Rice production in the United States

Rice production is the fourth largest among cereals in the United States, after corn, wheat, and sorghum. Of the country's row crop farms, rice farms are the most capital-intensive and have the highest national land rental rate average. In the United States, all rice acreage requires irrigation. In 2000–09, approximately 3.1 million acres in the United States were under rice production; an increase was expected over the next decade, to approximately 3.3 million acres.[1] USA Rice represents rice producers in the six largest rice-producing states of Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Texas.[2][3]

Historically, rice production in the United States was connected to agriculture using enslaved labor in the American South, first planting African rice and other kinds of rice in the marsh areas of Georgia, South Carolina, and later in the Louisiana territory and Texas, frequently in southern plantations. For some regions, this became an important profitable cash crop during the 18th and 19th centuries. In the 20th century, rice production was introduced to California, Arkansas, and the Mississippi Delta in Louisiana. Contemporary rice production in the United States includes African, Asian, and native varieties from the Americas.

Because of rice's long history in the United States, some regions, especially in the American South, have traditional dishes that include rice, such as "Hoppin' John", red beans and rice, and jambalaya. These food traditions have created widely recognized brands, such as Ben's Original.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

African rice (a separate species from Asian rice, originally domesticated in the inland delta of the Upper Niger River)[4][5] was introduced first to the United States in the 17th century. However Carolina rice, a sample of Patna rice was the first rice to be domestically consumed and later adopted by masses in America. Patna Rice was already highly popular in Europe by this time and accounted for most of its rice imports. It is mentioned to have been under cultivation in Virginia as far back as 1609, although it is reported that one bushel of rice had been sent to the colony later, in the summer of 1671, on the cargo vessel William and Ralph. In 1685, a bag of Madagascar rice known as "Gold Seede" (Asian rice) was given to Dr. Henry Woodward. A tax law of 26 September 1691 had permitted payment of taxes by the colonists by way of rice and other commodities.[6] [7]

The colonies of South Carolina and Georgia prospered and amassed great wealth from Asian rice planting, based on the slave labor and knowledge obtained from the Senegambia area of West Africa and from coastal Sierra Leone. One batch of slaves was advertised as "a choice cargo of Windward and Gold Coast Negroes, who have been accustomed to the planting of rice." At the port of Charleston, through which 40% of all American slave imports passed, slaves from Africa brought the highest prices in recognition of their prior knowledge of rice culture, which was put to use on the many rice plantations around Georgetown, Charleston, and Savannah.[6] The enslavement of Africans from Senegambia and Sierra Leone was strategic, as these people were from regions that grew rice and would eventually lead to the development of successful rice industries in many states like South Carolina.[8]

Enslaved Africans cleared the land, diked the marshes and built the irrigation system, skimming the freshwater layer off the high tide, flushing the fields, and adjusting the water level to the development stage of the rice. Rice was planted, hoed, and harvested with hand tools; plows and harvest wains could be pulled by mules or oxen wearing special shoes.[6] At first rice was milled by hand with wooden paddles, then winnowed in sweetgrass baskets (the making of which was another skill brought by slaves from Africa). The invention of the rice mill increased profitability of the crop, and the addition of water power for the mills in 1787 by American millwright Jonathan Lucas was another step forward.

Rice production was not merely unhealthy but lethal. One 18th-century writer wrote:[6]

If a work could be imagined peculiarly unwholesome and even fatal to health, it must be that of standing like the negroes, ankle and mid-leg deep in water which floats an ouzy mud, and exposed all the while to a burning sun which makes the air they breathe hotter than the human blood; these poor wretches are then in a furness of stinking putrid effluvia.

Inadequate food, housing, and clothing, malaria, yellow fever, venomous snakes, alligators, hard labour, and brutal treatment killed up to a third of Low Country slaves within a year. Not one child in ten lived to age sixteen. However, in the 1770s, a slave could produce rice worth more than six times his or her own market value in a year, so this high death rate was not uneconomical for their owners. Enslavers often stayed away from rice plantations during the summer, so slaves had more autonomy during these months.[10] Rice plantations could produce profits of up to 26 percent per year. Runaways, on the other hand, were a problem:[6]

I gave them a hundred lashes more than a dozen times; but they never quit running away, till I chained them together, with iron collars round their necks, and chained them to spades, and made them do nothing but dig ditches to drain the rice swamps. They could not run away then, unless they went together, and carried their chains and spades with them. I kept them in this way two years....

- — one overseer's method of controlling slaves, reported by fugitive slave Charles Ball

Most plantations were run on the task system, where a slave was given one or more tasks, estimated at ten hours' hard work, each day. After they had finished the tasks to the overseer's satisfaction, they could spend the remainder of the day as they chose, often on growing their food, spinning, sewing their clothes, or building their houses (slaves were typically supplied with nails and five yards of cloth per year). The task system, and the unwillingness of free people to live in rice-growing areas, may have led to the greater survival of African culture among the Gullah.[6]

In the country's early years, rice production was limited to the South Atlantic and Gulf states. For almost the first 190 years of rice production in the US, the principal producers were South Carolina and Georgia. Limited amounts were grown in North Carolina, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.[11]

19th century

[edit]

Rice was introduced into the southern states of Louisiana and east Texas in the mid-19th century.[12] Meanwhile, soil fertility in the east fell, especially for inland rice.[6]

Emancipation in 1863 freed rice workers. East-coast rice farming required hard, skilled work under extremely unhealthy conditions, and without slave labour, profits fell. Increasing automation in response came too late, and a series of hurricanes that hit Carolina in the late 1800s and damaged levees put an end to the industry. Production shifted to the Deep South,[13] where the geography was more favourable to mechanization.[11]

These events can be seen in rice production statistics. In 1839, the total production was 80,841,422 pounds, of which 60,590,861 pounds were grown in South Carolina and 12,384,732 pounds in Georgia. In 1849, cultivation reached 215,313,497 pounds.[14] Between 1846 and 1861, annual rice production in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia averaged more than 105 million pounds of cleaned rice, with South Carolina producing more than 75 percent. By 1850, South Carolina's cash crop was rice which was on 257 plantations producing 159,930,613 pounds and at its highest there were 150,000 acres of swamps under cultivation.[8]

At the census of 1870, after emancipation, the production of rice decreased to 73,635,021 pounds. In 1879, the total area devoted to rice was 174,173 acres, and the total production of clean rice was up again to 110,131,373 pounds. A decade later, the total area devoted to rice cultivation was 161,312 acres, and the total production of clean rice equaled 128,590,934 pounds; this represented a 16.76 percent increase in the amount produced, with a decrease of 7.38 percent in the area under cultivation.[14]

Between 1890 and 1900, Louisiana and Texas increased rice crop acreage to such an extent that they produced almost 75 percent of the country's product. Between 1866 and 1880, the annual production of the three states averaged just under 41 million pounds, of which South Carolina produced more than 50 percent. After 1880, their average annual production approximated 46 million pounds of cleaned rice, of which North Carolina produced 5.5 million, South Carolina 27 million and Georgia 13.5 million pounds.[11]

The rice industry in Louisiana began around the time of the Civil War. For a number of years, production was small, but during the 1870s the industry began to assume large proportions, averaging nearly 30 million pounds for the decade and exceeding 51 million pounds in 1880. In 1885, the production reached 100 million pounds, and in 1892, 182 million pounds. The great development of the rice industry in Louisiana after 1884 resulted from the opening up of a prairie region in the southwestern part of the state, and the development of a system of irrigation and culture which made possible the use of harvesting machinery similar to that used in the wheat fields of the Northwest, greatly reducing the costs of production. In 1896, yield from the Louisiana rice fields, where harvesting machinery was used, was good. However the milling process was not successful commercially in some rice varieties. The loss due to the milling process was considerable, particularly of the unbroken rice in the "head rice" variety.[11]

20th century to present

[edit]

Rice was established in Arkansas in 1904, California in 1912, and the Mississippi Delta in 1942.[3] Rice cultivation in California in particular started during the California Gold Rush. It was introduced primarily for the consumption of about 40,000 Chinese laborers who were brought as immigrants to the state; only a small area was under rice cultivation to meet this requirement. However, commercial production began only in 1912 in the town of Richvale in Butte County.[15] Since then, California has cultivated rice in a big way, and as of 2006, its production of rice was the second largest in the United States.[16]

Production

[edit]

Rice culture in the southeast became less profitable with the loss of slave labor after the American Civil War, and it finally died out just after the turn of the 20th century. Today, people can visit the historic Mansfield Plantation in Georgetown, South Carolina, the state's only remaining rice plantation with the original mid-19th century winnowing barn and rice mill. The predominant strain of rice in the Carolinas was from Africa and was known as "Carolina Gold". The cultivar has been preserved and there are current attempts to reintroduce it as a commercially grown crop.[17]

In 1900, the annual production of rice in the US was approximately half the annual consumption. The two principal varieties of lowland rice which were cultivated in the Atlantic States were the "gold seed rice" and white rice, which were the original rice varieties introduced into the US. Gold seed rice was notable for the larger yield of the grain. It thus practically superseded white rice which was cultivated in the earlier years. Experiments with upland rice demonstrated that it could grow over large areas of the country but the crop's yield and quality are inferior to lowland rice produced by irrigation methods.[11]

Since then, California has cultivated rice on a large scale, and as of 2006 its production was the second largest state,[16] after Arkansas, with production concentrated in six counties north of Sacramento.[18]

During 2012, the estimated rice production was 199 million cwt, or 19.9 billion lbs. This was a rise of 8% over the production of 2011. The harvested area also recorded a rise from 2.68 million ha in 2012 to 2.7 million ha in 2013. Another record was of the yield during 2012 recorded at 7,449 pounds per acre, higher than the 2011 yield by 382 pounds per acre.[19]

Six states now account for over 99% of all rice grown in the US. These are the Rice Belt states (Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas), California and Missouri. As of 2003, Arkansas topped the list with a production level of 213 million bushels against a total production of 443 million bushels in the country, and the annual per capita consumption reported is in excess of 28 pounds.[20]

By state

[edit]Arkansas

[edit]

Texas

[edit]

Types of rice

[edit]

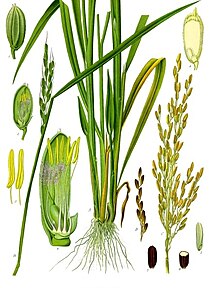

The earliest types grown in South Carolina were the African Oryza glaberrima and the prized "Carolina Gold," which is believed to originate in Southeast Asia but how it came to the US is unknown.[26]

After the total decline of rice cultivation in South Carolina, "Carolina Gold" is now cultivated in Texas, Arkansas and Louisiana.[6]

In California, production is dominated by short and medium-grain japonica varieties, including cultivars developed for the local climate, such as Calrose, which makes up as much as 85% of the state's crop. The broad classification of rice grown includes long-grain rice, medium-grain rice and short-grain rice.[27]

While more than 100 varieties of rice are now grown in the world, in the US 20 varieties of rice are commercially produced, primarily in the states of Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and California. Primary classifications of rice grown are the long, medium or short-grain type. The long-grain rice is slender and long, the medium-grain rice is plump but not round, and the short-grain rice is round. The forms of rice are brown rice, parboiled rice and regular-milled white rice.[20][28]

Domestically, 58% of rice in the US is used as food, while 16% is used in food and beer processing and 10% is used in pet food.[28]

Special varieties of rice, such as jasmine rice and basmati rice which are of the aromatic variety, are imported from Thailand, India, and Pakistan, as such varieties have not been evolved in the US; this demand for import is quite substantial and largely to meet the increasing population of the rice-eating ethnic community.[29]

Milling process

[edit]Harvested rice is subject to milling to remove the husk, which encloses the kernel. Before this process is started, the rice from the field is subject to a cleaning process to remove stalks and any extraneous material by means of special machinery. In the case of parboiled rice, a steam pressure process is adopted for milling. Rice drying.[30] The rice is then subjected to further processing to remove the hull and then polished. Brown rice is processed through a shelling machine which removes the hull. The resulting brown rice retains the bran layer around the kernel. In the case of white rice, the hull and the bran are removed, and the kernels polished.[20]

Exports

[edit]The first export of rice from Carolina was 5 tons in 1698, which rose to 330 tons by 1700 and jumped to 42,000 tons in 1770. Carolina rice was popularized in France by the renowned French chefs Marie Antoine Carême and Auguste Escoffier.[31] However, as a result of the abolition of slave labour, export from Carolina eventually ceased.[6]

While the rice production in the US accounts for about 2% of world production, its exports account for about 10% of all exports. The export is mostly of high-quality rice of the long and combined medium/short-grain varieties of rice. The type of rice exported is rough or unmilled rice, parboiled rice, brown rice, and fully milled rice. Exports to Mexico and Central America are mostly of the rough rice variety. Other countries to which the US exports rice include Mexico, Central America, Northeast Asia, the Caribbean, and the Middle East, Canada, the European Union (EU-27), and Sub-Saharan Africa.[29]

The exported variety is free of genetically enhanced (GE) rice. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) are the agreements under which the US exports its rice and this has resulted in an increase of exports from the country since the 1990s.[29]

Culture

[edit]

A popular custom observed on New Year's Day, by many Americans (mostly from the southern states) is the preparation and consumption of a rice cuisine called the "Hoppin' John". Since rice is associated with slave labor as their staple diet black eyed cow peas made in to a pulp by boiling; boiled yams and occasionally a small amount of beef or pork) it is eaten in the US on New Year's Day in the belief that it brings good luck since people who "eat poor New Year's Day, eat rich the rest of the year."[6]

The International Rice Festival is held every year in Crowley, Louisiana, on Friday and Saturday of the third weekend in October. It is the largest and oldest agricultural festival of Louisiana. The festival is a celebration of rice as a staple food and its economic importance in the world.[32] The tradition was set in 1927 as a Rice Carnival by Sal Right, a pioneer of the rice industry. However, the celebration of this festival in Crowley is also attributed to Harry D Wilson, Commissioner of Agriculture. It is also said that the festival was the idea of the Governor to celebrate the festival on the occasion of the silver jubilee of establishment of the city of Crowley on 25 October 1937.[33]

See also

[edit]- Wild rice

- Rice Belt

- Rice cultivation in Arkansas

- Texas rice production

- Tichnor Rice Dryer and Storage Building

- Hubbard Rice Dryer

- Koda Farms

- A.M. Bohnert Rice Plantation Pump

References

[edit]- ^ Baldwin, Katherine (April 2011). Consolidation and Structural Change in the U.S. Rice Sector. DIANE Publishing. pp. front cover, 11–. ISBN 978-1-4379-8478-1.

- ^ "USA Rice". USA Rice. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ a b Kulp, Karel; Ponte, Jr., Joseph G. (2000). Handbook of Cereal Science and Technology. Marcel Dekker. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-0-8247-8294-8.

- ^ Linares, Olga F. (2002-12-10). "African rice (Oryza glaberrima): History and future potential". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (25): 16360–16365. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916360L. doi:10.1073/pnas.252604599. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 138616. PMID 12461173.

- ^ Wang, Muhua; Yu, Yeisoo; Haberer, Georg; Marri, Pradeep Reddy; Fan, Chuanzhu; Goicoechea, Jose Luis; Zuccolo, Andrea; Song, Xiang; Kudrna, Dave; Ammiraju, Jetty S. S.; Cossu, Rosa Maria; Maldonado, Carlos; Chen, Jinfeng; Lee, Seunghee; Sisneros, Nick; de Baynast, Kristi; Golser, Wolfgang; Wissotski, Marina; Kim, Woojin; Sanchez, Paul; Ndjiondjop, Marie-Noelle; Sanni, Kayode; Long, Manyuan; Carney, Judith; Panaud, Olivier; Wicker, Thomas; Machado, Carlos A.; Chen, Mingsheng; Mayer, Klaus F. X.; Rounsley, Steve; Wing, Rod A. (2014-07-27). "The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication". Nature Genetics. 46 (9): 982–988. doi:10.1038/ng.3044. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 7036042. PMID 25064006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Rice and Slavery in America". Slavery in America Organization. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ "The History of U.S. Rice Production - Part 1". Louisiana State University Ag Center. November 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Garth, Hanna; Reese, ASHANTÉ (2020). "2 THE INTERSECTION OF POLITICS AND FOOD SECURITY IN A SOUTH CAROLINA TOWN". Black Food Matters: Racial Justice in the Wake of Food Justice. University of Minnesota Press. p. 66.

- ^ a b https://ricediversity.org/outreach/educatorscorner/documents/Carolina-Gold-Student-handout.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Garth, Hanna; Reese, ASHANTÉ (2020). "2 THE INTERSECTION OF POLITICS AND FOOD SECURITY IN A SOUTH CAROLINA TOWN.". Black Food Matters: Racial Justice in the Wake of Food Justice. University of Minnesota Press. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e Knapp, Seaman Ashahel (1900). Rice culture in the United States (Public domain ed.). U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 6–.

- ^ "Farm Raised Crawfish". Crawfish.com. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ http://www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-colonial/1875 [dead link]

- ^ a b United States. Census Office (1895). Reports on the statistics of agriculture in the United States: agriculture by irrigation in the western part of the United States, and statistics of fisheries in the United States at the eleventh census: 1890 (Public domain ed.). Government Printing Office. pp. 72–.

- ^ Lee, Ching (2005). "Historic Richvale – the birthplace of California rice". California Farm Bureau Federation. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved 10 June 2013.

- ^ a b "California's Rice Growing Region". California Rice Commission. Archived from the original on February 10, 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "Carolina Gold Rice Foundation". Carolina Gold Rice Foundation. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ^ Sumner, Daniel A. & Brunke, Henrich (September 2003). "The economic contributions of the California rice industry". California Rice Commission. Archived from the original on April 26, 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Crop Production: 2012 Summary" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b c "U.S. Rice Production". Riceland.com. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ Weller, Keith. Image Number K7577-1. USDA Agricultural Research Service Photo Library.

- ^ Arkansas Rice. 2011. Arkansas Rice Federation. http://www.arkansasricefarmers.org/arkansas-rice-facts/

- ^ a b Watkins, Bradley K., Merle M. Andres and Tony E. Windham, "An Economic Comparison of Alternative Rice Production Systems in Arkansas." Journal of Sustainable Agriculture Vol. 24. Issue 4 (2004): Pages 57-78

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service,"Quick Stats: Agricultural Statistics Data Base," http://www.nass.usda.gov/QuickStats (Retrieved on 2011-10-12)

- ^ Gates, John. "Groundwater Irrigation in the Development of the Grand Prairie Rice Industry, 1896-1950." The Arkansas Historical Quarterly Vol. LXIV. Issue 4 (2005): Pages 394-413

- ^ Pandolfi, Keith (5 November 2019). "The Story of Carolina Gold, the Best Rice You've Never Tasted". Serious Eats. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ "Medium Grain Varieties". California Rice Commission. Archived from the original on May 8, 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ a b "United States Department of Agriculture:Release No. 0306.06". U.S. RICE STATISTICS. August 2006.

- ^ a b c "Trade". Rice exports. USDA Economic Research Service. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Rice Drying and Storage | How to dry and store rice for farming". uaex.uada.edu. Retrieved 9 July 2024.

- ^ Barber, Dan (2014). The Third Plate: Field Notes on the Future of Food. Penguin. ISBN 9780698163751.

- ^ "About the Festival". Rice Festival.Com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ^ "Festival History". Rice Festival.com. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

Further reading

[edit]- Dethloff, Henry C. A history of the American rice industry, 1685-1985 (1988) online

- Gerber, James. "The Poetics of American Agriculture: The United States Rice Industry in International Perspective." Agriculture and Rural Connections in the Pacific (Routledge, 2017) pp. 345–368.

- Miller, Bonnie M. "Race and Region: Tracing the Cultural Pathways of Rice Consumption in the United States, 1680-1960." Global Food History 5.3 (2019): 183–203.

- Wailes, E. J., E. C. Chavez, and Alvaro Durand-Morat. "World and United States Rice Baseline Outlook, 2017-2027." Arkansas Rice Research Studies 2017: 411+ [Wailes, E. J., E. C. Chavez, and Alvaro Durand-Morat. "World and United States Rice Baseline Outlook, 2017-2027." Arkansas Rice Research Studies2017: 411. online].

- Wang, Xueyan, et al. "Dynamic changes in the rice blast population in the united states over six decades." Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 30.10 (2017): 803-812 online.

- Webb, B. D., et al. "Utilization characteristics and qualities of United States rice." Rice grain quality and marketing (IRRI, Manila, Philippines, 1985): 25–35. online