Alberht of East Anglia

| Alberht | |

|---|---|

| King of the East Angles | |

| Reign | 749 – about 760, jointly with Beonna and possibly Hun |

| Predecessor | Ælfwald |

| Successor | Æthelred I |

Alberht (also Ethælbert or Albert; ruled 749 – about 760) was an eighth-century ruler of the kingdom of East Anglia. He shared the kingdom with Beonna and possibly Hun, who may not have existed. He may still have been king in around 760. He is recorded by the Fitzwilliam Museum and the historian Simon Keynes as Æthelberht I.[1]

Historians have accepted that Alberht was a real historical figure who was possibly an heir of Ælfwald. At Ælfwald's death in 749, the kingdom was divided between Alberht and Beonna, who was perhaps a Mercian and who took the lead in issuing regnal coinage and maintaining a military alliance with Æthelbald, king of Mercia. Alberht was ruling in East Anglia when Æthelbald was murdered in 757, after which Beornred ruled for a year in Mercia, before Offa seized power from him. The evidence of Alberht's single discovered coin indicates that he had sufficient authority to issue his own coinage, a degree of independence that was soon eclipsed by the rapid growth of Offa's power in East Anglia.

Background

[edit]

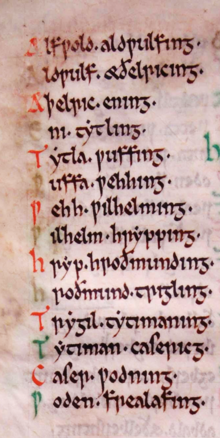

Alberht of East Anglia became king of the East Angles after his predecessor Ælfwald died in 749, after ruling for thirty-six years.[2] During Ælfwald's rule, East Anglia enjoyed sustained growth and stability, albeit under the senior authority of the Mercian king Æthelbald,[3] who ruled his kingdom from 716 until he was murdered by his own men in 757.[4] Ælfwald was the last of the Wuffingas dynasty, who had ruled East Anglia since the sixth century.[5] The East Anglian pedigree in the Anglian collection, which was probably compiled in 725 or 726 during the reign of Ælfwald, lists the royal line of East Anglia, from Ælfwald to the Germanic god Woden.[6][7]

Joint rule with Beonna

[edit]Alberht is so obscure that for many centuries he was known only from a single statement in a late compilation of material. A reference derived from tradition can be found in the annal for 749 in the Historia Regum, a mediaeval work possibly produced in part by Byrhtferth of Ramsey. In the annal, it is stated that "Hunbeanna and Alberht divided the kingdom of the East Angles between themselves".[8] Until the 1980s, this record stood alone and unverifiable, with the exception of a single coin attributed to Beonna and two other brief mentions of him. Since then, well over a hundred coins attributed to Beonna have been found,[9] many in archaeologically secure contexts,[10] so that it is now clear that a ruler named Beonna did rule in East Anglia at that time, as originally suggested in 1905 by the English historian H. M. Chadwick.[11][12] The historian Steven Plunkett has suggested that the Hun- element in the annal was at some time joined with the -beanna element in error by a scribe.[8] Marion Archibald, a numismatist at the British Museum for 33 years, and the historian Dorothy Whitelock both asserted that the term Hunbeanna could be split into two separate names, Hun and Beonna.[13][14][15] Archibald acknowledges that nothing at all is known of Hun, noting that the name may a hypocorism for a person with a name beginning in hun- or ending in -hun,[16] whilst Whitelock partitions the kingdom of the East Angles between Alberht, Hun and Beonna.[15]

Scholars have since realized that these exceedingly sparse references were accurate, and that East Anglia was indeed ruled jointly after 749. As a result, Alberht has become a more substantial reality. The identity of these two rulers (or possibly three, if Hun is included) and the reason for this division of power remain unknown. The historian Barbara Yorke suggests the possibility that the kings each ruled a separate part of the kingdom at this time, but acknowledges that the political landscape of 749 is not well understood.[17] D. P. Kirby gives an alternative view of the events that may have occurred following the death of Ælfwald. He connects Alberht with Æthelberht II of East Anglia and states that Alberht was still ruling in 794, which would imply that he reigned for around forty-five years.[18]

Beonna is not a typical East Anglian Wuffingas name,[19] but might be connected with the Mercian ruling family, as several members had names starting with a B.[20] Alberht however alliterates suitably with several Wuffingas names:[21] according to Plunkett, it could be accepted as a form of the name Æthelberht, implying that when Ælfwald died, Alberht continued the dynastic line,[8]

Plunkett notes that the large number of coins bearing his name show that Beona was in primary control of the minting of East Anglia's coinage and was at times in a position to consolidate his authority as king.[22] The East Anglians under Beonna co-operated with Æthelbald's Mercians in the Battle of Burford Bridge against Cuthred of Wessex in 752,[23] and, according to Archibald, Beonna can be identified with Beornred, who for a few months ruled Mercia after Æthelbald's assassination in 757.[24]

Coinage

[edit]![a coin of Alberht I.[25] Both sides of the coin have text in runes laid out between the limbs of a saltire pommée, decorated with pellets. Obverse: eþ æl be rt; reverse: ti æl re d.[26]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/24/%C3%86thelberht_I_Eastanglian_coin.jpg/220px-%C3%86thelberht_I_Eastanglian_coin.jpg)

According to the numismatists Philip Grierson and Mark Blackburn, the minting of coins in East Anglia probably began during the reign of Beonna. A mint probably operated from Suffolk: coins continued to be produced through a period of Mercian hegemony and East Anglian independence, until the invasion by the Vikings in the second half of the ninth century.[27]

The confirmation of Alberht as a historical figure emerges from the discovery by controlled excavation of a single coin, considered to be unique, that can be attributed to him.[28]

The authenticity and date-horizon of the coin is not in doubt: it was discovered by Valerie Fenwick at Burrow Hill, at Butley, Suffolk, in a stratified deposit which also contained several varieties of late sceattas of a runic type and coins that were minted by Beonna. It was found in a defensible estuary island site in a strategic position near Rendlesham, a known seat of Wuffingas power.[29] The site is located 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) due east of Sutton Hoo.[30]

The clear and carefully formed runes on the sceatta[14] reveal the moneyer's name—'Tiælred'—which is perhaps a version of Coeldred: the obverse reads 'Ethælbert'.[31] Of about 42% silver,[32] the coin is closely connected to Beonna,[14] being struck on a module comparable to the larger planchet which characterises the later strikes of Beonna's most prolific moneyer, Efe. The formula resembles the money made for Beonna by Wilred, but the confident lettering and beading more resembles the work of Efe.[33] Its resemblance to the coins made for Beonna "strongly suggests" to Archibald that it was made for a king who ruled in East Anglia at around the same time.[14]

The coin formed part of a presentation to the British Museum in 1992, to mark the society's twenty-fifth anniversary of the British Museum Society.[28]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Keynes 2014, p. 530.

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Archibald 1985, p. 23.

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 112.

- ^ Fryde et al. 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Dumville 1976, p. 40, note 2.

- ^ Dumville 1976, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Plunkett 2005, p. 155.

- ^ Page 2006, p. 274.

- ^ Archibald 1985, p. 10.

- ^ Archibald 1985, p. 33.

- ^ Chadwick 1905, p. 412.

- ^ Archibald 1985, p. 39.

- ^ a b c d Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 9.

- ^ a b Whitelock 1979, p. 264.

- ^ Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Kirby 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Yorke 2002, p. 119.

- ^ Yorke 2002, pp. 3, 68.

- ^ Plunkett 2005, pp. 155, 158.

- ^ Plunkett 2005, p. 159.

- ^ Archibald 1985, pp. 33–34.

- ^ "Full Record of 1995.6002: coin of Alberht". The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Archived from the original on 22 February 2019. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Grierson & Blackburn 1986, p. 588.

- ^ a b Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Plunkett 2005, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Page 1973, p. 126.

- ^ Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, p. 11.

- ^ Archibald, Cowell & Fenwick 1996, pp. 10–11.

Sources

[edit]- Archibald, Marion M. (1985). "The Coinage of Beonna in the light of the Middle Harling Hoard" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 55: 10–54.

- Archibald, Marion M.; Cowell, M.R.; Fenwick, V.H. (1996). "A sceat of Ethelbert I of East Anglia and recent finds of coins of Beonna" (PDF). British Numismatic Journal. 65: 1–19.

- Chadwick, Hector Munro (1905). Studies on Anglo-Saxon Institutions. Cambridge: University Press. OCLC 60735181.

- Dumville, David N. (1976). "The Anglian collection of royal genealogies and regnal lists". Anglo-Saxon England. 5. Cambridge University Press: 23–50. doi:10.1017/S0263675100000764. JSTOR 44510666. S2CID 162877617. (registration required)

- Fryde, E. B.; Greenway, D. E.; Porter, S.; Roy, I. (1986). Handbook of British Chronology (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56350-X.

- Grierson, Philip; Blackburn, Mark (1986). Mediaeval European Coinage I: The Early Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-03177-6.

- Keynes, Simon (2014). "Appendix I: Rulers of the English, c. 450–1066". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England (Second ed.). Chichester, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 521–538. ISBN 978-0-470-65632-7.

- Kirby, D. P. (2000). The Earliest English Kings. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-4152-4211-8.

- Page, Raymond Ian (1973). An Introduction to English Runes. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-946 X.

- Page, R. I. (2006). "Anglo-Saxon Runes: some statistical problems". In Holmberg, B.; Nielsen, M. L.; Stoklund, M. (eds.). Runes and their Secrets: Studies in Runology. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculalum Press. ISBN 87-635-0428-6.

- Plunkett, Steven (2005). Suffolk in Anglo-Saxon Times. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3139-0.

- Whitelock, Dorothy, ed. (1979). English Historical Documents, 500-1042 (2nd ed.). London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14366-7.

- Yorke, Barbara (2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16639-X.

Further reading

[edit]- J. Campbell (Ed.), The Anglo-Saxons (Oxford 1982).

- Fenwick, V.H. (1984). "Insula de Burgh: Excavations at Burrow Hill, Butley, Suffolk 1978-1981". Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History. 3: 35–54.

- J. A. Giles, Roger of Wendover's Flowers of History (Translation - 2 Vols.) (London 1849).