Alligator (film)

| Alligator | |

|---|---|

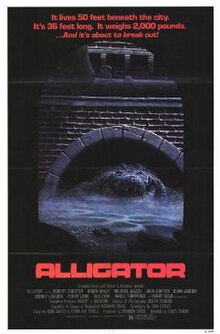

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Lewis Teague |

| Screenplay by | John Sayles |

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Brandon Chase |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Joseph Mangine |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Craig Hundley |

Production company | Group 1 Films[1] |

| Distributed by | Group 1 Films[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 94 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[2] |

| Box office | $6,459,000 |

Alligator is a 1980 American independent horror film directed by Lewis Teague and written by John Sayles. It stars Robert Forster, Robin Riker and Michael V. Gazzo. It also includes an appearance by actress Sue Lyon in her last screen role. Set in Chicago, the film follows a police officer and a reptile expert who track an enormous, ravenous man-eating alligator flushed down the toilet years earlier, that is attacking residents after escaping from the city's sewers.

A direct-to-video sequel was released in 1991, entitled Alligator II: The Mutation. Despite the title, Alligator II shared no characters or actors with the original.[3] A tabletop game based on Alligator was distributed by the Ideal Toy Company in 1980.[4][5]

Plot

[edit]In 1968, a teenage girl purchases a baby American alligator while on vacation with her family at a tourist trap in Florida and gives it the name Ramon. When the family returns home to Chicago, the girl's surly, animal-phobic father promptly flushes it down the toilet and into the city's sewers.

The baby alligator survives by feeding on the discarded carcasses of animals used in illegal experimentation and dumped into the sewers. These animals had been used as test subjects for an experimental growth formula intended to increase agricultural livestock meat production. However, the project was abandoned because while the formula had the desired effect of making the animals larger than normal, it had the unwanted side effect of massively increasing the animals' metabolism, causing them to develop an insatiable appetite. During the 12 years spanning 1968 and 1980, the baby alligator bioaccumulates concentrated amounts of this formula from feeding on these carcasses, causing it to mutate and grow into a perpetually ravenous 36 foot (11 m) monster resembling a Deinosuchus-Purussaurus hybrid with an almost-impenetrable hide.

The alligator begins ambushing and devouring sewer workers. The resulting discovery of body parts exiting the sewers draws in world-weary police detective David Madison who, after a horribly botched case in St. Louis, has gained a reputation for being lethally unlucky for his assigned partners. As David works on the case, his boss Chief Clark introduces him to herpetologist Marisa Kendall. Kendall was in fact the teenager who bought the baby alligator in 1968. The two of them edge into a prickly romantic relationship, and during a visit to Kendall’s house, Madison bonds with her motor-mouthed mother, Madeline.

Madison's reputation as a partner-killer is confirmed when the alligator devours a young officer named Kelly who accompanies Madison into the sewer searching for clues. No one believes Madison’s story due to a lack of a body, and partly because of Slade, the influential local tycoon who sponsored the illegal experiments and therefore wants the truth concealed. This changes when obnoxious tabloid reporter Thomas Kemp, one of the banes of Madison’s existence, goes snooping in the sewers and procures graphic and indisputable photographic evidence of the beast at the involuntary cost of his life. The story quickly garners public attention, and a citywide hunt for the monster is called for.

An attempt by the police to flush out the alligator proves unsuccessful, forcing the alligator to escape from the sewers and come to the surface, where it first kills a police officer and later a young boy who, during a party, is tossed into a swimming pool in which the alligator sought rest. When Madison makes the connection between the alligator and the illegal growth formula experiments, Slade uses his influence with the mayor to get Madison suspended from the force.

The ensuing hunt continues, including the hiring of pompous big-game hunter Colonel Brock to track the animal. Once again, the effort fails: Brock is devoured, the police trip over each other confusedly, and the alligator goes on a rampage through a high-society wedding party hosted at Slade's mansion; among its victims are Slade himself, the mayor, and Slade's chief scientist for the hormone experiments and intended son-in-law. Madison and Kendall finally lure the reptile back into the sewers before setting off explosives, killing it. As they walk away, a drainpipe into the sewer spits out another baby alligator, thus potentially repeating the cycle all over again.

Cast

[edit]- Robert Forster as Detective David Madison

- Robin Riker as Dr. Marisa Kendall

- Leslie Brown as young Marisa

- Michael V. Gazzo as Chief Clark (credited as Michael Gazzo)

- Dean Jagger as Slade

- Sydney Lassick as Luke Gutchel (credited as Sidney Lassick)

- Jack Carter as Mayor Ladue

- Perry Lang as Officer Jim Kelly

- Henry Silva as Colonel Brock

- Bart Braverman as Thomas Kemp

- Angel Tompkins as Newswoman

- Sue Lyon as NBC Newswoman

- Royce D. Applegate as Callan

- Jim Boeke as Shamsky

- Patti Jerome as Madeline Kendall

- Peter Miller as Sergeant Rice

- Pat Petersen as Joey

- Micole Mercurio as Joey's Mother (credited as Micol)

- Dick Richards as Alligator Vendor 2

- Kendall Carly Browne as Ann

- Mike Mazurki as Gatekeeper (credited as Michael Mazurki)

- Kane Hodder as Ramón the Alligator hunter (uncredited)[6]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]The film was first announced by producer Brandon Chase in 1976.[7] Chase was inspired by the urban legend of alligators living in sewers, in particular an account of alligators being found in New York City. In 1977 he announced the film would be set in Wisconsin and made for $1.8 million in Georgia, of which $100,000 was allocated for the alligator. Chase had enjoyed success with The Giant Spider Invasion. "Audiences today are looking for something different," he said. "Huge things coming from outer space or popping up from sewers are different."[8]

Chase signed Lewis Teague to direct. Teague later recalled:

We built a thirty-six-foot alligator out of rubber with an aluminum frame that was articulated so the legs could move, and two very strong men with powerful legs who had to carry that weight got inside. One man had his legs in the front, the other in the rear, and they would walk. This wasn’t my idea; I had been very skeptical about it because I had heard about all the problems Steven Spielberg had with his giant rubber shark when he had made Jaws. I knew the history of that film, and they only used the rubber shark in a few shots. For the most part, he had to create scary scenes from a certain point of view. So I had my doubts about this rubber alligator, but the producer had already started spending money to build it before I got hired to direct the film.[9]

Teague had just made Lady in Red from a script by John Sayles. Teague disliked the script for Alligator and persuaded Chase to hire Sayles to rewrite it.[10] Sayles said "it wasn't a good script... The alligator lived in a sewer for the whole movie. It never got above ground."[11]

Sayles said the original draft had the alligator grow from drinking from a bewery. "It never made sense why it was a giant alligator," he said. "They killed this alligator at an old abandoned sawmill. Someone had left the power on at the old abandoned sawmill. And someone had left a chainsaw lying around the old abandoned sawmill. They plugged the chainsaw in and threw it into the alligator's mouth. All the alligator's thrashing around didn't even pull the plug out, even as the chainsaw cut him to bits."[12] Sayles rewrote the whole script on a cross country flight from New York to Los Angeles.[13]

Sayles said, "My original idea was that the alligator eats its way through the whole socioeconomic system. It comes out of the sewer in the ghetto, then goes to a middle-class neighborhood, then out to the suburbs, and then to a real kind of high-rent area. That's still sort of there on screen, but they couldn't shoot so many scenes — which makes the alligator move so fast, that you don't get the progression."”[14]

Sayles said Robert Forster had input to his character. "He was having a hair problem and Lewis said, “I don’t know, I don’t think it looks that bad,” and Forster said, “What if I start working it in?” And I gave him a few lines about it. It gives the actors something to do apart from “Look!” “Watch out!” and “Duck!”"[15]

Teague later said he wanted to make the film "scary, but I sort of changed course right before we started shooting." This happened because when he tested the alligator "everybody burst into laughter. I thought, ‘This is a comedy; this isn’t going to be a scary film.’ So we’d better tell a funny story. John Sayles wrote a very witty script with a lot of funny lines. That was effective. I did try to put in a few very scary scenes, but they turned out to be not that very scary."[9]

Filming

[edit]Location shooting took place in and around Los Angeles, including in various service tunnels beneath the city streets.[10] In order to create the illusion of the giant alligator, a full scale model was created by Ben Stansbury along with more elaborate head and tail sections for specific action sequences.[10] The internal mechanics used to bring the Alligator to life were created by Richard Helmer who had previous worked on the shark in Jaws.[10] Real alligators were also photographed on miniature sets or integrated with optical enlargement or mattes.[10]

Sayles said "there was a lot of good stuff I wrote that never got shot, whole subplots, because this alligator couldn't cut it. This alligator couldn't do the things they said it could. It couldn't go in the water, for instance."[16]

Commentary on the Lions Gate Entertainment DVD gives the location as Chicago, the police vehicles in the film appear to have Missouri license plates. When the young Marisa returns home with her family from their vacation in Florida, they pass a sign that reads "Welcome to Missouri". Later, the voice of a newscaster identifies Marisa as "a native of our city", implying the location is a city in Missouri other than St. Louis.[17] Also the movie states multiple times it takes place in a city in Missouri other than St. Louis.

Bryan Cranston worked as a special-effects assistant on this film, in charge of making and rigging "the alligator guts" for the film's finale.[18]

Sayles said the film "isn't particularly scary... That alligator wasn't a very mobile creature. It was kind of like being afraid of a Sherman tank. Some of the stuff in the sewer is pretty well done and suspenseful, but only when the alligator eats the cop at the beginning is Alligator scary. That's because of the dangling feet."[19]

Reception

[edit]Critical

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, it holds an 87% approval rating based on 30 reviews, with an average of 6.8/10.[20] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 62 out of 100 based on 10 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[21]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times gave the film a mostly positive review, writing that its "suspense is frequently as genuine as its wit and its fond awareness of the clichés [it uses]".[22] The staff of Variety concluded: "Dumb as it is, director Lewis Teague brings some plusses to the pic. Robert Forster, as a detective, and Riker are amiable leads, never taking the film too seriously. Tech credits are cheap but serviceable."[23] Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film one out of four stars, suggesting that it would be best to "flush this movie down the toilet to see if it also grows into something big and fearsome."[24]

In 2000, Kim Newman of Empire praised the perceived wit of the film's script, as well as the "solid performances, effective effects", and "spirited B-level direction".[25] In 2007, Entertainment Weekly's Chris Nashawaty called the film "Clever, funny, and wonderfully bloody," and wrote that "[this] B movie deserves an... 'A-'".[26] In 2013, Jim Knipfel of Den of Geek awarded the film four-and-a-half out of five stars, calling it "intelligent and stylish".[27] Film historian Leonard Maltin gave the film a score of three out of four stars, and wrote: "If you've got to make a film about a giant alligator that's terrorizing Chicago, this is the way to do it—with a sense of fun to balance the expected violence and genuine scares."[28]

Box office

[edit]The film did not perform particularly strongly at the box office in the USA and Canada but was a large hit in other territories. ABC paid $3 million for the film rights.[2]

Legacy

[edit]Alligator, along with films such as Grizzly (1976), Orca (1977) and Piranha (1978), is sometimes seen as made to capitalize on the success of the film Jaws (1975), whose main antagonist is a man-eating great white shark. John Sayles, who wrote the script for Alligator, also created the screenplay for Piranha two years earlier.[27]

In an interview, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino said that Robert Forster's character, David Madison, inspired the character Max Cherry (also played by Forster) of his 1997 film Jackie Brown.[citation needed]

Sequel

[edit]Home media

[edit]On September 18, 2007, Lions Gate Entertainment released the film on DVD for the first time in the United States. The disc features a new 16x9 anamorphic widescreen transfer in the original 1.78:1 ratio and a new Dolby Digital 5.1-channel sound mix in addition to the original mono mix. The included extras are a commentary track with director Lewis Teague and star Robert Forster, a featurette titled Alligator Author in which screenwriter John Sayles discusses the differences between his original story and the final screenplay, and the original theatrical trailer.

The film had previously been available on DVD in other territories, including a version released in the United Kingdom in February 2003 by Anchor Bay Entertainment. This release features an optional DTS sound mix, includes the sequel Alligator II: The Mutation (1991) on a second disc, and includes the same Teague-Forster commentary found on the recent Lions Gate U.S. release. The Shout! Factory released a collectors edition of Alligator in the two-disc 4K Ultra HD and Blu-Ray set on February 22, 2022 under their Scream! Factory label.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Alligator at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- ^ a b "Sword and Sorcerer producer Brandon Chase sold on fantasy". The Californian. 23 April 1982. p. 19.

- ^ Wingrove, David (1985). Science Fiction Film Source Book. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 0-582-89310-0.

- ^ "Alligator Game (1980)". boardgamegeek.com

- ^ "Alligator Game (1980) Found - ebay Purchaseof the Year" Archived 2013-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. blog.mondotees.com

- ^ Oster, Jimmy (May 9, 2016). "Where in the Horror are they Now? Kane "Jason Voorhees" Hodder!". JoBlo.com. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ "The quote 'em pole". West Bank Guide. 28 July 1976. p. 39.

- ^ "More terror coming up". The Los Angeles Times. 10 January 1977. p. 57.

- ^ a b "Lewis Teague: "The job of a director on the set to a large degree is to keep everybody's morale up"". Film Talk. 22 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Eisenberg, Adam (1980). "Alligator". Cinefantastique. Fourth Castle Micromedia. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Sayles, John; Carson, Diane (1999). John Sayles : interviews. p. 10.

- ^ Sayles & Carson p 61

- ^ Sayles & Carson p 61

- ^ Sayles & Carson p 10

- ^ Sayles, John (1998). Sayles on Sayles. p. 39.

- ^ Sayles & Carson p 61

- ^ Mcgue, Kevin (April 23, 2010). "Alligator Film Review". A Life at the Movies. Archived from the original on August 7, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Cranston, Bryan (2016-10-11). A Life in Parts. Simon and Schuster. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-4767-9385-6.

- ^ Sayles & Carson p 62

- ^ "Alligator". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ "Alligator Reviews". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 5, 1981). "The Screen: 'Alligator': Long in the Tooth". The New York Times. No. C12, Section 3, Page 12, Column 3. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ "Alligator". Variety. December 31, 1979. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 26, 1980). "Alligator". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- ^ Newman, Kim (January 1, 2000). "Alligator Review". Empire. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ Nashawaty, Chris (October 1, 2007). "Alligator". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Knipfel, Jim (June 21, 2013). "Alligator (1980): Lookback and Review". Den of Geek. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2017). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide: The Modern Era, Previously Published as Leonard Maltin's 2015 Movie Guide. Plume. p. 26. ISBN 978-0525536192.

External links

[edit]- Alligator at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Alligator at IMDb

- Alligator at Rotten Tomatoes

- Alligator at AllMovie

- 1980 films

- 1980 horror films

- 1980 independent films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s monster movies

- 1980s science fiction horror films

- American exploitation films

- American independent films

- American monster movies

- American natural horror films

- American science fiction horror films

- Films about crocodilians

- Films based on urban legends

- Films directed by Lewis Teague

- Films set in Chicago

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Films with screenplays by John Sayles

- Giant monster films

- Films about mutants

- American police detective films

- Films about scientists

- Films about animal testing

- English-language independent films

- 1980 science fiction films

- Films set in Illinois

- English-language science fiction horror films