A Preface to Paradise Lost

First edition | |

| Author | C.S. Lewis |

|---|---|

| Language | English language |

| Genre | Preface, Literary criticism |

| Publisher | Oxford University Press |

Publication date | 1942 |

| Publication place | England |

A Preface to Paradise Lost is one of C. S. Lewis's most famous scholarly works.[1] The book had its genesis in Lewis's Ballard Matthews Lectures,[2] which he delivered at the University College of North Wales in 1941.[2] It discusses the epic poem Paradise Lost, by John Milton.[3]

Lewis's work responds to Denis Saurat's work Milton: Man and Thinker, which had celebrated "Milton the man, as well as the centrality of the 'personal' (Milton's heresies), to an understanding of the epic".[4] Lewis disagrees with this point of view:

Lewis dismisses what he calls Milton's "private thoughts," "idiosyncratic and accidental as they are," as well as the "heresies" that "reduce themselves to something very small". Lewis's Paradise Lost rather is defined as "Augustinian and Hierarchical," and also, as he writes with a slight nudge and a wink, "Catholic" (although he does immediately acknowledge that he's using the term, in its ordinary sense, to mean "universal," not "Roman Catholic").[4]

Summary

[edit]The book has no material before Chapter 1 besides a dedication to Charles Williams.[3]

Epic genre and criticism

[edit]Chapter 1, "Epic Poetry", introduces the epic genre.[3]

Chapter 2, "Is Criticism Possible?", is a digression that replies to a remark by T.S. Eliot in "A Note on the Verse of John Milton". Eliot had said:

There is a large class of persons, including some who appear in print as critics, who regard any censure upon a 'great' poet as a breach of the peace, as an act of wanton iconoclasm, or even hoodlumism. The kind of derogatory criticism that I have to make upon Milton is not intended for such persons, who cannot understand that it is more important, in some vital respects, to be a good poet than to be a great poet; and of what I have to say I consider that the only jury of judgement is that of the ablest poetical practitioners of my own time.[5]

Lewis paraphrases the last clause and focuses on it, but interprets it rather as a representative of the idea "that poets are the only judges of poetry", meant in a general sense, rather than applying only to Eliot's specific criticism of Milton at that specific time.[3] Lewis then critically examines this idea, believing that it leads to a situation where every poet would be trapped in a self-referential cycle, where their own judgment of being a poet is a necessary precondition for their critique to be valuable.

Chapters 3–5 are titled "Primary Epic", "The Technique of Primary Epic", and "The Subject of Primary Epic". They discuss Lewis's concept of "primary epic", the oldest kind of epic genre, represented by the epics of Homer and by Beowulf.

Chapter 6, "Virgil and the Subject of Secondary Epic", discusses the influence of Virgil's Aeneid on the secondary epic genre, which came after primary epic, primarily by introducing the idea that it should have a "great theme".[3] It also introduces the importance of vocation, and the choice between vocation and happiness, as a typical trait of secondary epic.[6]

Style

[edit]

Chapter 7, "The Style of Secondary Epic", explains the peculiar style of Virgil and Milton as coming from the fact that epic is no longer recited but can only be read, and must give the effect of the performance entirely through the writing.

Lewis points out three main mechanisms through which Milton achieves his elevated style, namely the use of archaic and unfamiliar constructs, the use of proper names, and the constant allusion to sensory experiences.[3]

Similes

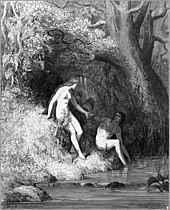

[edit]Lewis explains Milton's unique approach to similes. Unlike traditional similes that draw clear analogies, Milton's similes often have superficial logical connections but profound emotional or thematic resonances. The "Miltonic simile" thus operates on two levels: a surface-level logical connection and a deeper, emotional or thematic linkage. This technique is shown by when "Paradise is compared to the field of Enna", with the primary connection being how both locations are "one beautiful landscape to another (IV, 268)". Beneath this surface connection, "the deeper value of the simile lies in the resemblance which is not explicitly noted as a resemblance at all, the fact that in both these places the young and the beautiful while gathering flowers was ravished by a dark power risen up from the underworld."[3][7]

This simile neglects that Eve "is far more responsible for her own fall than was Proserpina and when expelled she will bring death and pain down upon herself, her spouse, and all their descendants to a degree that would seem to exceed Ceres's (Demeter's) terrible pain at Hades's abduction of her daughter", as Stephen Scully points out.[7] Lewis himself notes that sometimes, the logical underpinning of Milton's similes can stretch thin, as in the case of Satan's association with the unpleasant smell of fish.[3]

Description versus arousal

[edit]

Focusing on Satan's approach to Paradise in book IV, lines 131–286, Lewis analyses how Milton's style does not describe events and landscapes in the narrative, but rather, "while seeming to describe", uses general language to arouse "the Paradisal idea" as it exists "in our own depth".[3] Lewis "justly"[8] observes that this is done by making the sequence of Satan's entering Paradise resemble a dream:[8] as Satan approaches Paradise, Milton describes various tiers of the landscape, but just when it seems like we've reached the highest point, another layer or aspect is revealed, and "as in dream landscapes, we find that what seemed the top is not the top".[3] Lewis perceptively observed that "we experience an almost kinesthetic sense of straining to look higher and higher so as to take in the full view."[9]

Chapter 8, "Defence of this Style", defends the style of secondary epic against some objections.[3]

Worldview

[edit]Chapter 9, "The Doctrine of the Unchanging Human Heart", criticizes the idea that readers should seek an "unchanging human heart" beneath all the theology of Milton, or, more generally, to "read past" the outmoded ideas of premodern literature.[3]

Chapter 10, "Milton and St. Augustine", gives context to the poem by presenting a "version of the Fall story" based on St. Augustine, since Lewis claims that Milton's version of the story is substantially the same as the one given by Augustine, "which is that of the Church as a whole".[3] Lewis says that he hopes "that this short analysis will prevent the reader from ever raising certain questions";[3] this sentence was seized upon by Michael Bryson as a sign that Lewis wished to downplay Milton's heresies in such a way as to make it impossible for his readers to even think to question Milton's orthodoxy.[10]

Chapter 11, "Hierarchy", explains the effect of the idea of hierarchy as it applies to the poem. Paradise Lost manifests, according to Lewis, "order, proportion, measure, and control".[4][3] Lewis, commenting on critical views in which "there is felt to be a disquieting contrast between republicanism for the earth and royalism for Heaven", argues that "all such opinions are false and argue a deep misunderstanding of Milton's central thought".[6][3] Arguing from the principle that "the goodness, happiness, and dignity of every being consists in obeying its natural superior and ruling its natural inferiors",[11][3] Lewis claims that there is no contradiction between Milton's poem and his politics, because Milton believed that God was his "natural superior" and that Charles Stuart was not.[11] According to Matthew Jordan, Lewis is correct[6] in asserting that, in holding this position, Milton "belongs to the ancient orthodox tradition of European ethics",[3] but Lewis "downplays the significance of Milton using this tradition against kings rather than to bolster their position by affirming that society, and above all the king, embody such relations of natural superiority."[6]

Chapter 12, "The Theology of Paradise Lost", evaluates to what extent the poem shows that its author is a heretic. Lewis claims that "as far as doctrine goes, the poem is overwhelmingly Christian. Except for a few isolated passages it is not even specifically Protestant or Puritan. It gives the great central tradition."[3][12] Paradise Lost, according to Lewis, bases its poetry on conceptions not to be found in seventeenth-century radical politics, but in those that have been held "always and everywhere by all".[3][4]

According to Lewis, criticism should not be interested at all in connections to "Milton's private thinking". "In Paradise Lost we are to study what the poet, with his singing robes about him, has given," and not the "private theological whimsies"[13][3] that he "laid aside" during "his working hours as an epic poet":[3][4]

Lewis's Milton hearkens back to the attempts of Bentley and Johnson to separate the private radical, heterodox, and "wild" man from the putatively orthodox achievement of the poem. To the extent that Lewis attacks, like Eliot, "personality," he is attacking a Milton attached to "revolutionary politics, antinomian ethics, and the worship of Man by Man," but also a conception of criticism that focuses more on "psychology" than on the "best of Milton which is in his epic" (129, 90). "Why," he writes, with a jibe at Saurat's emphasis on passion and sensuality, "must Noah always figure in our minds drunk and naked, never building the Ark?" (90). Saurat, through his reading of the romantics, had brought not only the individual but the "unconscious" into Paradise Lost (184); Lewis, the figure of Anglican orthodoxy, for whom "Decorum" is the "grand masterpiece," prefers Milton the "very disciplined artist" to the admittedly "undisciplined man" of passion (90).[4]

Satan and other angels

[edit]

Chapter 13, "Satan", defends the idea that Milton did not seek to present Satan as an admirable figure,[3] but rather, that Milton "uses all his skill to make us regard Satan as a despicable human being".[12] Lewis focuses on Satan's egoism, claiming that "Satan's monomaniac concern with himself and his supposed rights and wrongs is a necessity of the Satanic predicament".[3][12]

Lewis urges that we should "simply reject everything" Satan "says as untrue, even from his own point of view",[14] and refers to him as "a personified self-contradiction".[3][15] Lewis demonstrates, "with perhaps more vigor than necessary", that Satan's line, "Evil be thou my Good", is absurd.[8] Lewis comments that, by his argument in book V, lines 856ff, Satan "renders himself ridiculous", since he "both loses in dignity and produces just the evidence to prove that he was not self-created".[8] Helen Gardner says that "C.S. Lewis, building, as he delighted to own, on Mr. Williams, destroyed, one hopes for ever, the notion that Satan had grounds for his rebellion."[12]

"From hero to general, from general to politician, from politician to secret service agent, and thence to a thing that peers in at bedroom or bathroom windows, and thence to a toad, and finally to a snake—such is the progress of Satan",[3] according to Lewis's analysis of Milton.[3] Lewis rightly[12] rejects "the belief that Milton began by making Satan more glorious than he intended and then, too late, attempted to rectify the error", saying that "such an unerring picture of 'the sense of injured merit' in its actual operations upon character cannot have come about by blundering and accident."[3][12]

Chapter 14, "Satan's Followers", discusses the infernal debate among the fallen angels in Hell in Book II of Paradise Lost.[3]

Chapter 15, "The Mistake about Milton's Angels", explains that Milton probably believed in a kind of "Platonic Theology" according to which angels were not incorporeal, but instead had bodies made of very fine and subtle matter.

Humanity

[edit]

Chapter 16, "Adam and Eve", explains the portrayal of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost as wise and mature, rather than "innocent" in the sense of "childish".[3]

Chapter 17, "Unfallen Sexuality", discusses whether Milton succeeded in his portrayal of human sexuality in its unfallen state. Lewis displays "disquiet at Milton's attributing sexual modesty to Eve and allowing her to blush", and "uneasiness at Milton's making it quite clear that there was pleasure in the act of love before the Fall";[12] these attitudes were not shared by Helen Gardner.[12] Lewis suggests that Milton should instead have "treated the loves of Adam and Eve as remotely and mysteriously as the loves of the angels",[3] and Helen Gardner disagreed with this as well.[12]

Chapter 18, "The Fall", claims that "Eve fell through Pride", whereas "Adam fell by uxoriousness".[3] It claims that the precise "name in English" for the sin committed by Eve is "Murder";[3] this analysis was criticized by Helen Gardner, although she agreed with Lewis's claim that the temptation and fall of Eve is not dramatically exploited, or lingered on:[12] as Lewis says, "the whole thing is so quick, each new element of folly, malice, and corruption enters so unobtrusively, so naturally, that it is hard to realize we have been watching the genesis of murder."[3][12]

Conclusion

[edit]Chapter 19, "Conclusion", gives "a very short estimate of the poem's value as a whole".[3] He famously describes the last two books as an "untransmuted lump of futurity", and "inartistic".[14][3] He remarks on other critics, claiming that "after Blake, Milton criticism is lost in misunderstanding, and the true line is hardly found again until Mr. Charles Williams's preface."[4][3]

Reception

[edit]Helen Gardner describes A Preface to Paradise Lost as "immensely influential".[12] Michael Bryson, in The Atheist Milton, mentions the influence of A Preface to Paradise Lost on views of Milton's theological outlook, by saying that "it has been primarily since the 1942 publication of C.S. Lewis's A Preface to Paradise Lost that the image of Milton as the great defender of a somehow Augustinian orthodoxy has taken hold."[10] Bryson highlights "the continuing effect of Lewis's work" on such views.[10]

William Kolbrener claims that Lewis, along with T.S. Eliot, "set the course for Milton Studies for the second half of the twentieth century",[4] and that he "set forth" a "tradition of interpretation" which was later followed by Stanley Fish's book Surprised By Sin.[4] John P. Rumrich made the same assessment of Fish, describing Fish's book as "a methodologically radical update of Lewis's reading of Paradise Lost as a literary monument to mainstream Christianity";[13] Michael Bryson highlights the importance of this in his remark that "even more than Lewis's work, however, the book that has cast the longest shadow over the field of Milton studies—at least in the United States—for the last 45 years is Stanley Fish's Surprised by Sin."[10] Rumrich characterizes this interpretive tradition as "an approach that promises historical fidelity yet at the same time represents Milton as the exponent of a transhistorical Christian tradition."[13]

Criticism

[edit]Helen Gardner claims that "C. S. Lewis's discussion of the varieties of evil disposition shown in the great 'consult' of Book II seems to range very far from what the text presents to our imagination",[12] and that "Lewis's analysis of the successive sins that Eve falls into, ending with Murder, presents us with the abstractions and exaggerations of the moralist in place of Milton's presentation of the events."[12]

Theology

[edit]David Hopkins claims that Lewis's Preface to Paradise Lost gives the impression "that only those who shared Milton's (and Lewis's) Christian faith would be likely to enjoy or respect the poem", but that this is not true, and is contradicted by Lewis himself in certain passages from An Experiment in Criticism.[16]

William Kolbrener regarded Lewis's attempt to acquit Paradise Lost of heresy as unsuccessful, claiming that "Lewis's insistence on an orthodox Milton, like Bentley's before him, can't help but reveal the heretical perspectives, even the passionate and sensual energies, it attempts to repress."[4]

Michael Bryson, in a book titled The Atheist Milton, criticizes Lewis's attempt to "prevent the reader from ever raising certain questions" about Milton's orthodoxy,[10] claiming that Milton "is hardly the spokesperson for the kind of Anglican orthodoxy C.S. Lewis tried to assimilate him to", and claims that "the false simplicity of Lewis's approach" (to such questions as the role of "Disobedience" in the epic, and to the significance of the apple) "is designed, it seems (as it also seems with [David] Urban), to promote a very specific theological agenda."[10]

Portrayal of Satan

[edit]

Regarding the portrayal of Satan, Arnold Stein said that "C. S. Lewis, in reducing Satan's argument to its illogical nonsense, seems to overlook the possibility that Satan may be conscious of what he is saying."[8]

Helen Gardner saw Lewis's analysis of the character of Satan as displaying Lewis's own harsh view of human nature:

Mr. Lewis, in exposing Shelley's misconceptions, has inverted the Romantic attitude, for the effect of his chapter on Satan is to make us feel that because Satan is wicked and wicked with no excuse, he is not to be pitied, but is to be hated and despised. Shelley saw in Satan the indomitable rebel against unjust tyranny, and while regretting the 'taints' in his character excused them. Mr. Lewis, who thinks more harshly of himself and of human nature than Shelley did, exposes Satan with all the energy and argumentative zeal which we used to hear our European Service employing in denouncing the lies of Goebbels and revealing the true nature of the promises of Hitler. Both Shelley's passionate sympathy and Mr. Lewis's invective derive from the same fundamental attitude: "It is we who are Satan."[12]

Margaret Olofson Thickstun also sees Lewis's analysis as a response to Romantic attitudes, and sees support in it for the view that Satan may be redeemed (through apocatastasis):

Surprisingly, support for reading apocastatic potential in Satan's story comes from another extremely orthodox reader of Paradise Lost: C. S. Lewis. Responding to a Romantic tradition that sympathizes with a Satan whom they claim Milton made "more glorious than he intended" (100), Lewis argues against valorizing Satan precisely by emphasizing his interiority. He reminds readers "that the terrible soliloquy in Book IV (32–113) was conceived and in part composed before the first two books. It was from this conception that Milton started" (Lewis 100). Lewis means to enlist this fact to support recognition of Satan's consistency as a character, but it also underscores Milton's theological perspective: Milton conceived Satan, from the start, as a troubled creature with an intense inner life. If Satan is presented in anguish as a warning to sinners not to be like him, if he retains an inner life and personal responsibility, as the poem insists he does, then Satan must still be like humans, capable of ontological change and growth (Robertson 63).[15]

See also

[edit]- Paradise Lost, a 1667 epic poem by John Milton

- Stanley Fish, author who had similar opinions to Lewis on Paradise Lost

References

[edit]- ^ It is still regarded as influential: see Dominic Head, ed. The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English, 3rd ed. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 646.

- ^ a b Lambdin, Laura (2007). Arthurian Writers: A Biographical Encyclopedia (1 ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood. pp. 255, 261. ISBN 978-0313346828.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Lewis, Clive Staples (1969). A Preface to Paradise Lost. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195003451.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kolbrener, William (28 April 2014), "Reception", The Cambridge Companion to Paradise Lost, Cambridge University Press, pp. 195–210, doi:10.1017/cco9781139333719.020, ISBN 978-1-139-33371-9, retrieved 31 August 2023

- ^ Eliot, T. S. (Thomas Stearns) (1936). A note on the verse of John Milton. Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d Jordan, Matthew (2000). Milton and Modernity: Politics, Masculinity and Paradise Lost (1 ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0333746752.

- ^ a b Scully, Stephen (2015). Hesiod's Theogony: from Near Eastern Creation Myths to Paradise Lost (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0190253967.

- ^ a b c d e Stein, Arnold (1953). Answerable Style: Essays on Paradise Lost. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 4, 29, 48, 56. ISBN 978-0816658725.

- ^ Lewalski, Barbara Kiefer (2016). Paradise Lost and the Rhetoric of Literary Forms (1 ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-0691639581.

- ^ a b c d e f Bryson, Michael E. (23 March 2016). The Atheist Milton. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315613796. ISBN 978-1-317-04096-5.

- ^ a b Milton, John; Leonard, John (2003). Paradise Lost. New York: Penguin. pp. Preface. ISBN 9780140424393.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gardner, Helen (1967). A Reading of "Paradise Lost" (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. vii, 11, 14–15, 84–85, 99–100, 113–114, 117. ISBN 978-0198116622.

- ^ a b c Rumrich, John P. (2006). Milton Unbound: Controversy and Reinterpretation (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 4, 29, 34. ISBN 978-0521032209.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Louis (2014). The Cambridge Companion to Paradise Lost (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1107029460.

- ^ a b Thickstun, Margaret Olofson (2007). Milton's Paradise Lost: Moral Education (1 ed.). London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 42, 51. ISBN 978-1403977571.

- ^ Hopkins, David (2013). Reading Paradise Lost (1 ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-118-47100-5.

External links

[edit]- A Preface to Paradise Lost at Faded Page (Canada)