Bach: The Goldberg Variations (Glenn Gould album)

| Bach: The Goldberg Variations | |

|---|---|

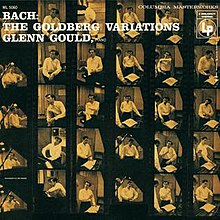

The original Columbia Masterworks album cover shows 30 photos of Gould in the studio, analogous to the 30 variations. | |

| Studio album by | |

| Released | 1956 |

| Recorded | June 10 – June 16, 1955 |

| Genre | Classical |

| Length | 38:34 |

| Label | Columbia |

| External audio | |

|---|---|

on Archive.org |

Bach: The Goldberg Variations is the debut album of Canadian classical pianist Glenn Gould. An interpretation of Johann Sebastian Bach's Goldberg Variations (BWV 988), the 1956 record launched Gould's career as a renowned international pianist, and became one of the most well-known piano recordings.[1] Sales were "astonishing" for a classical album: it was reported to have sold 40,000 copies by 1960, and had sold more than 100,000 by the time of Gould's death in 1982.[2] In 1981, a year before his death, Gould made a new recording of the Goldberg Variations, sales of which exceeded two million by the year 2000.[3]

At the time of the first album's release, Bach's Goldberg Variations—a set of 30 contrapuntal variations beginning and ending with an aria—were outside the standard piano repertoire, having been recorded on the instrument only a few times before, either on small labels or unreleased.[n 1] The work was considered esoteric[4] and technically demanding, requiring awkward hand crossing at times when played on a piano (these passages would be played on two manuals on a harpsichord). Gould's album both established the Goldberg Variations within the contemporary classical repertoire and made him an internationally famous pianist nearly "overnight".[5] First played in concert by Gould in 1954, the composition was a staple of Gould's performances in the years following the recording.

Recording process

[edit]The recordings were made in 1955 at Columbia Records 30th Street studio in Manhattan over four days between June 10 and 16, a few weeks after Gould signed his contract. Columbia Masterworks Records, the company's classical music division, released the album in 1956. Bach: The Goldberg Variations became Columbia's bestselling classical album and earned Gould an international reputation. The record is now in the catalog of Sony Classical Records.

At least one record-company executive questioned Gould's choice of the then-obscure Goldberg Variations for his recorded debut. In a 1981 interview, Gould reflected on the studio's situation: "I think the objections [Columbia] had, which were mild and expressed in a most friendly fashion, were quite logical. I was twenty-two years old and proposed doing my recording debut with the Goldberg Variations, which was supposed to be the private preserve, of, perhaps, Wanda Landowska or someone of that generation and stature. They thought that possibly some more modest undertaking was advisable."[6] Then aged 22, Gould was confident and assertive about his work, and prevailed in the decision as to what he would record for his debut—having also ensured that his contract granted him artistic freedom. Columbia recognized his talent and tolerated his eccentricities; on June 25 the company issued a good-natured press release describing Gould's unique habits and accoutrements. He brought to the studio a special piano chair, bottles of pills, and unseasonable winter clothing; once there, he would soak his hands and arms in very hot water for twenty minutes before playing.[4] Gould often had trouble finding a piano he liked; the Variations were recorded on a Steinway CD 19 piano, a model similar to the piano that Gould himself owned, a CD 174.[7]

The album gained attention for Gould's unique pianistic method, which incorporated a finger technique involving great clarity of articulation (a "detached staccatissimo"), even at great speed, and little sustaining pedal. Gould's piano teacher, Alberto Guerrero, had encouraged Gould to practice "finger tapping", which required very slowly tapping the fingers of the playing hand with the free hand. According to Guerrero, tapping taught the pianist an economy of muscle movement that would enable precision at high speeds. Gould "tapped" each Goldberg variation before recording it, which took about 32 hours.[8]

The extreme tempi of the 1955 performance made for a short record, as did Gould's decision not to play many of the repeats (each variation consists of two parts, traditionally played in an A–A–B–B format). The length of a performance of the Goldberg Variations can therefore vary drastically: Gould's 1955 recording is 38 minutes 34 seconds long, while his reconsidered, slower 1981 version (see below) is 51:18. By way of contrast, fellow Canadian Angela Hewitt's 1999 record is 78:32.[9]

The opportunity to perfect one's work in the studio—what Gould called "take-twoness"—attracted him to the recording studio from the beginning, and separated him from a classical-music tradition which emphasized continuous live performance, even on record. He recorded at least 21 versions of the introductory aria before being satisfied.[10] Over the course of his career, Gould became more and more interested in the creative possibilities of the studio.

Gould wrote the liner notes to the recording. Concluding his back-cover essay on the Goldberg Variations, he wrote: "It is, in short, music which observes neither end nor beginning, music with neither real climax nor real resolution, music which, like Baudelaire's lovers, 'rests lightly on the wings of the unchecked wind.' It has, then, unity through intuitive perception, unity born of craft and scrutiny, mellowed by mastery achieved, and revealed to us here, as so rarely in art, in the vision of subconscious design exulting upon a pinnacle of potency."

The 1955 recording was added to the US National Recording Registry in 2003.[11]

Reappraisal

[edit]Gould commented in a 1959 interview with Alan Rich that he had begun to study the Goldberg Variations in about 1950, around the age of 17. It was one of the first works that he had learned "entirely without [his] teacher", and which he had "made up [his] mind about relatively [early]". He noted that his performance view of the Variations now involved slowing the piece down: "[That] is about the only musical change that has gone on, but it implies, I think, possibly an approach of slightly greater breadth now than at that time... I was very much in a 'let's get the show on the road and get through with it' sort of mood [during the recording]. I felt that to linger unduly over anything would be to take away from a sort of overall unity of things... In part it was brought about by a reaction against so much piano playing which I had heard and, in fact, part of the way in which I myself was taught, which was in the school of the Romantic pianists of the Cortot/Schnabel tradition".[12]

Gould later became more critical of his 1955 interpretation, expressing reservations about its fast tempi and pianistic affectation. He found much of it "just too fast for comfort",[13] and lamented the 25th variation, which sounded "like a Chopin nocturne"—to Gould, an undesirable quality, given his aversion to much of the Romantic repertoire. He continued, "I can no longer recognize the person who did that. To me today that piece has intensity without any sort of false glamour. Not a pianistic or instrumental intensity, a spiritual intensity."[14]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks composed by Johann Sebastian Bach.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Variations Nos. 1 Through 16" | 16:25 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Variations Nos. 17 through 30" | 22:05 |

1981: a new recording

[edit]| Bach: The Goldberg Variations | |

|---|---|

| Studio album by | |

| Released | 1982 |

| Recorded | 1981 |

| Genre | Classical |

| Label | CBS Masterworks |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[16] |

Shortly before his death in 1982, Gould re-recorded the Goldberg Variations digitally and in stereo in the Columbia 30th Street Studio in New York City; it was the last album to be recorded in that studio before it closed. He largely abandoned the showmanship of the 1955 performance, choosing instead a more introspective interpretation with more calculated phrasing and ornamentation. For the 1981 version, Gould sought to unify the variations by finding proportional rhythmic relationships between them. While the 1955 recording ignores all repeats, Gould now played 13 of the first repeats, while still declining to play the repeats of the B sections, which he felt undermined the sense of closure of each variation as it modulated back to the tonic (G major or minor). He repeated the A section of the nine canons, and the four strict four-part variations (4, 10, 22, and 30). Kevin Bazzana suggests that Gould wanted to "set apart consistently and audibly those variations in which formal counterpoint is of primary importance".[17]

Arriving within a year of his death, the 1981 recording is popularly recognized as "autumnal", a symbolic testament to Gould's career.[18] The album won two awards in 1983: the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Soloist Performance, and in Canada, the Juno Award for Classical Album.[19]

Re-releases

[edit]Both albums have been repackaged on numerous occasions since their original releases. For example, in 2002, Sony Classical issued a three-CD collection titled A State of Wonder: The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 & 1981.[1] It includes both Goldberg recordings (the latter remastered from analogue tapes), and a third disc with 1955 studio outtakes and an interview with Gould documentarian and music critic Tim Page. The same label released The Goldberg Variations: The Complete Unreleased Recording Sessions in 2017, comprising seven discs of outtakes and related material from the 1955 recording session. In 2022, a ten-disc set of the 1981 album's recording sessions was released.[20]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ First by Claudio Arrau and Eunice Norton, both in 1942; later by Rosalyn Tureck and Jörg Demus; Arrau's recording for RCA was only publicly released in 1988. Source: Goldberg Discography by Performer).

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Fleming, Colin (November 28, 2003). "Reissues: Glenn Gould – 'A State of Wonder: The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 & 1981' [review]". Goldmine. 29 (24): 63. This article may be found online as Fleming, Colin (July 12, 2004). "A State of Wonder: The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 & 1981". All About Jazz: Beyond Jazz.

- ^ Bazzana (2003, p. 153)

- ^ Stegemann, Michael, "Bach for the 21st century", introduction to Glenn Gould, The Complete Bach Collection, p. 5, Sony Classical

- ^ a b Bazzana (2003, pp. 150 – , 151)

- ^ Siepmann, Jeremy (January 1990). "Glenn Gould and the Interpreter's Prerogative". The Musical Times. 131 (1763). The Musical Times, Vol. 131, No. 1763: 25–27. doi:10.2307/965621. JSTOR 965621.

- ^ Gould (1999, p. 342) "Interview 8"

- ^ "Glenn Gould From A to Z". Archived from the original on February 19, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Bazzana (2003, p. 73)

- ^ Kingwell 2009, pp. 199–200

- ^ Kingwell, book jacket. See chapter 21, "Takes".

- ^ "Goldberg Variations" (PDF). National Recording Preservation Board. Retrieved April 8, 2021.

- ^ Gould (1999, p. 135) "Interview 3"

- ^ Bazzana (2003, p. 453)

- ^ Gould (1999, p. 332) "Interview 7"

- ^ Sanderson, Blair. "Glenn Gould Bach: The Goldberg Variations". AllMusic. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ Colter Walls, Seth (March 26, 2017). "Glenn Gould: Bach: The Goldberg Variations". Pitchfork. Retrieved March 26, 2017.

- ^ Bazzana, Kevin (1997). Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work: A Study in Performance Practice. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 95. ISBN 0198166567.

- ^ Bazzana (2003, p. 455)

- ^ "The JUNO Awards". Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ "Sony Classical Releases The Goldberg Variations: The Complete 1981 Studio Sessions – Glenn Gould Foundation". www.glenngould.ca. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bazzana, Kevin (2003). Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-1101-6. OCLC 52286240.

- Gould, Glenn (1999). Roberts, John Peter Lee (ed.). The Art of Glenn Gould: Reflections of a Musical Genius. Toronto: Malcolm Lester Books. ISBN 978-1-894121-28-6. OCLC 45283402.

- Kingwell, Mark (2009). Glenn Gould. Extraordinary Canadians. Toronto: Penguin Canada. ISBN 978-0-670-06850-0. OCLC 460273223.