Air China Flight 112

Electron micrograph of SARS virion[1] | |

| Incident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 15 March 2003 |

| Summary | Largest in-flight super-spread transmission of SARS during the 2003 epidemic |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 737-36N |

| Operator | Air China |

| Registration | B-5035[2] |

| Flight origin | Hong Kong International Airport |

| Destination | Beijing Capital International Airport |

| Occupants | 120 |

| Passengers | 112 |

| Crew | 8 |

| Fatalities | 5 |

| Survivors | 115 |

Air China Flight 112 was a scheduled international passenger flight on 15 March 2003 that carried a 72-year-old man infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). This man would later become the index passenger for the infection of another 20 passengers and two aircraft crew, resulting in the dissemination of SARS north to inner Mongolia and south to Thailand. The incident demonstrated how a single person could spread disease via air travel and was one of a number of superspreading events in the global spread of SARS in 2003. The speed of air travel and the multidirectional routes taken by affected passengers accelerated the spread of SARS with a consequential response from the World Health Organization (WHO), the aviation industry and the public.[3][4][5]

The incident was atypical, in that passengers sitting at a distance from the index passenger were affected and the flight was only three hours long. Until this event, it was thought that there was only a significant risk of infection in flights of more than eight hours duration and in just the two adjacent seating rows. Other flights at the time with confirmed passengers with SARS did not have the same extent of infection spread.[3]

Some experts have questioned the interpretation of the incident and highlighted that some passengers may have been infected already. The role of cabin air has also come under question and the incident involving Flight 112 has led to some experts calling for further research into patterns of airborne transmission on commercial flights.[6]

Background

[edit]

The 2003 SARS epidemic was caused by the then newly emerging subtype of coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which was previously unknown in humans.[7] It was first noted in Guangdong, China in November 2002. Three months later, it surfaced in Hong Kong, Vietnam, Singapore, and Canada. Transmission was primarily through inhalation of droplets from a human cough or sneeze and people affected presented with a fever greater than 38 °C (100 °F) and dry cough, typically appearing as atypical pneumonia.[8]

By 28 February 2003, the SARS epidemic had reached Hanoi and was considered of global concern, causing the WHO headquarters in Geneva to issue a global health alert on 12 March 2003, the first since the 1994 India Plague epidemic.[9] Led by the WHO, management of the event consisted predominantly of contact tracing, isolating the affected person and quarantining their contacts.[7] The last known case of human-to-human transmission of SARS was in 2004.[10][11]

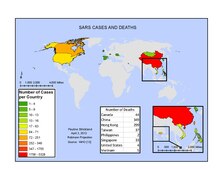

Of the more than 8,000 people that were reported to develop SARS between November 2002 and July 2003 worldwide, more than half were from mainland China (particularly Beijing), 20% were healthcare workers and 29 countries reported 774 deaths. Although the overall fatality rate was 15%, it rose to 55% in those over 60.[7][12]

Passengers

[edit]

On 15 March 2003, Air China Flight 112, a Boeing 737-300, flew from Hong Kong on a three-hour flight to Beijing carrying 120 people including 112 passengers, 6 flight attendants and 2 pilots.[13] The flight had 88% occupancy.[3]

The index passenger was a 72-year-old man, LSK, who had been in Hong Kong since 26 December 2002.[14] Later, he had been visiting his sick brother at the Prince of Wales Hospital between 4 March and 9 March 2003, when his brother died. During this time there were known cases of SARS on the same ward and LSK's niece, who had been visiting her sick father, also developed SARS.[3] On 13 March 2003, two days prior to embarking on Flight 112, LSK developed a fever.[3] He then consulted a doctor the next day, one day before taking the flight.[14] He was unwell when boarding the flight and sat in seat 14E.[4] With six people per row, LSK had 23 passengers sitting in front, or in the same row, and 88 passengers sitting behind him.[3]

One Taiwanese engineering firm had seven employees on the flight. On 21 March 2003, they returned to Taipei.[14] In addition, there was a group of 33 tourists and an official from the Chinese ministry of commerce.[3]

Pattern of spread

[edit]LSK became the source of infection to another 20 passengers and two crew members.[3] Passengers up to seven rows away from him were affected.[4] Of those later interviewed, eight of the 23 in front or to the side and 10 of the 88 behind LSK, caught the virus.[3] The incident became the largest in-flight transmission of SARS, probably due to the presence of a super-spreader.[15]

Upon arrival at Beijing, LSK was seen in hospital but not admitted.[16] The following day he was taken by family members to a second hospital, where he was successfully resuscitated before being admitted with suspected atypical pneumonia.[16] He subsequently died on 20 March 2003.[16] Following investigations, at least 59 people with SARS in Beijing were traced back to LSK, including three of his own family and six of the seven healthcare workers from the emergency room during his resuscitation.[16]

Within eight days of the flight, 65 passengers were contacted, of which 18 had become unwell. Sixteen of these were confirmed with SARS and the other two were highly probable. Thirteen were from Hong Kong, four from Taiwan and one from Singapore. Another four from China who were not directly interviewed, were reported to the WHO. The average time for the onset of symptoms was four days. None of these 22 people had any other exposure to SARS other than on Flight 112.[3]

Flight attendant Meng Chungyun, age 27, travelled home to Inner Mongolia where she infected her mother, father, brother, doctor and husband Li Ling, who later died.[2] Flight attendant Fan Jingling also travelled back home to Inner Mongolia and together both became sources of infection for almost 300 people in Inner Mongolia.[4]

The group of 33 tourists who were on the flight destined for a five-day tour of Beijing, were joined by another three people in Beijing.[3] Two of the three were together and the third unconnected. The three and the group were unknown to each other and had different plans before and after the flight. On 23 March 2003, a local hospital notified the Department of Health in Hong Kong of three people with SARS. Contact tracing revealed that these three people were the same three that had joined the Beijing tourist group, 10 of whom also became unwell. Laboratory testing confirmed SARS in all 13.[3]

One passenger was an official from the Chinese ministry of commerce. He fell ill in Bangkok. On 23 March 2003, he returned to Beijing, sitting next to Pekka Aro, a Finnish official at the International Labour Organization in Geneva, who was going to Beijing in preparation for a China employment forum. Aro became ill on 28 March and was admitted to hospital on 2 April. He was the first foreign national to die from SARS in China.[4] Five of the passengers from Flight 112 died from SARS.[6]

Interpretation

[edit]WHO investigations of cases of SARS on 35 other flights, revealed that transmission occurred in only four other passengers.[7] One other flight that carried four people with SARS, transmitted it to only one other passenger.[3] In the first five months that SARS spread rapidly, 27 people had been infected on a number of flights, of which a disproportionate 22 were on Air China Flight 112,[4] representing the largest in-flight transmission of SARS.[15]

The Flight 112 incident was one of the several superspreading events that contributed to the dissemination of the SARS virus in 2003. Other super-spreaders, defined as those that transmit SARS to at least eight other people, included the incidents at the Hotel Metropole in Hong Kong, the Amoy Gardens apartment complex in Hong Kong and one in an acute care hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[17]

WHO officials had acknowledged that air travellers "within two rows of an infected person could be in danger".[8] However, the virus had also been found to survive for days in the environment, giving rise to the possibility of spread by contact with surfaces including armrests and tray tables.[8]

The whole incident was atypical. Infection typically spreads at the destination but is rarely spread on flight. The air in the cabin is cleaned using high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, in a similar way as cleaning the air in an operating theatre. The greatest risk is sitting next to or in the couple of rows in front or behind the index passenger.[4][8]

Medical advisor to the International Air Transport Association, Claude Thibeault, however, felt that the incident had been misinterpreted, saying: "people automatically assume there was transmission" and "we cannot prove there was transmission on this plane. They could have already been infected when they got on board".[6]

Response

[edit]During the height of the global epidemic, the occupancy of hotels in Hong Kong dropped to less than 5%, with a couple of the grandest hotels completely empty.[9]

The Lancet reported that "SARS exemplifies the ever-present threat of new infectious diseases and the real potential for rapid spread made possible by the volume and speed of air travel." The same report also endorsed further research into patterns of airborne transmission on commercial flights.[6][18]

Concerns from aircrew led to the Association of Flight Attendants in the United States to petition the Federal Aviation Administration to issue an emergency order requiring airlines to offer gloves and surgical masks to airline attendants, or at least allow them to bring their own.[8]

The effort to control the spread of SARS varied from country to country. Singapore adopted infra-red scanners, Taiwan introduced mandatory quarantine and in Toronto, health notification cards were endorsed. A global standard was subsequently developed by the WHO.[19]

The financial cost to the Asia-Pacific region only was estimated to be US$40 billion.[19]

Some experts have criticised the restriction of air traffic and closing of national borders during outbreaks, stating that this can lead to difficulties in supplying medical aid to affected areas and closing borders may also deter healthcare workers. In addition, in Michael T. Osterholm's 2017 book the Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs, he says "you have to screen many, many people to find anybody with an infectious disease". Infra-red scanners may not detect disease in its incubation period and fever may be a sign of many other diseases.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ "SARS | SARS-CoV Photos and Images | CoV Disease | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 8 February 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- ^ a b 毕耀华; 武二秀; 石动花 (2003). "两名空中女乘务员患SARS的应对措施和流行病学分析". 中华航空航天医学杂志 (in Chinese). 14 (2). Chinese Medical Association: 69–71. ISSN 1001-6589.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Olsen, Sonja J.; Chang, Hsiao-Ling; Cheung, Terence Yung-Yan; Tang, Antony Fai-Yu; Fisk, Tamara L.; Ooi, Steven Peng-Lim; Kuo, Hung-Wei; Jiang, Donald Dah-Shyong; Chen, Kow-Tong (18 December 2003). "Transmission of the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome on Aircraft". New England Journal of Medicine. 349 (25): 2416–2422. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa031349. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 14681507.

- ^ a b c d e f g Abraham, Thomas (2004). "4.A Global Emergency". Twenty-first Century Plague: The Story of SARS. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-9622097025.

- ^ "Infectious diseases on aircraft". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 13 June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Johnson, Mark; Oxenden, McKenna (24 November 2017). "Flight Risk". Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Cliff, Andrew; Smallman-Raynor, Matthew (2013). Oxford Textbook of Infectious Disease Control: A Geographical Analysis from Medieval Quarantine to Global Eradication. OUP Oxford. pp. 95–96. ISBN 9780199596614.

- ^ a b c d e Koh, D.; Lim, M. K. (1 August 2003). "SARS and occupational health in the air". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 60 (8): 539–540. doi:10.1136/oem.60.8.539. ISSN 1351-0711. PMC 1740596. PMID 12883012.

- ^ a b Watson, James L. (2006). Kleinman, Arthur (ed.). SARS in China: Prelude to Pandemic?. Stanford University Press. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-0-8047-5314-2.

- ^ "China confirms SARS in deceased woman". CIDRAP. 30 April 2004. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ CDC (3 March 2016). "Disease of the Week - SARS". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Shen, Zhuang (2004). "Superspreading SARS Events, Beijing, 2003 — Volume 10, Number 2—February 2004 — Emerging Infectious Diseases — CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (2): 256–60. doi:10.3201/eid1002.030732. PMC 3322930. PMID 15030693. Archived from the original on 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- ^ Whaley, Floyd (2006). "15. Flight CA112: facing the spectre of in-flight transmission" (PDF). SARS; How a Global Epidemic was Stopped. WHO. pp. 149–154. ISBN 92-9061-213-4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-04-08. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ a b c Benitez, Mary Ann (30 June 2006). "Flight CA112: the spread of a deadly virus". South China Morning Post. South China Morning Post Publishers. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ a b Mangili, Alexandra; Vindenes, Tine; Gendreau, Mark (9 October 2015). "Infectious Risks of Air Travel". Microbiology Spectrum. 3 (5). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.IOL5-0009-2015. ISSN 2165-0497. PMID 26542037.

- ^ a b c d Liang, W. (2004). "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Beijing, 2003". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 10 (1): 25–31. doi:10.3201/eid1001.030553. PMC 3092360. PMID 15078593. Archived from the original on 2018-06-02. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ "Progress in Global Surveillance and Response Capacity 10 Years After Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome". medscape.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2019.(subscription required)

- ^ Mangili A, Gendreau MA (2005). "Transmission of infectious diseases during commercial air travel". Lancet. 365 (9463): 989–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71089-8. PMC 7134995. PMID 15767002.

- ^ a b Bowen, John T.; Laroe, Christian (2006). "Airline Networks and the International Diffusion of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)". The Geographical Journal. 172 (2): 130–144. Bibcode:2006GeogJ.172..130B. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4959.2006.00196.x. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 3873984. PMC 7194177. PMID 32367889.(subscription required)

External links

[edit]- "CDC SARS Response Timeline". www.cdc.gov. 19 July 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.