

- Intrinsic value (animal ethics)

- Lingchi, an execution method in Imperial China

- New England Anti-Vivisection Society

- Pro-Test

- Speaking of Research

References

[edit]- ^ Donna Yarri (18 August 2005). The Ethics of Animal Experimentation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190292829. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ^ "Operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals". 25 March 2006. Archived from the original on 25 March 2006. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Tansey, E.M. Review of Vivisection in Historical Perspective by Nicholaas A. Rupke Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, book reviews, National Center for Biotechnology Information, p. 226.

- ^ Croce, Pietro. Vivisection or Science? An Investigation into Testing Drugs and Safeguarding Health. Zed Books, 1999, and "About Us" Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine, British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection.

- ^ a b Yarri, Donna. The Ethics of Animal Experimentation: A Critical Analysis and Constructive Christian Proposal Archived 2022-06-20 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 163.

- ^ Paixao, RL; Schramm, FR. Ethics and animal experimentation: what is debated? Ethics and animal experimentation: what is debated? Archived 2011-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro, 2007

- ^ "CHINA: ORGAN PROCUREMENT AND JUDICIAL EXECUTION IN CHINA". www.hrw.org. 1994. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ a b Richard Lloyd Parry (25 February 2007). "Dissect them alive: order not to be disobeyed". Times Online. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Institute for Laboratory Animal Research (1996). Read "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals" at NAP.edu. doi:10.17226/5140. hdl:2027/mdp.39015012532662. ISBN 978-0-309-05377-8. PMID 25121211. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2019 – via www.nap.edu.

- ^

- ^ "US Code, Title 7: CHAPTER 54—TRANSPORTATION, SALE, AND HANDLING OF CERTAIN ANIMALS" (PDF). www.aphis.usda.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "American Association for Laboratory Animal Science". AALAS. Archived from the original on 2 April 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Balls, M., Goldberg, A. M., Fentem, J. H., Broadhead, C. L., Burch, R. L., Festing, M. F., ... & Van Zutphen, B. F. (1995). The three Rs: the way forward: the report and recommendations of ECVAM Workshop 11. Alternatives to laboratory animals: ATLA, 23(6), 838.

- ^ Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation. Avon: New York, 1990, p. 77

- ^ Carroll, Lewis (June 1875). "Some popular fallacies about vivisection". The Fortnightly Review. 17: 847–854. Archived from the original on 9 January 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g Franco, Nuno Henrique (19 March 2013). "Animal Experiments in Biomedical Research: A Historical Perspective". Animals. 3 (1): 238–273. doi:10.3390/ani3010238. ISSN 2076-2615. PMC 4495509. PMID 26487317.

- ^ a b c "A History of Antivivisection from the 1800s to the Present: Part I (mid-1800s to 1914)". the black ewe. 10 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Leffingwell, Albert (1916). An ethical problem: or, Sidelights upon scientific experimentation on man and animals (2nd, revised ed.). London; New York: G. Bell and Sons; C. P. Farrell. OCLC 3145143. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

practices, equally cruel, with which he thought the legislature ought to interfere. There was a Frenchman by the name of Magendie, whom he considered a disgrace to Society. In the course of the last year this man, at one of his anatomical theatres, exhibited a series of experiments so atrocious as almost to shock belief. This M. Magendie got a lady's greyhound. First of all he nailed its front, and then its hind, paws with the bluntest spikes that he could find, giving as reason that the poor beast, in its agony, might tear away from the spikes if they were at all sharp or cutting. He then doubled up its long ears, and nailed them down with similar spikes. (Cries of `Shame!') He then made a gash down the middle of the face, and proceeded to dissect all the nerves on one side of it.... After he had finished these operations, this surgical butcher then turned to the spectators, and said: `I have now finished my operations on one side of this dog's head, and I shall reserve the other side till to-morrow. If the servant takes care of him for the night, I am of the opinion that I shall be able to continue my operations upon him to-morrow with as much satisfaction to us all as I have done to-day; but if not, ALTHOUGH HE MAY HAVE LOST THE VIVACITY HE HAS SHOWN TO-DAY, I shall have the opportunity of cutting him up alive, and showing you the motion of the heart.' Mr. Martin added that he held in his hands the written declarations of Mr. Abernethy, of Sir Everard Home (and of other distinguished medical men), all uniting in condemnation of such excessive and protracted cruelty as had been practised by this Frenchman." {1} Hansard's Parliamentary Reports, February 24, 1825.

- ^ Leffingwell, Albert (1916). An ethical problem: or, Sidelights upon scientific experimentation on man and animals. London; New York: G. Bell and Sons; C.P. Farrell. OCLC 3145143. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

Another witness of Magendie's cruelty was Dr. William Sharpey, LL.D., Fellow of the Royal Society, and for more than thirty years the professor of physiology in University College, London. ... Before the Royal Commission on Vivisection, in 1876, he gave the following account of his personal experience: "When I was a very young man, studying in Paris, I went to the first of a series of lectures which Magendie gave upon experimental physiology; and I was so utterly repelled by what I witnessed that I never went again. In the first place, they were painful (in those days there were no anaesthetics), and sometimes they were severe; and then THEY WERE WITHOUT SUFFICIENT OBJECT. For example, Magendie made incisions into the skin of rabbits and other creatures TO SHOW THAT THE SKIN IS SENSITIVE! Surely all the world knows the skin is sensitive; no experiment is wanted to prove that. Several experiments he made were of a similar character, AND HE PUT THE ANIMALS TO DEATH, FINALLY, IN A VERY PAINFUL WAY.... Some of his experiments excited a strong feeling of abhorrence, not in the public merely, but among physiologists. There was his--I was going to say `famous' experiment; it might rather have been called `INFAMOUS' experiment upon vomiting .... Besides its atrocity, it was really purposeless." [2] Evidence before Royal Commission, 1875, Questions 444, 474.

- ^ a b c d e Finn, Michael A.; Stark, James F. (1 February 2015). "Medical science and the Cruelty to Animals Act 1876: A re-examination of anti-vivisectionism in provincial Britain" (PDF). Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 49: 12–23. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2014.10.007. PMID 25437634. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ a b c Ross, Karen (2014). "Winning Women's Votes: Defending Animal Experimentation and Women's Clubs in New York, 1920–1930". New York History. 95 (1): 26–40. doi:10.1353/nyh.2014.0050.

- ^ Recarte, Claudia Alonso (2014). "The Vivisection Controversy in America" (PDF). Franklin Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 March 2024.

- ^ Bates, A. W. H. (2017). The Research Defence Society: Mobilizing the Medical Profession for Materialist Science in the Early-Twentieth Century. In Anti-Vivisection and the Profession of Medicine in Britain: A Social History. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Tertullian, De Anima 10.

- ^ Maftouni, Nadia (2019). "Concept of sciart in the Andalusian Ibn Tufail". Pensamiento. Revista de Investigación e Información Filosófica. 75 (283 S.Esp): 543–551. doi:10.14422/pen.v75.i283.y2019.031. S2CID 171734089.

- ^ "Unmasking Horror" Archived 2022-08-13 at the Wayback Machine Nicholas D. Kristof (March 17, 1995) New York Times. A special report.; Japan Confronting Gruesome War Atrocity

- ^ Brozan, Nadine (15 November 1982). "OUT OF DEATH, A ZEST FOR LIFE". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- ^ "Dr. Josef Mengele, ruthless Nazi concentration camp doctor – The Crime Library on trutv.com". Crimelibrary.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2010.