Alpha-1 antitrypsin

Alpha-1 antitrypsin or α1-antitrypsin (A1AT, α1AT, A1A, or AAT) is a protein belonging to the serpin superfamily. It is encoded in humans by the SERPINA1 gene. A protease inhibitor, it is also known as alpha1–proteinase inhibitor (A1PI) or alpha1-antiproteinase (A1AP) because it inhibits various proteases (not just trypsin).[5] As a type of enzyme inhibitor, it protects tissues from enzymes of inflammatory cells, especially neutrophil elastase.

When the blood contains inadequate or defective A1AT (as in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency), neutrophil elastase can excessively break down elastin, leading to the loss of elasticity in the lungs. This results in respiratory issues, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, in adults. Normally, A1AT is produced in the liver and enters the systemic circulation. However, defective A1AT may accumulate in the liver, potentially causing cirrhosis in both adults and children.

A1AT not only binds to neutrophil elastase from inflammatory cells but also to elastase on the cell surface. In this latter role, elastase acts as a signaling molecule for cell movement, rather than as an enzyme.[6] Besides liver cells, A1PI is also produced in bone marrow, lymphoid tissue, and the Paneth cells of the gut.[7]

Inactivation of A1AT by other enzymes during inflammation or infection can halt T cell migration precisely at the site of the pathological insult. This suggests that α1PI plays a key role in lymphocyte movement and immune surveillance, particularly in response to infection.[8] A1AT is both an endogenous protease inhibitor and an exogenous one used as medication. The pharmaceutical form is purified from human donor blood and is sold under the nonproprietary name alpha1–proteinase inhibitor (human) and under various trade names (including Aralast NP, Glassia, Prolastin, Prolastin-C, and Zemaira). Recombinant versions are also available but are currently used in medical research more than as medication.

Nomenclature

[edit]The protein was initially named "antitrypsin" because of its ability to bind and irreversibly inactivate the enzyme trypsin in vitro covalently. Trypsin, a type of peptidase, is a digestive enzyme active in the duodenum and elsewhere. In older biomedical literature it was sometimes called serum trypsin inhibitor (STI, dated terminology), because its capability as a trypsin inhibitor was a salient feature of its early study.

The term alpha-1 refers to the protein's behavior on protein electrophoresis. On electrophoresis, the protein component of the blood is separated by electric current. There are several clusters, the first being albumin, the second being the alpha, the third beta and the fourth gamma (immunoglobulins). The non-albumin proteins are referred to as globulins.

The alpha region can be further divided into two sub-regions, termed "1" and "2". Alpha-1 antitrypsin is the main protein of the alpha-globulin 1 region.

Another name used is alpha-1 proteinase inhibitor (α1-PI).

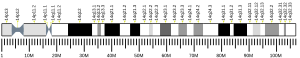

Genetics

[edit]The gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 14 (14q32.1).

Over 100 different variants of α1-antitrypsin have been described in various populations. North-Western Europeans are most at risk for carrying one of the most common mutant forms of A1AT, the Z mutation (Glu342Lys on M1A, rs28929474).[9]

Structure

[edit]A1AT is a single-chain glycoprotein consisting of 394 amino acids in the mature form and exhibits many glycoforms. The three N-linked glycosylations sites are mainly equipped with so-called diantennary N-glycans. However, one particular site shows a considerable amount of heterogeneity since tri- and even tetraantennary N-glycans can be attached to the Asparagine 107 (UniProtKB amino acid nomenclature). These glycans carry different amounts of negatively charged sialic acids; this causes the heterogeneity observed on normal A1AT when analysed by isoelectric focusing. Also, the fucosylated triantennary N-glycans were shown to have the fucose as part of a so-called Sialyl Lewis x epitope,[10] which could confer this protein particular protein-cell recognition properties. The single cysteine residue of A1AT in position 256 (UniProtKB nomenclature) is found to be covalently linked to a free single cysteine by a disulfide bridge.[10]

Function

[edit]A1AT is a 52-kDa serpin and, in medicine, it is considered the most prominent serpin; the terms α1-antitrypsin and protease inhibitor (Pi) are often used interchangeably.

Most serpins inactivate enzymes by binding to them covalently. These enzymes are released locally in relatively low concentrations where they are immediately cleared by proteins such as A1AT. In the acute phase reaction, a further elevation is required to "limit" the damage caused by activated neutrophil granulocytes and their enzyme elastase, which breaks down the connective tissue fiber elastin.

Besides limiting elastase activity to limit tissue degradation, A1PI also acts to induce locomotion of lymphocytes through tissue including immature T cells through the thymus where immature T cells mature to become immunocompetent T cells that are released into tissue to elevate immune responsiveness.[11]

Like all serine protease inhibitors, A1AT has a characteristic secondary structure of beta sheets and alpha helices. Mutations in these areas can lead to non-functional proteins that can polymerise and accumulate in the liver (infantile hepatic cirrhosis).

Clinical significance

[edit]

Disorders of this protein include alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, an autosomal co-dominant hereditary disorder in which a deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin leads to a chronic uninhibited tissue breakdown. This causes the degradation especially of lung tissue and eventually leads to characteristic manifestations of pulmonary emphysema.[12] Evidence has shown[13] that cigarette smoke can result in oxidation of methionine 358 of α1-antitrypsin (382 in the pre-processed form containing the 24 amino acid signal peptide), a residue essential for binding elastase; this is thought to be one of the primary mechanisms by which cigarette smoking (or second-hand smoke) can lead to emphysema. Because A1AT is expressed in the liver, certain mutations in the gene encoding the protein can cause misfolding and impaired secretion, which can lead to liver cirrhosis.

An extremely rare form of Pi, termed PiPittsburgh, functions as an antithrombin (a related serpin), due to a mutation (Met358Arg). One person with this mutation has been reported to have died of a bleeding diathesis.[14]

A liver biopsy will show abundant PAS-positive globules within periportal hepatocytes.

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been found to make autoantibodies toward the carbamylated form of A1AT in the synovial fluid. This suggests that A1AT may play an anti-inflammatory or tissue-protecting role outside the lungs. These antibodies are associated with a more severe disease course, can be observed years before disease onset, and may predict the development of RA in arthralgia patients. Consequently, carbamylated A1AT is currently being developed as an antigenic biomarker for RA.[15]

Analysis

[edit]A1AT has a reference range in blood of 0.9–2.3 g/L (in the US the reference range is expressed as mg/dL or micromoles), but the concentration can rise manyfold upon acute inflammation.[16]

The level of A1AT in serum is most often determined by adding an antibody that binds to A1AT, then using turbidimetry to measure how much A1AT is present. Other detection methods include the use of enzyme-linked-immuno-sorbent-assays and radial immunodiffusion.

Different analytical methods are used to determine A1AT phenotype. As protein electrophoresis is imprecise, the A1AT phenotype is analysed by isoelectric focusing (IEF) in the pH range 4.5-5.5, where the protein migrates in a gel according to its isoelectric point or charge in a pH gradient.

Normal A1AT is termed M, as it migrates toward the center of such an IEF gel. Other variants are less functional and are termed A-L and N-Z, dependent on whether they run proximal or distal to the M band. The presence of deviant bands on IEF can signify the presence of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. Since the number of identified mutations has exceeded the number of letters in the alphabet, subscripts have been added to most recent discoveries in this area, as in the Pittsburgh mutation described above.

As every person has two copies of the A1AT gene, a heterozygote with two different copies of the gene may have two different bands showing on electrofocusing, although heterozygote with one null mutant that abolishes expression of the gene will only show one band.

In blood test results, the IEF results are notated as in PiMM, where Pi stands for protease inhibitor and "MM" is the banding pattern of that patient.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin levels in the blood depend on the genotype. Some mutant forms fail to fold properly and are, thus, targeted for destruction in the proteasome, whereas others have a tendency to polymerise, being retained in the endoplasmic reticulum. The serum levels of some of the common genotypes are:

- PiMM: 100% (normal)

- PiMS: 80% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiSS: 60% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiMZ: 60% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiSZ: 40% of normal serum level of A1AT

- PiZZ: 10-15% (severe alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency)

- PiZ is caused by a glutamate to lysine mutation at position 342 (366 in pre-processed form)

- PiS is caused by a glutamate to valine mutation at position 264 (288 in pre-processed form)

Other rarer forms have been described; in all, there are over 80 variants.

Medical uses

[edit] | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Aralast, Zemaira, Glassia, others[17] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.919 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C2001H3130N514O601S10 |

| Molar mass | 44324.65 g·mol−1 |

| (verify) | |

Alpha-1 antitrypsin concentrates are prepared from the blood plasma of blood donors. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the use of four alpha-1 antitrypsin products derived from a human plasma: Prolastin, Zemaira, Glassia, and Aralast.[24][25][26][27][28][29] These products for intravenous augmentation A1AT therapy can cost up to $100,000 per year per patient.[31] They are administered intravenously at a dose of 60 mg/kg once a week; higher doses do not provide additional benefit although they can be used in anticipation of an interruption of weekly administration, such as for a vacation.[32]

Alpha1-proteinase inhibitor (Respreeza) was approved for medical use in the European Union in August 2015.[30] It is indicated for maintenance treatment, to slow the progression of emphysema in adults with documented severe alpha1-proteinase inhibitor deficiency (e.g., genotypes PiZZ, PiZ (null), Pi (null, null), PiSZ).[30] People are to be under optimal pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic treatment and show evidence of progressive lung disease (e.g. lower forced expiratory volume per second (FEV1) predicted, impaired walking capacity or increased number of exacerbations) as evaluated by a healthcare professional experienced in the treatment of alpha1-proteinase inhibitor deficiency.[30]

The most common side effects include dizziness, headache, dyspnoea (shortness of breath) and nausea.[30] Allergic reactions have been observed during treatment, some of which were severe.[30]

Aerosolized-augmented A1AT therapy is under study.[when?] This involves inhaling purified human A1AT into the lungs and trapping the A1AT into the lower respiratory tract. However, inhaled A1AT may not reach the elastin fibers in the lung where elastase injury occurs. Further study is currently underway.[33] Recombinant alpha-1 antitrypsin is not yet available for use as a medication but is under development.[34]

History

[edit]Axelsson and Laurell first investigated the possibility of allelic variants of A1AT leading to disease in 1965.[35]

See also

[edit]- Alpha 1-antichymotrypsin, another serpin that is analogous for protecting the body from excessive effects of its own inflammatory proteases

- Orosomucoid is a related alpha 1 protein

References

[edit]- ^ a b c ENSG00000277377 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000197249, ENSG00000277377 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000071177 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Gettins PG (December 2002). "Serpin structure, mechanism, and function". Chemical Reviews. 102 (12): 4751–804. doi:10.1021/cr010170. PMID 12475206.

- ^ Guttman O, Baranovski BM, Schuster R, Kaner Z, Freixo-Lima GS, Bahar N, et al. (February 2015). "Acute-phase protein α1-anti-trypsin: diverting injurious innate and adaptive immune responses from non-authentic threats". Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 179 (2): 161–172. doi:10.1111/cei.12476. PMC 4298394. PMID 25351931.

- ^ Winkler IG, Hendy J, Coughlin P, Horvath A, Lévesque JP (April 2005). "Serine protease inhibitors serpina1 and serpina3 are down-regulated in bone marrow during hematopoietic progenitor mobilization". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 201 (7): 1077–88. doi:10.1084/jem.20042299. PMC 2213124. PMID 15795238.

- ^ Richler R, Forssmann W, Henschler R (June 2017). "Current developments in mobilization of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and their interaction with niches in bone marrow". Transfus Med Hemother. 44 (3): 151–164. doi:10.1159/000477262. PMC 5473067. PMID 28626366.

- ^ "NM_001127701.1(SERPINA1):c.1096G>A (p.Glu366Lys)". ClinVar Genomic variation as it relates to human health. U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Insittues of Health. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

Interpretation: Pathogenic risk factor

- ^ a b Kolarich D, Weber A, Turecek PL, Schwarz HP, Altmann F (June 2006). "Comprehensive glyco-proteomic analysis of human alpha1-antitrypsin and its charge isoforms". Proteomics. 6 (11): 3369–80. doi:10.1002/pmic.200500751. PMID 16622833. S2CID 25498702.

- ^ Lapidot T, Petit I (September 2012). "Current understanding of stem cell mobilization: the roles of chemokines, proteolytic enzymes, adhesion molecules, cytokines, and stromal cells". Exp Hematol. 30 (9): 973–981. doi:10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00883-4. PMID 12225788.

- ^ DeMeo DL, Silverman EK (March 2004). "Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency. 2: genetic aspects of alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency: phenotypes and genetic modifiers of emphysema risk". Thorax. 59 (3): 259–64. doi:10.1136/thx.2003.006502. PMC 1746953. PMID 14985567.

- ^ Taggart C, Cervantes-Laurean D, Kim G, McElvaney NG, Wehr N, Moss J, et al. (September 2000). "Oxidation of either methionine 351 or methionine 358 in alpha 1-antitrypsin causes loss of anti-neutrophil elastase activity". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (35): 27258–65. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004850200. PMID 10867014.

- ^ Owen MC, Brennan SO, Lewis JH, Carrell RW (September 1983). "Mutation of antitrypsin to antithrombin. alpha 1-antitrypsin Pittsburgh (358 Met leads to Arg), a fatal bleeding disorder". The New England Journal of Medicine. 309 (12): 694–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM198309223091203. PMID 6604220.

- ^ Verheul MK, Yee A, Seaman A, Janssen GM, van Veelen PA, Drijfhout JW, et al. (June 2017). "Identification of carbamylated alpha 1 anti-trypsin (A1AT) as an antigenic target of anti-CarP antibodies in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". Journal of Autoimmunity. 80: 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2017.02.008. PMID 28291659.

- ^ Mackiewicz A, Kushner I, Baumann H, eds. (1993). "Acute phase response: an overview". Acute phase proteins: molecular biology, biochemistry, and clinical applications. CRC Press. pp. 3–19. ISBN 1-000-14197-7. OCLC 1164833220.

- ^ "Alpha-1-Proteinase Inhibitor, Human". Drugs.com. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new chemical entities in Australia, 2016". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines and biologicals: TGA annual summary 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Regulatory Decision Summary for Pronextica Liquid". Drug and Health Products Portal. 14 November 2023. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Respreeza - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 10 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Aralast NP". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Aralast". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Glassia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Prolastin". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Prolastin-C". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 September 2017. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Zemaira". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Respreeza EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Alkins SA, O'Malley P (March 2000). "Should health-care systems pay for replacement therapy in patients with alpha(1)-antitrypsin deficiency? A critical review and cost-effectiveness analysis". Chest. 117 (3): 875–80. doi:10.1378/chest.117.3.875. PMID 10713018.

- ^ Brantly ML, Lascano JE, Shahmohammadi A (November 2018). "Intravenous Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Therapy for Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency: The Current State of the Evidence". Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases. 6 (1): 100–114. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.6.1.2017.0185. PMC 6373587. PMID 30775428.

- ^ Usmani OS (July 2020). "Feasibility of Aerosolized Alpha-1 Antitrypsin as a Therapeutic Option". Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 7 (3): 272–9. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.7.3.2019.0179. PMC 7857706. PMID 32726075.

- ^ Bianchera A, Alomari E, Michielon A, Bazzoli G, Ronda N, Pighini G, et al. (December 2022). "Recombinant Alpha-1 Antitrypsin as Dry Powder for Pulmonary Administration: A Formulative Proof of Concept". Pharmaceutics. 14 (12): 2754. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14122754. PMC 9784676. PMID 36559248.

- ^ Axelsson U, Laurell CB (November 1965). "Hereditary variants of serum alpha-1-antitrypsin". American Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 466–72. PMC 1932630. PMID 4158556.[citation needed]

Further reading

[edit]- Kalsheker N (April 1989). "Alpha 1-antitrypsin: structure, function and molecular biology of the gene". Bioscience Reports. 9 (2): 129–38. doi:10.1007/BF01115992. PMID 2669992. S2CID 34243822.

- Crystal RG (December 1989). "The alpha 1-antitrypsin gene and its deficiency states". Trends in Genetics. 5 (12): 411–7. doi:10.1016/0168-9525(89)90200-X. PMID 2696185.

- Carrell RW, Jeppsson JO, Laurell CB, Brennan SO, Owen MC, Vaughan L, et al. (July 1982). "Structure and variation of human alpha 1-antitrypsin". Nature. 298 (5872): 329–34. Bibcode:1982Natur.298..329C. doi:10.1038/298329a0. PMID 7045697. S2CID 11904305.

- Elliott PR, Abrahams JP, Lomas DA (January 1998). "Wild-type alpha 1-antitrypsin is in the canonical inhibitory conformation". Journal of Molecular Biology. 275 (3): 419–25. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1458. PMID 9466920.

- Miyamoto Y, Akaike T, Maeda H (March 2000). "S-nitrosylated human alpha(1)-protease inhibitor". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 1477 (1–2): 90–7. doi:10.1016/S0167-4838(99)00264-2. PMID 10708851.

- Coakley RJ, Taggart C, O'Neill S, McElvaney NG (January 2001). "Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: biological answers to clinical questions". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 321 (1): 33–41. doi:10.1097/00000441-200101000-00006. PMID 11202478. S2CID 2458903.

- Lomas DA, Lourbakos A, Cumming SA, Belorgey D (April 2002). "Hypersensitive mousetraps, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency and dementia". Biochemical Society Transactions. 30 (2): 89–92. doi:10.1042/BST0300089. PMID 12023831.

- Kalsheker N, Morley S, Morgan K (April 2002). "Gene regulation of the serine proteinase inhibitors alpha1-antitrypsin and alpha1-antichymotrypsin". Biochemical Society Transactions. 30 (2): 93–8. doi:10.1042/BST0300093. PMID 12023832.

- Perlmutter DH (December 2002). "Liver injury in alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: an aggregated protein induces mitochondrial injury". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 110 (11): 1579–83. doi:10.1172/JCI16787. PMC 151639. PMID 12464659.

- Lomas DA, Mahadeva R (December 2002). "Alpha1-antitrypsin polymerization and the serpinopathies: pathobiology and prospects for therapy". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 110 (11): 1585–90. doi:10.1172/JCI16782. PMC 151637. PMID 12464660.

- Lisowska-Myjak B (February 2005). "AAT as a diagnostic tool". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 352 (1–2): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2004.03.012. PMID 15653097.

- Lomas DA (2005). "Molecular mousetraps, alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency and the serpinopathies". Clinical Medicine. 5 (3): 249–57. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.5-3-249. PMC 4952210. PMID 16011217.

- Rudnick DA, Perlmutter DH (September 2005). "Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: a new paradigm for hepatocellular carcinoma in genetic liver disease". Hepatology. 42 (3): 514–21. doi:10.1002/hep.20815. PMID 16044402. S2CID 37875821.

External links

[edit]- The MEROPS online database for peptidases and their inhibitors: I04.001 Archived 1 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Proteopedia: Alpha-1-antitrypsin

- Human SERPINA1 genome location and SERPINA1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.