Andre Geim

Sir Andre Geim | |

|---|---|

Geim in 2018 | |

| Born |

21 October 1958[3] |

| Nationality | Dutch and British |

| Alma mater | Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology |

| Known for | |

| Spouse | Irina Grigorieva[18][19] |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Condensed matter physics |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Investigation of mechanisms of transport relaxation in metals by a helicon resonance method (1987) |

| Doctoral advisor | Victor Petrashov[4][5] |

| Doctoral students | |

| Website | condmat |

Sir Andre Konstantin Geim FRS HonFRSC HonFInstP (Russian: Андре́й Константи́нович Гейм; born 21 October 1958; IPA1 pronunciation: ɑːndreɪ gaɪm) is a Russian-born Dutch–British physicist working in England in the School of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Manchester.[20]

Geim was awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics jointly with Konstantin Novoselov for his work on graphene.[21][22] He is Regius Professor of Physics and Royal Society Research Professor at the National Graphene Institute. Geim was previously awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2000 for levitating a frog using its intrinsic magnetism. He is the first and only individual, as of 2024, to have received both Nobel and Ig Nobel prizes, for which he holds a Guinness World Record.

Education

[edit]Andre Geim was born to Konstantin Alekseyevich Geim and Nina Nikolayevna Bayer in Sochi, Russia, on 21 October 1958. Both his parents were engineers of German origin; Geim says his maternal great-grandmother was Jewish. [23][24] His grandfather Nikolay N. Bayer (Mykola Baier in Ukrainian) was a notable public figure in Ukraine of the early 20th century, one of its first nature conservationists and the founder/first rector of Kaminiets-Podilskyi University.[25][26]

In 1965, the family moved to Nalchik,[27] where he studied at a high school.[27] After graduation, he applied to the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute.[28] He took the entrance exams twice, but attributes his failure to qualify to discrimination on account of his German ethnicity.[23] He then applied to the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIPT), where he was accepted.

He said that at the time he would not have chosen to study solid-state physics, preferring particle physics or astrophysics, but is now happy with his choice.[29] He received a diplom (MSc degree equivalent) from MIPT in 1982 and a Candidate of Sciences (PhD equivalent) degree in metal physics in 1987 from the Institute of Solid State Physics (ISSP) at the Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS) in Chernogolovka.[29][30]

Academic career

[edit]After earning his PhD with Victor Petrashov,[4] Geim worked as a research scientist at the Institute for Microelectronics Technology (IMT) at RAS, and from 1990 as a post-doctoral fellow at the universities of Nottingham (twice), Bath, and Copenhagen. He said that while at Nottingham he could spend his time on research rather than "swimming through Soviet treacle,"[23] and determined to leave the Soviet Union.[31]

He obtained his first tenured position in 1994, when he was appointed associate professor at Radboud University Nijmegen, where he worked on mesoscopic superconductivity.[32] He later gained Dutch citizenship. One of his doctoral students at Nijmegen was Konstantin Novoselov, who went on to become his main research partner. However, Geim has said that he had an unpleasant time during his academic career in the Netherlands.

He was offered professorships at Nijmegen and Eindhoven, but turned them down as he found the Dutch academic system too hierarchical and full of petty politicking. "This can be pretty unpleasant at times," he says. "It's not like the British system where every staff member is an equal quantity."[31] On the other hand, Geim writes in his Nobel lecture that "the situation was a bit surreal because outside the university walls I received a warm-hearted welcome from everyone around, including Jan Kees and other academics."[33] (Prof. Jan Kees Maan was the research boss of Geim during his time at Radboud University Nijmegen.)

In 2001 he became a professor of physics at the University of Manchester, and was appointed director of the Manchester Centre for Mesoscience and Nanotechnology in 2002. Geim's wife and long-standing co-author, Irina Grigorieva, also moved to Manchester as a lecturer in 2001. The same year, they were joined by Novoselov who moved to Manchester from Nijmegen, which awarded him a PhD in 2004. Geim served as Langworthy Professor between 2007 and 2013, leaving this endowed professorship to Novoselov in 2012.[30] Also, between 2007 and 2010 Geim was an EPSRC Senior Research Fellow before becoming one of Royal Society Research Professors.[30][34]

Geim holds many honorary professorships including those from Tsinghua University (China), Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (Russia), and Radboud University Nijmegen (Netherlands).[35]

Research

[edit]

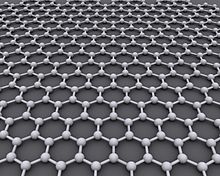

Geim's achievements include the discovery of a simple method for isolating single atomic layers of graphite, known as graphene, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Manchester[36] and IMT. The team published their findings in October 2004 in Science.[37][38][39]

Graphene consists of one-atom-thick layers of carbon atoms arranged in two-dimensional hexagons,[40][41] and is the thinnest material in the world, as well as one of the strongest and hardest.[42] The material has many potential applications.

Geim said one of the first applications of graphene could be in the development of flexible touchscreens, and that he has not patented the material because he would need a specific application and an industrial partner.[43]

Geim also developed a biomimetic adhesive which became known as gecko tape[17]—so called because it works on the same principle as adhesion of gecko feet—research of which is still in the early stages.[44] It is hoped that the development will eventually allow humans to scale ceilings, like Spider-Man.[45]

Geim's research in 1997 into the possible effects of magnetism on water scaling led to the famous discovery of direct diamagnetic levitation of water, and led to a frog being levitated.[46] For this experiment, he and Michael Berry received the 2000 Ig Nobel Prize.[16] "We were asked first whether we dared to accept this prize, and I take pride in our sense of humor and self-deprecation that we did".[23]

Geim has also carried out research on mesoscopic physics and superconductivity.[31][47]

He said of the range of subjects he has studied: "Many people choose a subject for their PhD and then continue the same subject until they retire. I despise this approach. I have changed my subject five times before I got my first tenured position and that helped me to learn different subjects."[29] "When one dares to try, rewards are not guaranteed but at least it is an adventure."[23]

Expanding the scope of his research adventures, Geim started studying low-dimensional water in 2012, after his Nobel-prize achievements. A part of this work was acknowledged by the 2018 Prince Sultan Bin Abdulaziz International Creativity Prize for Water.[48]

He named his favourite hamster, H.A.M.S. ter Tisha, co-author in a 2001 research paper.[37][49]

Honours and awards

[edit]In 2006 he appeared on the Scientific American 50.[50] The Institute of Physics awarded him the 2007 Mott Medal and Prize "for his discovery of a new class of materials—free-standing two-dimensional crystals—in particular graphene".[51] Geim was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 2007.[52] His certificate of election reads:

Geim's research is notable for its internationally-recognised quality, originality and breadth. He has recently discovered a conceptually new class of materials strictly two-dimensional atomic crystals, including graphene. This has opened up a prolific research area including a new paradigm of "relativistic-like condensed matter", where relativistic quantum physics can be studied in a bench-top experiment. Previously, Geim pioneered ballistic Hall micromagnetometry and discovered a paramagnetic Meissner effect and new vortex physics in superconductors. He has also realised a microfabricated adhesive, based on the gecko's climbing mechanism, now being exploited by DuPont, BAe and TESA. His experiments at Nijmegen on magnetic levitation attracted worldwide media attention and stimulated international research in this field. His earlier research on mesoscopic physics included studies of non-local and interaction phenomena, and of the quantum motion of electrons in periodic and random magnetic fields. He disseminates science to the public and schoolchildren through broadcasts and "roadshow" lectures.[52]

He shared the 2008 EPS Europhysics Prize with Novoselov "for discovering and isolating a single free-standing atomic layer of carbon (graphene) and elucidating its remarkable electronic properties".[53] In 2009 he received the Körber European Science Award.[54] The US National Academy of Sciences honoured him with the 2010 John J. Carty Award for the Advancement of Science "for his experimental realisation and investigation of graphene, the two-dimensional form of carbon".[55]

He was awarded one of six Royal Society 2010 Anniversary Research Professorships.[56] The Royal Society added its 2010 Hughes Medal "for his revolutionary discovery of graphene and elucidation of its remarkable properties".[57] He was awarded honorary doctorates from Delft University of Technology,[58] ETH Zürich,[35] the University of Antwerp[59] and the University of Manchester. In 2010, Geim was appointed as Knight Commander of the Order of the Netherlands Lion for his contribution to Dutch Science.[2]

In 2011, Geim became a corresponding member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.[60] He is Honorary Professor of Moscow Phys-Tech, Honorary Professor of the University of Nijmegen, Honorary Fellow of the Institute of Physics (HonFInstP), Honorary Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry (HonFRSC), Honorary Fellow of Singapore Institute of Physics, Honorary Professor of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.[61] Geim was furthermore made a Knight Bachelor in the 2012 New Year Honours for services to science.[62][63] He was elected a foreign associate of the US National Academy of Sciences in May 2012.[64] He was awarded the Copley Medal in 2013 and the Carbon Medal in 2016. Geim received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 2017.[65] In addition to this he also won the 2018 Fray International Sustainability Award given to him by FLOGEN Star Outreach at SIPS 2018 [66]

Ig Nobel Prize in Physics

[edit]

Geim shared the 2000 Ig Nobel Prize in Physics with Sir Michael Berry for the frog experiment. The experiment involved magnetic properties of water scaling to levitate a small frog with magnets,[67] which he and Berry reported in the European Journal of Physics in 1997.[68]

By 2022, his Ig Nobel Prize-winning work on the magnetic levitation of a frog was reportedly part of the inspiration for China's lunar gravity research facility.[69][70]

Nobel Prize in Physics

[edit]

On 5 October 2010, Geim was awarded the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics jointly with Novoselov "for groundbreaking experiments regarding the two-dimensional material graphene".[71] Upon hearing of the award he said, "I'm fine, I slept well. I didn't expect the Nobel Prize this year", and that his plans for the day would not change.[72] The lecture for the award took place on 8 December 2010 at Stockholm University.[73] He said he hopes that graphene and other two-dimensional crystals will change everyday life as plastics did for humanity, although we need to wait for a few decades to see the results.[74]

Mark Miodownik said that his Ig Nobel Prize shows that people can still win a Nobel by "mucking about in a lab".[75] The awards made him the first person to win, as an individual, both a Nobel Prize and an Ig Nobel Prize.[76] On winning both the prizes, he has stated that

"Frankly, I value both my Ig Nobel prize and Nobel prize at the same level and for me Ig Nobel prize was the manifestation that I can take jokes, a little bit of self-deprecation always helps."[4]

2010, Geim was inducted into the Guinness World Records as the "First individual to win both a Nobel and Ig Nobel prize".[77]

Personal life

[edit]View and opinions

[edit]Geim was one of 38 Nobel laureates who signed a declaration in 2010 issued by Scholars for Peace in the Middle East protesting an international initiative to boycott Israeli academics, institutions, and research centers.[78]

At the Nobel Minds symposium in December 2010, Geim said the Nobel Peace Prize committee's choice of Chinese dissident, the imprisoned Liu Xiaobo, as winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, was patronising, saying

"Look at the people who give this Nobel prize. They are retired Norwegian politicians who have spent all their careers in a safe environment, in an oil-rich modern country. They try to extend their views of the world, how the world should work and how democracy works in another country. It's very, very patronising— they have not lived in these countries. In the past 10 years, China has developed not only economically, but even the strongest human rights supporter would agree also human rights have improved. Why do we need to distort this?"[79][80]

Geim has written several opinion pieces for The Financial Times, examples of which can be found on his university webpage.[81]

In 2014, Geim's interview for Desert Island Discs, a popular BBC radio programme, revealed details of his personal life and taste in music.[82]

A quote from Geim was deliberately doctored by the campaign group Vote Leave in the run-up to the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum. An open letter about science, signed by 13 Conservative MPs including Boris Johnson, attempted to paint European science funding as unnecessarily bureaucratic and deliberately misrepresented Geim's views on Europe:

As the Nobel Prize winner Andre Geim said: 'I can offer no nice words for the EU framework programmes [for research] which ... can be praised only by Europhobes for discrediting the whole idea of an effectively working Europe.'

The ellipsis (...) present in the quotation from Geim's Nobel lecture removed the words "except for the European Research Council".[83]

Identity

[edit]Geim has a complex ancestry which is described in detail in his Nobel Prize autobiography.[23] There, Geim stated that most of his family are ethnic Germans, his father descended from Volga Germans and his mother mostly an ethnic German as well. Both his father and paternal grandfather had spent many years of their lives as prisoners in Siberia in Stalin's Gulags, and "some of the family had been prisoners in German concentration camps". He also states that he "suffered from anti-Semitism in Russia because my name sounds Jewish".[84]

Geim summarises his identity as follows. "To the best of my knowledge, the only Jew in the family was my great-grandmother, with the rest on both sides being German. Having lived and worked in several European countries, I consider myself European and do not believe that any further taxonomy is necessary, especially in such a fluid world as the world of science."[23][85]

References

[edit]- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010". Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ a b "Hoge Koninklijke onderscheiding voor Nobelprijswinnaars" (in Dutch). Public Information Service of the Government of the Netherlands. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2013.

- ^ a b "GEIM, Sir Andre (Konstantin)". Who's Who. Vol. 2014 (online edition via Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d "BBC Radio 4 – Andre Geim Profile by Helen Grady, first broadcast 27 July 2013".

- ^ "Mentor of two Nobel Prize winners teaches at Royal Holloway". Archived from the original on 31 July 2013.

- ^ Neubeck, Soeren (2010). Scanning probe investigations on graphene (PhD thesis). University of Manchester.

- ^ Novoselov, Konstantin S. (2004). Development and applications of mesoscopic hall microprobes (PhD thesis). Radboud University Nijmegen. ISBN 9090183663

- ^ Jalil, Rashid (2012). Novel Substrates for Graphene based Electronics (PhD thesis). University of Manchester.

- ^ Jiang, Da (2006). Fabrication, characterization and measurement of atomically thin carbon devices (PhD thesis). University of Manchester. OCLC 643390338.

- ^ Raveendran-Nair, Rahul (2010). Atomic structure and properties of graphene and novel graphene derivatives (PhD thesis). University of Manchester.

- ^ Riaz, Ibtsam (2012). Graphene and Boron Nitride : Members of Two Dimensional Material Family (PhD thesis). University of Manchester.

- ^ Young, Gareth (2005). Investigation into the ferromagnetic properties of graphite (PhD thesis). University of Manchester. OCLC 643421462.

- ^ Geim, A. K.; Kim, P. (2008). "Carbon Wonderland". Scientific American. 298 (4): 90–97. Bibcode:2008SciAm.298d..90G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0408-90. PMID 18380146.

- ^ Geim, A. K.; MacDonald, A. H. (2007). "Graphene: Exploring Carbon Flatland" (PDF). Physics Today. 60 (8): 35. Bibcode:2007PhT....60h..35G. doi:10.1063/1.2774096. S2CID 123480416.

- ^ Novoselov, K. S.; Geim, A. K.; Morozov, S. V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S. V.; Grigorieva, I. V.; Firsov, A. A. (2004). "Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films" (PDF). Science. 306 (5696): 666–669. arXiv:cond-mat/0410550. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..666N. doi:10.1126/science.1102896. PMID 15499015. S2CID 5729649.

- ^ a b Berry, M. V.; Geim, A. K. (1997). "Of flying frogs and levitrons" (PDF). European Journal of Physics. 18 (4): 307. Bibcode:1997EJPh...18..307B. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/18/4/012. S2CID 250889203.

- ^ a b c Geim, A. K.; Dubonos, S. V.; Grigorieva, I. V.; Novoselov, K. S.; Zhukov, A. A.; Shapoval, S. Y. (2003). "Microfabricated adhesive mimicking gecko foot-hair" (PDF). Nature Materials. 2 (7): 461–463. Bibcode:2003NatMa...2..461G. doi:10.1038/nmat917. PMID 12776092. S2CID 19995111.

- ^ "BBC iPlayer – Beautiful Minds: Series 2: Professor Andre Geim". Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Dr Irina V. Grigorieva, research profile – personal details (The University of Manchester)". Archived from the original on 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Professor Andre Geim, FRS (Condensed Matter Physics Group – The University of Manchester)". Archived from the original on 23 April 2012.

- ^ Geim, A. K. (2009). "Graphene: Status and Prospects". Science. 324 (5934): 1530–1534. arXiv:0906.3799. Bibcode:2009Sci...324.1530G. doi:10.1126/science.1158877. PMID 19541989. S2CID 206513254.

- ^ Geim, A. K.; Novoselov, K. S. (2007). "The rise of graphene". Nature Materials. 6 (3): 183–191. arXiv:cond-mat/0702595. Bibcode:2007NatMa...6..183G. doi:10.1038/nmat1849. PMID 17330084. S2CID 14647602.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Andre Geim – Biographical". nobelprize.org. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ "RG-RB – 42". Rg-rb.de. Retrieved 30 October 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Baier, Mykola; Oleksii, Vasyliuk (8 November 2019). Lets respect and protect our native land. figshare. doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.10271936.v1.

- ^ Wikipedia page in Ukrainian: Баєр Микола Миколайович

- ^ a b "Andre Geim, a German Russian, is Awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics". Germans from Russia Heritage Collection (Press release). North Dakota State University. October 2010. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Знай наших: лауреатом Нобелевской премии по физике стал российский немец" [Know our people: a Russian German won the Nobel Prize in Physics]. rusdeutsch.ru (in Russian). 6 October 2010. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Murphy, John (15 July 2006). "Renaissance scientist with fund of ideas". Scientific Computing World. Retrieved 27 October 2010.

- ^ a b c Geim's CV

DOC (56.5 KB). University of Manchester. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

DOC (56.5 KB). University of Manchester. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b c "A physicist of many talents". Physics World. February 2006. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Geim, A.; Dubonos, S.; Palacios, J.; Grigorieva I. V., I.; Henini, M.; Schermer, J. (2000). "Fine Structure in Magnetization of Individual Fluxoid States". Physical Review Letters. 85 (7): 1528–1531. arXiv:cond-mat/0001129. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.1528G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.1528. PMID 10970546. S2CID 46281431.

- ^ Nobel lecture http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2010/geim_lecture.pdf

- ^ "Grants awarded to Andre Geim by the EPRSC". Archived from the original on 13 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Discoverer of graphene back at Radboud University as professor"[permanent dead link]. Radboud University Nijmegen. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "The Story of Graphene". The University of Manchester. 10 September 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b (October 2009). "22 October 2004: Discovery of Graphene". (2.14 MB). APS News (American Physical Society) 18 (9): 2. See the online version here [1].

- ^ "Radical fabric is one atom thick". BBC News. 22 October 2004. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Novoselov, K. S.; Geim, A. K.; Morozov, S. V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S. V.; Grigorieva, I. V.; Firsov, A. A. (2004). "Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films" (PDF). Science. 306 (5696): 666–669. arXiv:cond-mat/0410550. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..666N. doi:10.1126/science.1102896. PMID 15499015. S2CID 5729649.

- ^ Sanderson, K. (2007). "Carbon makes super-tough paper". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news070723-7.

- ^ Palmer, Jason. "Bendy gadget future for graphene". BBC News. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (5 October 2010). "Physics Nobel Honors Work on Ultra-Thin Carbon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Brumfiel, G. (2010). "Andre Geim: In praise of graphene". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.525.

- ^ Black, Richard. "Gecko inspires sticky tape". BBC News. 1 June 2003. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Highfield, Roger. "Gecko lizards inspire 'Spiderman gloves'". The Daily Telegraph. 23 January 2008. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "The Frog That Learned to Fly". Radboud University Nijmegen. Retrieved 19 October 2010. For Geim's account of diamagnetic levitation, see Geim, Andrey. Geim, Andrey (September 1998). "Everyone's Magnetism" (PDF). Physics Today. 51 (9): 36–39. Bibcode:1998PhT....51i..36G. doi:10.1063/1.882437.

- ^ Geim, A. K.; Grigorieva, I. V.; Dubonos, S. V.; Lok, J. G. S.; Maan, J. C.; Filippov, A. E.; Peeters, F. M. (1997). "Phase transitions in individual sub-micrometre superconductors". Nature. 390 (6657): 259. Bibcode:1997Natur.390..259G. doi:10.1038/36797. S2CID 4418440.

- ^ Announcement. "PSIPW". www.psipw.org. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Geim, A. K.; Ter Tisha, H. A. M. S. (2001). "Detection of earth rotation with a diamagnetically levitating gyroscope" (PDF). Physica B: Condensed Matter. 294–295: 736–739. Bibcode:2001PhyB..294..736G. doi:10.1016/S0921-4526(00)00753-5. hdl:10498/19331.

- ^ "Scientific American 50: SA 50 Winners and Contributors". Scientific American. 12 November 2006. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "2007 Mott medal and prize". Institute of Physics. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ a b "Certificate of Election: EC/2007/16: Andre Geim". London: The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019.

- ^ Johnston, Hamish. "Graphene pioneers bag Europhysics prize" Archived 29 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Physics World. 2 September 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "Graphene pioneer wins major international prize". University of Manchester. 21 April 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "John J. Carty Award for the Advancement of Science" Archived 29 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. United States National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Top researchers receive Royal Society 2010 Anniversary Professorships" Archived 8 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Society. 16 October 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "The Hughes Medal (1902)". Royal Society. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "TU Delft honorary doctorate Geim wins Nobel Prize for graphene research"[permanent dead link]. Delft University of Technology. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- ^ "Prizes and awards" Archived 6 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. University of Antwerp. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Andre Geim". Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ^ "(IUCr) A. Geim". iucr.org.

- ^ "No. 60009". The London Gazette (Supplement). 31 December 2011. p. 1.

- ^ "Knighthoods for Nobel-winning graphene pioneers". BBC News. 31 December 2011.

- ^ "National Academy of Sciences Members and Foreign Associates Elected". National Academy of Sciences. 1 May 2012. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Andre Geim winner of the Fray Award".

- ^ "Winners of the Ig Nobel Prize". Ig Nobel Prize. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Berry, M. V.; Geim, A. K. (1997). "Of flying frogs and levitrons". European Journal of Physics. 18 (4): 307. Bibcode:1997EJPh...18..307B. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/18/4/012. ISSN 0143-0807. S2CID 1499061.

- ^ "China building "Artificial Moon" that simulates low gravity with magnets". Futurism.com. Recurrent Ventures. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

Interestingly, the facility was partly inspired by previous research conducted by Russian physicist Andrew Geim in which he floated a frog with a magnet. The experiment earned Geim the Ig Nobel Prize in Physics, a satirical award given to unusual scientific research. It's cool that a quirky experiment involving floating a frog could lead to something approaching an honest-to-God antigravity chamber.

- ^ Stephen Chen (12 January 2022). "China has built an artificial moon that simulates low-gravity conditions on Earth". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 17 January 2022.

It is said to be the first of its kind and could play a key role in the country's future lunar missions. Landscape is supported by a magnetic field and was inspired by experiments to levitate a frog.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 2010". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 26 October 2010. For a video of the announcement, see "Announcement of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 26 October 2010. For the interview with Geim following the award, see "Telephone interview with Andre Geim". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ "Materials breakthrough wins Nobel". BBC News. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "Nobel Lecture". Nobel Prize. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ "Research into graphene wins Nobel Prize". CNN. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Alleyne, Richard. "'Mucking about' with pencil lead and sticky tape wins Nobel Prize for Physics". The Daily Telegraph. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2010.

- ^ "Geim becomes first Nobel & Ig Nobel winner". Improbable Research. 5 October 2010. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ "First individual to win both a Nobel and Ig Nobel prize". Guinness World Records. Retrieved 15 September 2023.

- ^ Statement. Scholars for Peace in the Middle East. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "2010 Nobel Minds". nobelprize.org. Passage begins at about 19:00. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ Bannerman, Lucy. "Liu Xiaobo wrong man for Nobel Peace Prize, say laureates". The Australian. 13 December 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ www

.condmat .physics .manchester .ac .uk /people /academic /geim / - ^ www

.bbc .co .uk /radio4 /features /desert-island-discs /castaway /20e3bf76 #b03z3l2g - ^ "Dominic Cummings' science obsession: based on fact or fiction?". Times Higher Education (THE). 16 October 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Weinreb, Gali (16 November 2010). "Nobel Laureate Geim: Life sciences suited for small countries". Globes. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "Nobel laureate: Life sciences suited to small countries". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com.

Further reading

[edit]- "Documents at the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology" (in Russian). Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- Geim's Nobel Prize banquet speech

- Publications at Astrophysics Data System, NASA

- Selected research papers by Andre Geim's group

- Selected research papers by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov related to research that won them the Nobel Prize

External links

[edit]- Andre Geim on Nobelprize.org

- 1958 births

- 20th-century Dutch physicists

- 20th-century Russian physicists

- 21st-century British inventors

- 21st-century British physicists

- 21st-century Dutch inventors

- Academics of the University of Manchester

- British nanotechnologists

- British Nobel laureates

- Commanders of the Order of the Netherlands Lion

- Carbon scientists

- Dutch nanotechnologists

- Dutch Nobel laureates

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Graphene

- Honorary Fellows of the Institute of Physics

- Ig Nobel laureates

- Knights Bachelor

- Living people

- Magnetic levitation

- Members of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology alumni

- Naturalised citizens of the Netherlands

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- People from Sochi

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Russian emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Russian people of German descent

- Russian scientists

- People associated with the Department of Computer Science, University of Manchester

- Academic staff of Radboud University Nijmegen