Antisemitism

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

| Freedom of religion |

|---|

| Religion portal |

Antisemitism[a] or Jew-hatred[2] is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against, Jews.[3][4][5] This sentiment is a form of racism,[b][6][7] and a person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Primarily, antisemitic tendencies may be motivated by negative sentiment towards Jews as a people or by negative sentiment towards Jews with regard to Judaism. In the former case, usually presented as racial antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by the belief that Jews constitute a distinct race with inherent traits or characteristics that are repulsive or inferior to the preferred traits or characteristics within that person's society.[8] In the latter case, known as religious antisemitism, a person's hostility is driven by their religion's perception of Jews and Judaism, typically encompassing doctrines of supersession that expect or demand Jews to turn away from Judaism and submit to the religion presenting itself as Judaism's successor faith—this is a common theme within the other Abrahamic religions.[9][10] The development of racial and religious antisemitism has historically been encouraged by the concept of anti-Judaism,[11][12] which is distinct from antisemitism itself.[13]

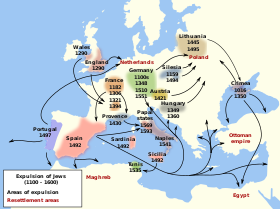

There are various ways in which antisemitism is manifested, ranging in the level of severity of Jewish persecution. On the more subtle end, it consists of expressions of hatred or discrimination against individual Jews and may or may not be accompanied by violence. On the most extreme end, it consists of pogroms or genocide, which may or may not be state-sponsored. Although the term "antisemitism" did not come into common usage until the 19th century, it is also applied to previous and later anti-Jewish incidents. Notable instances of antisemitic persecution include the Rhineland massacres in 1096; the Edict of Expulsion in 1290; the European persecution of Jews during the Black Death, between 1348 and 1351; the massacre of Spanish Jews in 1391, the crackdown of the Spanish Inquisition, and the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492; the Cossack massacres in Ukraine, between 1648 and 1657; various anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire, between 1821 and 1906; the Dreyfus affair, between 1894 and 1906; the Holocaust by Nazi Germany during World War II; and various Soviet anti-Jewish policies. Historically, most of the world's violent antisemitic events have taken place in Christian Europe. However, since the early 20th century, there has been a sharp rise in antisemitic incidents across the Arab world, largely due to the surge in Arab antisemitic conspiracy theories, which have been cultivated to an extent under the aegis of European antisemitic conspiracy theories.[14][15]

In recent times, the idea that there is a variation of antisemitism known as "new antisemitism" has emerged on several occasions. According to this view, since Israel is a Jewish state, expressions of anti-Zionist positions could harbour antisemitic sentiments.[16][17] Natan Sharansky describes the "3D" test to determine the existence of such antisemitism: demonizing Israel, the double standard of criticizing Israel disproportionately to other countries, and delegitimizing Israel's right to exist.[18]

Due to the root word Semite, the term is prone to being invoked as a misnomer by those who incorrectly assert (in an etymological fallacy) that it refers to racist hatred directed at "Semitic people" in spite of the fact that this grouping is an obsolete historical race concept. Likewise, such usage is erroneous; the compound word antisemitismus was first used in print in Germany in 1879[19] as a "scientific-sounding term" for Judenhass (lit. 'Jew-hatred'),[20][21][22][23][24] and it has since been used to refer to anti-Jewish sentiment alone.[20][25][26]

Origin and usage

Etymology

The word "Semitic" was coined by German orientalist August Ludwig von Schlözer in 1781 to designate the Semitic group of languages—Aramaic, Arabic, Hebrew and others—allegedly spoken by the descendants of Biblical figure Sem, son of Noah.[27][28]

The origin of "antisemitic" terminologies is found in the responses of orientalist Moritz Steinschneider to the views of orientalist Ernest Renan. Historian Alex Bein writes: "The compound anti-Semitism appears to have been used first by Steinschneider, who challenged Renan on account of his 'anti-Semitic prejudices' [i.e., his derogation of the "Semites" as a race]."[29] Psychologist Avner Falk similarly writes: "The German word antisemitisch was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907) in the phrase antisemitische Vorurteile (antisemitic prejudices). Steinschneider used this phrase to characterise the French philosopher Ernest Renan's false ideas about how 'Semitic races' were inferior to 'Aryan races'".[30]

Pseudoscientific theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the phrase "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazis.[31] According to Falk, Treitschke uses the term "Semitic" almost synonymously with "Jewish", in contrast to Renan's use of it to refer to a whole range of peoples,[32] based generally on linguistic criteria.[33]

According to philologist Jonathan M. Hess, the term was originally used by its authors to "stress the radical difference between their own 'antisemitism' and earlier forms of antagonism toward Jews and Judaism."[34]

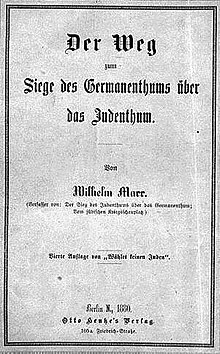

In 1879, German journalist Wilhelm Marr published a pamphlet, Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet (The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective) in which he used the word Semitismus interchangeably with the word Judentum to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "Jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit).[35][36][37] He accused the Jews of a worldwide conspiracy against non-Jews, called for resistance against "this foreign power", and claimed that "there will be absolutely no public office, even the highest one, which the Jews will not have usurped".[38]

This followed his 1862 book Die Judenspiegel (A Mirror to the Jews) in which he argued that "Judaism must cease to exist if humanity is to commence", demanding both that Judaism be dissolved as a "religious-denominational sect" but also subject to criticism "as a race, a civil and social entity".[39][40] In the introductions to the first through fourth editions of Der Judenspiegel, Marr denied that he intended to preach Jew-hatred, but instead to help "the Jews reach their full human potential" which could happen only "through the downfall of Judaism, a phenomenon that negates everything purely human and noble."[39]

This use of Semitismus was followed by a coining of "Antisemitismus" which was used to indicate opposition to the Jews as a people[41] and opposition to the Jewish spirit, which Marr interpreted as infiltrating German culture.

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year Marr founded the Antisemiten-Liga (League of Antisemites),[42] apparently named to follow the "Anti-Kanzler-Liga" (Anti-Chancellor League).[43] The league was the first German organization committed specifically to combating the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence and advocating their forced removal from the country.[citation needed]

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte, and Wilhelm Scherer used the term Antisemiten in the January issue of Neue Freie Presse.[citation needed]

The Jewish Encyclopedia reports, "In February 1881, a correspondent of the Allgemeine Zeitung des Judentums speaks of 'Anti-Semitism' as a designation which recently came into use ("Allg. Zeit. d. Jud." 1881, p. 138). On 19 July 1882, the editor says, 'This quite recent Anti-Semitism is hardly three years old.'"[44]

The word "antisemitism" was borrowed into English from German in 1881. Oxford English Dictionary editor James Murray wrote that it was not included in the first edition because "Anti-Semite and its family were then probably very new in English use, and not thought likely to be more than passing nonce-words... Would that anti-Semitism had had no more than a fleeting interest!"[45] The related term "philosemitism" was used by 1881.[46]

Usage

From the outset the term "anti-Semitism" bore special racial connotations and meant specifically prejudice against Jews.[4][20][26] The term has been described as confusing, for in modern usage 'Semitic' designates a language group, not a race. In this sense, the term is a misnomer, since there are many speakers of Semitic languages (e.g., Arabs, Ethiopians, and Arameans) who are not the objects of antisemitic prejudices, while there are many Jews who do not speak Hebrew, a Semitic language. Though 'antisemitism' could be construed as prejudice against people who speak other Semitic languages, this is not how the term is commonly used.[47][48][49][50]

The term may be spelled with or without a hyphen (antisemitism or anti-Semitism). Many scholars and institutions favor the unhyphenated form.[1][51][52][53] Shmuel Almog argued, "If you use the hyphenated form, you consider the words 'Semitism', 'Semite', 'Semitic' as meaningful ... [I]n antisemitic parlance, 'Semites' really stands for Jews, just that."[54] Emil Fackenheim supported the unhyphenated spelling, in order to "[dispel] the notion that there is an entity 'Semitism' which 'anti-Semitism' opposes."[55]

Others endorsing an unhyphenated term for the same reason include the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance,[1] historian Deborah Lipstadt,[20] Padraic O'Hare, professor of Religious and Theological Studies and Director of the Center for the Study of Jewish-Christian-Muslim Relations at Merrimack College; and historians Yehuda Bauer and James Carroll. According to Carroll, who first cites O'Hare and Bauer on "the existence of something called 'Semitism'", "the hyphenated word thus reflects the bipolarity that is at the heart of the problem of antisemitism".[56]

The Associated Press and its accompanying AP Stylebook adopted the unhyphenated spelling in 2021.[57] Style guides for other news organizations such as the New York Times and Wall Street Journal later adopted this spelling as well.[58][59] It has also been adopted by many Holocaust museums, such as the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Yad Vashem.[60]

Definition

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice against Jews, and, according to Olaf Blaschke, has become an "umbrella term for negative stereotypes about Jews",[61]: 18 a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions.

Writing in 1987, Holocaust scholar and City University of New York professor Helen Fein defined it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions—social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence—which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."[62]

Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the anti-Semites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."[63]

For Swiss historian Sonja Weinberg, as distinct from economic and religious anti-Judaism, antisemitism in its specifically modern form shows conceptual innovation, a resort to "science" to defend itself, new functional forms, and organisational differences. It was anti-liberal, racialist and nationalist. It promoted the myth that Jews conspired to 'judaise' the world; it served to consolidate social identity; it channeled dissatisfactions among victims of the capitalist system; and it was used as a conservative cultural code to fight emancipation and liberalism.[61]: 18–19

In 2003, Israeli politician Natan Sharansky developed what he called the "three D" test to distinguish antisemitism from criticism of Israel, giving delegitimization, demonization, and double standards as a litmus test for the former.[64][65][66][67]

Bernard Lewis, writing in 2006, defined antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil". Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism.[68]

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. In 2005, the United States Department of State stated that "while there is no universally accepted definition, there is a generally clear understanding of what the term encompasses." For the purposes of its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism, the term was considered to mean "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."[69]

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (EUMC, now the Fundamental Rights Agency), an agency of the European Union, developed a more detailed working definition, which stated: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It also adds that "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity," but that "criticism of Israel similar to that leveled against any other country cannot be regarded as antisemitic."[70] It provided contemporary examples of ways in which antisemitism may manifest itself, including promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, and states that denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, can be a manifestation of antisemitism—as can applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of the State of Israel.[70]

The EUMC working definition was adopted by the European Parliament Working Group on Antisemitism in 2010,[71][non-primary source needed] by the United States Department of State in 2017,[72][non-primary source needed] in the Operational Hate Crime Guidance of the UK College of Policing in 2014[73][non-primary source needed] and by the UK's Campaign Against Antisemitism.[74][non-primary source needed] In 2016, the working definition was adopted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.[75][76] IHRA's Working definition of antisemitism is among the most controversial documents related to opposition to antisemitism, and critics argue that it has been used to censor criticism of Israel.[77] In response to the perceived lack of clarity in the IHRA definition, two new definitions of antisemitism were published in 2021, the Nexus Document in February 2021 and the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism in March 2021.[78][79][80][81][82][83]

Evolution of usage

In 1879, Wilhelm Marr founded the Antisemiten-Liga (Anti-Semitic League).[84] Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe during the late 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger, the popular mayor of fin de siècle Vienna, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage.[85] In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, The New York Times notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria.[86] In 1895, A. C. Cuza organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the period before World War II, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, an organization, or a political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

The early Zionist pioneer Leon Pinsker, a professional physician, preferred the clinical-sounding term Judeophobia to antisemitism, which he regarded as a misnomer. The word Judeophobia first appeared in his pamphlet "Auto-Emancipation", published anonymously in German in September 1882, where it was described as an irrational fear or hatred of Jews. According to Pinsker, this irrational fear was an inherited predisposition.[87]

Judeophobia is a form of demonopathy, with the distinction that the Jewish ghost has become known to the whole race of mankind, not merely to certain races... Judeophobia is a psychic disorder. As a psychic disorder, it is hereditary, and as a disease transmitted for two thousand years it is incurable... Thus have Judaism and Jew-hatred passed through history for centuries as inseparable companions... Having analyzed Judeophobia as a hereditary form of demonopathy, peculiar to the human race, and represented Jew-hatred as based upon an inherited aberration of the human mind, we must draw the important conclusion, that we must give up contending against these hostile impulses, just as we give up contending against every other inherited predisposition.[88]

In the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, German propaganda minister Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."[89]

After 1945 victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany, and particularly after the full extent of the Nazi genocide against the Jews became known, the term antisemitism acquired pejorative connotations. This marked a full circle shift in usage, from an era just decades earlier when "Jew" was used as a pejorative term.[90][91] Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1984: "There are no anti-Semites in the world ... Nobody says, 'I am anti-Semitic.' You cannot, after Hitler. The word has gone out of fashion."[92]

Eternalism–contextualism debate

The study of antisemitism has become politically controversial because of differing interpretations of the Holocaust and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[93] There are two competing views of antisemitism, eternalism, and contextualism.[94] The eternalist view sees antisemitism as separate from other forms of racism and prejudice and an exceptionalist, transhistorical force teleologically culminating in the Holocaust.[94][95] Hannah Arendt criticized this approach, writing that it provoked "the uncomfortable question: 'Why the Jews of all people?' ... with the question begging reply: Eternal hostility."[96] Zionist thinkers and antisemites draw different conclusions from what they perceive as the eternal hatred of Jews; according to antisemites, it proves the inferiority of Jews, while for Zionists it means that Jews need their own state as a refuge.[97][98] Most Zionists do not believe that antisemitism can be combatted with education or other means.[97]

The contextual approach treats antisemitism as a type of racism and focuses on the historical context in which hatred of Jews emerges.[99] Some contextualists restrict the use of "antisemitism" to refer exclusively to the era of modern racism, treating anti-Judaism as a separate phenomenon.[100] Historian David Engel has challenged the project to define antisemitism, arguing that it essentializes Jewish history as one of persecution and discrimination.[101] Engel argues that the term "antisemitism" is not useful in historical analysis because it implies that there are links between anti-Jewish prejudices expressed in different contexts, without evidence of such a connection.[96]

Manifestations

Antisemitism manifests itself in a variety of ways. René König mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of anti-Semitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of anti-Semitism."[102]

These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare, writing in the 1890s, identified three forms of antisemitism: Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.[103] William Brustein names four categories: religious, racial, economic, and political.[104] The Roman Catholic historian Edward Flannery distinguished four varieties of antisemitism:[105]

- Political and economic antisemitism, giving as examples Cicero[106] and Charles Lindbergh;[107]

- Theological or religious antisemitism, also called "traditional antisemitism"[108] and sometimes known as anti-Judaism;[109]

- Nationalistic antisemitism, citing Voltaire and other Enlightenment thinkers, who attacked Jews for supposedly having certain characteristics, such as greed and arrogance, and for observing customs such as kashrut and Shabbat;[110]

- Racial antisemitism, with its extreme form resulting in the Holocaust by the Nazis.[111]

Europe has blamed the Jews for an encyclopedia of sins.

The Church blamed the Jews for killing Jesus; Voltaire blamed the Jews for inventing Christianity. In the febrile minds of anti-Semites, Jews were usurers and well-poisoners and spreaders of disease. Jews were the creators of both communism and capitalism; they were clannish but also cosmopolitan; cowardly and warmongering; self-righteous moralists and defilers of culture.

Ideologues and demagogues of many permutations have understood the Jews to be a singularly malevolent force standing between the world and its perfection.

Jeffrey Goldberg, 2015.[112]

Louis Harap, writing in the 1980s, separated "economic antisemitism" and merges "political" and "nationalistic" antisemitism into "ideological antisemitism". Harap also adds a category of "social antisemitism".[113]

- Religious (Jew as Christ-killer),

- Economic (Jew as banker, usurer, money-obsessed),

- Social (Jew as social inferior, "pushy", vulgar, therefore excluded from personal contact),

- Racist (Jews as an inferior "race"),

- Ideological (Jews regarded as subversive or revolutionary),

- Cultural (Jews regarded as undermining the moral and structural fiber of civilization).

Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism, also known as anti-Judaism, is antipathy towards Jews because of their perceived religious beliefs. In theory, antisemitism and attacks against individual Jews would stop if Jews stopped practicing Judaism or changed their public faith, especially by conversion to the official or right religion. However, in some cases, discrimination continues after conversion, as in the case of Marranos (Christianized Jews in Spain and Portugal) in the late 15th century and 16th century, who were suspected of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs.[105]

Although the origins of antisemitism are rooted in the Judeo-Christian conflict, other forms of antisemitism have developed in modern times. Frederick Schweitzer asserts that "most scholars ignore the Christian foundation on which the modern antisemitic edifice rests and invoke political antisemitism, cultural antisemitism, racism or racial antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and the like."[114] William Nicholls draws a distinction between religious antisemitism and modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds: "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion [...] a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." From the perspective of racial antisemitism, however, "the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism.[...] From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews[...] Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."[115]

Some Christians such as the Catholic priest Ernest Jouin, who published the first French translation of the Protocols, combined religious and racial antisemitism, as in his statement that "From the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality, and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity."[116] The virulent antisemitism of Édouard Drumont, one of the most widely read Catholic writers in France during the Dreyfus Affair, likewise combined religious and racial antisemitism.[117][118][119] Drumont founded the Antisemitic League of France.

Economic antisemitism

The underlying premise of economic antisemitism is that Jews perform harmful economic activities or that economic activities become harmful when they are performed by Jews.[120]

Linking Jews and money underpins the most damaging and lasting antisemitic canards.[121] Antisemites claim that Jews control the world finances, a theory promoted in the fraudulent The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and later repeated by Henry Ford and his The Dearborn Independent. In the modern era, such myths continue to be spread in books such as The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews published by the Nation of Islam and on the internet.

Derek Penslar writes that there are two components to the financial canards:[122]

- a) Jews are savages that "are temperamentally incapable of performing honest labor"

- b) Jews are "leaders of a financial cabal seeking world domination"

Abraham Foxman describes six facets of the financial canards:

- All Jews are wealthy[123]

- Jews are stingy and greedy[124]

- Powerful Jews control the business world[125]

- Jewish religion emphasizes profit and materialism[126]

- It is okay for Jews to cheat non-Jews[127]

- Jews use their power to benefit "their own kind"[128]

Gerald Krefetz summarizes the myth as "[Jews] control the banks, the money supply, the economy, and businesses—of the community, of the country, of the world".[129] Krefetz gives, as illustrations, many slurs and proverbs (in several different languages) which suggest that Jews are stingy, or greedy, or miserly, or aggressive bargainers.[130] During the nineteenth century, Jews were described as "scurrilous, stupid, and tight-fisted", but after the Jewish Emancipation and the rise of Jews to the middle- or upper-class in Europe were portrayed as "clever, devious, and manipulative financiers out to dominate [world finances]".[131]

Léon Poliakov asserts that economic antisemitism is not a distinct form of antisemitism, but merely a manifestation of theologic antisemitism (because, without the theological causes of economic antisemitism, there would be no economic antisemitism). In opposition to this view, Derek Penslar contends that in the modern era, economic antisemitism is "distinct and nearly constant" but theological antisemitism is "often subdued".[132]

An academic study by Francesco D'Acunto, Marcel Prokopczuk, and Michael Weber showed that people who live in areas of Germany that contain the most brutal history of antisemitic persecution are more likely to be distrustful of finance in general. Therefore, they tended to invest less money in the stock market and make poor financial decisions. The study concluded, "that the persecution of minorities reduces not only the long-term wealth of the persecuted but of the persecutors as well."[133]

Racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews as a racial/ethnic group, rather than Judaism as a religion.[135]

Racial antisemitism is the idea that the Jews are a distinct and inferior race compared to their host nations. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, it gained mainstream acceptance as part of the eugenics movement, which categorized non-Europeans as inferior. It more specifically claimed that Northern Europeans, or "Aryans", were superior. Racial antisemites saw the Jews as part of a Semitic race and emphasized their non-European origins and culture. They saw Jews as beyond redemption even if they converted to the majority religion.[136]

Racial antisemitism replaced the hatred of Judaism with the hatred of Jews as a group. In the context of the Industrial Revolution, following the Jewish Emancipation, Jews rapidly urbanized and experienced a period of greater social mobility. With the decreasing role of religion in public life tempering religious antisemitism, a combination of growing nationalism, the rise of eugenics, and resentment at the socio-economic success of the Jews led to the newer, and more virulent, racist antisemitism.[137]

In the early 19th century, a number of laws enabling the emancipation of the Jews were enacted in Western European countries.[138][139] The old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded. Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race of 1853–1855. Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race.[140] Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by northern Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryans to Semitic Jews.[141]

Political antisemitism

The whole problem of the Jews exists only in nation states, for here their energy and higher intelligence, their accumulated capital of spirit and will, gathered from generation to generation through a long schooling in suffering, must become so preponderant as to arouse mass envy and hatred. In almost all contemporary nations, therefore – in direct proportion to the degree to which they act up nationalistically – the literary obscenity of leading the Jews to slaughter as scapegoats of every conceivable public and internal misfortune is spreading.

Friedrich Nietzsche, 1886, [MA 1 475][142]

William Brustein defines political antisemitism as hostility toward Jews based on the belief that Jews seek national or world power. Yisrael Gutman characterizes political antisemitism as tending to "lay responsibility on the Jews for defeats and political economic crises" while seeking to "exploit opposition and resistance to Jewish influence as elements in political party platforms."[143] Derek J. Penslar wrote, "Political antisemitism identified the Jews as responsible for all the anxiety-provoking social forces that characterized modernity."[144]

According to Viktor Karády, political antisemitism became widespread after the legal emancipation of the Jews and sought to reverse some of the consequences of that emancipation.[145]

Cultural antisemitism

Louis Harap defines cultural antisemitism as "that species of anti-Semitism that charges the Jews with corrupting a given culture and attempting to supplant or succeeding in supplanting the preferred culture with a uniform, crude, "Jewish" culture."[146] Similarly, Eric Kandel characterizes cultural antisemitism as being based on the idea of "Jewishness" as a "religious or cultural tradition that is acquired through learning, through distinctive traditions and education." According to Kandel, this form of antisemitism views Jews as possessing "unattractive psychological and social characteristics that are acquired through acculturation."[147] Niewyk and Nicosia characterize cultural antisemitism as focusing on and condemning "the Jews' aloofness from the societies in which they live."[148] An important feature of cultural antisemitism is that it considers the negative attributes of Judaism to be redeemable by education or by religious conversion.[149]

Conspiracy theories

Holocaust denial and Jewish conspiracy theories are also considered forms of antisemitism.[70][150][151][152][153][154][155] Zoological conspiracy theories have been propagated by Arab media and Arabic language websites, alleging a "Zionist plot" behind the use of animals to attack civilians or to conduct espionage.[156]

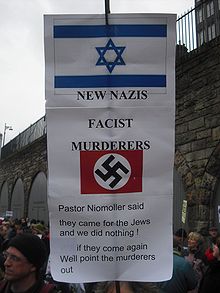

New antisemitism

Starting in the 1990s, some scholars have advanced the concept of new antisemitism, coming simultaneously from the left, the right, and radical Islam, which tends to focus on opposition to the creation of a Jewish homeland in the State of Israel,[157] and they argue that the language of anti-Zionism and criticism of Israel are used to attack Jews more broadly. In this view, the proponents of the new concept believe that criticisms of Israel and Zionism are often disproportionate in degree and unique in kind, and they attribute this to antisemitism.[158]

Jewish scholar Gustavo Perednik posited in 2004 that anti-Zionism in itself represents a form of discrimination against Jews, in that it singles out Jewish national aspirations as an illegitimate and racist endeavor, and "proposes actions that would result in the death of millions of Jews".[158] It is asserted that the new antisemitism deploys traditional antisemitic motifs, including older motifs such as the blood libel.[157]

Critics of the concept view it as trivializing the meaning of antisemitism, and as exploiting antisemitism in order to silence debate and to deflect attention from legitimate criticism of the State of Israel, and, by associating anti-Zionism with antisemitism, misusing it to taint anyone opposed to Israeli actions and policies.[159]

History

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

Many authors see the roots of modern antisemitism in both pagan antiquity and early Christianity. Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:[160]

- Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

- Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

- Traditional Muslim antisemitism which was—at least, in its classical form—nuanced in that Jews were a protected class

- Political, social and economic antisemitism of Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

- Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism in the 20th century

- Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the New Antisemitism

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[161]

Ancient world

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced to the 3rd century BCE to Alexandria,[162] the home to the largest Jewish diaspora community in the world at the time and where the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced. Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian of that era, wrote scathingly of the Jews. His themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus.[163] Agatharchides of Cnidus ridiculed the practices of the Jews and the "absurdity of their Law", making a mocking reference to how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BCE because its inhabitants were observing the Shabbat.[164] One of the earliest anti-Jewish edicts, promulgated by Antiochus IV Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees in Judea.[165]: 238

In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek retelling of Ancient Egyptian prejudices".[166] The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died.[167][168] The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews being portrayed as misanthropes.[169] Tcherikover argues that the reason for hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis.[170] Bohak has argued, however, that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, and that many Greeks showed animosity toward any group they regarded as barbarians.[171]

Statements exhibiting prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek and Roman writers.[172] Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataetus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life." Manetho wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught by Moses "not to adore the gods." Edward Flannery describes antisemitism in ancient times as essentially "cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia played out in political settings."[105]

There are examples of Hellenistic rulers desecrating the Temple and banning Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision, Shabbat observance, the study of Jewish religious books, etc. Examples may also be found in anti-Jewish riots in Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE.

The Jewish diaspora on the Nile island Elephantine, which was founded by mercenaries, experienced the destruction of its temple in 410 BCE.[173]

Relationships between the Jewish people and the occupying Roman Empire were at times antagonistic and resulted in several rebellions. According to Suetonius, the emperor Tiberius expelled from Rome Jews who had gone to live there. The 18th-century English historian Edward Gibbon identified a more tolerant period in Roman–Jewish relations beginning in about 160 CE.[105] However, when Christianity became the state religion of the Roman Empire, the state's attitude towards the Jews gradually worsened.

James Carroll asserted: "Jews accounted for 10% of the total population of the Roman Empire. By that ratio, if other factors such as pogroms and conversions had not intervened, there would be 200 million Jews in the world today, instead of something like 13 million."[174]

Persecutions during the Middle Ages

In the late 6th century CE, the newly Catholicised Visigothic kingdom in Hispania issued a series of anti-Jewish edicts which forbade Jews from marrying Christians, practicing circumcision, and observing Jewish holy days.[175] Continuing throughout the 7th century, both Visigothic kings and the Church were active in creating social aggression and towards Jews with "civic and ecclesiastic punishments",[176] ranging between forced conversion, slavery, exile and death.[177]

From the 9th century, the medieval Islamic world classified Jews and Christians as dhimmis and allowed Jews to practice their religion more freely than they could do in medieval Christian Europe. Under Islamic rule, there was a Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain that lasted until at least the 11th century.[178] It ended when several Muslim pogroms against Jews took place on the Iberian Peninsula, including those that occurred in Córdoba in 1011 and in Granada in 1066.[179][180][181] Several decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues were also enacted in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen from the 11th century. In addition, Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face death in some parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad several times between the 12th and 18th centuries.[182]

The Almohads, who had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and Andalusian territories by 1147,[183] were far more fundamentalist in outlook compared to their predecessors, and they treated the dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians emigrated.[184][185][186] Some, such as the family of Maimonides, fled east to more tolerant Muslim lands,[184] while some others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.[184]

In medieval Europe, Jews were persecuted with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and massacres. These persecutions were often justified on religious grounds and reached a first peak during the Crusades. In 1096, hundreds or thousands of Jews were killed during the First Crusade.[187] This was the first major outbreak of anti-Jewish violence in Christian Europe outside Spain and was cited by Zionists in the 19th century as indicating the need for a state of Israel.[188]

In 1147, there were several massacres of Jews during the Second Crusade. The Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320 both involved attacks, as did the Rintfleisch massacres in 1298. Expulsions followed, such as the 1290 banishment of Jews from England, the expulsion of 100,000 Jews from France in 1394,[189] and the 1421 expulsion of thousands of Jews from Austria. Many of the expelled Jews fled to Poland.[190]

In medieval and Renaissance Europe, a major contributor to the deepening of antisemitic sentiment and legal action among the Christian populations was the popular preaching of the zealous reform religious orders, the Franciscans (especially Bernardino of Feltre) and Dominicans (especially Vincent Ferrer), who combed Europe and promoted antisemitism through their often fiery, emotional appeals.[191]

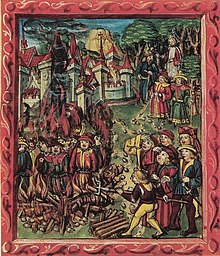

As the Black Death epidemics devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, causing the death of a large part of the population, Jews were used as scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed in numerous persecutions. Although Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by issuing two papal bulls in 1348, the first on 6 July and an additional one several months later, 900 Jews were burned alive in Strasbourg, where the plague had not yet affected the city.[192]

Reformation

Martin Luther, an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his pamphlet On the Jews and their Lies, written in 1543. He portrays the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them, calling for their permanent oppression and expulsion. At one point he writes: "...we are at fault in not slaying them...", a passage that, according to historian Paul Johnson, "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[193]

17th century

During the mid-to-late 17th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was devastated by several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its population (over 3 million people), and Jewish losses were counted in the hundreds of thousands. The first of these conflicts was the Khmelnytsky Uprising, when Bohdan Khmelnytsky's supporters massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the eastern and southern areas he controlled (today's Ukraine). The precise number of dead may never be known, but the decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, which also includes emigration, deaths from diseases, and captivity in the Ottoman Empire, called jasyr.[194][195]

European immigrants to the United States brought antisemitism to the country as early as the 17th century. Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam, implemented plans to prevent Jews from settling in the city. During the Colonial Era, the American government limited the political and economic rights of Jews. It was not until the American Revolutionary War that Jews gained legal rights, including the right to vote. However, even at their peak, the restrictions on Jews in the United States were never as stringent as they had been in Europe.[196]

In the Zaydi imamate of Yemen, Jews were also singled out for discrimination in the 17th century, which culminated in the general expulsion of all Jews from places in Yemen to the arid coastal plain of Tihamah and which became known as the Mawza Exile.[197]

Enlightenment

In 1744, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on the condition that Jews pay for their readmission every ten years. This extortion was known among the Jews as malke-geld ("queen's money" in Yiddish).[198] In 1752, she introduced the law limiting each Jewish family to one son.

In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of these persecution practices in his Toleranzpatent,[199][200] on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew were eliminated from public records and that judicial autonomy was annulled.[201] Moses Mendelssohn wrote that "Such a tolerance... is even more dangerous play in tolerance than open persecution."

Voltaire

According to Arnold Ages, Voltaire's "Lettres philosophiques, Dictionnaire philosophique, and Candide, to name but a few of his better known works, are saturated with comments on Jews and Judaism and the vast majority are negative".[202] Paul H. Meyer adds: "There is no question but that Voltaire, particularly in his latter years, nursed a violent hatred of the Jews and it is equally certain that his animosity...did have a considerable impact on public opinion in France."[203] Thirty of the 118 articles in Voltaire's Dictionnaire Philosophique concerned Jews and described them in consistently negative ways.[204]

Louis de Bonald and the Catholic Counter-Revolution

The counter-revolutionary Catholic royalist Louis de Bonald stands out among the earliest figures to explicitly call for the reversal of Jewish emancipation in the wake of the French Revolution.[205][206] Bonald's attacks on the Jews are likely to have influenced Napoleon's decision to limit the civil rights of Alsatian Jews.[207][208][209][210] Bonald's article Sur les juifs (1806) was one of the most venomous screeds of its era and furnished a paradigm which combined anti-liberalism, a defense of a rural society, traditional Christian antisemitism, and the identification of Jews with bankers and finance capital, which would in turn influence many subsequent right-wing reactionaries such as Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, Charles Maurras, and Édouard Drumont, nationalists such as Maurice Barrès and Paolo Orano, and antisemitic socialists such as Alphonse Toussenel.[205][211][212] Bonald furthermore declared that the Jews were an "alien" people, a "state within a state", and should be forced to wear a distinctive mark to more easily identify and discriminate against them.[205][213]

Under the French Second Empire, the popular counter-revolutionary Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot propagated Bonald's arguments against the Jewish "financial aristocracy" along with vicious attacks against the Talmud and the Jews as a "deicidal people" driven by hatred to "enslave" Christians.[214][213] Between 1882 and 1886 alone, French priests published twenty antisemitic books blaming France's ills on the Jews and urging the government to consign them back to the ghettos, expel them, or hang them from the gallows.[213] Gougenot des Mousseaux's Le Juif, le judaïsme et la judaïsation des peuples chrétiens (1869) has been called a "Bible of modern antisemitism" and was translated into German by Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.[213]

Imperial Russia

Thousands of Jews were slaughtered by Cossack Haidamaks in the 1768 massacre of Uman in the Kingdom of Poland. In 1772, the empress of Russia Catherine II forced the Jews into the Pale of Settlement – which was located primarily in present-day Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus – and to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland. From 1804, Jews were banned from their villages and began to stream into the towns.[215] A decree by emperor Nicholas I of Russia in 1827 conscripted Jews under 18 years of age into the cantonist schools for a 25-year military service in order to promote baptism.[216]

Policy towards Jews was liberalised somewhat under Czar Alexander II (r. 1855–1881).[217] However, his assassination in 1881 served as a pretext for further repression such as the May Laws of 1882. Konstantin Pobedonostsev, nicknamed the "black czar" and tutor to the czarevitch, later crowned Czar Nicholas II, declared that "One-third of the Jews must die, one-third must emigrate, and one third be converted to Christianity".[218]

Islamic antisemitism in the 19th century

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries. Benny Morris writes that one symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. Morris quotes a 19th-century traveler: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."[219]

In the middle of the 19th century, J. J. Benjamin wrote about the life of Persian Jews, describing conditions and beliefs that went back to the 16th century: "…they are obliged to live in a separate part of town… Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt…."[220]

In Jerusalem at least, conditions for some Jews improved. Moses Montefiore, on his seventh visit in 1875, noted that fine new buildings had sprung up and, "surely we're approaching the time to witness God's hallowed promise unto Zion." Muslim and Christian Arabs participated in Purim and Passover; Arabs called the Sephardis 'Jews, sons of Arabs'; the Ulema and the Rabbis offered joint prayers for rain in time of drought.[221]

At the time of the Dreyfus trial in France, "Muslim comments usually favoured the persecuted Jew against his Christian persecutors".[222]

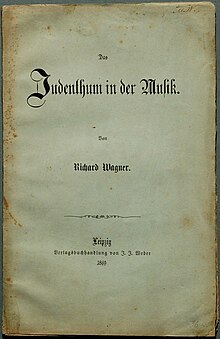

Secular or racial antisemitism

In 1850, the German composer Richard Wagner – who has been called "the inventor of modern antisemitism"[223] – published Das Judenthum in der Musik (roughly "Jewishness in Music"[223]) under a pseudonym in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. The essay began as an attack on Jewish composers, particularly Wagner's contemporaries, and rivals, Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but expanded to accuse Jews of being a harmful and alien element in German culture, who corrupted morals and were, in fact, parasites incapable of creating truly "German" art. The crux was the manipulation and control by the Jews of the money economy:[223]

According to the present constitution of this world, the Jew in truth is already more than emancipated: he rules, and will rule, so long as Money remains the power before which all our doings and our dealings lose their force.[223]

Although originally published anonymously, when the essay was republished 19 years later, in 1869, the concept of the corrupting Jew had become so widely held that Wagner's name was affixed to it.[223]

Antisemitism can also be found in many of the Grimms' Fairy Tales by Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, published from 1812 to 1857. It is mainly characterized by Jews being the villain of a story, such as in "The Good Bargain" ("Der gute Handel") and "The Jew Among Thorns" ("Der Jude im Dorn").

The middle 19th century saw continued official harassment of the Jews, especially in Eastern Europe under Czarist influence. For example, in 1846, 80 Jews approached the governor in Warsaw to retain the right to wear their traditional dress but were immediately rebuffed by having their hair and beards forcefully cut, at their own expense.[224]

Even such influential figures as Walt Whitman tolerated bigotry toward the Jews in America. During his time as editor of the Brooklyn Eagle (1846–1848), the newspaper published historical sketches casting Jews in a bad light.[225]

The Dreyfus Affair was an infamous antisemitic event of the late 19th century and early 20th century. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish artillery captain in the French Army, was accused in 1894 of passing secrets to the Germans. As a result of these charges, Dreyfus was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil's Island. The actual spy, Marie Charles Esterhazy, was acquitted. The event caused great uproar among the French, with the public choosing sides on the issue of whether Dreyfus was actually guilty or not. Émile Zola accused the army of corrupting the French justice system. However, general consensus held that Dreyfus was guilty: 80% of the press in France condemned him. This attitude among the majority of the French population reveals the underlying antisemitism of the time period.[226]

Adolf Stoecker (1835–1909), the Lutheran court chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, founded in 1878 an antisemitic, anti-liberal political party called the Christian Social Party.[227][228] This party always remained small, and its support dwindled after Stoecker's death, with most of its members eventually joining larger conservative groups such as the German National People's Party.

Some scholars view Karl Marx's essay "On The Jewish Question" as antisemitic, and argue that he often used antisemitic epithets in his published and private writings.[229][230][231] These scholars argue that Marx equated Judaism with capitalism in his essay, helping to spread that idea. Some further argue that the essay influenced National Socialist, as well as Soviet and Arab antisemites.[232][233][234] Marx himself had Jewish ancestry, and Albert Lindemann and Hyam Maccoby have suggested that he was embarrassed by it.[235][236]

Others argue that Marx consistently supported Prussian Jewish communities' struggles to achieve equal political rights. These scholars argue that "On the Jewish Question" is a critique of Bruno Bauer's arguments that Jews must convert to Christianity before being emancipated, and is more generally a critique of liberal rights discourses and capitalism.[237][238][239][240] Iain Hamphsher-Monk wrote that "This work [On The Jewish Question] has been cited as evidence for Marx's supposed anti-semitism, but only the most superficial reading of it could sustain such an interpretation."[241]

David McLellan and Francis Wheen argue that readers should interpret On the Jewish Question in the deeper context of Marx's debates with Bruno Bauer, author of The Jewish Question, about Jewish emancipation in Germany. Wheen says that "Those critics, who see this as a foretaste of 'Mein Kampf', overlook one, essential point: in spite of the clumsy phraseology and crude stereotyping, the essay was actually written as a defense of the Jews. It was a retort to Bruno Bauer, who had argued that Jews should not be granted full civic rights and freedoms unless they were baptised as Christians".[242] According to McLellan, Marx used the word Judentum colloquially, as meaning commerce, arguing that Germans must be emancipated from the capitalist mode of production not Judaism or Jews in particular. McLellan concludes that readers should interpret the essay's second half as "an extended pun at Bauer's expense".[243]

20th century

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews migrated to America, the bulk from Eastern Europe escaping the pogroms. This increase, combined with the upward social mobility of some Jews, contributed to a resurgence of antisemitism. In the first half of the 20th century, in the US, Jews were discriminated against in employment, access to residential and resort areas, membership in clubs and organizations, and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrolment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. The lynching of Leo Frank by a mob of prominent citizens in Marietta, Georgia, in 1915 turned the spotlight on antisemitism in the United States.[244] The case was also used to build support for the renewal of the Ku Klux Klan which had been inactive since 1870.[245]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Beilis Trial in Russia represented modern incidents of blood-libels in Europe. During the Russian Civil War, close to 50,000 Jews were killed in pogroms.[246]

Antisemitism in America reached its peak during the interwar period. The pioneer automobile manufacturer Henry Ford propagated antisemitic ideas in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent (published by Ford from 1919 to 1927). The radio speeches of Father Coughlin in the late 1930s attacked Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal and promoted the notion of a Jewish financial conspiracy. Some prominent politicians shared such views: Louis T. McFadden, Chairman of the United States House Committee on Banking and Currency, blamed Jews for Roosevelt's decision to abandon the gold standard, and claimed that "in the United States today, the Gentiles have the slips of paper while the Jews have the lawful money".[247]

In Germany, shortly after Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, the government instituted repressive legislation which denied Jews basic civil rights.[248][249]

In September 1935, the Nuremberg Laws prohibited sexual relations and marriages between "Aryans" and Jews as Rassenschande ("race disgrace") and stripped all German Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, of their citizenship (their official title became "subjects of the state").[250] It instituted a pogrom on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed Kristallnacht, in which Jews were killed, their property destroyed and their synagogues torched.[251] Antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were extended to German-occupied Europe in the wake of conquest, often building on local antisemitic traditions.

In 1940, the famous aviator Charles Lindbergh and many prominent Americans led the America First Committee in opposing any involvement in a European war. Lindbergh alleged that Jews were pushing America to go to war against Germany.[252][253][254] Lindbergh adamantly denied being antisemitic, and yet he refers numerous times in his private writings – his letters and diary – to Jewish control of the media being used to pressure the U.S. to get involved in the European war. In one diary entry in November 1938, he responded to Kristallnacht by writing "I do not understand these riots on the part of the Germans. ... They have undoubtedly had a difficult Jewish problem, but why is it necessary to handle it so unreasonably?", acknowledgement on Lindbergh's part that he agreed with the Nazis that Germany had a "Jewish problem".[255] An article by Jonathan Marwil in Antisemitism, A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution claims that "no one who ever knew Lindbergh thought him antisemitic" and that claims of his antisemitism were solely tied to the remarks he made in that one speech.[256]

In the east the Third Reich forced Jews into ghettos in Warsaw, in Kraków, in Lvov, in Lublin and in Radom.[257] After the beginning of the war between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in 1941, a campaign of mass murder, conducted by the Einsatzgruppen, culminated from 1942 to 1945 in systematic genocide: the Holocaust.[258] Eleven million Jews were targeted for extermination by the Nazis, and some six million were eventually killed.[258][259][260]

Contemporary antisemitism

Post-WWII antisemitism

There have continued to be antisemitic incidents since WWII, some of which had been state-sponsored. In the Soviet Union, antisemitism was even used as an instrument for settling personal conflicts, starting with the conflict between Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky and continuing through numerous conspiracy theories spread by official propaganda. Antisemitism in the USSR reached new heights after 1948 during the campaign against the "rootless cosmopolitan" (euphemism for "Jew") in which numerous Yiddish-language poets, writers, painters, and sculptors were killed or arrested.[261][262] This culminated in the antisemitic conspiracy theory of the 'Doctors' Plot' in 1952.

In the 20th century, Soviet and Russian antisemitism underwent significant transformations, shaped by political, social, and ideological shifts. During the early Soviet period, the Bolsheviks initially condemned antisemitism, seeing it as incompatible with Marxist ideology. However, under Joseph Stalin's regime, antisemitism reemerged, often cloaked in 'anti-Zionist' rhetoric. As early as 1943, Stalin and his propagandists intensified attacks against Jews as "rootless cosmopolitans".[263] The Party issued confidential directives to fire Jews from positions of power, but state-controlled media did not openly attack Jews until the late 1940s.[263] The Doctors' plot of 1952, a fabricated conspiracy accusing predominantly Jewish doctors of attempting to assassinate Soviet leaders, exemplified this resurgence. This campaign fostered widespread antisemitic sentiments and resulted in the arrest and execution of numerous Jewish professionals.

In that same year, the antisemitic Slánský show trial alleged the existence of an 'international Zionist conspiracy' to destroy Socialism. Izabella Tabarovsky, a scholar of the history of antisemitism, argues that, "Manufactured by the Soviet secret services, the trial tied together Zionism, Israel, Jewish leaders, and American imperialism, turning 'Zionism' and 'Zionist' into dangerous labels that could be used against one's political enemies."[264] In the post-Stalin era, state-sanctioned antisemitism persisted and intensified.In February 1953, the Soviet Union severed diplomatic relations with the State of Israel and "soon the state media was saturated with anti-Zionist propaganda, depicting bloated, hook-nosed Jewish bankers and all-consuming serpents embossed with the Star of David."[265] The 1963 publication of the antisemitic book Judaism Without Embellishment, written under orders from the central Soviet government, echoed Nazi propaganda, alleging a global Jewish conspiracy to subvert the Soviet Union.[264] It was the beginning of a new wave of government-sponsored anti-Semitism.

The Six-Day War in 1967 led to an intensification in Soviet anti-Zionist propaganda as the Soviets had backed the defeated Arab states.[264] This propaganda often blurred the lines with antisemitism, leading to discriminatory policies against Jews and restricting their emigration. By the end of the war, "the "corporate Jew", whether "cosmopolitan" or "Zionist", became identified as the enemy. Popular anti-Semitic stereotyping had been absorbed into official channels, generated by chauvinist needs and totalitarian requirements."[266] The Anti-Zionist Committee of the Soviet Public shut down and expropriated synagogues, yeshivas, and Jewish civil organisations and prohibited the learning of Hebrew. It also engaged in a wide-scale propaganda campaign between 1967 and 1988 overseen by the KGB and published pamphlets featuring antisemitic conspiracy theories, for example falsely claiming that Zionist Jews collaborated with the Nazi regime in the Holocaust and of inflating the significance and scale of anti-Jewish persecution.[264]

Their propaganda frequently borrowed directly from the forged Protocols of the Elders of Zion and sometimes relied upon Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf as a source of information about Zionism.[264] Antizionism helped Moscow "bond both with its Arab allies and the Western hard left of all shades. Having appointed Zionism as a scapegoat for humanity's greatest evils, Soviet propaganda could score points by equating it with racism in African radio broadcasts and with Ukrainian nationalism on Kyiv TV."[267] The still-extant Novosti Press Agency, a key element in the Soviet propaganda machine, also participated in the spreading of antisemitic anti-Zionism. Its chairman, Ivan Udaltsov, published a memorandum on 27 January 1971, to the CPSU in which he claimed that "Zionists, by provoking antisemitism, recruit volunteers for the Israeli army", blaming Jews for antisemitism, and falsely alleged that Zionists were responsible for "subversive activities" during the 1968 Prague Spring.[267] According to historian William Korey, "Judaism was singled out for condemnation as prescribing 'racial exclusivism' and as justifying 'crimes against 'Gentiles.'"[266]

Similar antisemitic propaganda in Poland resulted in the flight of Polish Jewish survivors from the country.[262] After the war, the Kielce pogrom and the "March 1968 events" in communist Poland represented further incidents of antisemitism in Europe. The anti-Jewish violence in postwar Poland had a common theme of blood libel rumours.[268][269]

21st-century European antisemitism

Physical assaults against Jews in Europe have included beatings, stabbings, and other violence, which increased markedly, sometimes resulting in serious injury and death.[270][271] A 2015 report by the US State Department on religious freedom declared that "European anti-Israel sentiment crossed the line into anti-Semitism."[272]

This rise in antisemitic attacks is associated with both Muslim antisemitism and the rise of far-right political parties as a result of the economic crisis of 2008.[273] This rise in the support for far-right ideas in western and eastern Europe has resulted in the increase of antisemitic acts, mostly attacks on Jewish memorials, synagogues and cemeteries but also a number of physical attacks against Jews.[274]

In Eastern Europe the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the instability of the new states brought the rise of nationalist movements and the accusation against Jews for the economic crisis, taking over the local economy and bribing the government, along with traditional and religious motives for antisemitism such as blood libels. Writing on the rhetoric surrounding the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Jason Stanley relates these perceptions to broader historical narratives: "the dominant version of antisemitism alive in parts of eastern Europe today is that Jews employ the Holocaust to seize the victimhood narrative from the 'real' victims of the Nazis, who are Russian Christians (or other non-Jewish eastern Europeans)".[275] He calls out the "myths of contemporary eastern European antisemitism – that a global cabal of Jews were (and are) the real agents of violence against Russian Christians and the real victims of the Nazis were not the Jews, but rather this group."[275]

Most of the antisemitic incidents in Eastern Europe are against Jewish cemeteries and buildings (community centers and synagogues). Nevertheless, there were several violent attacks against Jews in Moscow in 2006 when a neo-Nazi stabbed 9 people at the Bolshaya Bronnaya Synagogue,[276] the failed bomb attack on the same synagogue in 1999,[277] the threats against Jewish pilgrims in Uman, Ukraine[278] and the attack against a menorah by extremist Christian organization in Moldova in 2009.[279]

According to Paul Johnson, antisemitic policies are a sign of a state which is poorly governed.[280] While no European state currently has such policies, the Economist Intelligence Unit notes the rise in political uncertainty, notably populism and nationalism, as something that is particularly alarming for Jews.[281]

21st-century Arab antisemitism

Robert Bernstein, founder of Human Rights Watch, says that antisemitism is "deeply ingrained and institutionalized" in "Arab nations in modern times".[282]

In a 2011 survey by the Pew Research Center, all of the Muslim-majority Middle Eastern countries polled held significantly negative opinions of Jews. In the questionnaire, only 2% of Egyptians, 3% of Lebanese Muslims, and 2% of Jordanians reported having a positive view of Jews. Muslim-majority countries outside the Middle East similarly held markedly negative views of Jews, with 4% of Turks and 9% of Indonesians viewing Jews favorably.[283]

According to a 2011 exhibition at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, United States, some of the dialogue from Middle East media and commentators about Jews bear a striking resemblance to Nazi propaganda.[284] According to Josef Joffe of Newsweek, "anti-Semitism—the real stuff, not just bad-mouthing particular Israeli policies—is as much part of Arab life today as the hijab or the hookah. Whereas this darkest of creeds is no longer tolerated in polite society in the West, in the Arab world, Jew hatred remains culturally endemic."[285]

Muslim clerics in the Middle East have frequently referred to Jews as descendants of apes and pigs, which are conventional epithets for Jews and Christians.[286][287][288]

According to professor Robert Wistrich, director of the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism (SICSA), the calls for the destruction of Israel by Iran or by Hamas, Hezbollah, Islamic Jihad, or the Muslim Brotherhood, represent a contemporary mode of genocidal antisemitism.[289]

21st-century antisemitism at universities

After the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel on 7 October, antisemitism and anti-Jewish hate crimes around the world increased significantly.[290][291][292] Multiple universities and university officials have been accused of systemic antisemitism.[293][294][295] On 1 May 2024, the United States House of Representatives voted 320–91 in favour of adopting a bill enshrining the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism into law.[296] The bill was opposed by some who claimed it conflated criticism of Israel with antisemitism, while Jewish advocacy groups like the American Jewish Committee and World Jewish Congress generally supported it in response to the increase in antisemitic incidents on university campuses.[297][298] An open letter by 1,200 Jewish professors opposed the proposal.[299]

Black Hebrew Israelite antisemitism

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (July 2024) |

In 2022, the American Jewish Committee stated that the Black Hebrew Israelite claim that "we are the real Jews" is a "troubling anti-Semitic trope with dangerous potential".[302] Black Hebrew Israelite followers have sought out and attacked Jewish people in the United States on more than one occasion.[303][304] Between 2019 and 2022, individuals motivated by Black Hebrew Israelitism committed five religiously motivated murders.[301]

Black Hebrew Israelites believe that Jewish people are "imposters", who have "stolen" Black Americans' true racial and religious identity.[301] Black Hebrew Israelites promote the Khazar theory about Ashkenazi Jewish origins.[301] In 2019, 4% of African-Americans self-identified as being Black Hebrew Israelites.[300]

Antisemitism on the internet

Antisemitism on the internet involves a complex interplay between social media dynamics, conspiracy theories, and the broader socio-political context. Social media platforms have proved fertile for breeding antisemitic rhetoric, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, during which a notable rise in antisemitic conspiracy theories emerged.[305][306][307] The role of social media in amplifying these sentiments is underscored by analyses of comment sections on major media outlets, which reveal a significant presence of antisemitic discourse, often framed within the context of political events and international relations.[308][309] Furthermore, the emergence of TikTok as a new platform has raised concerns about the proliferation of antisemitic content, with studies highlighting the challenges of moderating such material effectively.[310][311] The intersection of antisemitism with broader themes of populism and right-wing extremism is also evident, as these ideologies often utilize antisemitic narratives to galvanize support and create a sense of otherness.[309][312] Additionally, the phenomenon of subtle hate speech has been identified, where antisemitic sentiments are recontextualized in ways that may evade direct detection yet still perpetuate harmful stereotypes.[313] Antisemitic bias appears even in ostensibly neutral sources such as on the Wikipedia platform.[314] Overall, the digital landscape presents both challenges and opportunities for combating antisemitism, necessitating a multifaceted approach that includes community engagement and technological solutions to monitor and counteract hate speech effectively.[315][316]

Causes

Antisemitism has been explained in terms of racism, xenophobia, projected guilt, displaced aggression, conspiracy theory, and the search for a scapegoat.[317]

Antisemitism scholar Lars Fischer writes that "scholars distinguish between theories that assume an actual causal (rather than merely coincidental) correlation between what (some) Jews do and antisemitic perceptions (correspondence theories), on the one hand, and those predicated on the notion that no such causal correlation exists and that 'the Jews' serve as a foil for the projection of antisemitic assumptions, on the other."[318] The latter position is exemplified by Theodor W. Adorno, who wrote that "Anti-Semitism is the rumour about the Jews"; in other words, "a conspiratorial mentality that sees Jewish people as invisible and yet ubiquitous, as capable of pulling the strings of power from behind the scenes."[319][320]

As an example of the correspondence theory, an 1894 book by Bernard Lazare questions whether Jews themselves were to blame for some antisemitic stereotypes, for instance arguing that Jews traditionally keeping strictly to their own communities, with their own practices and laws, led to a perception of Jews as anti-social; he later abandoned this belief and the book is considered antisemitic today.[321][322][323] As another example, Walter Laqueur suggested that the antisemitic perception of Jewish people as greedy (as often used in stereotypes of Jews) probably evolved in Europe during medieval times where a large portion of money lending was operated by Jews.[324] Among factors thought to contribute to this situation include that Jews were restricted from other professions,[324] while the Christian Church declared for their followers that money lending constituted immoral "usury",[325] although recent scholarship, such as that of historian Julie Mell shows that Jews were not overrepresented in the sector and that the stereotype was founded in Christian projection of taboo behaviour on to the minority.[318][326][327]

In Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition (2013), historian David Nirenberg traces the history of antisemitism, arguing that antisemitism should be understood not as a product of isolated historical events or cultural biases but is instead embedded within the very fabric of Western thought and society.[328] Its foundation lies in the early claim of Jewish deicide and depictions of Jews as 'Christ-killers'. Throughout Western history, Jews have since been used as a symbolic 'other' to define and articulate the values and boundaries of various cultures and intellectual traditions. In philosophy, literature, and politics, Jewishness has often been constructed as a counterpoint to what is considered normative or ideal. One of the key insights from Nirenberg's work is that antisemitism has proven to be remarkably adaptable. It changes form and adapts to different contexts and times, whether in medieval religious disputes, Enlightenment critiques, or modern racial theories. Philosophers and intellectuals have often used 'Jewishness' as a foil to explore and define their ideas. For instance, in the Enlightenment, figures like Voltaire critiqued Judaism as backward and superstitious to promote their visions of reason and progress. Similarly, the Soviet Union frequently portrayed Judaism as linked with capitalism and mercantilism, standing in opposition to the ideals of proletarian solidarity and communism. In each case, Judaism or the Jews are portrayed as standing in tension with prevailing moral norms.[328]

British quantum physicist David Deutsch has argued that antisemites have historically always attempted to provide some sort of justification for their persecution of Jews. He uses the term 'The Pattern' to describe what he argues underlies historical antisemitism: "the maintenance of the idea that it is legitimate to hurt Jews."[329] He provides the following examples:

- The idea that Jews have collectively failed some crucial test (e.g. they rejected Jesus, or Mohammed, or do not have the Aryans' capacity for 'culture', or do not satisfy Stalin's criteria for being a 'nation', or lack a mystical 'connection to the land', etc.);