Tyre, Lebanon

Tyre

صور | |

|---|---|

City | |

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Latin | Ṣūr |

The Egyptian harbour with the submerged ancient columns with the skyline of the modern city in the background, aerial view of Tyre. | |

| Coordinates: 33°16′15″N 35°11′46″E / 33.27083°N 35.19611°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | South Governorate |

| District | Tyre |

| Municipalities | Abbassieh, Ain Baal, Borj Ech Chemali, Sour |

| Established | c. 2750 BCE |

| Area | |

• City | 4 km2 (2 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 17 km2 (7 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• City | 60,000 |

| • Density | 15,000/km2 (39,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 174,000 |

| Demonym | Tyrian |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 299 |

Tyre (/ˈtaɪər/; Arabic: صُور, romanized: Ṣūr; Phoenician: 𐤑𐤓, romanized: Ṣūr; Hebrew: צוֹר, romanized: Ṣōr; ‹See Tfd›Greek: Τύρος, translit. Týros) is a city in Lebanon, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world,[1] though in medieval times for some centuries by just a small population. It was one of the earliest Phoenician metropolises and the legendary birthplace of Europa, her brothers Cadmus and Phoenix, as well as Carthage's founder Dido (Elissa). The city has many ancient sites, including the Tyre Hippodrome, and was added as a whole to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1984.[2] The historian Ernest Renan noted that "One can call Tyre a city of ruins, built out of ruins".[3][4]

Today, Tyre is the fifth largest city in Lebanon after Beirut, Tripoli, Sidon, and Baalbek.[5] It is the capital of the Tyre District in the South Governorate. There were approximately 200,000 inhabitants in the Tyre urban area in 2016, including many refugees, as the city hosts three of the twelve Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon: Burj El Shimali, El Buss, and Rashidieh.[6]

Territory

[edit]Tyre juts out from the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, and is located about 80 km (50 mi) south of Beirut. It originally consisted of two distinct urban centres: Tyre itself, which was on an island just 500 to 700m offshore, and the associated settlement of Ushu on the adjacent mainland, later called Palaetyrus, meaning "Old Tyre" in Ancient Greek.[7] The fortified city was on top of a rock from which its name was inherited as "S‘r" is the Phoenician word for "rock". It had two ports, the "Sidonian port" to the north, still partly existing today, and the "Egyptian port" to the south which has perhaps been discovered very recently.[8]

Throughout history from prehistoric times onwards, all settlements in the Tyre area profited from the abundance of fresh water supplies, especially from the nearby springs of Rashidieh and Ras Al Ain in the South. In addition, there are the springs of Al Bagbog and Ain Ebreen in the North as well as the Litani River, also known as Alqasymieh.[9] The present city of Tyre covers a large part of the original island and has expanded onto and covers most of the causeway built by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE.[10] This isthmus increased greatly in width over the centuries because of extensive silt depositions on either side. The part of the original island not covered by the modern city of Tyre is mostly of an archaeological site showcasing remains of the city from ancient times.[citation needed]

Four municipalities contribute to Tyre city's 16.7 km2 built-up area, though none are included in their entirety: Sour municipality contains the heart of the city, excluding the Natural and Coastal Reserve; Burj El Shimali to the East without unpopulated agricultural lands; Abbasiyet Sour to the North without agricultural lands and a dislocated village; and Ain Baal to the South-East, also without agricultural lands and dislocated villages. Tyre's urban area lies on a fertile coastal plain, which explains the fact that as of 2017 about 44% of its territory was used for intra-urban agriculture, while built-up land constituted over 40%.[6]

In terms of geomorphology and seismicity, Tyre is close to the Roum Fault and the Yammouneh Fault. Though it has suffered a number of devastating earthquakes over the millennia, the threat level is considered to be low in most places and moderate in a few others. However, a tsunami following an earthquake and subsequent landslides and floods pose major natural risks to the Tyrian population.[6]

Vast reserves of natural gas are estimated to lie beneath Lebanese waters, much of it off Tyre's coast, but exploitation has been delayed by border disputes with Israel.[11]

Etymology

[edit]Early names of Tyre include Akkadian Ṣurru, Phoenician Ṣūr (𐤑𐤓), and Hebrew Ṣōr (צוֹר).[12] In Semitic languages, the name of the city means 'rock'[13] after the rocky formation on which the town was originally built.

The predominant form in Classical Greek was Týros (Τύρος), which was first seen in the works of Herodotus but may have been adopted considerably earlier.[12] It gave rise to Latin Tyrus, which entered English during the Middle English period as Tyre.[14] The demonym for Tyre is Tyrian, and the inhabitants are Tyrians.[citation needed]

Climate

[edit]

Tyre has a Hot-summer mediterranean climate (classified as Csa under the Köppen climate classification), characterized by six months of drought from May to October. On average, it has 300 days of sun a year and a yearly temperature of 20.8°C. The average maximum temperature reaches its highest at 30.8 °C in August and the average minimum temperature its lowest at 10 °C in January. On average, the mean annual precipitation reaches up to 645 mm. The temperature of the sea water reaches a minimum of 17 °C in February and a maximum of 32 °C in August. At a depth of 70 m it is constantly at 17–18 °C.[15]

Meanwhile, rising sea levels due to global warming threaten coastal erosion to Tyre's peninsula and bay areas.[16]

History

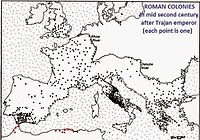

[edit]The ancient city of Tyre is located along the coast of Phoenicia in modern Lebanon. The site has been occupied since the Bronze Age.[17] The city became a prominent Phoenician city-state between the 9th and 6th centuries BCE, settling prestigious colonies around the Mediterranean Sea, such as Carthage and Leptis Magna.[18] It went under Persian rule in 572 BCE, before being conquered by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE. Monumental archaeological remains dated from the subsequent Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Medieval periods led to its inscription on its archaeological remains on the UNESCO World’s Heritage list in 1984.

The Roman historian Justin wrote that the original founders arrived from the nearby city of Sidon in the quest to establish a new harbour. The famous Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484–425 BCE), born in the city of Halicarnassus, visited Tyre around 450 BCE at the end of the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BCE), and wrote in his Histories that according to the priests there, the city was founded 2300 years earlier (around 2750 BCE),[19] as a walled place upon the mainland, now known as Paleotyre (Old Tyre).

The Phoenician Tyrians' international trade network was based on its two harbours which are mentioned by ancient writers (Arrian, Anabasis, 2, 24; Strabo, Geography, 16,2,23).[20][21] The northern harbour opened toward the Phoenician city of Sidon and has been therefore referred to as the “Sidonian Harbour” by 19th and 20th century scholars, but it was referred to as the "Port of Astronoe" during Late Antiquity.[22] The southern harbour opened toward Egypt and was referred to as the “Egyptian Harbour”. The location of the two harbours has been the subject of speculations since the 17th Century.[23] The submarine excavation of a large, 4-6th Century BCE breakwater north of the city,[24][25] and the discovery of 250 BCE to 500 CE harbour sediments behind this breakwater[26] demonstrated the existence of a northern harbour repeatedly, if not permanently, throughout Antiquity under the modern harbour of Tyre.

The location of the southern harbour is more elusive. Renan (1864–1874) envisioned it as an extensive structure now located offshore, south of the former island. Subsequent diving surveys identified submerged man-made structures on the seafloor within 150 m of the former island.[27][28] Antoine Poidebard, who was the first to have them explored by divers in 1939, saw in these structures former breakwaters enclosing a harbour with two entrances.[29] The geographic area enclosed within these structures is therefore often referred to as the “Southern Harbour”. These structures have also been interpreted as a polder-like area protecting an urban district (El-Amouri et al., 2005; Frost, 1971; Renan, 1864–1874). A Phoenician-style breakwater was recently found within this area, but excavation is needed to confirm its age ascription.[30] Harbour sediments found behind the structure suggest that the breakwater was part of the Egyptian harbour.[31][32] Harbour sediments found near Hiram's Tower, further north, mark an early location of the Sidonian Harbour.[31]

The development of Tyre was profoundly affected by the construction of a causeway built by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE to seize the city.[10] This reportedly 750 m-long[33] and 60 m-wide causeway was laid over a submarine shoal less than 5.4 m deep.[34] This shoal was interpreted as a sandbank (also called a ‘salient’), formed by the accretion of sand in the lee of the island, under the effects of the refraction and diffraction of waves around the island. The causeway interrupted longshore sand transport, forcing sand to accumulate along the causeway, rapidly creating an emerged sandy isthmus (or tombolo), linking the island to the mainland.[35][36]

This sandy isthmus rapidly inflated during the centuries following the construction of the causeway. By early Imperial Roman times, monumental buildings had been built over most of its surface. Their layout implies that the isthmus was by then nearly as wide as today. Therefore, the isthmus had completely reshaped the eastern coast of Tyre Island within 6–10 centuries after the construction of the causeway, spurring a radical transformation of the city.[citation needed]

Coast Nature Reserve

[edit]Tyre enjoys a reputation of having some of the cleanest beaches and waters of Lebanon.[37][38] However, a UN HABITAT profile found that "seawater is also polluted due to wastewater discharge especially in the port area".[6] There is still also considerable pollution by solid waste.[39]

The Tyre Coast Nature Reserve (TCNR) was decreed in 1998 by the Ministry of Public Works. It is 3.5 km (2.2 mi) long and covers over 380 hectares (940 acres). The TCNR is within the best preserved stretch of sandy coastline in southern Lebanon and divided into two section zones: a 1.8 km sand lined beach, 1.8 km long and 500 meters wide-ranging from the Tyre Rest House in the north to the Rashidieh Refugee Camp in the South, and a stretch of 2 km with agriculture lands of small family farms and the springs of Ras El Ain with three constantly flowing artesian wells, ranging from Rashidieh to the village of Chaetiyeh in the South.[15]

The former is divided into two zones: one for tourism that features a public beach of some 900 m and restaurant tents during the summer season hosting up to 20,000 visitors on a busy day, and another 900 m of conservation zone as a sanctuary for sea turtles and migrating birds.[39]

Due to its diverse flora and fauna, the reserve was designated a Ramsar Site in 1999 according to the international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of Wetlands, since it is considered "the last bio-geographic ecosystem in Lebanon". It is an important nesting site for migratory birds, the endangered Loggerhead and green sea turtle, the Arabian spiny mouse and many other creatures (including wall lizards, common pipistrelle, and European badger).[40][41] Also, there are frequent sighting of dolphins in the waters off Tyre.[42] Altogether, the TCNR includes:

275 species distributed over 50 families. In addition, the reserve is home to seven regionally and nationally threatened species, 4 endemic and 10 rare species, whilst 59 species are restricted to the Eastern Mediterranean area. It is also worthy to indicate that, several bio-indicator species as well as 25 medicinal species were recognized. TCNR encloses flora species belonging to the various habitats: the sandy shore, rocky shore, littoral and Freshwater ecosystems. A wide number of Gramineae, Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Umbellifereae families dominate the floristic resources.[15]

However, the biodiversity of the TCNR is threatened as shown by a strong decrease in the numbers of the caspian terrapin Mauremys caspica, the green toad Bufo viridis and the tree frog Hyla savigny. Also, since the 2000s, the North American camphorweed Heterotheca subaxillaris has invaded the TCNR as a neophyte from Haifa across the Blue Line.[15]

During the 2006 war, turtle breeding areas were affected when the IDF bombed the conservation site.[43]

The oil spill which devastated the coast north of Ashkelon in February 2021 also contaminated Tyre's beaches.[44]

Historical and cultural heritage

[edit]

Arguably the most lasting Phoenician legacy for the Tyrian population has been the linguistic mark that the Syriac and Akkadian languages have left on the Arabic spoken in the region of Tyre.[45][full citation needed] Most notably, the widely used term "Ba'ali" – which is used especially to describe vegetables and fruits from rain-fed, untreated agricultural production – originates from the Baal religion.[46] The Tyrian municipality of Ain Baal is apparently also named after the Phoenician deity.[47] The most visible part of ancient and medieval history on the other side have been the archaeological sites though:

The first archaeological excavations were by Ernest Renan in 1860 and 1861.[48] He was followed in the 1870s by Johannes Nepemuk Sepp. His most notable work was excavating at the cathedral in an attempt to find the bones of Frederick Barbarossa.[49] More work was undertaken in 1903 by the Greek archaeologist Theodore Makridi, curator of the Imperial Museum at Constantinople. Important findings like fragments of marble sarcophagi were sent to the Ottoman capital.[50][51]

In 1921, an archaeological survey of Tyre was done by a French team under the leadership of Denyse Le Lasseur in 1921.[52] It was followed by another mission between 1934 and 1936 that included aerial surveys and diving expeditions. It was led by the Jesuit missionary Antoine Poidebard, a pioneer of aerial archaeology.[53]

Large-scale excavations started in 1946 under the leadership of Emir Maurice Chéhab (1904–1994), "the father of modern Lebanese archaeology" who for decades headed the Antiquities Service in Lebanon and was the curator of the National Museum of Beirut. His teams uncovered most remains in the Al Bass/Hippodrome and the City Site/Roman baths.[54][55][56]

During the 1960s, Honor Frost (1917–2010) – the Cyprus-born pioneer of underwater archaeology initiated several investigations "aimed at identifying and documenting the significant archaeological potential for harbour facilities within coastal Tyre". Based on the results, she suggested that the Al Mobarakee Tower may actually date back to Hellenistic times.[57]

All those works stopped though soon after the 1975 beginning of the Civil War and many records were lost.[54]

In 1984, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) declared Tyre a World Heritage Site in an attempt to halt the damage being done to the archaeological sites by the armed conflict and by anarchic urban development.[37]

In the late 1980s, "clandestine excavations" took place in the Al-Bass cemetery, which "flooded the antiquities market".[58]

Regular excavation activities only started again in 1995 under the supervision of Ali Khalil Badawi.[59] Shortly afterwards, an Israeli bomb destroyed an apartment block in the city and evidence for an early church was revealed underneath the rubble. Its unusual design suggests that this was the site of the Cathedral of Paulinus which had been inaugurated in 315 CE.[60]

In 1997, the first Phoenician cremation cemetery was uncovered in the al-Bass site, near the Roman necropolis.[61] Meanwhile, Honor Frost mentored local Lebanese archaeologists to conduct further underwater investigations, which in 2001 confirmed the existence of a human-made structure within the northern harbour area of Tyre.[57]

In 2003, Randa Berri, president of the National Association for the Preservation of South Lebanon's Archaeology and Heritage and wife of Nabih Berri, veteran leader of the Amal Movement and longtime Speaker of the Parliament of Lebanon, patronized a plan to renovate Khan Sour / Khan Al Askaar, the former Ma'ani palace, and convert it into a museum.[62] As of 2019, nothing was done in that regard and the ruins have kept on crumbling.

The hostilities of the 2006 Lebanon War put the ancient structures of Tyre at risk. This prompted UNESCO's Director-General to launch a "Heritage Alert" for the site.[63] Following the cessation of hostilities in September 2006, a visit by conservation experts to Lebanon observed no direct damage to the ancient city of Tyre. However, the bombardment had damaged frescoes in a Roman funerary cave at the Tyre Necropolis. Additional site degradation was also noted, including "the lack of maintenance, the decay of exposed structures due to lack of rainwater regulation and the decay of porous and soft stones".[64]

Since 2008, a Lebanese French team under the direction by Pierre-Louis Gatier of the University of Lyon has been conducting archaeological and topographical work. When international archeological missions in Syria came to a halt after 2012 due to the war there, some of them instead started excavations in Tyre, amongst them a team headed by Leila Badre, director of the Archeological Museum of the American University of Beirut (AUB), and Belgian archaeologists.[54]

Threats to Tyre's ancient cultural heritage include development pressures and the illegal antiquities trade.[65] A highway, planned for 2011, was expected to be built in areas that are deemed archaeologically sensitive.[66] A small-scale geophysical survey indicated the presence of archaeological remains at proposed construction sites. The sites have not been investigated. Despite the relocation of a proposed traffic interchange, the lack of precise site boundaries confuses the issue of site preservation.[64]

A 2018 study of Mediterranean world heritage sites found that Tyre's City site has "the highest risk of coastal erosion under current climatic conditions, in addition to 'moderate' risk from extreme sea levels."[67] Further coastal inspection was conducted in 2019, leading to a new hypothesis about the local relative sea level rise and to discovery of yet unreported submerged coastal structures.[68]

Like many of the cities in the Levant and in Lebanon, the architecture since the Lebanese Civil War in the 1970s has been of poor quality, which tend to threaten the cultural heritage in the built environment before the war.[69][70] Meanwhile, historical buildings from the Ottoman period like Khan Rabu and Khan Sour / Khan Ashkar have partly collapsed after decades of total neglect and lack of any maintenance whatsoever.[70]

In 2013, the International Association to Save Tyre (IAST) made headlines when it launched an online raffle in association with Sotheby's to fund the artisans' village Les Ateliers de Tyr at the outskirts of the city. Participants could purchase tickets for 100 euros to win the 1914 Man in the Opera Hat painting by Pablo Picasso.[71] The proceeds totaled US$5.26 million. The painting was won by a 25-year-old fire-safety official from Pennsylvania.[72] IAST president Maha al-Khalil Chalabi is a daughter of feudal lord and politician Kazem el-Khalil.[73] In September 2017, she opened "Les Atelier", which is located in the middle of an orange grove covering an area of 7.300 m2 at the northeastern outskirts of Tyre.[74]

Biblical description

[edit]

The city of Tyre appears in many biblical traditions:

Hebrew Bible / Old Testament

[edit]- According to Joshua 19, "the fortified city of Tyre" was allotted to the Tribe of Asher.[75]

- King Hiram I of Tyre allied himself with David and Solomon in 2 Samuel, 1 Kings and 1 Chronicles.[76] Hiram provided architects, workmen, cedar wood, and gold to build the royal palace in Jerusalem, as well as the Temple.[77]

- Tyre is listed among an alliance of ten nations that would conspire against God's people.[78]

- Tyre is mentioned in the Book of Isaiah as being forgotten for 70 years when her "fortress is destroyed" and after which "her profit and her prostitute's wages will be sacred to the Lord."[79]

- The Book of Joel groups Tyre, Sidon and Philistia together and it states that the people of Judah and Jerusalem were sold to the Greeks, and there would thus be punishment because of it.[80]

- Tyre is also mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel,[81] Book of Amos,[82] the Psalms, and the Book of Zechariah[83] which prophesied its destruction.

New Testament

[edit]- Jesus visited the region or "coasts" (King James Version) of Tyre and Sidon[84] and from this region many came forth to hear him preaching,[85] leading to the stark contrast in Matthew 11:21[86] to his reception in Korazin and Bethsaida.

- Herod was said to be angry with the people of Tyre and Sidon and he delivered a public address upon which he was struck down by God after not giving glory to him once he received praise arrogantly according to the Book of Acts.[87] The same book describes Paul's voyage to Tyre where he stayed for seven days.[88]

- In the Book of Revelation,[89] chapter 18 alludes extensively to the mercantile description of Tyre in Ezekiel 26–28.

Other writings

[edit]- Apollonius of Tyre is the subject of an ancient short novella, popular in the Middle Ages. Existing in numerous forms in many languages, the text is thought to be translated from an ancient Greek manuscript, now lost.

- Pericles, Prince of Tyre is a Jacobean play written at least in part by William Shakespeare and George Wilkins. It is included in modern editions of his collected works despite questions over its authorship.

- In 19th-century Britain, Tyre was several times taken as an exemplar of the mortality of great power and status, for example by John Ruskin in the opening lines of The Stones of Venice and by Rudyard Kipling's Recessional.

- Tyrus is the title and subject of a poem by the Cumbrian poet Norman Nicholson in his collection 'Rock Face' of 1948.

- The French comic book artist Albert Uderzo published in 1981 Asterix and the Black Gold which describes Asterix's and Obelix's voyage to the Middle East featuring James Bond and biblical themes: in their quest for petroleum, they sail on board a Phoenician ship, but the Roman regime closes off the ports of Tyre in order to deny their landing.

- In 2015, the French Lebanese artist Joseph Safieddine published the graphic novel drama Yallah Bye which offers an account of his family's fate during the 2006 war between Israel and Hezbollah, when they sought refuge in the Christian quarter of Tyre. An English version followed in 2017 and an Arabic one in 2019.

Astronomical objects

[edit]A multi-ring structured region on Europa, the smallest of the four Galilean moons orbiting Jupiter, is named after Tyre, the legendary birthplace of princess Europa. Originally called "Tyre Macula", it is some 140 kilometers in diameter (about the size of the island of Hawaii) and thought to be the site where an asteroid or comet impacted Europa's ice crust.[90]

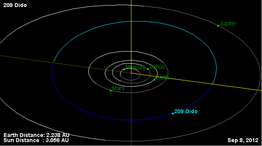

The asteroid 209 Dido is named after the legendary Tyrian-Carthaginian princess. It is a very large main-belt asteroid, classified as a C-type asteroid which is probably composed of carbonaceous materials. 209 Dido was discovered in 1879 by C. H. F. Peters.

Cultural life

[edit]The first cinema in Tyre opened in the late 1930s when a café owner established makeshift film screenings.[91] Hamid Istanbouli – a fisherman by profession, who was also a traditional storyteller (hakawati) and thus interested in cinema – projected films on the wall of a Turkish hammam.[92] In 1939 the Roxy opened, followed in 1942 by the "Empire":[93]

By the mid-1950s there were four cinemas in Tyre, and four more soon opened in nearby Nabatieh. Many also hosted live performances by famous actors and musicians, serving as community spaces where people from different backgrounds came together.[91]

In 1959, the "Cinema Rivoli of Tyre" opened and quickly became one of the prime movie theatres of the country. According to UNIFIL, it was visited "by celebrity who's whos of the time, including Jean Marais, Brigitte Bardot, Rushdi Abaza and Omar Hariri."[94] In 1964, the "Dunia" opened,[95] two years later followed by the "Al Hamra Cinema",[93] which became a venue for some of the Arab world's most famous performers, like Mahmoud Darwish, Sheikh Imam, Ahmed Fouad Negm, Wadih el-Safi, and Marcel Khalife.[91]

Meanwhile, two Tyrian artists had a major impact on the development of Lebanese music: Halim el-Roumi (1919–1983) and Ghazi Kahwaji (1945–2017). Some sources claim that the famous musician, composer, singer and actor el-Roumi was born in Tyre to Lebanese parents. However, others suggest that he was born in Nazareth and moved to Tyre from Palestine.[96] For some time, he worked as a teacher at the Jafariya High School there. In 1950 he became director of Radio Lebanon's music department,[97] where he discovered the singer Fairuz and introduced her to the Rahbani brothers.[98] Roumi composed music for and with them in close collaborations.[99]

Kahwaji was Lebanon's first scenographer and for three decades the artistic general director for the Rahbani brothers and Fairuz. He used this prominent position to promote "against confessionalism and fundamentalism".[100] Kahwaji, who was also a professor at the Lebanese University (LU) and the Saint Joseph University in Beirut,[101] published between 2008 and 2010 the sarcastic three-volume book series "Kahwajiyat" about social injustice in the Arab world.[100]

By then, cultural life in Tyre had been severely affected by armed conflict as well. In 1975, the commercial "Festivals de Tyr" – organised by Maha al-Khalil Chalabi, the daughter of feudal landlord and politician Kazem al-Khalil – were supposed to debut but stopped at the outbreak of the Civil War.[102]

Some cinemas were damaged by Israeli bombardment in 1982 and all of them eventually closed down, the last ones in 1989:[91] the Hamra and the AK2000.[93]

In the mid-nineties though, first the idea of a commercial Tyre International Festival was revived. It has been organised since then annually in the ancient site of the Roman hippodrome, featuring international artists like Elton John and Sarah Brightman,[103] as well as Lebanese stars Wadih El Safi, Demis Roussos, Kadim Al-Saher, Melhem Barakat, Julia Boutros, and Majida El Roumi,[46] the daughter of Halim el-Roumi.

In 2006, the "Centre de Lecture et d’Animation Culturelle" (C.L.A.C.) was opened by Tyre's municipality as the first public library of the city, with support from the Lebanese Ministry of Culture and the French Embassy in Beirut. It is located in the historical building of the "Beit Daoud" next to the "Beit El Medina", the former Mamluk House, in the old town.[104]

In 2014, the NGO Tiro Association for Arts rehabilitated the defunct cinema Al Hamra under the leadership of "Palestinian-Lebanese street theater performer, actor, comedian, and theater director"[105] Kassem Istanbouli (*1986). His grandfather was one of the founders of cinema in Tyre and his father used to repair cinema projectors.[92]

In 2018, the Istanbouli Theatre troupe rehabilitated and moved to the Rivoli Cinema,[106] which had been closed since 1988,[107] to establish the non-commercial Lebanese National Theater as a free cultural space with free entrance and a special focus on training children and youth in arts. It also runs the "Mobile Peace Bus", which is decorated with graffiti of Lebanese cultural icons, to promote arts in the villages of the neighbouring countryside.[108] Istanbouli has argued:

In Tyre, we have 400 shops for shisha, one library, and one theatre. But if there are places, people will come.[109]

In 2019, the film Manara (Arabic for "lighthouse") by Lebanese director Zayn Alexander, who shot the movie at the Al Fanar resort in Tyre, won the Laguna Sud Award for Best Short Film at the Venice Days Strand festival.[110]

-

The ruins of the building that used to house the Empire cinema, 2019

-

Halim El Roumi

-

Layal Abboud in 2015

-

Karim Istanbouli in 2019 at the Rivoli

-

Video of the carnival during the TIRO INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL 2019

Education

[edit]

There are many universities in Lebanon.

The Jafariya School was founded in 1938 by Imam Abdul Hussein Sharafeddin.[111] It soon expanded thanks mainly to donations from rich émigrés and thus was upgraded in 1946 to be a Secondary School, the first in Southern Lebanon (see above). It has remained one of the main schools in Tyre ever since.[112]

An important role in the Tyrian education landscape is played by the charity organisation of the vanished Imam Musa al-Sadr, which has been headed since his disappearance in 1978 by his sister Rabab al-Sadr.[113] While the foundation operates in various parts of the country, its main base is a compound on the southern entry of the Tyre peninsula close to the sea. A major focus is its Orphanages, but it also runs adult educational and vocational training programmes, especially for young women, in addition to health and development projects.[114]

Musa Sadr also laid the groundwork for establishing the Islamic University of Lebanon (IUL) which was finally licensed in 1996 and opened a branch on the seafront,in Tyre. Its board of trustees is dominated by representatives of the Supreme Shiite Council, founded by Sadr in 1967.[115]

The Lebanese Evangelical School in Tyre with a history of more than 150 years is arguably the largest school in town. Collège Élite, a French international school opened in 1996, is another one of a host of private schools in Tyre. The Cadmous College - a pre-kindergarten to grade 12 school, run by the Maronite missionaries - has about 10% Christian and 90% Muslim pupils.[116]

In August 2019, the 17-year-old Ismail Ajjawi – a Palestinian resident of Tyre and graduate of the UNRWA 'Deir Yassin' High School in the El-Buss refugee camp[117] – made global headlines when he scored top-results to earn a scholarship to study at Harvard, but was deported upon arrival in Boston despite valid visa.[118] He was readmitted ten days later to start his studies in time.[119]

Demographics

[edit]In 2014 Muslims made up 78,64% and Christians made up 21,02% of registered voters in Tyre. 66,29% of the voters were Shiite Muslims, 12,33% were Sunni Muslims and 12,03% were Greek Catholics.[121]

An accurate statistical accounting is not possible, since the government of Lebanon has released only rough estimates of population numbers since 1932.[122]

The Lebanese nationality population of Tyre is predominantly Shia Muslim with a small but noticeable Christian community. In 2010, it was estimated that Christians accounted for 15% of Tyre's population.[123] In 2017, the Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre counted about 42,500 members. Most of them live in the mountains of Southern Lebanon, while there are just some 500 Maronites in Tyre itself. The Melkite Greek Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre – which not only covers the District of Tyre in the South Governorate but also neighbouring areas in the Nabatieh Governorate – registered 2,857 members in that year.[124]

Refugees

[edit]The city of Tyre has become home to more than 60,000 Palestinian refugees who are mainly Sunni Muslims with some Christian families. Tyre hosted Shias from the seven villages that were depopulated in 1948, they settled in suburbs like Shabriha. As of June 2018, there were 12,281 registered persons in the Al Buss camp,[125] 24,929 in Burj El Shimali[126] and 34,584 in Rashidieh.[127] In the ramshackle "gathering" of Jal Al Bahar next to the coastal highway, the number of residents was estimated to be around 2,500 in 2015.[128]

In all camps, the number of refugees from Syria and Palestinian refugees from Syria increased in recent years.[127] Tensions developed since these new arrivals would often accept work in the citrus and banana groves "for half the daily wage" that local Palestinian refugees used to earn.[129]

In early 2019, some 1,500 Syrian refugees were evicted from their informal settlements around the Litani river for allegedly polluting the waters which are already heavily contaminated.[130]

Foreign workers

[edit]

Tyre is known as "Little West Africa". Many families in Tyre have relatives in the Western Africa diaspora, especially in Senegal, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast and Nigeria. In Senegal, most immigrants originated from Tyre. Member of the Tyrian communities there are "primarily second, third and fourt generation migrants, many of whom have never been to Lebanon." One of Tyre's main promenades is called "Avenue du Senegal".[112]

As there were an estimated 250,000 foreign workers – mostly Ethiopian women – under the discriminatory Kafala system of sponsorship in Lebanon by 2019,[131] there is also a large community of African migrants in Tyre. They are mainly Ethiopian women who work as domestic servants. Some of them celebrate church service at the Greek-Catholic Cathedral of Saint Thomas, which has devoted a chapel on its compound to Tyre-born Saint Frumentius, the first bishop of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. In April 2014 one Ethiopian made headlines in an apparent suicide in Tyre:

Media reports said the woman had fled last week from her employer's home. Security forces later detained the Ethiopian and returned her to her employer[132]

Poverty

[edit]The 2016 UN HABITAT profile found that:

Approximate calculations suggest that 43% of Lebanese in Tyre urban area are living in poverty.[6]

Economy

[edit]

The economy of urban Tyre mostly depends on tourism, contracting services, the construction sector, and remittances from Tyrians in the diaspora, especially in West Africa.[6]

UNIFIL contributes greatly to the purchasing power in the Tyrian economy as well, both through spending by its individual members as well as through "quick-impact projects" like gravelling road, rehabilitating public places etc.[11]

As of 2016, Olive trees were reported to comprise 38% of Tyre's agricultural land, but producers lacked a collective marketing strategy. While Citrus reportedly comprised 25% of the agricultural land, 20% of its harvest ended up wasted.[133]

Tyre houses one of the nation's major ports, though much smaller than the ports of Beirut, Tripoli, and also Sidon/Saida. Its cargo traffic has been limited to the periodical import of used cars. One day after the 2020 Beirut explosion which devastated the Port of Beirut and much of the national capital on 4 August the national government reportedly decided to use the Port of Tyre as a back-up for the Port of Tripoli.[134]

In the harbour area, the Barbour family of shipbuilders continues to build wooden boats.[135] Tyre is thus one of only a few cities in the Mediterranean that has kept this ancient tradition, although the Barbour business has been struggling to survive as well. By 2004, there were "over 600 fishermen [..] striving to make ends meet in Tyre alone".[136]

Lebanon's General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (GDLRC) recorded for Tyre a 4.4 percent growth rate for land transactions between 2014 and 2018, the highest rate in the country during that period.[137] This increase in real estate prices has been largely attributed to the inflow of remittances from diaspora Tyrians.[6]

Off the Tyrian coast, block 9 has been awarded for deepwater drilling of natural gas to a consortium of French company TotalEnergies, Italy-based Eni, and Russian Novatek.[138]

Sports

[edit]

Tadamon Sour Sporting Club, or simply Tadamon (meaning "Solidarity"), nicknamed "The Ambassador of the South", was founded in 1946 and is thus the historically most established football club of Tyre. They play their home matches at the Tyre Municipal Stadium and have won one Lebanese FA Cup (2000–01) and two Lebanese Challenge Cups (2013 and 2018). Tadamon's traditional rivals, Salam Sour Sports Club, are also based in Tyre.[citation needed]

According to BBC reports, Tadamon SC was stripped of its Lebanese Premier League championship title in 2001 following match-fixing allegations.[139]

In the same year the club scored arguably one of its biggest transfers when Roda Antar from its own youth teams was loaned to Germany's Hamburger SV for two seasons. After eight years in Germany with Hamburg, SC Freiburg and 1. FC Köln he played another six years in the Chinese Super League and then returned to Tadamon for one final season before retirement.[citation needed]

A number of Lebanese Premier League professional footballers, who have also played for the Lebanon national team, originate from Tyre, namely Rabih Ataya,[140] and Nassar Nassar.[141]

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Tyre is twinned with:

Notable people

[edit]

- Hiram I, Biblical King of Tyre

- Pygmalion of Tyre, King of Tyre

- Belus, King of Tyre in the Aeneid

- Dido, founder-heroine of Carthage

- Diodorus of Tyre (late 2nd century BCE), Peripatetic philosopher and scholarch (head) of the Peripatetic school of Athens

- Antipater of Tyre (1st century BCE), Stoic philosopher

- Adrianus, a sophist

- Apollonius of Tyre (philosopher) (c. 50 BCE), philosopher

- Marinus of Tyre, Hellenic geographer, cartographer and mathematician whose works greatly influenced Ptolemy's famous Geography as acknowledged by Ptolemy

- Ulpian (early 3rd century CE), Famous Roman jurist who taught at the renowned Law school at Beirut

- Meropius of Tyre (Μερόπιος), a philosopher, traveled together with two of his relatives, Frumentius (Φρουμέντιος) and Edesius (Εδέσιος) to ancient India.[143][144]

- Saint Christina of Tyre (3rd century CE) Martyr[145]

- Porphyry, Neoplatonic philosopher and writer, he edited and published The Enneads of Plotinus and his Isagoge, an introduction to logic and philosophy, was the standard textbook on logic throughout the Middle Ages

- Allaqa (10th century), mariner who led revolt against Fatimid Caliphate[146]

- William of Tyre, (12th century CE), historian and Archbishop of Tyre

- Abdel Hussein Sharafeddine, Shi'a reformer

- Musa Sadr, Shi'a leader

- Rabab al-Sadr, Activist, sister of former

- Halim el-Roumi, singer and composer

- Nabih Berri, leader of the Amal movement

- As'ad AbuKhalil, anarchist and professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus

- Zaki Chehab, founder and editor-in-chief of ArabsToday.net

- Alaa Zalzali, singer

- Joe Barza, chef and television personality

- Périhane Chalabi Cochin, TV host

- Rabih Ataya (born 1989), Lebanese football player[140]

- Nassar Nassar (born 1992), Lebanese football player[141]

- Bilal Najdi (born 1993), Lebanese football player[147]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The world's 20 oldest cities". The Telegraph. 30 May 2017. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "World Heritage List: Tyre". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ Medlej, Youmna Jazzar; Medlej, Joumana (2010). Tyre and its history. Beirut: Anis Commercial Printing Press s.a.l. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-9953-0-1849-2.

- ^ Finlay, Victoria (2014). Colour: Travels Through the Paintbox. London: Hachette UK. ISBN 9780340733295.

- ^ "Tyre (Sour) City, Lebanon". tyros.leb.net.

- ^ a b c d e f g Maguire, Suzanne; Majzoub, Maya (2016). Osseiran, Tarek (ed.). "TYRE CITY PROFILE" (PDF). reliefweb. UN HABITAT Lebanon. pp. 12, 16, 33–34, 39–43, 57, 72. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Presutta, David. The Biblical Cosmos Versus Modern Cosmology. 2007, page 225, referencing: Katzenstein, H.J., The History of Tyre, 1973, p.9

- ^ Goiran, J-P, et al., 2023, "Evolution of Sea Level at Tyre During Antiquity", BAAL 21, with a new hypothesis about the local relative sea level rise and a major discovery of the Phoenician breakwater of the southern, so-called "Egyptian", harbour [1]

- ^ Badawi, Ali Khalil (2018). TYRE (4th ed.). Beirut: Al-Athar Magazine. pp. 5, 7.

- ^ a b Heather Whipps (14 May 2007). "Mystery Solved: How Alexander the Great Defeated Tyre". livescience.com. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Ten ways to develop southern Lebanon". The New Humanitarian. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ a b Woodhouse, Robert (2004). "The Greek Prototypes of the City Names Sidon and Tyre: Evidence for Phonemically Distinct Initials in Proto-Semitic or for the History of Hebrew Vocalism?". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 124 (2): 237–248. doi:10.2307/4132213. JSTOR 4132213.

- ^ Bikai, P., "The Land of Tyre", in Joukowsky, M., The Heritage of Tyre, 1992, chapter 2, p. 13

- ^ "Tyre". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Yacoub, Adel; El Kayem, Cynthia; Moukaddem, Tala (15 September 2011). "Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)–2009-2012version" (PDF). Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Brown, Sally (16 October 2018). "University research shows world heritage sites under threat from climate change". University of Southampton. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "A History of the Ancient & Classical City of Tyre and Its Commerce". TheCollector. 17 October 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Tyre | Ancient City & Historical Site | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 23 April 2024. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, Book 2. Greek original

- ^ "Arrian, Anabasis, book 2, chapter 24, section 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ "Strabo, Geography, BOOK XVI., CHAPTER II., section 23". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Aliquot, Julien (2020). "The Port of Astronoe in Tyre". Bulletin d'Archéologie et d'Architecture Libanaises. Hors- Série 18: 61–70 – via HAL.

- ^ Renan, E., 1864-1874. Mission de Phénicie dirigée par Ernest Renan: Texte. Impr. impériale.

- ^ Castellvi, G., Descamps, C., Kuteni, V.P., 2007. Recherches archéologiques sous-marines à Tyr.

- ^ Noureddine, I., Mior, A., 2013. Archaeological Survey of the Phoenician Harbour at Tyre, Lebanon.

- ^ Marriner, N., Morhange, C., Doumet-Serhal, C., Carbonel, P., 2006. Geoscience rediscovers Phoenicia's buried harbors. Geology 34, 1-4.

- ^ El-Amouri, M., El-Hélou, M., Marquet, M., Noureddine, I., Seco Alvarez, M., 2005. Mission d'expertise archéologique du port sud de Tyr, résultats préliminaires. Baal Hors Série II, 91-110.

- ^ Frost, H., 1971. Recent observations on the submerged harbourworks at Tyre. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth 24, 103-111.

- ^ Poidebard, A., 1939. Un grand port disparu: Tyr: recherches aériennes et sous-marines: 1934-1936. P. Geuthner.

- ^ Goiran, Jean-Philippe; Brocard, Gilles; De Graauw, Arthur; Kahwagi-Janho, Hany; Chapkanski, Stoil (2021). "Evolution of sea level at Tyre during Antiquity". Bulletin d'Archéologie et d'Architecture Libanaise. 21: 305–316.

- ^ a b Brocard, Gilles; Goiran, Jean-Philippe; de Graauw, Arthur; Chapkanski, Stoil; Dapoigny, Arnaud; Régagnon, Emmanuelle; Husson, Xavier; Bolo, Aurélien; Pavlopoulos, Kosmas; Fouache, Eric; Badawi, Ali; Yon, Jean-Baptiste (15 January 2024). "Growth of the sandy isthmus of tyre and ensuing relocation of its harbors". Quaternary Science Reviews. 324: 108463. Bibcode:2024QSRv..32408463B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108463. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 266282297.

- ^ Arthur de Graauw, Gilles Brocard et Jean-Philippe Goiran. (26 January 2024). "Where is the Phoenician harbour of Tyre?". doi:10.58079/vom2.

- ^ four stades acc. to Diodorus Siculus, Hist, 17, 7 and to Quintus Curtius Rufus, Hist, 4, 2, but 700 paces acc. to Pliny, Natural History V, 17

- ^ three fathoms acc. to Arrian, Anabasis, 2, 18

- ^ Marriner, N., Goiran, J., Morhange, C., 2008. Alexander the Great's tombolos at Tyre and Alexandria, eastern Mediterranean. Geomorphology 100, 377-400.

- ^ Nir, Y., 1996. The city of Tyre, Lebanon and its semi‐artificial tombolo. Geoarchaeology 11, 235-250.

- ^ a b Carter, Terry; Dunston, Lara; Jousiffe, Ann; Jenkins, Siona (2004). lonely planet: Syria & Lebanon (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 345–347. ISBN 1-86450-333-5.

- ^ Sewell, Abby (29 May 2019). "Discover the best beaches in the Middle East". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ a b Rahhal, Nabila (5 July 2018). "The people's beaches". Executive Magazine. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "Protecting marine biodiversity in Lebanon". International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). 2 May 2012. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2014.

- ^ Hany El Shaer; Ms. Lara Samaha; Ghassan Jaradi (December 2012). "Lebanon's Marine Protected Area Strategy" (PDF). Lebanese Ministry of Environment.

- ^ Kabboul, Tamarah (October 2019). "A Giant Dolphin Was Just Found Stuck Between Rocks on Tyre Shore". The961. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Sarraf, Maria; Croitoru, Lelia; El Fadel, Mutasem; El-Jisr, Karim; Ikäheimo, Erkki; Gundlach, Erich; Al-Duaij, Samia (2010). Croitoru, Lelia; Sarraf, Maria (eds.). The Cost of Environmental Degradation: Case Studies from the Middle East and North Africa. Washington D.C.: World Bank Publications. p. 93. ISBN 978-0821383186.

- ^ Reuters Staff (22 February 2021). "Oil spill off Israel reaches south Lebanese beaches". Reuters. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- ^ Mroue, Youssef (2010). Highlights of the Achievements and Accomplishments of the Tyrian Civilization and Discovering the Lost Continent. Pickering. pp. 9–34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Badawi, Ali Khalil (2008). Tyr - L'histoire d'une Ville. Tyre/Sour/Tyr: Municipalité de Tyr / Tyre Municipality / Baladia Sour. pp. 80–103.

- ^ Palmer, Edward (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. pp. 2.

- ^ Renan, Ernest, "Mission de Phénicie", Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1864

- ^ Sepp, J. N., "Meerfahrt nach Tyrus zur Ausgrabung der Kathedrale mit Barbarossa's Grab", Leipzig: Seemann, 1879

- ^ Jidejian, Nina (2018). TYRE Through The Ages (3rd ed.). Beirut: Librairie Orientale. pp. 13–17. ISBN 9789953171050.

- ^ Tahan, Lina G. (2017). "Trafficked Lebanese Antiquities: Can They Be Repatriated from European Museums?". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies. 5 (1): 27–35. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027. ISSN 2166-3548. JSTOR 10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027.

- ^ Le Lasseur, D., "Mission archéologique à Tyr.", Syria 3, 1–26, 116–33, 1922

- ^ Poidebard, A., "Un grand port disparu: Tyr. Recherches aeriennes et sous-marines, 1934-6", Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 29. Paris, 1939.

- ^ a b c Boschloos, Vanessa (January 2016). "Belgian archaeologists in Tyre (Lebanon): UNESCO Heritage, Phoenician Seals and Ancient Curses" (PDF). ResearchGate. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Chéhab, Maurice H., "Fouilles de Tyr IV, La nécropole", Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth 36, 1986

- ^ Chéhab, M., "Fouilles de Tyr: la nécropole", Bulletin du Musée de Beirut 35, Beirut, 1985

- ^ a b Noureddine, Ibrahim; Mior, Aaron (2018). "Archaeological Survey of the Phoenician Harbour at Tyre, Lebanon". Bulletin d'Archéologie et d'Architecture Libanaises. 18: 95–112 – via Academia.edu.

- ^ Abousamra, Gaby; Lemaire, André (2013). "Astarte in Tyre According to New Iron Age Funerary Stelae". Die Welt des Orients. 43, H. 2 (2). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (GmbH & Co. KG): 153–157. doi:10.13109/wdor.2013.43.2.153. JSTOR 23608852.

- ^ Badawi, Ali Khalil (2018). TYRE (4th ed.). Beirut: Al-Athar Magazine. pp. 62, 74, 102.

- ^ Loosley, Emma (n.d.). "The Church of Paulinus, Tyre". Architecture and Asceticism. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ A visit to the Museum... The short guide of the National Museum of Beirut, Lebanon. Beirut: Ministry of Culture/Directorate General of Antiquities. 2008. pp. 37, 39, 49, 73, 75. ISBN 978-9953-0-0038-1.

- ^ "Dignitaries attend launching of Tyre khan renovation plan". The Daily Star. 15 July 2003. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Koïchiro Matsuura; The Director-General of UNESCO (11 August 2006). "UNESCO Director-General Launches "Heritage Alert" for the Middle East". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- ^ a b Toubekis, Georgios (2010). "Lebanon: Tyre (Sour)". In Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer (Eds.), "Heritage at Risk: ICOMOS World Report hey a report 2008-2010 on Monuments and Sites in Danger" (PDF).. Berlin: hendrik Bäßler verlag, 2010, pg. 118.

- ^ Helga Seeden (2 December 2000). "Lebanon's Archaeological Heritage".

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "UNESCO World Heritage Centre - State of Conservation (SOC 2011) Tyre (Lebanon)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Mukhamdov, Anton (1 November 2018). "Tyre's historic sites in fight to stay above the water". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Goiran, J-P., et al., 2021, Evolution of Sea Level at Tyre During Antiquity, Bulletin d'Archéologie et d'Architecture Libanaises, Vol. BAAL 21, (p 305-317).

- ^ "Ancient Tyre". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ a b Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "UNESCO Beirut organizes a technical workshop on the conservation and restoration works of Baalbek and Tyre World Heritage sites". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 28 May 2024.

- ^ Freifer, Rana (10 December 2013). "$1 million Picasso on auction – Proceeds to finance projects in Beirut and Tyre". BusinessNews.com.lb. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Bishara, Hakim (21 May 2020). "A Son Gifted His Mother a Raffle Ticket, Winning Her a $1.1M Picasso Painting". HYPERALLERGIC. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ ABI AKL, Yara (29 May 2017). "Liban: Maha el-Khalil Chalabi, gardienne du patrimoine". L'Orient-Le Jour (in French). Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ Nehmeh, Rafah (12 March 2019). "Celebrating Phoenician Crafts At Les Ateliers De Tyr". Lebanon Traveler. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Joshua 19:29

- ^ 2 Samuel 5:11, 1 Kings 5:1, and 1 Chronicles 14:1

- ^ Dever 2005, p. 97; Mendels 1987, p. 131; Brand & Mitchell 2015, p. 1538

- ^ Psalm 83:3–8

- ^ Isaiah 23

- ^ Joel 3:4–8

- ^ Ezekiel 26–28

- ^ Amos 1:9–10

- ^ Zechariah 9:3–4

- ^ Matthew 15:21; Mark 7:24

- ^ Mark 3:8; Luke 6:17

- ^ Matthew 11:21–23

- ^ Acts 12:19–24

- ^ Acts 21:1–7

- ^ Revelation 18

- ^ "Tyre Region of Europa". NASA EUROPA Clipper. 7 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d Stoughton, India (8 August 2016). "Championing culture in Lebanon's south". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ a b Hélou, Nelly (2016). "Le festival international de théâtre du Liban à Nabatieh : semer la culture et la joie". Agenda Culturel. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b c "Kassem Istanbouli re-opens the Rívoli Cinema". Al-Ghorba. April 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Monzer, Hiba (5 October 2018). "Promoting culture of peace through arts". United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ Istanbouli, Kassem (n.d.). "Cinema Rivoli". Tiro Association for Arts. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Majida al-Roumi ignites Jounieh with an evening of patriotic songs". The Daily Star. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Burkhalter, Thomas (2013). Local Music Scenes and Globalization – Transnational Platforms in Beirut. New York: Routledge. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-1138849716.

- ^ Rachidi, Soukaina (24 March 2019). "Fairuz and the Rahbani Brothers: Musical Legends Who Shaped Modern Lebanese Identity". Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Makarem, Racha (4 November 2010). "Fairuz: the voice of Lebanon". The National. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b Sarhan, Aladdin (29 May 2013). "I Believe that Several Paths Lead to God". Qantara.de. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Ġāzī Qahwaǧī". data.bnf.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Henoud, Carla (6 July 2002). "Femmes...Maha el-Khalil Chalabi, un combat incessant pour Tyr". L'Orient - Le Jour (in French). Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ Lebanon: The Official Guide. Paravision S.A.L. / Ministry of Tourism. n.d. p. 119. ISBN 978-9953002880.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Le Centre de Lecture et d'Animation Culturelle de Tyr – Sud Liban". MEDiakitab. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ "Kassem Istanbouli". Home New Home. 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ "About". Tiro Association for Arts. n.d. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ Ghali, Maghie (30 August 2018). "Bringing culture to your doorstep". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ "Peace Bus wheels out art and culture in south Lebanon". United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon. 7 September 2018. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Enders, David (5 September 2017). "Meet the Lebanese man trying to reopen cinemas closed by war". The National. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ^ Mottram, James (24 October 2019). "'Manara' sheds light on problems in Lebanese culture". The National. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- ^ Gharbieh, Hussein M. (1996). Political awareness of the Shi'ites in Lebanon: the role of Sayyid 'Abd al-Husain Sharaf al-Din and Sayyid Musa al-Sadr (PDF) (Doctoral). Durham: Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham.

- ^ a b Leichtman, Mara (2015). Shi'i Cosmopolitanisms in Africa: Lebanese Migration and Religious Conversion in Senegal. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 26, 31, 51, 54, 86, 157. ISBN 978-0253015990.

- ^ Norton, Augustus Richard (2014). Hezbollah: A Short History. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0691160818.

- ^ Marusek, Sarah (2018). Faith and Resistance: The Politics of Love and War in Lebanon. London: Pluto Press. pp. 127–150. ISBN 978-0745399935.

- ^ "The vision of the University". Islamic University of Lebanon. n.d. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 29 February 2020.

- ^ Abi Raad, Doreen (29 May 2020). "Lebanon's 'Pillar' of Catholic Education at Risk of Collapsing". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ "Harvard-bound Ismail Ajjawi an inspiration to fellow UNRWA students". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). 30 August 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Avi-Yonah, Shera S.; Franklin, Delano R. (27 August 2019). "Incoming Harvard Freshman Deported After Visa Revoked". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ "Freshman Previously Denies Entry to the United States Arrives at Harvard". The Harvard Crimson. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ https://lub-anan.com/المحافظات/الجنوب/صور/صور/المذاهب/

- ^ https://lub-anan.com/المحافظات/الجنوب/صور/صور/المذاهب/

- ^ "Lebanon - POPULATION". www.country-data.com.

- ^ "Bishop of Tyre: Christians in Lebanon have become a minority in their country". www.asianews.it.

- ^ Roberson, Ronald (28 July 2017). "The Eastern Catholic Churches 2017" (PDF). Catholic Near East Welfare Association (CNEWA). pp. 4, 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ^ "El Buss Camp". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). n.d. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "Burj Shemali Camp". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). n.d. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ a b "Rashidieh Camp". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). n.d. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- ^ "CASE STUDY OF AN UNREGULATED CAMP: JAL AL BAHAR, SUR, LEBANON". Refugee Camp studies. 3 October 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ^ Perdigon, Sylvain (October 2015). ""For Us It Is Otherwise": Three Sketches on Making Poverty Sensible in the Palestinian Refugee Camps of Lebanon". Current Anthropology. 56 (S11 (Volume Supplement)): S88–S96. doi:10.1086/682354. S2CID 141892419.

- ^ Vohra, Anchal (27 April 2019). "Dozens of Syrian refugees evicted in Lebanon anti-pollution drive". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Ayoub, Joey (14 November 2019). "The Lebanese revolution must abolish the kafala system". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Ethiopian domestic worker commits suicide in Tyre". The Daily Star. 7 April 2014. Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Harake, Dani; Kuwalti, Riham (31 May 2017). "Maachouk Neighbourhood Profile & Strategy, Tyre, Lebanon" (PDF). reliefweb. UN HABITAT Lebanon. pp. 2, 25–26. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Akleh, Tony (6 August 2020). "Beirut port: irreplaceable importance in the middle of Lebanon's geography". Arabian Business. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Zoghaib, Henri (2004). lebanon – THROUGH THE LENS OF MUNIR NASR. Beirut: Arab Printing Press sal. p. 74. ISBN 9789953023854.

- ^ El-Ghoul, Adnan (13 September 2004). "Wooden-boat makers in Tyre struggle to survive". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Alieh, Yassmine (6 February 2019). "Tyre, Hasbaya, Marjayoun are top property destinations". BusinessNews.com.lb. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- ^ Butt, Gerald (28 October 2019). "Lebanon's gas hopes threatened by corruption". PETROLEUM ECONOMIST. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Fifa suspends Lebanese FA". BBC Sport. 8 July 2001. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Rabih Ataya – Player Info". Global Sports Archive. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Nassar Nassar – Player Info". Global Sports Archive. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "El Corresponsal de Medio Oriente y Africa – Málaga recupera su pasado fenicio". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org.

- ^ "Capitains Nemo". cts.perseids.org.

- ^ "Saint Christina of Tyre (July 24)". Official website of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of Australia, New Zealand and the Philippines. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634–1099. Cambridge University Press. pp. 369–370. ISBN 978-0-521-59984-9.

- ^ "Bilal Najdi - Soccer player profile & career statistics - Global Sports Archive". globalsportsarchive.com. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Brand, Chad; Mitchell, Eric (November 2015). Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary. B&H Publishing Group. pp. 622–. ISBN 978-0-8054-9935-3.

- Dever, William G. (2005). Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2852-1. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Mendels, D. (1987). The Land of Israel as a Political Concept in Hasmonean Literature: Recourse to History in Second Century B.C. Claims to the Holy Land. Texte und Studien zum antiken Judentum. J.C.B. Mohr. ISBN 978-3-16-145147-8. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Illustrated Bible Dictionary". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Illustrated Bible Dictionary". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

Further reading

[edit]- Bikai, Patricia Maynor. The Pottery of Tyre. Warminster: Aris and Phillips, 1978.

- Bullitt, Orville H. Phoenicia and Carthage: A Thousand Years to Oblivion. Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1978.

- Joukowsky, Martha, and Camille Asmar. The Heritage of Tyre: Essays On the History, Archaeology, and Preservation of Tyre. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co., 1992.

- Woolmer, Mark. Ancient Phoenicia: An Introduction. London: Bristol Classical Press, 2011.

External links

[edit]- 360 Panorama of Tyre's Archeological Site

- Lebanon, the Cedars' Land: Tyre

- photo 2u

- Tyre entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith with picture of Tyrian silver shekel.

- Alexander's Siege of Tyre at World History Encyclopedia by Grant Nell

- American University of Beirut (AUB) Museum team discovers first Phoenician Temple in Tyre; only complete one in Lebanon

- Mission archéologique de Tyr in French

- Tyre, Lebanon

- Populated places in Tyre District

- Shia Muslim communities in Lebanon

- Sunni Muslim communities in Lebanon

- Populated coastal places in Lebanon

- Mediterranean port cities and towns in Lebanon

- 28th-century BC establishments

- Amarna letters locations

- Archaeological sites in Lebanon

- Coloniae (Roman)

- Former islands

- Hebrew Bible cities

- Phoenician cities

- Phoenician sites in Lebanon

- Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC

- Roman sites in Lebanon

- States and territories disestablished in the 6th century BC

- States and territories established in the 14th century BC

- Torah cities

- Tourism in Lebanon

- Tourist attractions in Lebanon

- World Heritage Sites in Lebanon

- Former kingdoms