Act of Consolidation, 1854

This article is missing information about remaining county/city commissioners' duties and whether they were later consolidated into the Philadelphia City Council. (October 2014) |

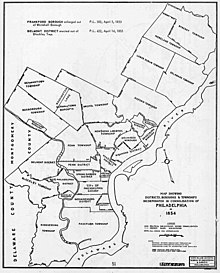

The Act of Consolidation, more formally known as the act of February 2, 1854 (P.L. 21, No. 16), is legislation of the Pennsylvania General Assembly that created the consolidated City and County of Philadelphia, expanding the city's territory to the entirety of Philadelphia County and dissolving the other municipal authorities in the county.

The law was enacted by the General Assembly and approved February 2, 1854, by Governor William Bigler. This act consolidated all remaining townships, districts, and boroughs within the County of Philadelphia, dissolving their governmental structures and bringing all municipal authority within the county under the auspices of the Philadelphia government. Additionally, any unincorporated areas were included in the consolidation. The consolidation was drafted to help combat lawlessness that the many local governments could not handle separately and to bring in much-needed tax revenue for the State.

History

[edit]In early 1854, the city of Philadelphia's boundaries extended east and west between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and north and south between Vine and South streets, representing the present-day Center City section of Philadelphia. The rest of Philadelphia County contained thirteen townships, six boroughs and nine districts. Philadelphia City's recent influx of immigrants spilled over into the rest of Philadelphia County, surging the area's population.[1] In 1840, Philadelphia's population was 93,665 and the rest of the county was 164,372; by 1850 the populations were 121,376 and 287,385 respectively.[2]

One of the major reasons put forth for the consolidation of the city was the county's inability to govern.[3] Law enforcement found it difficult to enforce the peace. A person could break the law in Philadelphia City and quickly cross the border and escape punishment. Districts outside Philadelphia could not control their criminal elements and at the same time refused to let Philadelphia get involved. An example of how poorly law enforcement agencies worked together was in May, 1844 when an anti-Catholic riot erupted in Kensington. The sheriff was the only police officer available in Kensington at the time and when Philadelphia's militia was called they hesitated because they hadn't been reimbursed for past calls. By the time the militia arrived, the riot was out of control. Attempts to improve the issue included an 1845 law that required several of the surrounding districts to maintain adequate law enforcement and an 1850 act that gave Philadelphia law enforcement the authority to police seven surrounding districts.[1] As a result, the act also achieved one of its intended roles: Expand and strengthen the jurisdiction of the Philadelphia Police Department.

The other major reason for consolidation was that Philadelphia's actual population center was not in Philadelphia, but north of Vine Street.

Between 1844 and 1854, Philadelphia's population grew by 29.5 percent. Places like Spring Garden grew by 111.5 percent, and the Kensington section of Philadelphia grew by 109.5 percent. This population shift was draining the city of much-needed tax revenue for police and fire departments, water, sewage, and other city improvements.[4]

Consolidation

[edit]There had been several unsuccessful proposals at consolidation before 1854. The main opposition of consolidation came from the Whig Party. The Whigs usually dominated Philadelphia City elections while the outlying districts were dominated by the Democrats and the Whigs feared they would lose power within the city.[1] With support from all the city's major newspapers, and the end of the Whig party's existence around that time,[5] the consolidation overcame opposition and the issue was brought to the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

Eli Kirk Price brought the issue to the Pennsylvania Senate while Matthias W. Baldwin and William C. Patterson brought it to the House of Representatives. A bill was produced on December 20, 1853, and by January 31, 1854, the bill had passed both houses. The bill was then brought to Governor William Bigler, who was in Erie, Pennsylvania. Bigler was awoken out of bed before midnight on February 2 and signed the bill into law. The signing was rushed because several districts were considering assuming new debts for railroad loans and other projects, with the expectation that the consolidated city would pay instead.[4]

The Act of Consolidation, along with creating Philadelphia's modern border, gave executive power to a mayor who would be elected every two years.[6] The mayor was given substantial control of the police department and control of municipal administration and executive departments with oversight and control of the budget from the city council.[3]

On March 11 there was a large celebration for the consolidation. Governor Bigler, members of the legislature, and chief officers of the state visited the city for the celebration. Events included an excursion on the Delaware River, a ball at the Philadelphia Chinese Museum and a banquet at the Sansom Street Hall the next day.[4]

Although the city and county now shared the same boundaries, a number of city and county functions remained separate. Many of these functions were overseen by "City Commissioners" who were elected separately from the city council and mayor. In 1951, the state constitution was amended to allow cities and counties to fully merge, and Philadelphia voters adopted a new home rule charter that merged nearly all city and county institutions. The new charter took effect in January 1952. Although Philadelphia County has effectively been a legal nullity since then, the county row offices[clarification needed] still exist, though all except the Register of Wills are subject to city civil service rules.[7]

Districts, townships, and boroughs consolidated into Philadelphia

[edit]The following is a list of municipal authorities which were consolidated into the modern City and County of Philadelphia.[8]

- Aramingo Borough

- Belmont District

- Blockley Township

- Bridesburg Borough

- Bristol Township

- Byberry Township

- Delaware Township

- Frankford Borough

- Germantown Borough

- Germantown Township

- Kensington District

- Kingsessing Township

- Lower Dublin Township

- Manayunk Borough

- Moreland Township

- Moyamensing District

- Northern Liberties District

- Northern Liberties Township

- Oxford Township

- Passyunk Township

- Penn District

- Penn Township

- Philadelphia City

- Roxborough Township

- Richmond District

- Southwark District

- Spring Garden District

- West Philadelphia Borough

- Whitehall Borough

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Brookes, Karin; John Gattuso; Lou Harry; Edward Jardim; Donald Kraybill; Susan Lewis; Dave Nelson; Carol Turkington (2005). Zoë Ross (ed.). Insight Guides: Philadelphia and Surroundings (Second Edition (Updated) ed.). APA Publications. p. 359. ISBN 1-58573-026-2.

- ^ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, page 349

- ^ a b Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, page 368

- ^ a b c Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, page 360

- ^ "What Can the Collapse of the Whig Party Tell Us About Today's Politics?".

- ^ Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, page 706

- ^ Heath, Andrew. Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

- ^ "Incorporated District, Boroughs, and Townships in the County of Philadelphia, 1854". Philadelphia History. ushistory.org. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2006.