Anti-Serb sentiment

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Anti-Serb sentiment or Serbophobia (Serbian: србофобија / srbofobija) is a generally negative view of Serbs as an ethnic group. Historically it has been a basis for the persecution of ethnic Serbs.

A distinctive form of anti-Serb sentiment is anti-Serbian sentiment, which can be defined as a generally negative view of Serbia as a nation-state for Serbs. Another form of anti-Serb sentiment is a generally negative view of Republika Srpska, the Serb-majority entity in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The best known historical proponent of anti-Serb sentiment was the 19th- and 20th-century Croatian Party of Rights. The most extreme elements of this party became the Ustaše in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, a Croatian fascist organization that came to power during World War II and instituted racial laws that specifically targeted Serbs, Jews, Roma and dissidents. This culminated in the genocide of Serbs and members of other minority groups that lived in the Independent State of Croatia.

History

Before World War I

Turks and Albanians in Ottoman Kosovo Vilayet

Anti-Serb sentiment in the Kosovo Vilayet grew as a result of the Ottoman-Serb and Ottoman-Greek conflicts during the period of 1877–1897. With the Battle of Vranje in 1878, thousands of Ottoman-Albanian troops and Albanian civilians were expelled into the Eastern part of Ottoman-held Kosovo Vilayet.[1] These displaced persons known as (Alb. muhaxhirë, Turk. muhacir, Serb. muhadžir) were highly hostile towards the Serbs in the areas they retreated to, given the fact that they were expelled from the Vranje area due to the Ottoman-Serb conflict.[2] This animosity fuelled anti-Serb sentiment which resulted in Albanians committing widespread atrocities including killings against Serb civilians across the entire territory, including parts of Pristina and Bujanovac.[3]

Atrocities against Serbs in the region also peaked in 1901 after the region was flooded with weapons not handed back to the Ottomans after the Greco-Turkish War of 1897.[4] In May 1901, Albanians pillaged and partially burned the cities of Novi Pazar, Sjenica and Pristina, and massacred Serbs in the area of Kolašin.[5][6] David Little suggests that the actions of Albanians at the time constituted ethnic cleansing as they attempted to create a homogeneous area free of Christian Serbs.[7]

Bulgarians in Ottoman Macedonia

The Society Against Serbs was a Bulgarian nationalist organization, established in 1897 in Thessaloniki, Ottoman Empire. The organization's activists were both "Centralists" and "Vrhovnists" of the Bulgarian revolutionary committees (the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and the Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee), and had by 1902 murdered at least 43 and wounded 52, owners of Serbian schools, teachers, Serbian Orthodox clergy, and other notable Serbs in the Ottoman Empire.[8] Bulgarians also used the term "Serbomans" for people of non-Serbian origin, but with Serbian self-determination in Macedonia.

19th and early 20th century in the Habsburg monarchy

Anti-Serbian sentiment coalesced in 19th-century Croatia when some of the Croatian intelligentsia planned the creation of a Croatian nation-state.[9] Croatia was at the time a part of the Habsburg monarchy while since 1804 the Austrian Empire, although remained in personal union with the Kingdom of Hungary. After the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, it was part of Tranleithania, while Dalmatia and Istria remained separate Austrian crown lands. Ante Starčević, the leader of the Party of Rights between 1851 and 1896, believed Croats should confront their neighbors, including Serbs.[10] He wrote, for example, that Serbs were an "unclean race" and with the co-founder of his party, Eugen Kvaternik, denied the existence of Serbs or Slovenes in Croatia, seeing their political consciousness as a threat.[11][12] During the 1850s Starčević forged the term Slavoserb (Latin: sclavus, servus) to describe people supposedly ready to serve foreign rulers, initially used to refer to some Serbs and his Croat opponent and later applied to all Serbs by his followers.[13] The Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878 probably contributed to the development of Starčević's anti-Serb sentiment: He believed that it increased the chances for the creation of Greater Croatia.[14] David Bruce MacDonald, has put forward a thesis that Starčević's theories could only justify ethnocide but not genocide because Starčević intended to assimilate Serbs as "Orthodox Croats", and not to exterminate them.[15]

Starčević's ideas formed a basis for the destructive politics of his successor, Josip Frank, a Croatian Jewish lawyer and politician converted to Catholicism[16][17] who led numerous anti-Serbian incidents.[10] Josip Frank carried on Starčević's ideology, and defined Croat identity 'strictly in terms of Serbophobia'.[18] He opposed any cooperation between Croats and Serbs, and Djilas described him as "a leading anti-Serbian demagogue and the instigator of the persecution of Serbs in Croatia".[18] His followers, called Frankovci, would go on to become the most ardent Ustashe members.[18] Under Frank's leadership the Party of Rights became obsessively anti-Serb,[19][20] and such sentiments dominated Croatian political life in the 1880s.[21] British historian C. A. Macartney stated that because of the "gross intolerance" toward Serbs who lived in Slavonia, they had to seek protection from Count Károly Khuen-Héderváry, the Ban of Croatia-Slavonia, in 1883.[22] During his reign in 1883–1903, Hungary stimulated division and hatred between Serbs and Croats to further its Magyarization policy.[22] Carmichael writes that ethnic division between the Croats and the Serbs at the turn of the 20th century was stoked by a nationalist press and was "incubated entirely in the minds of extremists and fanatics, with little evidence that the areas in which Serbs and Croats had lived for many centuries in close proximity, such as Krajina, were more prone to ethnically inspired violence."[14] In 1902 major anti-Serb riots in Croatia were caused by an article written by Serbian nationalist writer Nikola Stojanović (1880–1964) titled Do istrage vaše ili naše (Till the destruction of you or us) which forecasted the result of an "inevitable" Serbian-Croatian conflict, that was reprinted in the Serb Independent Party's Srbobran magazine.[23]

Between the mid-19th and early 20th century there were two factions in the Catholic Church in Croatia: the progressive faction which preferred uniting Croatia with Serbia in a progressive Slavic country, and the conservative faction that opposed this.[24] The conservative faction became dominant by the end of the 19th century: The First Croatian Catholic Congress held in Zagreb in 1900 was unreservedly Serbophobic and anti-Orthodox.[24]

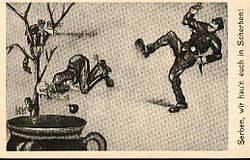

World War I

After the Balkan Wars in 1912–1913, anti-Serb sentiment increased in the Austro-Hungarian administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[25] Oskar Potiorek, governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, closed many Serb societies and significantly contributed to the anti-Serb mood before the outbreak of World War I.[25] [26]

The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg in 1914 led to the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo. Ivo Andrić refers to this event as the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate."[27] The crowds directed their anger principally at Serb shops, residences of prominent Serbs, the Serbian Orthodox Church, schools, banks, the Serb cultural society Prosvjeta, and the Srpska riječ newspaper offices. Two Serbs were killed that day.[28] That night there were anti-Serb riots in other parts of the Austro-Hungarian Empire[29] including Zagreb and Dubrovnik. [30] In the aftermath of the Sarajevo assassination anti-Serb sentiment ran high throughout the Habsburg Empire.[31] Austria-Hungary imprisoned and extradited around 5,500 prominent Serbs, sentenced 460 to death, and established the predominantly Muslim[32] special militia Schutzkorps which carried on the persecution of Serbs.[33]

The Sarajevo assassination became the casus belli for World War I.[34] Taking advantage of an international wave of revulsion against this act of "Serbian nationalist terrorism," Austria-Hungary gave Serbia an ultimatum which led to World War I. Although the Serbs of Austria-Hungary were loyal citizens whose majority participated in its forces during the war, anti-Serb sentiment systematically spread and members of the ethnic group were persecuted all over the country.[35] Austria-Hungary soon occupied the territory of the Kingdom of Serbia, including Kosovo, boosting already intense anti-Serbian sentiment among Albanians whose volunteer units were established to reduce the number of Serbs in Kosovo.[36] A cultural example is the jingle "Alle Serben müssen sterben" ("All Serbs Must Die"), which was popular in Vienna in 1914. (It was also known as "Serbien muß sterbien").[37]

Orders issued on 3 and 13 October 1914 banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia, limiting it to use in religious instruction. A decree was passed on 3 January 1915, that banned Serbian Cyrillic completely from public use. An imperial order on 25 October 1915, banned the use of Serbian Cyrillic in the Condominium of Bosnia and Herzegovina, except "within the scope of Serb Orthodox Church authorities".[38][39]

Interwar period

Fascist Italy

In the 1920s, Italian fascists accused Serbs of having "atavistic impulses" and they claimed that the Yugoslavs were conspiring together on behalf of "Grand Orient masonry and its funds". One antisemitic claim was that Serbs were part of a "social-democratic, masonic Jewish internationalist plot".[40] Benito Mussolini viewed not just the Serbs but the whole "Slavic race" as inferior and barbaric.[41] He identified the Yugoslavs as a threat to Italy and he claimed that the threat rallied Italians together at the end of World War I: "The danger of seeing the Jugo-Slavians settle along the whole Adriatic shore had caused a bringing together in Rome of the cream of our unhappy regions. Students, professors, workmen, citizens—representative men—were entreating the ministers and the professional politicians".[42]

Croats in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The relations between Croats and Serbs were stressed at the very beginning of the Yugoslav state.[43] Opponents to the Yugoslav unification in the Croatian elite portrayed Serbs negatively, as hegemonists and exploiters, introducing Serbophobia into Croatian society.[43] It was reported that in Lika, there was serious tension between Croats and Serbs.[44] In post-war Osijek, the Šajkača hat was banned by the police but the Austro-Hungarian cap was freely worn, and in the school and judicial system the Orthodox Serbs were termed "Greek-Eastern".[45] There was voluntary segregation in Knin.[46]

A 1993 report of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe stated that Belgrade's centralist policies for the Kingdom of Yugoslavia led to increased anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia.[47]

World War II

Nazi Germany

Serbs as well as other Slavs (mainly Poles and Russians) as well as non-Slavic peoples (such as Jews and Roma) were not considered Aryans by Nazi Germany. Instead, they were considered subhuman, inferior races (Untermenschen) and foreign races and as a result, they were not considered part of the Aryan master race.[48][49] Serbs, along with the Poles, were at the bottom of the Slavic "racial hierarchy" established by the Nazis.[50] Anti-Serb sentiment increasingly infiltrated German Nazism after Adolf Hitler's appointment as chancellor in 1933. The roots of this sentiment can be found in his early life in Vienna,[51] and when he was informed about the Yugoslav coup d'état that was conducted by a group of pro-Western Serb officers in March 1941, he decided to punish all Serbs as the main enemies of his new Nazi order.[52] The propaganda ministry of Joseph Goebbels, with the support of the Bulgarian, Italian, and Hungarian press, was given the task of stimulating anti-Serb sentiment among the Croats, Slovenians and Hungarians.[53] The propaganda of the Axis powers accused the group of persecuting minorities and establishing concentration camps for ethnic Germans in order to justify an attack on Yugoslavia and Nazi Germany portrayed itself as a force which would save the Yugoslav people from the threat of Serb nationalism.[53] In 1941 Yugoslavia was invaded and occupied by the Axis powers.

Independent State of Croatia and Ustashe

The Axis occupation of Serbia enabled the Ustashe, a Croatian fascist[54] and terrorist organization, to implement its extreme anti-Serbian ideology in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH).[55] Its anti-Serb sentiment was racist and genocidal.[56][57] The new government adopted racial laws, similar to those which existed in Nazi Germany, and it aimed them at Jews, Roma people and Serbs, who were all defined as being "aliens outside the national community"[58] and persecuted throughout the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) during World War II.[59] Between 200,000 and 500,000 Serbs were killed in the NDH by the Ustaše and their Axis allies.[60][61] Overall, the number of Serbs who were killed in Yugoslavia during World War II was about 700,000, the majority of whom were massacred by various fascist forces.[62][63] Many historians and authors describe the Ustaše regime's mass killings of Serbs as meeting the definition of genocide, including Raphael Lemkin who is known for coining the word genocide and initiating the Genocide Convention.[64][65][66][67][68][69] Sisak concentration camp was set up on 3 August 1942 by the Ustaše government following the Kozara Offensive and it was specially formed for children.[70][71][72]

Some priests in the Croatian Catholic Church participated in these Ustaša massacres and the mass conversion of Serbs to Catholicism.[73] During the war, about 250,000 people of the Orthodox faith who were living within the territory of the NDH were either forced or coerced into converting to Catholicism by the Ustaša authorities.[74] One of the reasons for the close cooperation of a part of the Catholic clergy was its anti-Serb position.[75]

Albania

When Kosovo became part of Serbia after WWI, the Yugoslav authorities expelled 400,000 Albanians from Kosovo in the interwar period and promoted the settlement of mostly Serb colonists in the region.[76] In WWII, western and central Kosovo became part of Albania and Kosovo Albanians enacted brutal reprisals against the colonists.[77] During the Italian occupation of Albania in WWII, between 70,000 and 100,000 Serbs were expelled and thousands massacred in annexed Kosovo by Albanian paramilitaries, mainly by the Vulnetari and Balli Kombëtar.[76][78]

Xhafer Deva recruited Kosovo Albanians to join the Waffen-SS.[79] The 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian) was formed on 1 May 1944,[80] composed of ethnic Albanians, named after Albanian national hero Skanderbeg who fought the Ottomans in the 15th century.[81] The division was better known for murdering, raping, and looting in predominantly Serbian areas than for participating in combat operations on behalf of the German war effort.[82] Deva and his collaborators were anti-Slavic and advocated for an ethnically pure "Greater Albania".[83] By September 1944, with the Allied victory in the Balkans imminent, Deva and his men attempted to purchase weapons from withdrawing German soldiers in order to organize a "final solution" of the Slavic population of Kosovo. Nothing came of this as the powerful Yugoslav Partisans prevented any large-scale ethnic cleansing of Slavs from occurring.[78]

These conflicts were relatively low-level compared with other areas of Yugoslavia during the war years.[84] Approximately 10,000 Serbs and Montenegrins died in Kosovo during the war, the majority of whom were killed by Albanian collaborationist forces.[77] Two Serb historians also estimate that 12,000 Albanians lost their lives.[84] An official investigation conducted by the Yugoslav government in 1964 recorded nearly 8,000 war-related fatalities in Kosovo between 1941 and 1945, 5,489 of whom were Serb and Montenegrin and 2,177 of whom were Albanian.[85]

After World War II

Nearly four decades later, in the 1986 draft of the Memorandum of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, concern was expressed that Serbophobia, together with other things, could provoke the restoration of Serbian nationalism with dangerous consequences.[86] The 1987 Yugoslav economic crisis, and different opinions within Serbia and other republics about what were the best ways to resolve it, exacerbated growing anti-Serbian sentiment among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Serbian nationalism.[87]

Breakup of Yugoslavia

During the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, anti-Serb sentiment flooded Croatia, Bosnia and Kosovo,[88] and because of its independence and its historical association with Serbophobia, the Independent State of Croatia would sometimes serve as a rallying symbol for people who intended to proclaim aversion towards Serbia.[89] It also worked vice versa. And while the Serbian nationalism of the time is well-known, anti-Serb sentiment was present in all non-Serb republics of Yugoslavia during its breakup.[90] Bookocide of works written in Serbian took place in Croatia, with as many as 2.8 million books destroyed.[91]

In 1997 the FR Yugoslavia submitted claims to the International Court of Justice in which it charged that Bosnia and Herzegovina was responsible for the acts of genocide which were committed against the Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, acts which were incited by anti-Serb sentiment and rhetoric which was communicated through all forms of the media. For example, The Novi Vox, a Muslim youth paper, published a poem titled "Patriotic Song" with the following verses: "Dear mother, I'm going to plant willows; We'll hang Serbs from them; Dear mother, I'm going to sharpen knives; We'll soon fill pits again."[92] The paper Zmaj od Bosne published an article with a sentence saying "Each Muslim must name a Serb and take oath to kill him."[92] The radio station Hajat broadcast "public calls for the execution of Serbs."[92]

According to Vojislav Koštunica and British commentator Mary Dejevky, in the summer of 1995 the French president, Jacques Chirac created controversy when he commented on the Bosnian War, he reportedly called Serbs "a nation of robbers and terrorists".[93][94]

During the war in Croatia, French writer Alain Finkielkraut insinuated that Serbs were inherently evil, comparing Serb actions to the Nazis during World War II.[95]

During the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, columnist Thomas Friedman wrote the following in The New York Times on 23 April 1999: "Like it or not, we are at war with the Serbian nation (the Serbs certainly think so), and the stakes have to be very clear: Every week you ravage Kosovo is another decade we will set your country back by pulverizing you. You want 1950? We can do 1950. You want 1389? [referring to the Battle of Kosovo] We can do 1389 too." Friedman urged the US to destroy "in Belgrade: every power grid, water pipe, bridge [and] road", annex Albania and Macedonia as "U.S. protectorates", "occupy the Balkans for years," and "[g]ive war a chance."[96] Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR) labeled Friedman's remarks "war-mongering" and "crude race-hatred and war-crime agitation".[97]

Outside the Balkans, Noam Chomsky observed that not just the government of Serbia, but also the people, were reviled and threatened. He described the jingoism as "a phenomenon I have not seen in my lifetime since the hysteria whipped up about 'the Japs' during World War II".[98] Chomsky made such comments while also denying some aspects of the Bosnian genocide.[99]

Criticism

Some criticism of Anti-Serb sentiment or Serbophobia purportedly corresponds to its interplay with perceived historical revisionism and myths practiced by some Serbian nationalist writers and the government of Slobodan Milošević in the 1990s.[100] According to political scientist David Bruce MacDonald, in the 1980s Serbs increasingly began to compare themselves to Jews as fellow victims in world history, which involved tragedizing historic events, from the 1389 Battle of Kosovo to the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution, as every aspect of history was seen as yet another example of persecution and victimisation of Serbs at the hands of external negative forces.[101] Serbophobia was often likened to antisemitism and expressed itself as a re-analysis of history where every event that had a negative effect on the Serbs was likened to a tragedy, and used to justify territorial expansion into neighbouring regions.[102] According to Christopher Bennett, former director of the International Crisis Group in the Balkans, the idea of historic Serb martyrdom grew out of the thinking and writing of Dobrica Ćosić who developed a complex and paradoxical theory of Serb national persecution, which evolved over two decades between the late 1960s and the late 1980s into the Greater Serbian programme.[103] Serbian nationalist politicians have made associations to Serbian "martyrdom" in history (from the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 to the genocide during World War II) to justify Serbian politics of the 1980s and 1990s.[103] In late 1988, months before the Revolutions of 1989, Milošević accused his critics like the Slovenian leader Milan Kučan of "spreading fear of Serbia" as a political tactic.[104]

Contemporary and recent issues

At a football game between Kosovo and Croatia played in Albania in October 2016, the fans together chanted murderous slogans against Serbs.[105] Both countries face FIFA hearings due to the incident.[106] Croat and Ukrainian sports fans have put up hate messages towards Serbs and Russians during a match of their national teams in the 2018 World Cup qualifier.[107]

Kosovo Albanians

The worst ethnic violence in Kosovo since the end of the 1999 conflict erupted in the partitioned town of Mitrovica, leaving hundreds wounded and at least 14 people dead. UN peacekeepers and NATO troops scrambled to contain a raging gun battle between Serbs and ethnic Albanians.[108] Within hours the province was immersed in anti-Serb and anti-UN rioting and had regressed to levels of violence not seen since 1999. In Serbia the events were also called the March Pogrom (Serbian: Мартовски погром / Martovski pogrom). International courts in Pristina have prosecuted several people who attacked several Serbian Orthodox churches, handing down jail sentences ranging from 21 months to 16 years.[109] Numerous Serbian cultural sites in Kosovo were destroyed during and after the Kosovo War. According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, 155 Serbian Orthodox churches and monasteries were destroyed by Kosovo Albanians between June 1999 and March 2004.[110]

Kosovo Albanian media depict Serbia and Serbs as a threat to state frame and security, as disrupting institutional order, draining resources, being extremists, tied to criminal activities (in North Kosovo), and in retrospect as perpetrators of war crimes and violations of humans rights (reminding the public of Serbs as enemies). Serbs are blamed for inducing the Kosovo War, and since the war are negatively characterized as uncooperative, aggressive, extremist while the Serbian crimes in the war are termed "genocide".[111]

Croatia

Croatian nationalist propaganda, especially the Catholic Church supported groups, often advocates anti-Serb views.[112][113] In 2015 Amnesty International reported that Croatian Serbs continued to face discrimination in public sector employment and the restitution of tenancy rights to social housing vacated during the war.[114] In 2017 they again pointed Serbs faced significant barriers to employment and obstacles to regain their property. Amnesty International also said that right to use minority languages and scripts continued to be politicized and unimplemented in some towns and that heightened nationalist rhetoric and hate speech contributed to growing ethnic intolerance and insecurity.[115] According to the 2018 European Commission against Racism and Intolerance report, racist and intolerant hate speech in public discourse is escalating; and one of the main targets are Serbs.[116]

Croatian usage of the Ustashe salute Za dom spremni, the equivalent of Nazi salute Sieg Heil, is not banned.[117] It is deemed unconstitutional but allowed in "exceptional situations".[118] In 2016, this salute was inscribed on a plaque that was installed near the site of Jasenovac, sparking a reaction from the Serb and Jewish community. It has also been chanted during football matches.[119] Some Croats, including politicians, have attempted to deny and to minimise the magnitude of the genocide perpetrated against Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia.[120] From 2016 to 2019, anti-fascist groups, leaders of Croatia's Serb, Roma and Jewish communities and former top Croat officials boycotted the official state commemoration for the victims of the Jasenovac concentration camp because, as they said, Croatian authorities refused to denounce the Ustasha legacy explicitly and tolerated the downplaying and revitalization of their crimes, which included the equation of these crimes with the communist crimes from 1945.[121][122][123][124][125]

In 2013 it was reported that a group of right-wing extremists had taken over the Croatian Wikipedia, editing mostly articles related to the Ustashe, whitewashing their crimes, and articles targeting Serbs.[126][127] In the same year there were protests in Vukovar against introducing Serbian language and Cyrillic script signs, because according to one organizer there had to be a "sign of respect for the sacrifice Vukovar has made".[128] Later signs with Cyrillic on administrative buildings were destroyed by Croatian veterans.[129] In 2019, Ivan Penava, Mayor of Vukovar, presented the conclusion that conditions have not been met to introduce special rights on the equal use of the Serbian minority's language and script in Vukovar.[130]

Serbian politicians have recently accused Croatian politicians of anti-Serbian sentiment.[131] In its 2016 report on human rights in Croatia, the US State Department warned about pro-Ustashe and anti-Serb sentiment in Croatia.[132] According to the Serbian National Council, hate speech, threats and violence against Serbs rose by 57% in 2016.[133] On 12 February 2018, when Serbian president Vučić was to meet with Croatian government representatives in Zagreb, hundreds of demonstrators chanted the salute Za dom spremni! at the city square.[134]

Marko Perković and band Thompson created controversy by performing songs that openly glorifies the Ustasha regime and the Genocide of Serbs.[135] The band performed Jasenovac i Gradiška Stara, which celebrate the massacres at the Jasenovac and Stara Gradiška, which were among the largest extermination camps in Europe.[136]

In 2019, there were several alleged hate-motivated incidents targeting Serbs in Croatia, including an attack on three VK Crvena zvezda players in the coastal city of Split, an attack on four seasonal workers in the town of Supetar, two of whom were Serbs, singled out by the attackers due to the dialect they were using, and an attack on Serbs who were watching a Red Star Belgrade match.[137] The latter which resulted in injuries to five people, including a minor, resulted in the indictment of 15 men for committing a hate crime.[137]

Montenegro under Milo Đukanović

Some observers have described Milo Đukanović, the longtime ruler of Montenegro, as a Serbophobe.[138][139] Serbs of Montenegro have supposedly been pressured to declare themselves Montenegrins, following the 2006 referendum.[140] [better source needed] The acquisition of Montenegro's independence has renewed the dispute over the ethnic and linguistic identity.[141][142][143][144] Although the majority of citizens in Montenegro declare themselves to speak Serbian language, it is not recognized as an official language.[145] A number of Serbian writers have recently been removed from the school curriculum in Montenegro, which was described as creation of an "anti-Serb atmosphere" by a Serbian MP.[146]

According to the 2017 survey conducted by the Council of Europe in cooperation with the Office of the state ombudsman, 45% of respondents reported experiences of religious discrimination and perception of discrimination were highest by a significant margin among Serbian Orthodox Church members, while Serbs were facing discrimination considerably more than other ethnic communities.[147][148] In June 2019, Mirna Nikčević, first adviser to the Embassy of Montenegro in Turkey, commented on protests in front of the Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ in Podgorica against the announced controversial religious law: "Honestly, I would burn the temple and all the cattle there".[149] A few days later, Zoran Vujović, an actor of the Montenegrin National Theatre, has posted a lot of insults against the Serbs on his Facebook profile, saying that they were "nothingness, ignorant, degenerate, poisonous".[150][151] According to some reporters, pro-Serbian media have faced discrimination.[152]

As of late December 2019, the newly proclaimed religion law or officially Law on Freedom of Religion or Belief and the Legal Status of Religious Communities, which de jure transfers the ownership of church buildings and estates from the Serbian Orthodox Church to the Montenegrin state,[153][154] sparked a series of peaceful nationwide protests which continued to February 2020.[155] The Freedom House described the adoption of the law, which is widely seen to target the Serbian Orthodox Church, as "questionable decision".[156] Eighteen opposition MPs, mostly Serbs, were arrested prior to the voting, under the charge for violently disrupting the vote.[156][157] Some church officials were attacked by the police[158][159] and a number of journalists, opposition activists and protesting citizens were arrested.[160][161][162] President Milo Đukanović called the protesting citizens "a lunatic movement".[163][164][165]

Hate speech and derogatory terms

Among derogatory terms for Serbs are "Vlachs" (Власи / Vlasi) which was used mainly in Hrvatsko Zagorje during rebellion in the early 20th century.[166] and "Chetniks" (четници / četnici) used by Croats and Bosniaks;[167] Shkije by Albanians;[168][169] while Čefurji is used in Slovenia for immigrants from other former Yugoslav republics.[170] In Montenegro, a widely used derogatory term for Serbs is Posrbice (посрбице), and it denotes "Montenegrins who identify as Serbs".[171]

Anti-Serb slogans

The slogan Srbe na vrbe! (Србе на врбе), meaning "Hang Serbs from the willow trees!" (lit. 'Serbs onto willows!') originates from a poem, and was first used by the Slovene politician Marko Natlačen in 1914, at the beginning of the Austro-Hungarian war against Serbia.[172][173] It was popularized before World War II by Mile Budak,[174] the chief architect of Ustaše ideology against Serbs. During World War II there were mass hangings of Serbs in the Independent State of Croatia as part of the Ustaše persecution of the Serbs.

In present-day Croatian nationalists and people who oppose the return of Serb refugees often use the slogan. Graffiti with the phrase is common, and was noted in the press when it was found painted on a church in 2004,[175] 2006,[176] and on another church in 2008.[177] In 2010, a banner displaying the slogan appeared in the midst of tourist season at the entrance to Split, a major tourist hub in Croatia, during a Davis Cup tennis match between the two countries. It was removed by the police within hours,[178] and the banner's creator was later apprehended and charged.[179] A Serbian Orthodox church in Geelong, Australia, was spray-painted with the slogan, along with other neo-Nazi symbols, in 2016.[180]

Gallery

-

Devastated and robbed shops owned by Serbs in Sarajevo during the Anti-Serb pogrom in Sarajevo.

-

Austro-Hungarian soldiers executing Serb civilians during World War I.

-

The remains of Serbs executed by Bulgarian soldiers in the Surdulica massacre during World War I. An estimated 2,000–3,000 Serbian men were killed in the town during the first months of the Bulgarian occupation of southern Serbia.[181]

-

Order for Serbs and Jews to move out of their home in Zagreb, in the Nazi puppet state during World War II. Also, a warning of forcible expulsion for Serbs and Jews who fail to comply.

-

Ruins of the Church of Holy Salvation, Prizren which was built circa 1330 and destroyed during the 2004 unrest in Kosovo.

-

14th-century icon from Our Lady of Ljeviš in Prizren, which was damaged in 2004 by rioters.

See also

- Serbian Question

- Persecution of Eastern Orthodox Christians

- Anti-Serb riots in Sarajevo

- 1991 anti-Serb riot in Zadar

- Panda Bar incident

- Podujevo bus bombing

- Goraždevac murders

- Anti-Slavic sentiment

References

- ^ Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato.

- ^ Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29 (4): 460–461. doi:10.1080/13602000903411366. S2CID 143499467.

- ^ Krakov 1990, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Skendi 2015, p. 293.

- ^ Skendi 2015, p. 201.

- ^ Iain King; Whit Mason (2006). Peace at Any Price: How the World Failed Kosovo. Cornell University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-8014-4539-6.

- ^ Little 2007, p. 125.

- ^ Hadži Vasiljević, Jovan (1928). Četnička akcija u Staroj Srbiji i Maćedoniji. p. 14.

- ^ Kurt Jonassohn; Karin Solveig Björnson (January 1998). Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations: In Comparative Perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-4128-2445-3.

Anti-Serbian sentiment had already been expressed throughout the nineteenth century when Croatian intellectuals began to make plans for their own national state. They viewed the presence of more than one million Serbs in Krajina and Slavonia as intolerable.

- ^ a b Meier 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Carmichael 2012, p. 97

For Starčević ... Serbs were 'unclean race' ... Along with ... Eugen Kvaternik believed that 'there could be no Slovene or Serb people in Croatia because their existence could only be expressed in the right to a separate political territory.

- ^ John B. Allcock; Marko Milivojević; John Joseph Horton (1998). Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-87436-935-9.

Starcevic was extremely anti-Serb, seeing Serb political consciousness as a threat to Croats.

- ^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 3

In polemics of the 1850s, Starčević also coined a misleading term – "Slavoserb", derived from the Latin word "sclavus" and "servus" to denote persons ready to serve foreign rulers against their own people.

- ^ a b Carmichael 2012, p. 97.

- ^ MacDonald 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Gregory C. Ference (2000). "Frank, Josip". In Richard Frucht (ed.). Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism. New York & London: Garland Publishing. pp. 276–277.

- ^ (in Croatian) "Eugen Dido Kvaternik, Sjećanja i zapažanja 1925–1945, Prilozi za hrvatsku povijest.", Dr. Jere Jareb, Starčević, Zagreb, 1995., ISBN 953-96369-0-6, str. 267.: Josip Frank pokršten je, kad je imao 18 godina.

- ^ a b c Trbovich 2008, p. 136.

- ^ Robert A. Kann (1980). A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526–1918. University of California Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-520-04206-3.

in the case of Frank's followers ... strongly anti-Serb

- ^ Stephen Richards Graubard (1999). A New Europe for the Old?. Transaction Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-4128-1617-5.

Under Josip Frank, who carried the rightists into a new era, the party became obsessively anti-Serbian.

- ^ Jelavich & Jelavich 1986, p. 254.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Bilandžić, Dušan (1999). Hrvatska moderna povijest. Golden marketing. p. 31. ISBN 953-6168-50-2.

- ^ a b Ramet 1998, p. 155

Thus, from the mid-nineteenth century until the 1920s, the church in Croatia was riven into two factions: the progressives, who favored the incorporation of Croatia into a liberal Slavic state ... and the conservatives, ... who were loath to bind Catholic Croatia to Orthodox Serbia. ... By 1900 the exclusivist orientation seems to have gained the upper hand in Catholic circles and the First Croatian Catholic Congress, held in Zagreb that year, was implicitly anti-Orthodox and anti-Serb.

- ^ a b Richard C. Frucht (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 644. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

The Balkan Wars left Serbia as the region's strongest power. Serbia's relationship with Austria-Hungary remained antagonistic, and the Habsburg administration in Bosnia-Hercegovina became anti-Serb ... the governor of Bosnia declared state of emergency, dissolved the parliament, ... and closed down many Serb associations ...

- ^ Mitja Velikonja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

The anti-Serb policy and mood that emerged in the months leading up to the First World War were the result of the machinations of Gen. Oskar von Potiorek (1853-1933), Bosnia-Herzegovina's heavy-handed military governor.

- ^ Daniela Gioseffi (1993). On Prejudice: A Global Perspective. Anchor Books. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-385-46938-8.

Andric describes the "Sarajevo frenzy of hate" that erupted among Muslims, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox believers following the assassination on 28 June 1914, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo

- ^ Robert J. Donia (29 June 1914). Sarajevo: A Biography. University of Michigan Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0472115570.

- ^ Joseph Ward Swain (1933). Beginning the Twentieth Century: A History of the Generation That Made the War. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 347.

- ^ John Richard Schindler (1995). A Hopeless Struggle: The Austro-Hungarian Army and Total War, 1914–1918. McMaster University. p. 50. ISBN 978-0612058668.

anti-Serbian demonstrations in Sarajevo, Zagreb and Ragusa.

- ^ Christopher Bennett (January 1995). Yugoslavia's Bloody Collapse: Causes, Course and Consequences. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-85065-232-8.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485.

- ^ Herbert Kröll (2008). Austrian-Greek Encounters Over the Centuries: History, Diplomacy, Politics, Arts, Economics. Studienverlag. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-7065-4526-6.

arrested and interned some 5.500 prominent Serbs and sentenced to death some 460 persons, a new Schutzkorps, an auxiliary militia, widened the anti-Serb repression.

- ^ Klajn 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 94.

- ^ Banac 1988, p. 297.

- ^ Gustav Regler; Gerhard Schmidt-Henkel; Ralph Schock; Günter Scholdt (2007). Werke. Stroemfeld/Roter Stern. p. 46. ISBN 978-3-87877-442-6.

Mit Kreide war an die Waggons geschrieben: »Jeder Schuß ein Russ', jeder Stoß ein Franzos', jeder Tritt ein Brit', alle Serben müssen sterben.« Die Soldaten lachten, als ich die Inschrift laut las. Es war eine Aufforderung, mitzulachen.

- ^ Andrej Mitrović, Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918 pp. 78–79. Purdue University Press, 2007. ISBN 1-55753-477-2, ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4

- ^ Ana S. Trbovich (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0195333435.

- ^ Burgwyn, H. James. Italian foreign policy in the interwar period, 1918–1940. p. 43. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997.

- ^ Sestani, Armando, ed. (10 February 2012). "Il confine orientale: una terra, molti esodi" [The Eastern Border: One Land, Multiple Exoduses]. I profugi istriani, dalmati e fiumani a Lucca [The Istrian, Dalmatian and Rijeka Refugees in Lucca] (PDF) (in Italian). Instituto storico della Resistenca e dell'Età Contemporanea in Provincia di Lucca. pp. 12–13.

When dealing with such a race as Slavic – inferior and barbarian – we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Mussolini, Benito; Child, Richard Washburn; Ascoli, Max; & Lamb, Richard (1988) My rise and fall. New York: Da Capo Press. pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Božić 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Božić 2010, p. 187.

- ^ Božić 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Božić 2010, pp. 203–204.

- ^ United States. Congress. Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (1993). Human Rights and Democratization in Croatia. The Commission. p. 3.

Increasing centralization by Belgrade, however, encouraged anti-Serbian sentiment in Croatia

- ^ The Holocaust and History The Known, the Unknown, the Disputed, and the Reexamined Edited by Michael Berenbaum and Abraham J. Peck, Indiana University Press p. 59 "Pseudoracial policy of Third Reich ... Gypsies, Slavs, blacks, Mischlinge, and Jews are not Aryans."

- ^ Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection Paul R. Bartrop, Steven Leonard Jacobs p. 1160, "This strict dualism between the "racially pure" Aryans and all others—especially Jews and Slavs—led to the radical outlawing of all "non-Aryans" and their eventual enslavement and attempted annihilation"

- ^ Shirer, William L. (1960) The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 937, 939. Quotes: "The Jews and the Slavic people were the Untermenschen – subhumans." (937); "[The] obsession of the Germans with the idea that they were the master race and that Slavic people must be their slaves was especially virulent in regard to Russia. Erich Koch, the roughneck Reich Commissar for the Ukraine, expressed it in a speech at Kyiv on 5 March 1945.

We are the Master Race and must govern hard but just ... I will draw the very last out of this country. I did not come to spread bliss ... The population must work, work, and work again ... We are a master race, which must remember that the lowliest German worker is racially and biologically a thousand times more valuable than the population [of the Ukraine]. (emphasis added)

- ^

Stephen E. Hanson; Willfried Spohn (1995). Can Europe Work?: Germany and the Reconstruction of Postcommunist Societies. University of Washington Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-295-80188-9.

German anti-Serbian sentiment increased after Hitler's ascent to power in 1933. His Serbophobia, which was rooted in the years of his youth which he spent in Vienna, was virulent. As a result, Nazi ideology became permeated with anti-Serbian sentiment.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b Klajn 2007, p. 17.

- ^ "Ustasa (Croatian political movement) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- ^

Tomasevich (2001), p. 391

Serbia proper was under strict German occupation, a situation which allowed the Ustasha to pursue its radical anti-Serbian policy

- ^ Aleksa Djilas (1991). The Contested Country: Yugoslav Unity and Communist Revolution, 1919–1953. Harvard University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-674-16698-1. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

It was racist and genocidal hatred of people who merely had different national consciousness

- ^ Rory Yeomans; Anton Weiss-Wendt (2013). Racial Science in Hitler's New Europe, 1938–1945. University of Nebraska Press. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-8032-4605-8.

The Ustasha regime ... inaugurated the most brutal campaign of mass murder against civilian population that Southern Europe has ever witnessed ... The campaign of mass murder and deportation against the Serb population was initially justified on scientific racist principles.

- ^ Frederick C. DeCoste; Bernard Schwartz (2000). The Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Education; [includes Papers from the Conference, Held at the University of Alberta, Oct. 1997]. University of Alberta. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-88864-337-7.

The new government quickly adopted Nazi-type racial laws and genocidal tactics to deal with Roma, Serbs and Jews, whom these laws termed "aliens outside the national community".

- ^ Adeli, Lisa Marie (2009). Resistance to the Persecution of Ethnic Minorities in Croatia and Bosnia During World War II: Lisa M. Adeli: Books. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0773447455.

- ^ Žerjavić, Vladimir (1993). Yugoslavia – Manipulations With the Number of Second World War Victims. Croatian Information Centre. ISBN 0-919817-32-7.

- ^ Yeomans, Rory (2012). Visions of Annihilation: The Ustasha Regime and the Cultural Politics of Fascism, 1941–1945. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0822977933.

- ^ McAdams, C. Michael (16 August 1992). "Croatia: Myth and Reality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "The Serbs and Croats: So Much in Common, Including Hate, May 16, 1991". The New York Times. 16 May 1991. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Lemkin, Raphael (2008). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Clark, New Jersey: The Lawbook Exchange. pp. 259–264. ISBN 978-1584779018.

- ^ "Genocide of the Serbs". The Combat Genocide Association.

- ^ Levy, Michele Frucht (November 2009). "The Last Bullet for the Last Serb":The Ustaša Genocide against Serbs: 1941–1945". Nationalities Papers. 37 (6): 807–837. doi:10.1080/00905990903239174. S2CID 162231741.

- ^ McCormick, Robert B. (2014). Croatia Under Ante Pavelić: America, the Ustaše and Croatian Genocide. London-New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1780767123.

- ^ Ivo Goldstein. "Uspon i pad NDH". Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2011.

- ^ Samuel Totten, William S. Parsons (1997). Century of Genocide: Critical Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. Taylor & Francis. p. 430. ISBN 0-203-89043-4. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ "SISAK CAMP". Jasenovac Memorial Cite. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Marija Vuselica: Regionen Kroatien in Der Ort des Terrors: Arbeitserziehungslager, Ghettos, Jugendschutzlager, Polizeihaftlager, Sonderlager, Zigeunerlager, Zwangsarbeiterlager, Volume 9 of Der Ort des Terrors, Publisher C.H. Beck, 2009, ISBN 978-3406572388 pp. 321–323

- ^ Anna Maria Grünfelder: Arbeitseinsatz für die Neuordnung Europas: Zivil- und ZwangsarbeiterInnen aus Jugoslawien in der "Ostmark" 1938/41–1945, Publisher Böhlau Verlag Wien, 2010 ISBN 978-3205784531 pp. 101–106

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 124.

- ^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 542

- ^ Tomasevich (2001), p. 391

Close collaboration between Ustaša and part of catholic clergy followed ... above all anti-Serbian ...

- ^ a b Ramet, Sabrina P. (1995). Social currents in Eastern Europe: The sources and consequences of the great transformation. Duke University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0822315483.

- ^ a b Ramet 2006, p. 141.

- ^ a b Yeomans, Rory (2006). "Albania". In Blamires, Cyprian; Jackson, Paul (eds.). World Fascism: A–K. ABC-CLIO. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-5760-7940-9.

- ^ Gerolymatos, Andre (2010). Castles Made of Sand: A Century of Anglo-American Espionage and Intervention in the Middle East. Macmillan. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4299-1372-0.

- ^ Bartrop, Paul R.; Dickerman, Michael (2017). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4408-4084-5.

- ^ Hall, Richard C. (2014). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia. ABC-CLIO. p. 287. ISBN 978-1-6106-9031-7.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the 20th Century. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-1-4422-0665-6.

- ^ Petersen, Hans-Christian; Salzborn, Samuel (2010). Antisemitism in Eastern Europe: History and Present in Comparison. Peter Lang. p. 97. ISBN 978-3-6315-9828-3.

- ^ a b Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A Short History. Macmillan. p. 312. ISBN 978-0333666128.

- ^ Frank, Chaim (2010). Petersen, Hans-Christian; Salzborn, Samuel (eds.). Antisemitism in Eastern Europe: History and Present in Comparison. Bern: Peter Lang. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-3-631-59828-3.

- ^ "SANU". 16 June 2008. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

The present depressing condition of the Serbian nation, with chauvinism and Serbophobia being ever more violently expressed in certain circles, favor of a revival of Serbian nationalism, an increasingly drastic expression of Serbian national sensitivity, and reactions that can be volatile and even dangerous.

- ^ Robert Bideleux; Professor Richard Taylor (2013). European Integration and Disintegration: East and West. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-134-77522-4.

By 1987 accelerating inflation and rapid depreciation of the dinar were strengthening Slovene and Croatian demands for sweeping economic liberalization, but these were blocked by Serbia. This exacerbated the growing anti-Serbian sentiments among non-Serbs, but also enhanced Serbian support for Milošević's nationalism and his manipulation of the Kosovo issue, culminating in the abolition of the autonomy of that region.

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 39.

- ^ Ramet 2007, p. 3

Because of its independence from Belgrade (though not from Berlin) and because of its association with anti-Serb and anti-Allied politics, the NDH would later serve as a rallying symbol for those who wanted to declare their antipathy towards Serbia (during the War of Yugoslav secession)

- ^ Ramet 2006, p. 240

Nationalist and Liberal Echoes in Other Republics Every republic and autonomous province was struck by nationalist outbursts in these years, and among all the non-Serbian nationalities, there were strong anti- Serbian feelings.

- ^ "Lešaja: Devedesetih smo uništili 2,8 mil. 'nepoćudnih' knjiga – Jutarnji List". www.jutarnji.hr. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ a b c International Court of Justice 17 December 1997 Case Concerning Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "'Rude' Chirac ruffles a few feathers". The Independent. 28 June 1995. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "The Serb nation at the crossroads". Peščanik. 2 April 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ MacDonald 2002, p. 267.

- ^ Thomas Friedman (23 April 1999). "Stop the Music". The New York Times.

- ^ "CPJ Declares Open Season on Thomas Friedman". Fair.org. September 2000.

- ^ Gallagher, Tom (5 August 2000). "The Lessons From Kosovo". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2020). "Chomsky and Genocide". Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal. 14 (1): 76–101. doi:10.5038/1911-9933.14.1.1738.

- ^ MacDonald 2002, pp. 63–64, 82–83.

- ^ MacDonald 2002, p. 7.

- ^ MacDonald 2002, pp. 82–88.

- ^ a b Comment: Serbia's War With History Archived 10 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine by C. Bennett, Institute for War & Peace Reporting, 19 April 1999

- ^ "Communism O Nationalism!", Time, 24 October 1988

- ^ "Kosovo-Croatia Match Marred by Anti-Serbian Chants". Balkan Insight.

- ^ "Kosovo & Croatia face Fifa hearings over anti-Serbian chanting". BBC.

- ^ "Croat and Ukrainian fans' hate message to Serbs and Russians". B92. 27 March 2017.

- ^ "Collapse in Kosovo". 22 April 2004. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "Bitter Memories of Kosovo's Deadly March Riots". balkaninsight.com. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Edward Tawil (February 2009). "Property Rights in Kosovo: A Haunting Legacy of a Society in Transition" (PDF). New York: International Center for Transitional Justice. p. 14.

- ^ Zdravković-Zonta Helena (2011). "Serbs as threat the extreme negative portrayal of the Serb "minority" in Albanian-language newspapers in Kosovo". Balcanica (42): 165–215. doi:10.2298/BALC1142165Z.

- ^ Bjelajac, Branko (2015). "Review of Radeljić and Topić's "Religion in the Post-Yugoslav Context"". Serbian Political Thought. 36 (4): 76.

- ^ Bruce Macdonald, David (2002). Balkan Holocausts? Serbian and Croatian Victim-Centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. p. 20. doi:10.7228/manchester/9780719064661.001.0001. ISBN 978-1526137258. JSTOR j.ctt155jbrm.

- ^ "Croatia report". 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ "Croatia 2016/2017report". Retrieved 23 February 2017.

- ^ "ECRI Report on Croatia 2018". Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Kristović, Ivica (22 November 2013). "Pozdrav 'Za dom spremni' ekvivalent je nacističkom 'Sieg Heil!'". Večernji list. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ^ Milekic, Sven (28 February 2018). "Croatian Fascist Slogan Deemed Unconstitutional but Allowable". Balkan Insight. BIRN.

- ^ Milošević, Ana (2020). Europeanisation and Memory Politics in the Western Balkans. Springer Nature. p. 67. ISBN 978-3-03054-700-4.

- ^ Drago Hedl (10 November 2005). "Croatia's Willingness To Tolerate Fascist Legacy Worries Many". BCR Issue 73. IWPR. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ "Dokle će se u Jasenovac u tri kolone?". N1. 23 April 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Jasenovac Camp Victims Commemorated Separately Again". balkaninsight.com. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Jewish and Serbian minorities boycott official "Croatian Auschwitz" commemoration". neweurope.eu. 28 March 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Former top Croat officials join boycott of Jasenovac event". B92. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Vladisavljevic, Anja (22 April 2020). "Croatia Remembers Victims of WWII Jasenovac Camp". Balkan Insight.

- ^ "Hr.wikipedija pod povećalom zbog falsificiranja hrvatske povijesti" [Croatian Wikipedia under a scrutiny for fabricating Croatian history!] (in Croatian). Novi list. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ Sampson, Tim (1 October 2013). "How pro-fascist ideologues are rewriting Croatia's history". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ^ "Thousands of Vukovar Croats rally against Serb Cyrillic signs". Reuters. 2 February 2013.

- ^ "Croatia War Veterans Trash Cyrillic Signs in Vukovar". 2 September 2013.

- ^ "Heated debate on Cyrillic script in Vukovar City Council". Glas Hrvatske. 18 October 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Dacic: "The EU offered no real answer to the anti-Serbian policy in the region"". MFA.

- ^ "Slap for Croats: New report of Americans is warning on praising of Ustasha and Anti-Serb Feelings in Croatia". Telegraf.

- ^ "Intolerance Towards Serbs 'Escalates in Croatia': Report". Balkan Insight. 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Prve Haos U Zagrebu Ustaše skandiraju: "Za dom spremni"". Alo!.

- ^ "Croatia scores own goal after World Cup success". Financial Times. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Zuroff, Efraim (25 June 2007). "Ustasa rock n' roll". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ a b Vladisavljevic, Anja (23 December 2019). "Croatia: 2019 Blighted by Anti-Serb Hatred". BalkanInsight. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network.

- ^ Bieber, Florian (2003). Montenegro in Transition Problems of Identity and Statehood. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-832-90072-4.

- ^ Štavljanin, Dragan (29 February 2008). "Milo Đukanović: Potcijenio sam opasnost od manipulacije narodom". Radio Slobodna Evropa. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Milacic, Slavisha Batko (9 November 2018). "Serbian question in Montenegro". Modern Diplomacy. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ Huszka, Beata (2013). "The Montenegrin independence movement". Secessionist Movements and Ethnic Conflict: Debate-Framing and Rhetoric in Independence Campaigns. Routledge. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-1-134-68784-8.

- ^ Džankić, Jelena (2014). "Reconstructing the Meaning of Being "Montenegrin"". Slavic Review. 73 (2): 347–371. doi:10.5612/slavicreview.73.2.347. hdl:1814/31495. S2CID 145292451.

- ^ Vuković, Ivan (2015). "Population Censuses in Montenegro – A Century of National Identity "Repacking"". Contemporary Southeastern Europe. 2 (2): 126–141.

- ^ Imeri, Shkelzen (2016). "Evolution of National Identity in Montenegro". Slavic Review. 5 (3): 141. doi:10.5901/ajis.2016.v5n3p141.

- ^ "Montenegrin Serbs Allege Language Discriminatio". Balkan Insight. 20 October 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ "CG: U školskoj lektiri nema mjesta za srpske pisce". Region – RTRS. RTRS, Radio Televizija Republike Srpske, Radio Television of Republic of Srpska. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- ^ "Discrimination Patterns in Montenegro". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- ^ "2017 Report on International Religious Freedom: Montenegro". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Stavovi savjetnice nijesu stavovi države CG". RTCG. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Glumac Crnogorskog narodnog pozorišta vređa Srbe za koje kaže da su "ništavila, neznalice, izrodi, smećari" ..." Politika. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Radiosarajevo.ba (21 June 2019). "Crnogorski glumac prvo izvrijeđao pa se izvinio Srbima". Radio Sarajevo. Retrieved 21 June 2019.

- ^ Ђурић, Новица. "Дискриминација српских медија у Црној Гори". Politika Online. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "Serbs Protest in Montenegro Ahead of Vote on Religious Law". The New York Times. Reuters. 26 December 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Montenegro's Attack on Church Property Will Create Lawless Society". Balkan Insight. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Several Thousand Protest Church Bill in Montenegro". The New York Times. Associated Press. 1 January 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Nation in Transit 2020: Montenegro". Freedom House. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Montenegro's parliament approves religion law despite protests". BBC. 27 December 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Episkop Metodije, posle prebijanja u Crnoj Gori, hospitalizovan na VMA". Politika Online. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ "Саопштење ЦО Никшић: Физички нападнут свештеник Мирко Вукотић". slobodnahercegovina.com. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Bivši predsednik opštine Danilovgrad uhapšen na protestu". N1 Srbija (in Serbian (Latin script)). 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Montenegrin Protesters Clash With Police Over Religion Law". The New York Times. Reuters. 30 December 2019. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Marko Milačić uhapšen zbog jučerašnjeg protesta, Carević pozvao građane Budve večeras na protest". Javna medijska ustanova JMU Radio-televizija Vojvodine. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- ^ "Đukanović: "To je ludački pokret", DF: "Mi smo deo tog pokreta"". Independent Balkan News Agency. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Đukanović mirne litije za odbranu svetinja nazvao "ludačkim pokretom koji ruši Crnu Goru"". Sve o Srpskoj (in Serbian). 28 January 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Milo Đukanović nazvao LUDACIMA narod u litijama po Crnoj Gori". www.novosti.rs (in Serbian (Latin script)). Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Banac 1988, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Pål Kolstø (2009). Media Discourse and the Yugoslav Conflicts: Representations of Self and Other. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4094-9164-4.

The hostile 'them' were labelled either as the abstract but omnipresent 'aggressor' or as the stereotypical 'Chetniks' and 'Serbo-communists'. Other derogatory references in Večernji list, ...

- ^ "Civil Rights Defense Minority Communities, March 2006" (PDF). 28 September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ NIN. nedeljne informativne novine. Politika. 2005. p. 6.

Албанци Србе зову Шкије, и то им је сасвим у реду, иако је то исто увредљиво као српски погрдни назив за Албанце

- ^ "Fran/SNB". Fran.

- ^ Ђурић, Новица. "Прогон "посрбица" на "Фејсбуку" у Црној Гори". Politika Online. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Božo Repe (2005). "Slovene History – 20th century, selected articles" (PDF). Department of History of the University of Ljubljana. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "O Mili Budaku, opet: Deset činjenica i deset pitanja – s jednim apelom u zaključku" (in Croatian). Index.hr. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ Vinko Nikolić (1990). Mile Budak, pjesnik i mučenik Hrvatske: spomen-zbornik o stotoj godišnjici rođenja 1899–1989. Hrvatska revija. p. 55. ISBN 978-84-599-4619-3.

gdje je Budak, izgleda po prvi puta, upotrijebio krilaticu «Srbe na vrbe»

- ^ "Ominous Ustashe graffiti on churchyard wall of Church of the Dormition of the Most Holy Mother of God in Imotski". Information Service of the Serbian Orthodox Church. 28 April 2004.[permanent dead link][clarification needed]

- ^ "World Report 2006 – Croatia". Human Rights Watch. January 2006.

- ^ "Uvredljivi grafiti na Pravoslavnoj crkvi u Splitu (Offensive graffiti on the Serbian Orthodox church in Split)" (in Croatian). Nova TV/Dnevnik.hr. 18 January 2008. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "Na ulazu u Split osvanuo sramotni transparent (Shameful banner appears at the entrance to Split)". Jutarnji list (in Croatian). 9 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "Otkriven idejni začetnik izrade rasističkog transparenta – Antonio V. (23) osmislio transparent "Srbe na vrbe"". Večernji list (in Croatian). 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "Geelong church community horrified by anti-Serbian graffiti". SBS. 16 February 2016.

- ^ Mitrović 2007, p. 223.

Sources

- Books

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 978-2825119587.

- Carmichael, Cathie (2012). Ethnic Cleansing in the Balkans: Nationalism and the Destruction of Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-47953-5.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1405142915.

- Ekmečić, Milorad (2000). Srbofobija i antisemitizam. Beli anđeo.

- Klajn, Lajčo (2007). The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga. University Press of America. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7618-3647-6.

- Korb, Alexander (2010). "A Multipronged Attack: Ustaša Persecution of Serbs, Jews, and Roma in Wartime Croatia". Eradicating Differences: The Treatment of Minorities in Nazi-Dominated Europe. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 145–163. ISBN 978-1443824491.

- Krakov, Stanislav (1990) [1930]. Plamen četništva (in Serbian). Belgrade: Hipnos. (in Serbian)

- Jelavich, Charles; Jelavich, Barbara (1986). The Establishment of the Balkan National States, 1804–1920. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-96413-3.

- Jovanović, Batrić (1989). Peta kolona antisrpske koalicije: odgovori autorima Etnogenezofobije i drugih pamfleta. Sloboda. ISBN 9788642100920.

- Little, David (2007). Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85358-3.

- MacDonald, David Bruce (2002). Balkan Holocausts?: Serbian and Croatian Victim Centred Propaganda and the War in Yugoslavia. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-6466-X.

- McCormick, Rob (2008). "The United States' Response to Genocide in the Independent State of Croatia, 1941–1945". Genocide Studies and Prevention. 3 (1): 75–98.

- Meier, Viktor (2013). Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-66511-2.

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-476-7.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2002). Serbia: The History behind the Name. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1850654773.

- Pavlowitch, Stevan K. (2008). Hitler's New Disorder: The Second World War in Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-70050-4.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (1998). Nihil Obstat: Religion, Politics, and Social Change in East-Central Europe and Russia. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2070-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-building and Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8.

- Ramet, Sabrina P. (2007). The Independent State of Croatia 1941-45. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-44055-4.

- Skendi, Stavro (2015). The Albanian National Awakening. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4776-1.

- Štrbac, Savo (2015). Gone with the Storm: A Chronicle of Ethnic Cleansing of Serbs from Croatia. Knin-Banja Luka-Beograd: Grafid, DIC Veritas. ISBN 978-9995589806.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia, 1941–1945: Occupation and Collaboration. Vol. 2. San Francisco: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3615-4.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

- Wingfield, Nancy M., ed. (2003). Creating the Other: Ethnic Conflict & Nationalism in Habsburg Central Europe. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1782388524.

- Journals

- Božić, Sofija (2010). "Serbs in Croatia (1918–1929): Between the myth of "Greater-Serbian Hegemony" and social reality". Balcanica (41): 185–208. doi:10.2298/BALC1041185B.

Further reading

- Антисрпство у уџбеницима историје у Црној Гори (in Serbian). Српско народно вијеће. 2007. ISBN 978-9940-9009-1-5.

- Mitrović, Jeremija D. (2005). Srbofobija i njeni izvori. Službeni glasnik. ISBN 978-8675494232.

- Ћосић, Добрица (2004). Српско питање (in Serbian). Филип Вишњић.

- Popović, Vasilj (1940). Европа и српско питање у периоду ослобођења (1804–1918). Geca Kon.

External links

- Ovey, Michael. "Victim Chic? The Rhetoric of victimhood". Cambridge Papers. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Globalizing the Holocaust: A Jewish "useable past" in Serbian nationalism Archived 9 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine, by David McDonald, University of Otago, New Zealand

- Neue Serbophilie und alte Serbophobie, "New Serbophilia and Old Serbophobia", a 2000 Junge Welt article by Werner Pirker (in German)

- Marc Fumaroli at the Wayback Machine (archive index), a 1999 article by Catherine Argand from Lire, a French literary magazine (in French)

- Europa e nuovi nazionalismi, a 2001 article by Luca Rastello (in Italian)

- Бомбы или гражданская война at the Wayback Machine (archive index), a 2000 Sevodnya article by Alexei Makarkin (in Russian)

- Ku është antimillosheviqi?, a 2000 AIM article by Igor Mekina (in Albanian)

![The remains of Serbs executed by Bulgarian soldiers in the Surdulica massacre during World War I. An estimated 2,000–3,000 Serbian men were killed in the town during the first months of the Bulgarian occupation of southern Serbia.[181]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Ostatky_Srb%C5%AF_povra%C5%BEd%C4%9Bn%C3%BDch_Bulhary.jpg/180px-Ostatky_Srb%C5%AF_povra%C5%BEd%C4%9Bn%C3%BDch_Bulhary.jpg)