American Bank Note Company Printing Plant

| American Bank Note Company Printing Plant | |

|---|---|

View from Lafayette Avenue looking west | |

| |

| Alternative names | American Bank Note Company Building |

| General information | |

| Type | Printing plant |

| Architectural style | Gothic-inspired |

| Location | Hunts Point, Bronx, New York City |

| Address | 1201 Lafayette Avenue, Bronx, NY 10474 United States |

| Coordinates | 40°49′01″N 73°53′26″W / 40.81694°N 73.89056°W |

| Construction started | 1909 |

| Completed | 1911 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 6 |

| Floor area | 405,000 square feet (37,600 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Kirby, Petit & Green |

The American Bank Note Company Printing Plant is a repurposed printing plant in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx in New York City. The main structure includes three interconnected buildings.[note 1] The Lafayette wing, spanning the south side of the block, is the longest and tallest, incorporating an entrance at the base of a nine-story tower. The lower, more massive Garrison wing is perpendicular. These two were built first, and constitute the bulk of the complex. Prior to the American Bank Note Company purchasing the property, the land on which the printing plant was built had been part of Edward G. Faile's estate.

The plant was built in 1909–1911 by the American Bank Note Company contemporaneously with their corporate headquarters at 70 Broad Street, Manhattan. The design by Kirby, Petit & Green (who also designed the Broad Street building) incorporated advanced engineering ideas such as the sawtooth roof and large windows for improved lighting, unit drive electric motors in lieu of line shafts, and increased electrical capacity; layout was based on a design philosophy of specifying the production lines first, followed by the building which could enclose them. A small detached garage at the rear of the block was added in approximately 1911 and the Barretto wing was added to the east side of the property in 1912. Several building expansions took place between 1912 and 1928.

A wide variety of financial documents, including international currency, were printed at the plant. At one point, over five million documents were produced per day, including half the securities being traded on the New York Stock Exchange. Although the plant printed money for countries around the world, it was best known for producing currencies for countries in Latin America. The plant also housed a research department which worked to improve materials and processes to deter forgeries.

The plant was the target of a terrorist bombing in 1977 with the site chosen specifically because it was printing currency for Latin American countries. The facility was used by American Bank Note until about 1984 after which the property has changed hands several times, undergone a series of renovations, and been designated a New York City landmark. As of 2024[update], it has been subdivided, with major tenants including the John V. Lindsay Wildcat Academy Charter School and the New York City Human Resources Administration.

Previous land use

[edit]

Until the late 19th century, the land where the plant stands was part of the village of West Farms in Westchester County.[1] The area that is now the Barretto Street block was part of the 85-acre (34 ha)[2] estate of wealthy tea merchant Edward G. Faile, where the Faile Mansion (known as Woodside) was built in 1832.[3]

The area was annexed to New York City in 1874.[4] In 1904, the estate was sold to the Central Realty, Bond & Trust Company for about $1 million (equivalent to $33.9 million in 2023),[note 2] including 1,299 lots "bounded by Dongan Street, Intervale Avenue, Southern Boulevard, Longwood Avenue, Lafayette Avenue, Hunt's Point Road, Gilbert Place, and the Bronx River".[5] In September 1908, a portion of the estate comprising "over 400 lots" was acquired by the George F. Johnson's Sons Company, a real-estate developer building two-family houses in the Bronx.[6] In November of that year, 123 lots were resold to American Bank Note, including "all the property on the northerly side of Lafayette Ave, from Manida St. to the tracks of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad ... all the property on both sides of Garrison Ave, from Manida St. to Lafayette Ave ... all the property between these boundaries except eighteen lots on Manida Street ... upon which two-family houses are being erected."[7] In 1910, the size of the Barretto Street block was increased as a result of a land swap between American Bank Note and the city government. The block gained a strip of land on the northeast side of the property and Barretto Street was moved slightly north of its original location.[8]: 11

Land acquisition and construction

[edit]The American Bank Note Company was formed on April 29, 1858, when seven large engraving firms (Toppan, Carpenter & Co.; Rawdon, Wright, Hatch & Edson; Danforth, Perkins & Co.; Jocelyn, Draper, Welch & Co.; Wellstood, Hay & Whitney; Bald, Cousland & Co.; and John E. Gavit) merged.[9] The combined company's first printing plant was at Wall and William Streets, Manhattan, in a building which would later become the United States Custom House and eventually National City Bank.[10]: 41, 43 They moved to 142 Broadway in 1867 and to 86 Trinity Place in 1884.[11]: 15 By 1908 they had plants on Trinity Place, on Sixth Avenue, and other locations in Manhattan[12] as well as in Boston and Philadelphia.[13]

In 1908, American Bank Note built a new building at 70 Broad Street, Manhattan, into which they moved their administrative and sales offices. In parallel with this effort, the company was looking for a separate location into which they could move their production facilities; they felt that housing administration and production in separate locations would increase efficiency.[14]: 2 The search culminated in the 1908 purchase of a large tract of land including the Barretto Street block from George Johnson.[15] In his 1913 history of the Bronx, Harry Cook noted that "The choice of its present site in the Hunt's Point section of the Bronx was the result of a [thorough] canvas of all the available sections in Greater New York".[16]: 41 One factor in the site selection was proximity to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad line; discussions were held with the railroad to ensure they would be able to handle the plant's "considerable freight delivery needs" totaling 10,000 short tons (9,100 t) per year of paper and other supplies.[8]: 3

The sale closed on November 20, 1908. The New York Times wrote that they expected the Trinity Place plant would be sold once the new Bronx facility was in operation. The total cost for the project was to be greater than $2 million ($67.8 million in 2023), with American Bank Note having a current capitalization of $10 million ($339 million in 2023).[note 2] Wages for most employees were to be $40 to $75 ($1400 to $2500 in 2023)[note 2] per week for "the highest class of skilled labor",[13] and construction plans included housing for the workers. Robert E. Simon of the Henry Morgenthau Company estimated that within two or three years of American Banknote's relocation, taxable values in the neighborhood would increase by $5 million ($170 million in 2023).[note 2][13] It was anticipated that 2,500 to 3,000 people would be employed initially, with the plant being sized to accommodate growth to 5,000.[15]

American Bank Note engaged the architecture firm of Kirby, Petit & Green (who also designed the company's downtown headquarters) for the building design.[17] Kirby, Petit & Green designed several printing plants around this time, including San Francisco's Hearst Building in 1908, housing the printing plant for the San Francisco Examiner, and a plant in Garden City, Long Island, for the Country Life Press in 1910.[14]: 2 The firm was preparing preliminary plans before the land purchase was completed.[13]

Design evolution

[edit]The New York Times reported on May 23, 1909, that construction was "about ready to begin",[15] describing a design which was abandoned before the end of that year.[8]: 3 This initial design included a long wing[note 1] running the length of the Lafayette Avenue frontage, where the engraving and lithographing departments would be housed. Two additional wings, running along the Tiffany and Garrison sides of the property, would enclose a storage building in the V-shaped central area. Each of these wings was an independent structure, with all four buildings interconnected.[15] By this time, a large-scale model had already been constructed based on this initial design although the Times said that the design represented by the model might still "be subjected to some minor changes".[15]

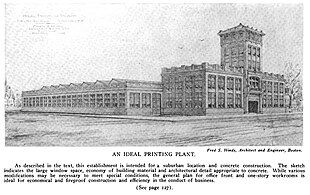

A 1909 article published in Printing Art (reprinted in The Cement Age), described a prototype design for "an ideal printing plant".[18] The final design appears to have been influenced by this, as the constructed plant more closely resembles this "ideal" design than the original one shown in the New York Times article.[8]: 3 The design change was driven by the tenets of the newly emerging field of industrial engineering; rather than build standardized buildings which were then filled with machines, the machine spaces were designed to optimize production, and then the buildings were designed to enclose the production lines.[8]: 3

The original plan provided for a single entrance to the building complex, about which the Times wrote, "This, of course, is made necessary by the character of much of the company's business; but an entire block of buildings without a rear entrance or a side door is certainly entitled to rank as a structural novelty."[15] In contrast to the Times, the Landmarks Preservation Commission noted in their 2008 report that this single-entrance configuration, "though characteristic of nineteenth-century industrial design, was not particularly adapted to the needs of the American Bank Note Company operation."[14]: 3 As built, the Tiffany Street entrance is recessed behind four arched openings on the west façade, which also includes a loading dock spanning most of the west side of the building.[8]: 8

Initial configuration

[edit]

The initial 1911 construction consisted of only two buildings: the long and tall but narrow office wing along Lafayette Avenue, and the large press building at right angles to it.[8]: 4 Several additions were made over the next few years. Typical of printing plants, the buildings have an open plan, concrete floors, and high ceilings to accommodate large presses.[19] Column spacing is 40 feet (12 m) in places, with floors typically rated for 120 pounds per square foot (5.7 kPa) live loads. Some areas have 21-foot (6.4 m) ceilings.[20]: overview/specifications The buildings sit on a roughly pentagonal block bordered by Garrison Avenue, Tiffany Street, Lafayette Avenue, and Barretto Street, with Barretto curving to form two sides.[19][20] In 1913, Harry Cook described the plant as "mammoth".[16]: 41 The New York Times wrote in 1992 that the site had an "unabashedly industrial look"[19] and noted that Architecture & Building Magazine had referred to its "arsenal-like appearance with a pervading sense of strength and security".[19] The site included 200 presses, a private restaurant, hospital, laundry, machine and carpenter shops, and laboratories where special inks were formulated.[8]: 3

The electrical requirements were exceptional for the day, and required special provisioning by the New York Edison Company. In addition to lighting, loads included 500 motors (compared to 300 at the Trinity Place plant) driving the presses, pumps, and other machinery. The switchgear was in the basement.[11] The plant was designed to use individual electric motors to drive each press ("unit drive"), as opposed to the drive line shafting system in common use. Unit drive was an advanced technology for the time, only becoming widespread in the 1920s. The design of the building included a large amount of conduit and wiring to support the motors' electrical feeds.[8]: 4 and 11, note 27

The Lafayette wing is a tall but narrow building which originally contained offices and workrooms for plate preparation; the façade runs the full length of the Lafayette Avenue frontage, almost 465 feet (142 m).[8]: 6 In the center of the block is a nine story tower. As Lafayette Avenue slopes down to the west, the left-most portion of the building exposes several basement levels to the façade.[8]: 6–7 The exterior is brick, with a structural framework of steel, allowing for wide unbroken arches filled with glass. It was originally constructed as three stories, three bays deep, with large windows topped by arches on the third story.[8]: 6–7 The use of round arches and recessed brick spandrels were common in New York City industrial architecture of the late 19th century, evoking the German Rundbogenstil style of the 1830s and 1840s.[8]: 4 Although the building used modern incandescent and arc lighting,[21] the large windows also allowed daylight, necessary for visual inspection of detailed color printing work, to flood into the building. The steel framework allowed three times the window area as would have been possible in an all-brick structure.[21]

A three-story printing press building (now known as the Garrison wing) is at right angles to the Lafayette wing; it has larger open spaces, heavier floor slabs, and taller ceilings to accommodate the presses. The lower floor of this building included a vault for storing over 130,000 printing plates. The presses were on the upper floor; the saw-tooth roof incorporated many windows to supply natural illumination for inspecting plates and printed documents.[8]: 4 The saw-tooth roof design had long been used in England because it admitted glare-free light through its north-facing windows but had been avoided in North America due to concerns about supporting snow loads, leakage, and condensation. It was only in the early part of the 20th century that engineering improvements made this type of roof practical in colder climates.[8]: 11, footnote 20

The area to the west of the press building, along Tiffany Street and Garrison Avenue, originally had manicured lawns, a curved driveway, and a pedestrian walk flanked by lampposts. The lawns have since been turned into a paved parking lot, and most of the lampposts have been removed.[8]: footnote 36

Subsequent additions

[edit]In 1910, a detached garage designed by Kirby, Petit & Green was built at the corner of Garrison Avenue and Barretto Street. The garage, expanded to twice its original size in 1928 to provide space for ink production,[8]: 4 [22] is now known as the North Building.[20] In 1912, architect H. W. Butts added a single-story addition along the Barretto Street side of the property to hold a laundry and pulp mill,[8]: 4 estimated to cost $12,000 ($380,000 in 2023).[23][note 2] In 1925, a fourth story, only two bays deep, was added to the top of the Lafayette building, using materials that closely matched the style of the original.[8]: 6–7 The Barretto addition was raised to three stories in 1928, by architect Oscar P. Cadmus, providing space for additional presses and a machine shop.[8]: 4 [21] In the 1928 configuration, the buildings total 405,000 square feet (37,600 m2) of floor space, occupying a 178,000 square foot (16,500 m2) block.[20]

In addition to the buildings on the landmark block, American Bank Note developed other properties in the immediate area. In 1913, an employee welfare and research building was erected on Lafayette Avenue, on the other side of Barretto Street, also designed by H. W. Butts. A distribution center was added in 1925 and a paper storage warehouse in 1949. These additional buildings are mentioned (with their exact location and current disposition unspecified) in the Landmarks Preservation Commission report of 2008, but explicitly excluded from the landmark designation.[8]: 5

Operations

[edit]

In the 1960s, the plant was processing over 5 million pieces of paper a day, and printing half of the securities of the New York Stock Exchange.[17] Production included bank notes, postage and revenue stamps, stock and bond certificates, checks, traveler's checks, letters of credit,[8]: 2 lottery tickets,[24] and food stamps.[19] Although the plant printed money for 115 countries around the world, it was best known for producing currencies for Latin America, including Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Haiti, and Cuba.[24] The printing operation was organized into several divisions. Stocks, bonds, and postage stamps were handled by the engraved currency and steel plate divisions. A separate typographic division produced catalogs, booklets, folders, maps, railroad tickets and marketing materials for railroads, steamship lines and others.[8]: 4 The plant produced its own special rag paper as well as the boxes used for shipping its completed products. Printed materials were first wrapped in paper, then encased in metal containers which were sealed with solder to make them waterproof, then inserted into the tightly fitting custom boxes.[25]: 304

The company employed, according to New York Times columnist Meyer Berger, the world's most skilled engravers who served apprenticeships of ten years or longer. Some came from families which had been in the business for three or four generations. In 1958, the chief engraver was Will Ford, who had been with the company for 46 years.[25]: 304 In 1963, there were 33 engravers on staff; they employed a house style favoring "folded robes, bare-chested men, and half-naked women who seem to be a cross between a Wagnerian soprano and the White Rock nymph." This was driven by stock exchange regulations which required stock certificates to include an image of "a human figure with visible areas of flesh" as these, along with the details of folded robes, were considered the hardest for a counterfeiter to duplicate.[26]

The company prided itself on having the best-equipped plant and most advanced research program in the industry, as well as employing the finest designers, engineers, and printers to whom it offered an advanced employee welfare program.[14]: 2 An unusual job title at the company was counterfeiter; the job entailed attempting to produce copies of the company's own products.[19][10]: 69 When attempts were successful, better engraving, paper, or inks were incorporated into the products, to increase the difficulty of fraudulently reproducing the documents.[19][25]: 305 The counterfeiting office was in the tower (behind locked doors). One official counterfeiter was Will Ford's father, William F. Ford.[25]: 304

Physical security included counting each piece of paper 33 times as it progressed from raw material to finished product. Items which failed quality inspections were burned in a furnace. A high level of security was necessary not just to prevent theft, but also to keep from leaking information about jobs. Events such as stock splits or issuance of bonds could involve orders for printing new certificates months in advance of the announcement; these print jobs were closely guarded secrets to prevent untimely disclosure of customers' plans.[26]

One of the company's less successful ventures was playing cards, which they produced for six years starting in 1908. Although the company's financial documents were of the finest quality their playing cards were not, lacking an opaque inner layer, thus allowing the face of a card to be read from the back if held in a strong light. The playing card business was sold to the Russell Playing Card Company in 1914.[27]

Bombing

[edit]On March 20, 1977, the complex was damaged by a bomb planted by the FALN, a Puerto Rican terrorist group which had chosen to attack the plant because of its role in what they deemed "capitalistic exploitation".[28] The explosive device, placed near the Lafayette Avenue entrance, broke windows as high as the fourth floor. This was one of two FALN attacks that day, the other being to the FBI Manhattan headquarters, where one person received minor injuries.[29] A letter from the FALN claiming responsibility stated that the plant was targeted as a symbol of "Yanki repression and exploitation":[30]

The American Bank Note Company for being one of the chief administrator's in the exploitation of the World's Working Class. For printing the stocks and bonds that decide which families will eat and live well and which one's will starve and die. This company is also the printer of the currency of Several Latin American countries, Mexico and Guatemala being two of them. This company has the economic power to control the flow of currency in all Latin American countries. Giving absolute unilateral monetary control to American Corporations.

— FALN Central Command

These were the fiftieth and fifty-first attacks attributed to the group in the previous three years.[29] The next day, a second bomb threat against the plant was phoned into the Daily News. This turned out to be a hoax by a local resident who was distraught over personal issues. The man drove up to the plant while the police were sifting through rubble from the previous day's attack, announced that he had a hand grenade, and dropped it. The grenade failed to explode and was found to be a harmless practice device.[31]

Post–Bank Note

[edit]By 1984 or 1985 (sources differ), with the plant having only about 500 employees, American Bank Note moved their printing facilities to a new site in Blauvelt, New York.[8]: 6 [19][32] In 1985, the site was purchased by Walter Cahn and Max Blauner who repurposed it as the Bronx Apparel Center. The purchase and renovation costs totaled $8.3 million ($23.5 million in 2023)[note 2] The center occupied 146,000 square feet (13,600 m2) (about one third of the site), housing several tenant companies in the clothing and fabric industry.[33] The Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance also had space in the building during this time.[34] Other tenants included a wine cellar and a homeless shelter, along with art and photography studios.[21][35] Rents for the first tenants averaged $3.50 ($10.00 in 2023) per square foot.[33]

In 1997, the John V. Lindsay Wildcat Academy Charter School opened their Hunts Point campus in the complex, occupying the fourth through sixth floors[note 3] of the Lafayette wing.[36][37] The campus, which serves ninth and tenth grade students, includes the school's culinary internship program, the student-run JVL Wildcat Café and a hydroponics garden.[38][39] The space was renovated in 2005 using a $1 million grant from the Charles Hayden Foundation,[40] at which time they added a 5,000-square-foot (460 m2) "professional-grade" kitchen for their new culinary program.[37] The school renewed their lease in 2009, citing the 2005 improvements as a major factor in their decision to renew. The initial asking price was about $25 per square foot, although the final agreed rent was not made public.[40]

The Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance had their first home in the complex in 1998,[41] converting a previously vacant area into a 70-seat space for performances and workshops.[42] There they hosted the Arthur Aviles Typical Theatre dance company, with roots in Latino and LGBTQ cultures.[34][43][44] An anchor tenant with a long-term low-rent lease, they attracted other artists, who occupied spaces ranging from 600 square foot (56 m2) studios to entire floors.[42] The deal was catalyzed by The Point, a neighborhood community development group. The Point recruited several local artists to lease 400-square-foot (37 m2) studios[32] (another source says 600)[42] in the building for $375 ($700 in 2023) per month in exchange for the building's owners donating space to the dance company, which at the time was using The Point's building across the street. Aviles stated a desire to sign a ten-year lease in the building.[32]

In 2002, Lady Pink organized a group of female graffiti artists to paint an anti-war mural on a brick wall on the Barretto Street side of the property.[35][45]: 193 The group revisited the site for several years. In 2013, the wall was torn down by the site's new owners.[35]

The site was purchased by Taconic Investment Partners and Denham Wolf Real Estate Services in January 2008[46] for $32.5 million ($47.8 million in 2023); they invested another $37 million ($54.4 million in 2023)[note 2] on renovations.[47] Denham Wolf had a history of working with nonprofit and arts groups. The New York Times reported that "the new owners hope to make the building into a mecca for cultural groups that have been priced out of Manhattan".[46] Rents were estimated to be $20 to $30 per square foot, with the possibility of tax breaks reducing that number. At the time, comparable rents were in the mid $30s to $40 elsewhere in the Bronx and around $50 in midtown Manhattan.[46]

In 2010, the Sunshine Business Incubator began operations in the site, occupying 11,000 square feet (1,000 m2).[48] Small business and startups could rent small amounts of space (as little as just one desk), with access to shared facilities such as meeting rooms, and a reception area. Leases were available on a month-to-month basis.[49][50] The incubator targeted startups in the fields of new media, technology, biomedicine, healthcare and professional services.[49] In his 2014 State of the Borough address, borough president Ruben Diaz Jr. spoke of a "transformation" taking place in the Bronx, with economic growth from new businesses moving into the borough. He noted that the building housed the Sunshine Business Incubator which had "helped over 70 small companies take root through shared space and creative partnerships" as part of the "New Bronx".[51] Sunshine left the Bank Note building in 2014 with eight years left to run on its lease, and ceased operations completely in 2016.[52][53]

In 2013, the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance left the building when Taconic Investment Partners refused to extend their lease at the current rate, instead offering a one-year extension at double the rent. According to Academy co-founder Charles Rice-Gonzalez, Taconic "failed to keep a promise it made when it bought the building five years ago, to maintain the building's character as a mecca for the arts in Hunts Point".[54] Rice-Gonzalez also said that Taconic initially demanded a payment equal to six months rent and threatened legal action when the Academy moved out before the expiration of their lease, although they ultimately withdrew that demand.[54]

The New York City Human Resources Administration (HRA) signed a 20-year lease in 2013, intending to move into approximately half of the 400,000 square feet (37,000 m2) available space in the complex.[35] The move was completed in late 2014, combining existing offices at four locations to provide services to 1,700 clients daily in the areas of child support enforcement, home health care, Medicaid, food stamps, and HIV/AIDS assistance from this single location. Local 371, which represents the HRA employees, was opposed to the move, citing transportation issues and an inadequate number of bathrooms in the building. Bronx Community Board 2 was also opposed to the move with district manager Rafael Salamanca noting concerns over police presence and street lighting.[55]

Taconic Investment Partners sold the site to a partnership of two real estate investment firms, Madison Marquette and Perella Weinberg, for $114 million ($147 million in 2023)[note 2] in 2014.[47] As of 2024[update], Madison Marquette manages the building, which it markets as The BankNote.[20] In 2015, The Real Deal described the building as "one of the most architecturally distinctive office properties in the Bronx".[56]

Landmark status

[edit]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the site as a New York City landmark in 2008, observing that it was "one of nearly 200 factories and related sites that the Commission has named as landmarks since 2002, as part of its goal to preserve the City's industrial heritage."[17] A commemorative plaque installed in the Lafayette Avenue entrance lobby calls out the "crenellated tower", "massive brick piers", and "saw-tooth skylights" as significant architectural details.[57] Landmarks Commission Chairman Robert B. Tierney was quoted in the official announcement as saying:[17]

The plant is notable not only for its commanding presence in the neighborhood and from other vantage points in the Bronx, but also for the sweep of multistory arcades across the front façade and its nine-story medieval-style tower.

The announcement also cited "monumental arcades", the "Gothic-inspired details", and the "crenellated parapet of the central tower" as significant architectural features.[17] The building design emphasizes security by deliberately limiting access to a single entrance, despite having over 1,500 feet (460 m) of street frontage.[58] Benika Morokuma, of the Municipal Art Society, described the building in her testimony supporting the landmark designation:[59]

The facade of the plant is a clear example of the expressive factory design of the New York City around the turn of the twentieth century ... The austere and huge horizontal massing of the main part of the printing facility and the Gothic tower, which emphasizes the symmetry of the main façade on Lafayette Avenue, create an arsenal-like appearance and contribute to create sense of security that is closely associated with its line of business.

Transportation

[edit]The building is adjacent to the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad tracks (now the Hell Gate Line of the Northeast Corridor). When the plant was built, the railroad announced its intention to extend the sidings at Hunts Point and build a freight house to serve the site.[12] As of 2023[update], the Penn Station Access project is expected to provide Metro North service from a new Hunts Point station, which is expected to be completed by 2027.[60]

The site is one block away from Bruckner Boulevard with private parking adjacent to the Garrison wing.[20] The nearest subway stations are Hunts Point Avenue and Longwood Avenue, providing access to Manhattan via the 6 train. The Bx6 bus line runs along Hunts Point Avenue. Bicycle access is via the South Bronx Greenway.[61]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Sources variously refer to the main portion of the site as a single building with three wings (Lafayette, Garrison, and Barretto), or three distinct but interconnected buildings. The Landmarks Preservation Commission report, for example, uses both terms (p. 6: "Primary entry into the complex of buildings is via the west facade of the printing-press wing"). In this article, the terms wing and building are used interchangeably.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Most sources describe the Lafayette wing as having four floors plus several basement levels which are partially above ground at the west end of the downward-sloping block. Some modern sources refer to six floors.

References

[edit]- ^ A Guide to Historic New York City Neighborhoods: Hunts Point, The Bronx (PDF) (Report). Historic Districts Council. 2023. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ Towns of West Farms and Morrisania, Weschester Co., N.Y. (Map). New York: J.B. Beers & Co. 1872. Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved January 5, 2024 – via New York Public Library: Digital Collections (image id 56815703).

- ^ Brown, Henry Collins, ed. (1920). Valentine's Manual|Valentine's Manual of Old New York. Vol. 4. New York: Valentine's Manual Inc. p. 445. OCLC 4942908. Retrieved February 1, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hilton, Alexandra (May 27, 2017). "The Last County: The Bronx". NYC Department of Records & Information Services. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. New York: F. W. Dodge Corporation. October 22, 1904. p. 842. Retrieved February 3, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Big Bronx Operation: Thirty Two-Family Houses to be Built in the Hunt's Point Section". The New York Times. September 27, 1908. p. 12. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ "The Real Estate Market: Bronx". The Evening Post. New York. November 21, 1908. p. 20. OCLC 02260927. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x American Bank Note Company Printing Plant (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 5, 2008. Designation List 400, LP-2298. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Slone, George B (September 2015). "Sloane's Column: American Bank Note Co. – Centenary". U. S. Stamp News. 21 (9): 21–22. ISSN 1082-9423. EBSCOhost 109018814.

- ^ a b Griffiths, William H. (1959). The Story of American Bank Note Company (PDF). New York: American Bank Note Company. OCLC 774898443. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "The American Bank Note Company". The Edison Monthly. V (1): 14–17. June 1912. ISSN 2643-3737. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b "Manufacturing Plants: New York, N.Y." Construction News: Supplement to Engineering News. 60 (22). New York: The Engineering News Publishing Company: 191. November 26, 1908. Retrieved November 28, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d "Plant for 2,500 Men Moves to the Bronx". The New York Times. November 21, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "American Bank Note Company Office Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Designation List 283, LP-1955. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2018. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "Completing Plans for Immense Plant of American Bank Note Company". The New York Times. May 23, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Cook, Harry T.; Kaplan, Nathan J. (1913). The Borough of the Bronx 1639–1913. New York: Harry Cook. OCLC 806671. Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved September 18, 2023 – via Library of Congress.

- ^ a b c d e de Bourbon, Lisi (February 5, 2008). "Commission Mints Securities Printing Plant in The Bronx as New York City Landmark" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. No. 08-01. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Revised Ideal Printing Plant". Cement Age: A Monthly Magazine Devoted to the Uses of Cement. III (2): 127–130, plus photo on page 90. February 1909. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Streetscapes: The American Banknote Company Building; A Bronx Hybrid: Mill, or an Arsenal?". The New York Times. September 13, 1992. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f "The BankNote". Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Bady, David; Munch, Janet Butler; Lloyd, Ultan. "American Bank Note Company". Bronx Architecture. Lehman College Art Gallery. Archived from the original on May 2, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Notice of Public Hearing/Meeting (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 8, 2020. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved December 13, 2023.

- ^ "Building News: New York". The American Architect. 101. New York: 14. May 22, 1912. ISSN 2836-6638. Archived from the original on December 2, 2023 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Wallace, Mike (2017). Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199911462. Retrieved February 7, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Berger, Meyer (August 25, 2009). "December 29, 1958". Meyer Berger's New York. New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823223299. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Colclough, Frederic W. (March 22, 1963). "Making Money". Time Magazine. 81 (12): 86. ISSN 0040-781X. EBSCOhost 54211293.

- ^ "American Bank Note Company". The World of Playing Cards. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Claiborne, William (March 22, 1977). "Puerto Rican Group Claims Responsibility for N.Y. Blasts". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

one of the chief tools of capitalistic exploitation.

- ^ a b Kihss, Peter (March 22, 1977). "A.L.N. Claims Responsibility For 2 Bombings in New York City". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Committee on Government Reform (December 10, 1999). The FALN and Macheteros Clemency: Misleading Explanations, a Reckless Decision, a Dangerous Message (PDF) (Report). U. S. Government Printing Office. p. 450. House Report 106-488. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ^ "Threat of a 3d Bomb A Frightening Hoax". The New York Times. March 22, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c Siegal, Nina (April 10, 2000). "At a Long-Vacant Plant, Dabs of Life". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 27, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "Postings: South Bronx Venture Apparel Center". The New York Times. December 22, 1985. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ a b "Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance: BAAD". NYC-ARTS: The Complete Guide. Archived from the original on February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Wall, Patrick (October 9, 2013). "BankNote Building Tears Down Mural as Artists Leave and City Moves In". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Waldman, Amy (June 10, 1999). "School of the Second Chance; Turning Troubled Students Around at Wildcat High". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ a b Beekman, Daniel (May 15, 2009). "Wildcat Academy Banks on Banknote". The New York Post. ISSN 2641-4139. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Carr, Shanice (August 28, 2013). "Wildcat Academy Students Win National Gardening Award". The Hunts Point Express. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Culinary & Hydroponics". John V. Lindsay Wildcat Academy Charter School. Archived from the original on June 2, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Joe Hirsch (June 1, 2009). "Charter School Signs on to Stay in BankNote". The Hunts Point Express. Archived from the original on February 5, 2018. Retrieved February 4, 2018.

Hunts Point's historic BankNote building will continue to be home to the John V. Lindsay Wildcat Academy Charter School, at least until 2022.

- ^ "The Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance (BAAD) | Devex". www.devex.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c Gonzalez, David (April 27, 2014). "In New Home, Bronx Dance Academy Seeks to Step Up Its Presence". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ "As Real Estate Developers Challenge the Arts in the South Bronx, BAAD! the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance Moves from Hunts Point to a New Home to Keep the Arts Safe in the Bronx". BAAD! Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ "Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance (BAAD!)". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Archived from the original on August 20, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Gabriels, Jane de Lacy (January 2015). Choreographies of Community: Familias and its Impact in the South Bronx (PDF) (Thesis). Montreal: Concordia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c Cortese, Amy (May 18, 2008). "A New Stamp on a Vast Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Geiger, Daniel (September 15, 2014). "Architecturally Notable Bronx Building Sold for $114M". Crain's New York Business. ISSN 8756-789X. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ Hirsch, Joe (January 10, 2012). "BankNote Becomes Home to Business Incubator". The Hunts Point Express. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ a b "NYCEDC and Business Outreach Center Network Announce the Launch of BXL Business Incubator in the South Bronx". New York City Economic Development Corporation. January 22, 2015. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Chappatta, Brian (November 3, 2010). "Incubator Signs on at Historic Bronx Building". Crain's New York Business. ISSN 8756-789X. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Diaz, Ruben Jr. (February 20, 2014). "State of the Borough Address" (PDF). Bronx Borough President. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Sunshine Suites – Where Startups Grow Up". Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ^ Clarke, Katherine (October 10, 2016). "One of NYC's first co-working firms has shuttered its last location". The Real Deal. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Hirsch, Joe (October 28, 2013). "Legendary Dance Group Gone from BankNote". The Hunts Point Express. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Rosengren, Cole (November 2, 2024). "HRA Moves into Banknote Building". The Hunts Point Express. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ "SoBro's Best Bets". The Real Deal New York. April 1, 2015. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

one of the most architecturally distinctive office properties in the Bronx.

- ^ "The American Banknote Company Printing Plant Landmark Designation". Read the Plaque. Archived from the original on March 15, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ "American Bank Note Company Printing Plant Archives – CityLand". CityLand. March 15, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Testimony of the Municipal Art Society Before the Landmarks Preservation Commission" (PDF). January 15, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Penn Station Access". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on September 13, 2023. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Mayor de Blasio, NYCEDC, Congress Member Serrano, Speaker Mark-Viverito, Council Member Arroyo And Borough President Diaz Jr. Announce Opening of Randall's Island Connector". New York City Economic Development Corporation. November 16, 2015. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved February 19, 2020.