Adam Forepaugh

Adam Forepaugh | |

|---|---|

Publicity photo of Adam Forepaugh | |

| Born | February 28, 1831 |

| Died | January 22, 1890 (aged 58) |

| Resting place | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Horse trader, Circus owner |

Adam John Forepaugh (born Adam John Forbach;[1] February 28, 1831 – January 22, 1890) was an American horse trader and circus owner. From 1865 through 1890 his circus operated under various names including Forepaugh's Circus, Forepaugh's Gigantic Circus and Menagerie, The Forepaugh Show, 4-PAW Show, The Adam Forepaugh Circus, and Forepaugh & The Wild West.

He ran a successful horse trading business which provided horses to street railway companies. He became wealthy selling horses to the U.S. government during the American Civil War. He entered the circus business by taking part ownership in a circus due to an unpaid debt for the purchase of 44 horses.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Forepaugh and P. T. Barnum had the two largest circuses in the United States and competed fiercely. His innovations included commission of the first railroad cars for a traveling circus in 1877, the first three-ring presentation and the first Wild West show.[1] After Forepaugh's death in 1890, his circus operations were merged with the Sells Brothers Circus to form the Forepaugh-Sells Brothers' Circus in 1900.

Early life and horse trading career

[edit]Forepaugh was born into poverty in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to John A. Forbach, a butcher, and Susannah Heimer. He began working in a butcher shop at age 9, earning $4 a month.[2] He left home on the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad to Cincinnati, where he worked in cattle appraising and managing stagecoach lines. He moved to New York City and formed a livestock and horse trading business. He became the largest purveyor of horses in New York state and earned a reputation as an expert judge of horses.[3]

Forepaugh ran a successful business selling horses to street railway companies. He purchased old "nags" from one streetcar company, allowed the horses to rejuvenate on an island in the Schuylkill River, and then sold the horses at a higher price to a different streetcar company.[4] Forepaugh’s horse selling enterprise during the American Civil War became his most lucrative business venture. The war made horses scarce and therefore very valuable. He became wealthy selling horses to the U.S. government.[3]

Circus career

[edit]Forepaugh entered the circus business in 1864, when he sold 44 horses to John V. "Pogey" O'Brien for $9,000 to use in the Tom King Excelsior Circus. O'Brien could not repay the loan and Forepaugh assumed partial ownership of the circus. The next year, he and O'Brien purchased the Jerry Mabie Menagerie and created two circuses with their combined assets: The Great National Circus and the Dan Rice Circus. Forepaugh sold the Great National Circus and renamed the Dan Rice Circus as his own name. In November of 1865 Forepaugh opened the Philadelphia Circus and Menagerie at 10th and Callowhill Streets. This was the first permanent home of his touring circus show.[5] His circus toured 250 or more days each year and employed over 400 performers and workmen.[6] His annual average profit exceeded $300,000.[7]

Forepaugh was different from most of his fellow circus operators. Already independently wealthy when he entered the circus business, he was much less a showman and much more a businessman—a stark contrast to P. T. Barnum and the Ringling Brothers. He was intimately involved in all aspects of the circus business. He would regularly seat himself at the main entrance into the circus, a vantage point that ensured that his face was seen by all and from which, it was rumored, he could estimate the night's receipts to hold his employees accountable.[8] Through the 1870s and into the 1880s, Forepaugh and P. T. Barnum had the two largest circuses in the nation. Forepaugh had more animals than Barnum and generally paid higher salaries to the much-favored European talent. The two men constantly fought each other over rights to perform in the most-favored venues.[9]

They signed truces in 1882, 1884, and 1887, dividing the country into exclusive territories to avoid disputes.[10] But at least twice, they decided to pool their resources and perform together. In 1880, Forepaugh and Barnum combined their shows for a Philadelphia engagement. In 1887, Forepaugh obtained permission to perform in Madison Square Garden, a venue that Barnum considered to be exclusively his but had forfeited by his neglect to renew his contract.[8] A compromise was negotiated, and once again the two circuses presented a combined performance in the largest circus performance to date.[11]

In 1889, Forepaugh sold his circus acts to James Anthony Bailey and James E. Cooper and sold his railroad cars to the Ringling Brothers.[12] The Ringlings used the equipment to transform their circus from a small animal-powered production to a huge rail-powered behemoth, which later purchased the Barnum & Bailey Circus. Thus, in liquidating his circus assets, he indirectly contributed to the demise of his arch-rival.

In her 1932 biography, Mary Elitch Long—the first woman to own a zoo—commented on purchasing animals from Forepaugh:

"Fine specimens were purchased from Forepaugh's collections and other sources, and a standing order placed with importers of rare and unusual creatures. P.T. Barnum was a frequent visitor during this summer and took a personal pride in this feature."[13]

Business practices

[edit]

The American circus business in this period was known for its unscrupulous business practices—practices of which Forepaugh was a willing participant. Forepaugh was also noted for his business acumen and marketing prowess, which made his circus profitable every year except one.[8]

An example of Forepaugh's unscrupulous methods was his rivalry with Barnum over Barnum's white elephant. Barnum had purchased, at great cost, an ostensibly white elephant, only to discover upon delivery that it was pink, with great spots. Forepaugh heard of this and saw an opportunity to one-up Barnum. He whitewashed a regular gray elephant, called it the "Light of Asia", and marketed it as the real thing.[14] To further illustrate the spirit of the business dealings between the two, a reporter who managed to sneak up and remove some of the whitewash from the "Light of Asia" to prove Forepaugh's fraud was able to sell this information to Barnum, instead of writing a story about it for his newspaper.[15]

Some of Forepaugh's methods were truly innovative, however. He was the first circus operator to separate the menagerie from the big ring in order to attract church goers who might be leery of the "sinful" attractions of circus acts, yet still desirous to see the exotic animals in the menagerie.[16]

Innovations

[edit]Forepaugh was responsible for many innovations in circus history, which influenced circuses for many years.

- He was the first to incorporate a "Wild West Show" into his circus.

- In 1869, he was the first to use two separate "bigtop" tents at the same time, one for the circus performance and the other for the menagerie.

- In search of new talent, he sponsored a $10,000 beauty contest in 1881, looking for the "most beautiful woman in America". The winner was Louise Montague, a 21-year-old New York City actress blessed with a "charming blue eye" and "... magnificent teeth, which she shows to advantage in conversation".[17] Many believe this was the first beauty pageant in America.

- He hired an African-American elephant trainer named Ephraim Thompson in a time when blacks rarely had positions of such stature.

The famous "sucker" quote

[edit]The quote "There's a sucker born every minute, but none of them ever die" is often attributed to P. T. Barnum. The source of the quote is most likely famous con-man Joseph ("Paper Collar" Joe) Bessimer. Forepaugh attributed the quote to Barnum in a newspaper interview in an attempt to discredit him.[18] However, Barnum never denied making the quote. It is said that he thanked Forepaugh for the free publicity he had given him.

Death and legacy

[edit]

Forepaugh died January 20, 1890, in Philadelphia during the 1889–1890 flu pandemic and is buried in the family vault at Laurel Hill Cemetery.[3] Many local charities and churches in the Philadelphia area benefited from his estate, including Temple University, Morris Animal Refuge, St. Agnes, St. Luke's and Children's Medical Center.

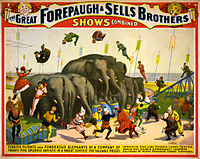

After Forepaugh's death, his circus operations merged with the Sells Brothers Circus to form the Forepaugh-Sells Brothers' Circus in 1900.[19]

An article at the end of 1907 observed that the Ringling brothers intended to close the remains of their property, the former Forepaugh show, eighteen years after its original owner's death, and stop using the name and likeness which had "been seen oftener than that of any other American, dead or alive" by that writer's estimation.[20]

Forepaugh gave his name to Forepaugh Park, the 1890s baseball venue in Philadelphia.

In 2010, a young adult book Tombstone Tea[21] by Joanne Dahme takes place in Laurel Hill Cemetery and Forepaugh is one of the characters in the book.

Posters for Forepaugh & Sells Brothers

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "A Great Showman Dead". Philadelphia Times (via newspapers.com, subscription req'd). 24 January 1890. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Traber, J Milton "Adam Forepaugh's Life" Billboard (Cincinnati, OH) 8, October 1910: 13–24. https://archive.org/stream/billboard22-1910-10#page/n92/mode/1up/.

- ^ a b c "Death Of Adam Forepaugh. The Veteran Showman Falls a Victim to Influenza And Pneumonia". The New York Times. January 24, 1890. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

Adam Forepaugh, the veteran circus manager, died late last night at his residence in this city. He had been ailing for some time past. ...

- ^ Kuntz, Jerry (2010). A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S.F. Cody and Maud Lee. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8061-4149-7. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Running Away With The Circus At 10th And Callowhill". Hidden City Philadelphia. 2016-10-20. Retrieved 2023-11-29.

- ^ Waite, Dave (15 July 2021). "Rewind: July 15, 2021 – "Thrilling Attractions & Weird Wonders"". www.wcnyhs.org. Warren County N.Y. Historical Society. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Leavitt, Michael Bennett (1912). Fifty Years in Theatrical Management. New York: Broadway Publishing Co. p. 125. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Albrecht, Ernest. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press, 2000. s.v. "Forepaugh, Adam." [1] (registration required)

- ^ Slout, William L. (1998). Olympians of the Sawdust Circle. San Bernardino, CA: The Borgo Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0-8095-0310-7. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Apps, Jerry (2005). Ringlingville USA: The Stupendous Story of Seven Siblings and Their Stunning Circus Success. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-87020-354-1. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Wilmeth, Don B and Tice L Miller "Adam Forepaugh" Cambridge Guide to American Theatre (New York: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1996): 158.

- ^ Apps, Jerry (2005). Ringlingville USA: The Stupendous Story of Seven Siblings and Their Stunning Circus Success. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin Historical Society Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-87020-354-1. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Lawrence, Caroline Dier (1932). The lady of the Gardens: Mary Elitch Long. Saturday Night Pub. Co. p. 24. OCLC 21432197.

- ^ Kuntz, Jerry (2010). A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S.F. Cody and Maud Lee. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8061-4149-7. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Wallace, Irving. The Fabulous Showman: The Life and Times of P. T. Barnum. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1959: 297.

- ^ "Forepaugh, Adam". Dictionary of American Biography. Vol. V. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1946. p. 522.

- ^ Police Gazette, April 23, 1881

- ^ Kuntz, Jerry (2010). A Pair of Shootists: The Wild West Story of S.F. Cody and Maud Lee. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8061-4149-7. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Forepaugh-Sells Brothers' Circus". The Hartford Courant. May 9, 1900. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

The combined Adam Forepaugh-Sells Brothers' Circus will be in Hartford next week Tuesday. ...

- ^ "Old Circus Name to Go". York (Pennsylvania) Dispatch (via newspapers.com, sub req'd). 16 December 1907. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- ^ Tombstone Tea Amazon listing Amazon.com. Retrieved 5 October 2009.

External links

[edit]- Advertisement for Adam Forepaugh’s Circus in Athletic Park, Washington, DC, published in The National Republican, April 11, 1885

- Milner Library Illinois State University Digital Collections - Official Route 26th Annual Tour Adam Forepaugh Great All-Feature Show 1889

- New York Public Library Digital Collections - Adam Forepaugh

- 1831 births

- 1890 deaths

- 19th-century American businesspeople

- American butchers

- American circus owners

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- Businesspeople from Philadelphia

- Deaths from the 1889–1890 flu pandemic

- Horse trader

- Infectious disease deaths in Pennsylvania

- Wild West show founders and owners