And did those feet in ancient time

| And did those feet in ancient time | |

|---|---|

| by William Blake | |

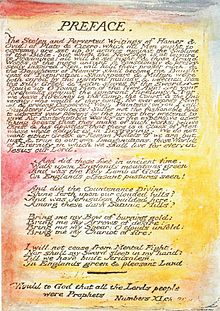

The preface to Milton, as it appeared in Blake's own illuminated version | |

| Written | 1804 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Form | Epic poetry |

| Publication date | 1808 |

| Lines | 16 |

| Full text | |

"And did those feet in ancient time" is a poem by William Blake from the preface to his epic Milton: A Poem in Two Books, one of a collection of writings known as the Prophetic Books. The date of 1804 on the title page is probably when the plates were begun, but the poem was printed c. 1808.[1] Today it is best known as the hymn "Jerusalem", with music written by Sir Hubert Parry in 1916. The famous orchestration was written by Sir Edward Elgar. It is not to be confused with another poem, much longer and larger in scope and also by Blake, called Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion.

It is often assumed that the poem was inspired by the apocryphal story that a young Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, a tin merchant, travelled to what is now England and visited Glastonbury during his unknown years.[2] However, according to British folklore scholar A. W. Smith, "there was little reason to believe that an oral tradition concerning a visit made by Jesus to Britain existed before the early part of the twentieth century".[3] Instead, the poem draws on an older story, repeated in Milton's History of Britain, that Joseph of Arimathea, alone, travelled to preach to the ancient Britons after the death of Jesus.[4] The poem's theme is linked to the Book of Revelation (3:12 and 21:2) describing a Second Coming, wherein Jesus establishes a New Jerusalem. Churches in general, and the Church of England in particular, have long used Jerusalem as a metaphor for Heaven, a place of universal love and peace.[a]

In the most common interpretation of the poem, Blake asks whether a visit by Jesus briefly created heaven in England, in contrast to the "dark Satanic Mills" of the Industrial Revolution. Blake's poem asks four questions rather than asserting the historical truth of Christ's visit.[5][6] The second verse is interpreted as an exhortation to create an ideal society in England, whether or not there was a divine visit.[7][8]

Text

[edit]The original text is found in the preface Blake wrote for inclusion with Milton, a Poem, following the lines beginning "The Stolen and Perverted Writings of Homer & Ovid: of Plato & Cicero, which all Men ought to contemn: ..."[9]

Blake's poem

And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon Englands[b] mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these[c] dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

Beneath the poem Blake inscribed a quotation from the Bible:[10]

"Dark Satanic Mills"

[edit]

The phrase "dark Satanic Mills", which entered the English language from this poem, is often interpreted as referring to the early Industrial Revolution and its destruction of nature and human relationships.[11] That view has been linked to the fate of the Albion Flour Mills in Southwark, the first major factory in London. The rotary steam-powered flour mill, built by Matthew Boulton, assisted by James Watt, could produce 6,000 bushels of flour per week. The factory could have driven independent traditional millers out of business, but it was destroyed in 1791 by fire. There were rumours of arson, but the most likely cause was a bearing that overheated due to poor maintenance.[12]

London's independent millers celebrated, with placards reading, "Success to the mills of Albion but no Albion Mills."[13] Opponents referred to the factory as satanic, and accused its owners of adulterating flour and using cheap imports at the expense of British producers. A contemporary illustration of the fire shows a devil squatting on the building.[14] The mill was a short distance from Blake's home.

Blake's phrase resonates with a broader theme in his works; what he envisioned as a physically and spiritually repressive ideology based on a quantified reality. Blake saw the cotton mills and collieries of the period as a mechanism for the enslavement of millions, but the concepts underpinning the works had a wider application:[15][16]

And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion./...[e]

— Jerusalem Chapter 3. William Blake

Another interpretation is that the phrase refers to the established Church of England, which, in contrast to Blake, preached a doctrine of conformity to the established social order and class system. Stonehenge and other megaliths are featured in Milton, suggesting they may relate to the oppressive power of priestcraft in general. Peter Porter observed that many scholars argue that the "[mills] are churches and not the factories of the Industrial Revolution everyone else takes them for".[17] In 2007, the Bishop of Durham, N. T. Wright, explicitly recognised that element of English subculture when he acknowledged the view that "dark satanic mills" could refer to the "great churches".[18] In similar vein, in 1967 the critic F. W. Bateson stated "the adoption by the Churches and women's organizations of this anti-clerical paean of free love is amusing evidence of the carelessness with which poetry is read".[19]

An alternative theory is that Blake is referring to a mystical concept within his own mythology, related to the ancient history of England. Satan's "mills" are referred to repeatedly in the main poem, and are first described in words which suggest neither industrialism nor ancient megaliths, but rather something more abstract: "the starry Mills of Satan/ Are built beneath the earth and waters of the Mundane Shell...To Mortals thy Mills seem everything, and the Harrow of Shaddai / A scheme of human conduct invisible and incomprehensible".[20]

"Chariots of fire"

[edit]The line from the poem "Bring me my Chariot of fire!" draws on the story of 2 Kings 2:11, where the Old Testament prophet Elijah is taken directly to heaven: "And it came to pass, as they still went on, and talked, that, behold, there appeared a chariot of fire, and horses of fire, and parted them both asunder; and Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven." The phrase has become a byword for divine energy, and inspired the title of the 1981 film Chariots of Fire, in which the hymn "Jerusalem" is sung during the final scenes. The plural phrase "chariots of fire" refers to 2 Kings 6:17.

"Green and pleasant land"

[edit]Blake lived in London for most of his life, but wrote much of Milton while living in a cottage, now Blake’s Cottage, in the village of Felpham in Sussex. Amanda Gilroy argues that the poem is informed by Blake's "evident pleasure" in the Felpham countryside.[21] However, local people say that records from Lavant, near Chichester, state that Blake wrote "And did those feet in ancient time" in an east-facing alcove of the Earl of March public house.[22][23]

The phrase "green and pleasant land" has become a common term for an identifiably English landscape or society. It appears as a headline, title or sub-title in numerous articles and books. Sometimes it refers, whether with appreciation, nostalgia or critical analysis, to idyllic or enigmatic aspects of the English countryside.[24] In other contexts it can suggest the perceived habits and aspirations of rural middle-class life.[25] Sometimes it is used ironically,[26] e.g. in the Dire Straits song "Iron Hand".

Revolution

[edit]Several of Blake's poems and paintings express a notion of universal humanity: "As all men are alike (tho' infinitely various)". He retained an active interest in social and political events for all his life, but was often forced to resort to cloaking social idealism and political statements in Protestant mystical allegory. Even though the poem was written during the Napoleonic Wars, Blake was an outspoken supporter of the French Revolution, and Napoleon claimed to be continuing this revolution.[27] The poem expressed his desire for radical change without overt sedition. In 1803 Blake was charged at Chichester with high treason for having "uttered seditious and treasonable expressions", but was acquitted. The trial was not a direct result of anything he had written, but comments he had made in conversation, including "Damn the King!".[28]

The poem is followed in the preface by a quotation from Numbers 11:29: "Would to God that all the Lords people were prophets." Christopher Rowland has argued that this includes

everyone in the task of speaking out about what they saw. Prophecy for Blake, however, was not a prediction of the end of the world, but telling the truth as best a person can about what he or she sees, fortified by insight and an "honest persuasion" that with personal struggle, things could be improved. A human being observes, is indignant and speaks out: it's a basic political maxim which is necessary for any age. Blake wanted to stir people from their intellectual slumbers, and the daily grind of their toil, to see that they were captivated in the grip of a culture which kept them thinking in ways which served the interests of the powerful.[8]

The words of the poem "stress the importance of people taking responsibility for change and building a better society 'in Englands green and pleasant land.'"[8]

Popularisation

[edit]The poem, which was little known during the century which followed its writing,[29] was included in the patriotic anthology of verse The Spirit of Man, edited by the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Robert Bridges, and published in 1916, at a time when morale had begun to decline because of the high number of casualties in World War I and the perception that there was no end in sight.[30]

Under these circumstances, Bridges, finding the poem an appropriate hymn text to "brace the spirit of the nation [to] accept with cheerfulness all the sacrifices necessary,"[31] asked Sir Hubert Parry to put it to music for a Fight for Right campaign meeting in London's Queen's Hall. Bridges asked Parry to supply "suitable, simple music to Blake's stanzas – music that an audience could take up and join in", and added that, if Parry could not do it himself, he might delegate the task to George Butterworth.[32]

The poem's idealistic theme or subtext accounts for its popularity across much of the political spectrum. It was used as a campaign slogan by the Labour Party in the 1945 general election; Clement Attlee said they would build "a new Jerusalem".[33] It has been sung at conferences of the Conservative Party, at the Glee Club of the British Liberal Assembly, the Labour Party and by the Liberal Democrats.[34]

Setting to music

[edit]By Hubert Parry

[edit]| "Jerusalem" | |

|---|---|

| Anthem by Hubert Parry | |

The composer, c. 1916 | |

| Key | D major |

| Text | "And did those feet in ancient time" by William Blake (1804) |

| Language | English |

| Composed | 10 March 1916 |

| Duration | 2:45 |

| Scoring | |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 28 March 1916 |

| Location | Queen's Hall, Langham Place, London |

| Conductor | Hubert Parry |

| Audio sample | |

Parry’s arrangement rendered electronically | |

In adapting Blake's poem as a unison song, Parry deployed a two-stanza format, each taking up eight lines of Blake's original poem. He added a four-bar musical introduction to each verse and a coda, echoing melodic motifs of the song. The word "those" was substituted for "these" before "dark satanic mills".

Parry was initially reluctant to supply music for the campaign meeting, as he had doubts about the ultra-patriotism of Fight for Right; but knowing that his former student Walford Davies was to conduct the performance, and not wanting to disappoint either Robert Bridges or Davies, he agreed, writing it on 10 March 1916, and handing the manuscript to Davies with the comment, "Here's a tune for you, old chap. Do what you like with it."[35] Davies later recalled,

We looked at [the manuscript] together in his room at the Royal College of Music, and I recall vividly his unwonted happiness over it ... He ceased to speak, and put his finger on the note D in the second stanza where the words 'O clouds unfold' break his rhythm. I do not think any word passed about it, yet he made it perfectly clear that this was the one note and one moment of the song which he treasured ...[36]

Davies arranged for the vocal score to be published by Curwen in time for the concert at the Queen's Hall on 28 March and began rehearsing it.[37] It was a success and was taken up generally.

But Parry began to have misgivings again about Fight for Right, and in May 1917 wrote to the organisation's founder Sir Francis Younghusband withdrawing his support entirely. There was even concern that the composer might withdraw the song from all public use, but the situation was saved by Millicent Fawcett of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). The song had been taken up by the Suffragists in 1917 and Fawcett asked Parry if it might be used at a Suffrage Demonstration Concert on 13 March 1918. Parry was delighted and orchestrated the piece for the concert (it had originally been for voices and organ). After the concert, Fawcett asked the composer if it might become the Women Voters' Hymn. Parry wrote back, "I wish indeed it might become the Women Voters' hymn, as you suggest. People seem to enjoy singing it. And having the vote ought to diffuse a good deal of joy too. So they would combine happily".[36]

Accordingly, he assigned the copyright to the NUWSS. When that organisation was wound up in 1928, Parry's executors reassigned the copyright to the Women's Institutes, where it remained until it entered the public domain in 1968.[36]

The song was first called "And Did Those Feet in Ancient Time" and the early scores have this title. The change to "Jerusalem" seems to have been made about the time of the 1918 Suffrage Demonstration Concert, perhaps when the orchestral score was published (Parry's manuscript of the orchestral score has the old title crossed out and "Jerusalem" inserted in a different hand).[38] However, Parry always referred to it by its first title. He had originally intended the first verse to be sung by a solo female voice (this is marked in the score), but this is rare in contemporary performances. Sir Edward Elgar re-scored the work for very large orchestra in 1922 for use at the Leeds Festival.[39] Elgar's orchestration has overshadowed Parry's own, primarily because it is the version usually used now for the Last Night of the Proms (though Sir Malcolm Sargent, who introduced it to that event in the 1950s, always used Parry's version).

By Wallen

[edit]In 2020 a new musical arrangement of the poem by Errollyn Wallen, a British composer born in Belize, was sung by South African soprano Golda Schultz at the Last Night of the Proms. Parry's version was traditionally sung at the Last Night, with Elgar's orchestration; the new version, with different rhythms, dissonance, and reference to the blues, caused much controversy.[4]

Use as a hymn

[edit]Although Parry composed the music as a unison song, many churches have adopted "Jerusalem" as a four-part hymn; a number of English entities, including the BBC, the Crown, cathedrals, churches, and chapels regularly use it as an office or recessional hymn on Saint George's Day.[40][citation needed]

However, some clergy in the Church of England, according to the BBC TV programme Jerusalem: An Anthem for England, have said that the song is not technically a hymn as it is not a prayer to God;[41] consequently, it is not sung in some churches in England.[42] It was sung as a hymn during the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton in Westminster Abbey.[43]

Many schools use the song, especially public schools in Great Britain (it was used as the title music for the BBC's 1979 series Public School about Radley College), and several private schools in Australia, New Zealand, New England and Canada. In Hong Kong, diverted version of "Jerusalem" is also used as the school hymn of St. Catherine's School for Girls, Kwun Tong and Bishop Hall Jubilee School. "Jerusalem" was chosen as the opening hymn for the London Olympics 2012, although "God Save the Queen" was the anthem sung during the raising of the flag in salute to the Queen. Some attempts have also been made to increase its use elsewhere with other words; examples include the state funeral of President Ronald Reagan in Washington National Cathedral on 11 June 2004, and the state memorial service for Australian Prime Minister Gough Whitlam on 5 November 2014.[citation needed]

It has been sung on BBC's Songs Of Praise for many years; in a countrywide poll to find the UK's favourite hymn in 2019, it was voted top, relegating previous favourite "How Great Thou Art" into second place.

Proposal as English anthem

[edit]Upon hearing the orchestral version for the first time, King George V said that he preferred "Jerusalem" over the British national anthem "God Save the King". "Jerusalem" is considered to be England's most popular patriotic song; The New York Times said it was "fast becoming an alternative national anthem,"[44] and there have been calls to give it official status.[45] England has no official anthem and uses the British national anthem "God Save the King", also unofficial, for some national occasions, such as before English international football matches. However, some sports, including rugby league, use "Jerusalem" as the English anthem. "Jerusalem" is the official hymn of the England and Wales Cricket Board,[46] although "God Save the Queen" has been sung before England's games on several occasions, including the 2010 ICC World Twenty20, the 2010–11 Ashes series and the 2019 ICC Cricket World Cup. Questions in Parliament have not clarified the situation, as answers from the relevant minister say that since there is no official national anthem, each sport must make its own decision.

As Parliament has not clarified the situation, Team England, the English Commonwealth team, held a public poll in 2010 to decide which anthem should be played at medal ceremonies to celebrate an English win at the Commonwealth Games. "Jerusalem" was selected by 52% of voters over "Land of Hope and Glory" (used since 1930) and "God Save the Queen".[47]

In 2005 BBC Four produced Jerusalem: An Anthem For England highlighting the usages of the song/poem and a case was made for its adoption as the national anthem of England. Varied contributions come from Howard Goodall, Billy Bragg, Garry Bushell, Lord Hattersley, Ann Widdecombe and David Mellor, war proponents, war opponents, suffragettes, trade unionists, public schoolboys, the Conservatives, the Labour Party, football supporters, the British National Party, the Women's Institute, London Gay Men's Chorus, London Community Gospel Choir, Fat Les and naturists.[48][49]

Cultural significance

[edit]Enduring popularity

[edit]The popularity of Parry's setting has resulted in many hundreds of recordings being made, too numerous to list, of both traditional choral performances and new interpretations by popular music artists. The song has also had a large cultural impact in Great Britain. It is sung every year by an audience of thousands at the end of the Last Night of the Proms in the Royal Albert Hall and simultaneously in the Proms in the Park venues throughout the country. Similarly, along with "The Red Flag", it is sung each year at the closing of the annual Labour Party conference.

The song was used by the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies (indeed Parry transferred the copyright to the NUWSS in 1918; the Union was wound up in 1928 after women won the right to vote).[50] During the 1920s many Women's Institutes (WI) started closing meetings by singing it, and this caught on nationally. Although it was never adopted as the WI's official anthem, in practice it holds that position, and is an enduring element of the public image of the WI.[51]

A rendition of "Jerusalem" was included in the 1973 album Brain Salad Surgery by the progressive rock group Emerson, Lake & Palmer. The arrangement of the hymn is notable for its use of the first polyphonic synthesizer, the Moog Apollo. It was released as a single, but failed to chart in the United Kingdom.[52][53]

An instrumental rendition of the hymn was included in the 1989 album "The Amsterdam EP" by Scottish rock band Simple Minds.[54]

Iron Maiden singer Bruce Dickinson incorporated the full text of the poem into his 6:42 track Jerusalem (co-written with Roy Z), a part of his William Blake inspired 1998 solo album The Chemical Wedding. Dickinson performed the track live in 2023 as part of the Jon Lord Concerto for Group and Orchestra tour.[55]

"Jerusalem" is traditionally sung before rugby league's Challenge Cup Final, along with "Abide with Me", and before the Super League Grand Final, where it is introduced as "the rugby league anthem". Before 2008, it was the anthem used by the national side, as "God Save the Queen" was used by the Great Britain team: since the Lions were superseded by England, "God Save the Queen" has replaced "Jerusalem". Since 2004, it has been the anthem of the England cricket team, being played before each day of their home test matches.

It was also used in the opening ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics held in London and inspired several of the opening show segments directed by Danny Boyle.[56] It was included in the ceremony's soundtrack album, Isles of Wonder.

Use in film, television and theatre

[edit]"Bring me my Chariot of fire" inspired the title of the film Chariots of Fire.[57] A church congregation sings "Jerusalem" at the close of the film and a performance appears on the Chariots of Fire soundtrack performed by the Ambrosian Singers overlaid partly by a composition by Vangelis. Unusually, "Jerusalem" is sung in four-part harmony, as if it were truly a hymn. This is not authentic: Parry's composition was a unison song (that is, all voices sing the tune – perhaps one of the things that make it so "singable" by massed crowds) and he never provided any harmonisation other than the accompaniment for organ (or orchestra). Neither does it appear in any standard hymn book in a guise other than Parry's own, so it may have been harmonised specially for the film. The film's working title was "Running" until Colin Welland saw a television programme, Songs of Praise, featuring the hymn and decided to change the title.[57][better source needed]

The hymn has featured in many other films and television programmes including Four Weddings and a Funeral, How to Get Ahead in Advertising, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, Saint Jack, Calendar Girls, Season 3: Episode 22 of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, Goodnight Mr. Tom, Women in Love, The Man Who Fell to Earth, Shameless, Jackboots on Whitehall, Quatermass and the Pit, Monty Python's Flying Circus, Spud 2: The Madness Continues, and Collateral (UK TV series). An extract was heard in the 2013 Doctor Who episode "The Crimson Horror" although that story was set in 1893, i.e., before Parry's arrangement. A bawdy version of the first verse is sung by Mr Partridge in the third episode of Series 1 of Hi-de-Hi!. A punk version is heard in Derek Jarman's 1977 film Jubilee. In an episode of Peep Show, Jez (Robert Webb) records a track titled "This Is Outrageous" which uses the first and a version of the second line in a verse.[58] A modified version of the hymn, replacing the word "England" with "Neo", is used in Neo Yokio as the national anthem of the eponymous city state.[59]

In the theatre it appears in Jerusalem,[44] Calendar Girls and in Time and the Conways.[44]

British band The Verve reworks lines from “Jerusalem” in their song “Love is Noise”, asking, "Will those feet in modern times/Walk on soles that are made in China?", and alludes to "bright prosaic malls". Another version of "Jerusalem" was produced by the British post-punk band The Fall in 1988.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The hymn 'Jerusalem the Golden with milk and honey blessed... I know not oh I know not what joys await me there....' uses Jerusalem for the same metaphor.

- ^ Blake wrote Englands here, and twice later, where standard English would normally use the spelling England's

- ^ Parry used those in his setting of the poem

- ^ Again, Blake wrote the genitive without an apostrophe

- ^ Incipit of citation given in Hall, 1996:

"And all the Arts of Life they changed into the Arts of Death in Albion.

The hour-glass contemned because its simple workmanship

Was like the workmanship of the Plowman and the water-wheel

That raises water into cisterns, broken and burned with fire

Because its workmanship was like the workmanship of the shepherd;

And in their stead intricate wheels invented, wheel without wheel

To perplex youth in their outgoings and to bind to labours in

Albion."

References

[edit]- ^ Cox, Michael, editor, The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature, "1808", p 289, Oxford University Press, 2004, ISBN 0-19-860634-6

- ^ Icons – a portrait of England. Icon: Jerusalem (hymn) Feature: And did those feet? Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 7 August 2008

- ^ Smith, A. W. (1989). "'And Did Those Feet...?': The 'Legend' of Christ's Visit to Britain". Folklore. 100 (1). Taylor and Francis: 63–83. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1989.9715752. JSTOR 1260001.

- ^ a b Whittaker, Jason (5 September 2022). "Anti-empire, anti-fascist, pro-suffragist: the stunning secret life of Proms staple Jerusalem". The Guardian.

- ^ "What's your anthem?". The One Show. BBC. 17 October 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Bring no spears to 'Jerusalem'". The Independent. 17 May 1996. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012.

- ^ "Great Poetry Explained". 25 February 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Rowland, Christopher (November 2007). "William Blake: a visionary for our time". OpenDemocracy. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ a b Blake, William. "Milton a Poem, copy B object 2". The William Blake Archive. Ed. Morris Eaves, Robert N. Essick, and Joseph Viscomi. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- ^ "Numbers 11:29". King James Version. biblegateway.com.

- ^ Lienhard, John H. 1999 Poets in the Industrial Revolution. The Engines of Our Ingenuity No. 1413: (Revised transcription)

- ^ Mosse, John (1967). "The Albion Mills 1784–1791". Transactions of the Newcomen Society. 40 (1): 47–60. doi:10.1179/tns.1967.004.

- ^ ICONS – a portrait of England. Icon: Jerusalem (hymn) Feature: And did those feet? Archived 12 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 7 August 2008

- ^ Brian Maidment, Reading Popular Prints, 1790–1870, Manchester University Press, 2001, p.40

- ^ Alfred Kazin: Introduction to a volume of Blake. 1946

- ^ Hall, Ernest (8 February 1996). "In Defense of Genius". Annual Lecture to the Arts Council of England. 21st Century Learning Initiative. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ Peter Porter, The English Poets: from Chaucer to Edward Thomas, Secker and Warburg, 1974, p.198., quoted in Shivashankar Mishra, The Rise of William Blake, Mittal Publications, 1995, p.184.

- ^ N. T. Wright, Bishop of Durham (23 June 2007) "Where Shall Wisdom be Found? Archived 22 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine" Homily at the 175th anniversary of the founding of the University of Durham. ntwrightpage.com

- ^ Quoted in Winters, Yvor (1967). Forms of Discovery. pp. 165–166.

- ^ Blake, William, Milton: A Poem, plate 4.

- ^ Gilroy, Amanda (2004). Green and Pleasant Land: English Culture and the Romantic Countryside. Peeters Publishers. p. 66.

- ^ "The history of the Earl of March public house". 24 September 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Crosby, Mark (3 October 2019). "Green and pleasant land". Goodwood.

- ^ "Eric Ravilious: Green and Pleasant Land," by Tom Lubbock, The Independent, 13 July 2010.. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ^ "This green and pleasant land," by Tim Adams, The Observer, 10 April 2005.. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ^ "Green and pleasant land?" by Jeremy Paxman, The Guardian, 6 March 2007.. Retrieved 7 January 2011

- ^ William Blake Archived 5 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Spartacus Educational (schoolnet.co) – Accessed 7 August 2008

- ^ Liukkonen, Petri. "William Blake". Books and Writers. Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- ^ Carroll, James (2011). Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-547-19561-2.

- ^ Bridges, Robert, ed. (January 1916). "Index". The Spirit of Man: An Anthology in English & French from the Philosophers & Poets (First ed.). Longmans, Green & Co. p. 335. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ Carroll, James (2011). Jerusalem, Jerusalem: How the Ancient City Ignited Our Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-547-19561-2.

- ^ C. L.Graves, Hubert Parry, Macmillan 1926, p. 92

- ^ "Link to PBS script quoting Attlee in 1945 – Accessed 7 August 2008". Pbs.org. 24 October 1929. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "What does it really mean to be English? Nothing at all – and that's how it should be". The Daily Telegraph. 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012.

- ^ Benoliel, Bernard, Parry Before Jerusalem, Ashgate, Aldershot, 1997

- ^ a b c Dibble, Jeremy, C. Hubert H. Parry: His life and music, Oxford University Press, 1992

- ^ Christopher Wiltshire (Former archivist, British Federation of Festivals for Music, Speech and Dance), Guardian newspaper 8 December 2000 Letters: Tune into Jerusalem's fighting history The Guardian 8 December 2000.

- ^ The manuscripts of the song with organ and with orchestra, and of Elgar's orchestration, are in the library of the Royal College of Music, London

- ^ ICONS – a portrait of England. Icon: Jerusalem (hymn) Sir Hubert Parry Archived 9 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine, "Jerusalem" and Elgar's orchestration.

- ^ On its being played at King George V opening the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, "British Table Talk", Christian Century (22 May 1924): 663; and Rubert Speaight, "England and St. George: A programme for St. George's Day [3 May], 1943", London Calling 169 (May 1943), iv.

- ^ Jerusalem: An Anthem for England. BBC Four. 8 July 2007.

- ^ Borland, Sophie (10 April 2008). "Cathedral bans popular hymn Jerusalem". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 April 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2008.

- ^ "Royal Wedding: Prince William and Kate Middleton choose popular hymns", The Telegraph, 29 April 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ a b c Brantley, Ben (20 July 2009). "Time, and the Green and Pleasant Land". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Parliamentary Early Day Motion 2791 Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, UK Parliament, 18 October 2006

- ^ "Correspondence". UK: Anthem 4 England. 8 May 2007. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ Sir Andrew Foster (30 May 2010). "England announce victory anthem for Delhi chosen by the public! – Commonwealth Games England". Weare England. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2011.

- ^ "Jerusalem: An Anthem for England (TV 2005)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ^ Sam Wollaston (9 September 2005). "Get me to the clink on time". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ "Jerusalem". SongFacts. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ The "Jam and Jerusalem" caricature of the WI is still current enough that they have a FAQ about it on their site at [1] Archived 11 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Brain Salad Surgery - Emerson, Lake & Palmer" – via www.allmusic.com.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (17 February 2014). "Keith Emerson talks ELP's Brain Salad Surgery track-by-track". MusicRadar. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ "Simple Minds - the Amsterdam EP". Discogs. 2 September 1989.

- ^ "Bruce Dickinson - Jerusalem (Zagreb 24.3.2023)". YouTube. 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Navigating the 'Isles of Wonder': A guide to the Olympic opening ceremony". CNN. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ^ a b IMDb trivia – Origin of title – Accessed 11 August 2008

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Toole, Mike (19 September 2017). "Neo Yokio Review". Anime News Network. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

Neo Yokio's national anthem is William Blake's 'Jerusalem,' and fight scenes are underpinned by tunes by the likes of Mingus.

External links

[edit]- Comparisons of the Hand Painted copies of the Preface on the William Blake Archive

- Free sheet music of Jerusalem from Cantorion.org

- And did those feet in ancient time at Hymnary.org

Jerusalem public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Multiple versions)

Jerusalem public domain audiobook at LibriVox (Multiple versions)

- 1804 poems

- 1916 songs

- English Christian hymns

- English patriotic songs

- National symbols of England

- Anthems of non-sovereign states

- Poetry by William Blake

- British Israelism

- Musical settings of poems by William Blake

- British anthems

- Joseph of Arimathea

- Hymns in The New English Hymnal

- Works based on the Book of Revelation

- 1800s neologisms

- 1800s quotations

- Quotations from literature

- Quotations from music