Kusaila

| Kusaila Ibn Malzam | |

|---|---|

| King of Altava | |

| |

| King of Altava | |

| Reign | ? - 688 |

| Predecessor | Sekerdid |

| Leader of the Berber | |

| In office | c. 680s - 688 |

| Successor | Kahina |

| Died | 688 AD Valley of Mamma, east of Timgad in the Aurès Mountains |

| Burial | |

| Religion | Arian Christianity |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

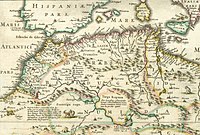

Kusaila ibn Malzam (Arabic: كسيلة بن ملزم,[1][2]) was a 7th-century Berber Christian ruler of the kingdom of Altava and leader of the Awraba tribe, a Christianised sedentary Berber tribe of the Aures and possibly Christian king of the Sanhaja.[3] Under his rule his domain stretched from Volubilis in the west to the Aurès in the east and later Kairouan and the interior of Ifriqiya.[4][5][6][7] Kusaila is mostly known for prosecuting an effective Berber military resistance against the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb in the 680s. He died in one of those battles in 688.

Etymology

[edit]Possibly from Caesilius (Cecilian), a Roman name widely used among Christianized Berbers, but more likely from Berber (Aksil) "Feline", still attested in the dialects of Aurès, region of which Kusila was native.[8][better source needed]

Historical importance

[edit]Initially the Berber States were able to defeat the Umayyad invaders at the Battle of Vescera (modern Biskra in Algeria), that was fought in 682 AD between the Berbers of King Kusaila and their Byzantine allies from the Exarchate of Africa against an Umayyad army under Uqba ibn Nafi, the founder of Kairouan.[9]

Uqba ibn Nafi had led his men in an invasion across North Africa, eventually reaching the Atlantic Ocean and marching as far south as the Draa and Sous rivers. On his return, he was met by the Berber-Byzantine coalition at Tahuda south of Vescera, his army was crushed and he himself was killed. As a result of this crushing defeat Kusaila took control of Byzacena and a large part of Ifriqiya, the Arabs lost all of their land in Africa west of Cyrenaica and were expelled from the area of modern Tunisia and eastern Algeria for more than a decade.[10][11][12]

Biography

[edit]His homeland was Tlemcen, now in Algeria, according to Ibn Khaldun. However, this account dates from the 14th century, some 700 years later. Indeed, Kusaila, according to historian Noe Villaverde,[13] was probably a king of Altava. Other sources closer to Kusaila's time (ninth century is the earliest available) associate him only with the Aurès Mountains in Algeria.[2] Kusaila grew up in Berber tribal territory during the time of the Byzantine exarchate.

Kusaila is speculated to be a Christian based on his Roman-sounding name. According to historian Gabriel Camps, his name was a possible translation in Berber of the Latin name "Caecilius", showing that he was from a noble Berber family.[14] His name even intrigued Orientalists; unlike other Berber kings, like his predecessors Masuna, Masties, Mastigas and Garmul, Arab chroniclers likely transmitted us a name of another language: Latin Caecilius, a common name found in the graves of Volubilis.

He was captured by Uqba but in AD 683 he succeeded in escaping and raised against his tormentors a large force of Christian Berber and Byzantine soldiers. And attacked Uqba, killing him near Biskra. After Uqba's death his armies retreated from Kairouan, which Kusaila took as his capital, and for a while he seems to have been at least in name the master of all North Africa. But his respite from battle was to be short-lived. Five years later Kusaila was killed in battle against fresh Arab forces led by a Muslim general from Damascus. This soldier was himself ambushed and put to death by Byzantine sea-raiders shortly afterwards. For a while confusion reigned, but the Awraba recognized the weakness of their position and eventually capitulated to the newly re-organized and reinforced Arab army. With the death of Kusaila, the torch of resistance passed to a tribe known as the Jerawa, who had their home in the Aurès.

According to late Muslim accounts (11th century through to ibn Khaldun in the 14th century) the amir of the Muslim invaders, who was then a freed slave called Abu al-Muhajir Dinar, surprisingly invited Kusaila to meet with him in his camp. Abu al-Muhajir Dinar convinced him to accept Islam and join his army with a promise of full equality with the Arabs (678). Abu al-Muhajir was a master in diplomacy and thoroughly impressed Kusaila with not only his piety but with his high sense of respect and etiquette. Kusaila incorporated the Awraba-Sanhaja into the conquering Arab force and participated in their uniformly successful campaigns under Abu al-Muhajir.

This amir was then forcibly replaced by Uqba ibn Nafi, who treated Kusaila and his men with contempt. Eventually Uqba's disrespect enraged Kusaila and provoked a plot of revenge. On the army's return from Morocco, Uqba allowed his troops to break up and go home. The remainder, about 300, were vulnerable and exhausted. On the return march to Kairouan, Kusaila joined with the Byzantine forces and organised an ambush. The Christian-Berber force, about 5000 strong, defeated the Arabs and felled Uqba at Tahudha near Biskra in 683. Kusaila now held undisputed mastery over North Africa and marched to Kairouan in triumph.[10]

The above account is disputed by some historians, who prefer the earlier 9th-century sources.[2][15] According to these, Abu al-Muhajir had no connection with Kusaila, nor did Uqba ibn Nafi until he was ambushed at Tahudha. These earlier sources also describe Kusaila as a Christian, not a Muslim convert. They do agree, however, that he led a Berber force when he defeated Uqba.

In 687 AD Arab reinforcements arrived under Zuhayr ibn Qays. Kusaila met them in 688 AD at the Battle of Mamma. Vastly outnumbered, the Awraba were defeated and Kusaila was killed. In 693, Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan sent an army of 40,000 men commanded by Hassan ibn al-Nu'man to Cyrenaica and Tripolitania in order to remove the Byzantine threat to the Umayyads in North Africa. They met no rival groups until they reached Tunisia where they captured Carthage and defeated the Byzantines and Imazighen around Bizerte.[16] However, it was not the last instance of Berber resistance, since Kahina succeeded Kusaila as the war leader of the Berber tribes in the 680s.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dictionary of African Biography, Volumes 1-6, By Emmanuel Kwaku Akyeampong, Henry Louis Gates

- ^ a b c Modéran, Y. (2005). "Kusayla, l'Afrique et les Arabes". Identités et Cultures dans l'Algérie Antique. University of Rouen. ISBN 2-87775-391-3.

- ^ Midstream Archived 2024-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 39 Theodor Herzl Foundation

- ^ The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live InHugh Kennedy Archived 2023-03-26 at the Wayback Machine Hachette UK,

- ^ Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places Archived 2024-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Trudy Ring, Noelle Watson, Paul Schellinger Routledge

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Tunisia Archived 2023-03-26 at the Wayback Machine Kenneth J. Perkins Rowman & Littlefield

- ^ Islam, 01 AH-250 AH: A Chronology of Events Archived 2023-04-03 at the Wayback Machine Abu Tariq Hijazi Message Publications,

- ^ Hadadou, Mohand Akli (2003). RECUEIL DE PRENOMS BERBERES (in French). Alger: Haut commissariat à l'amazighité. p. 102.

- ^ McKenna, Amy (2011). The History of Northern Africa. Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-1615303182. Archived from the original on 2024-05-22. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ a b Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman : conquest and identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439-700. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0521196970.

- ^ Cambridge Medieval History, Shorter: Volume 1, The Later Roman Empire to the Twelfth Century Archived 2024-05-22 at the Wayback Machine C. W. Previté-Orton CUP Archive,

- ^ Histoire de la Tunisie: De Carthage à nos jours Archived 2024-05-22 at the Wayback Machine By Sophie Bessis

- ^ Noé Villaverde, Vega. El Reino mauretoromano de Altava, siglo VI [The Mauro-Roman kingdom of Altava]. p. 355.

- ^ Camps, Gabriel (1984). "Rex gentium Maurorum et Romanorum. Recherches sur les royaumes de Maurétanie des VIe et VIIe siècles". Antiquités africaines (in French). 20 (1): 183–218. doi:10.3406/antaf.1984.1105. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2014-05-04.

- ^ Benabbès, A. (2005). "Les premiers raids arabes en Numidie Byzantine: questions toponymiques". Identités et Cultures dans l'Algérie Antique. University of Rouen. ISBN 2-87775-391-3.

- ^ Islamic books by ibn Taymiyyah, Maqdisi and Abdullah Azzam. Ibn Taymiyyah and Sayyid Qutb. 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Hrbek, I. (ed.). General History of Africa III: Africa From the Seventh to the Eleventh Century.