A Home at the End of the World (film)

| A Home at the End of the World | |

|---|---|

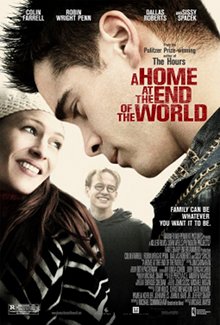

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Mayer |

| Screenplay by | Michael Cunningham |

| Based on | A Home at the End of the World by Michael Cunningham |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Enrique Chediak |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Duncan Sheik |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Independent Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6.5 million |

| Box office | $1.5 million |

A Home at the End of the World is a 2004 American drama film directed by Michael Mayer from a screenplay by Michael Cunningham based on his 1990 novel. It stars Colin Farrell, Robin Wright, Dallas Roberts, and Sissy Spacek.

Plot synopsis

[edit]Bobby Morrow's life in suburban Cleveland has been tinged with tragedy since he was a young boy, losing first his beloved older brother to a freak accident, then his mother to illness, and finally his father. As a rebellious teen, he meets the conservative and gawky Jonathan Glover in high school, and he becomes a regular visitor to the Glover home, where he introduces his friend and his mother Alice to marijuana and the music of Laura Nyro. Jonathan, who is slowly coming out as a homosexual, initiates Bobby into adolescent mutual masturbation during their frequent sleepovers. When Alice catches them both masturbating in a car, Jonathan, embarrassed, tells Bobby he is going to leave as soon as he finishes high school. Alice teaches Bobby how to bake, unintentionally setting him on a career path that eventually takes him to New York City in 1982, where Jonathan is sharing a colorful East Village apartment with bohemian Clare. Bobby moves in, and the three create their own household.

Although Jonathan is openly gay and highly promiscuous, he is deeply committed to Clare and the two have tentatively planned to have a baby. Clare seduces and starts a relationship with Bobby, and she eventually becomes pregnant by him. Their romance occasionally is disrupted by sparks of jealousy between the two men until Jonathan, tired of being the third wheel, disappears without warning. He re-enters their lives when his father Ned dies and Bobby and Clare travel to Phoenix, Arizona for the services. The three take Ned's car back east with them, and they impulsively decide to buy a house near Woodstock, New York, where Bobby and Jonathan open and operate a cafe while Clare raises her daughter.

Jonathan discovers what appears to be a Kaposi's sarcoma lesion on his groin and, although Bobby tries to convince him it's simply a bruise, others soon appear. Clare begins to feel left out, seeing the close relationship Jonathan and Bobby share. One day, she takes the baby for what ostensibly is a brief visit to her mother in Philadelphia, but Bobby and Jonathan accurately suspect she has no intention of returning and Bobby decides to care for Jonathan during his last days. On a cold winter day some months later, Bobby and Jonathan scatter Ned's ashes in the field behind their home, and Jonathan (who now visibly appears to be ill) lets Bobby know he would like his own ashes scattered in the same place, following his now inevitable early death from AIDS.

Cast

[edit]- Colin Farrell as Bobby Morrow

- Erik Scott Smith as young Bobby

- Dallas Roberts as Jonathan Glover

- Harris Allan as young Jonathan

- Robin Wright Penn as Clare

- Sissy Spacek as Alice Glover

- Matt Frewer as Ned Glover

- Wendy Crewson as Isabel Morrow

- Ryan Donowho as Carlton Morrow

- Asia Vieira as Emily

Production

[edit]The film was shot on location in New York City, Phoenix, and Schomberg and Toronto in Ontario, Canada.

The film premiered at the New York Lesbian and Gay Film Festival and was shown at the Nantucket Film Festival, the Provincetown International Film Festival, the San Francisco International Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, and the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Film Festival before going into limited release in the US. It grossed $64,728 on five screens on its opening weekend. It eventually earned $1,029,872 in the US and $519,083 in foreign markets for a total worldwide box office of $1,548,955.[1]

Reception

[edit]On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 50% based on 117 reviews, and an average rating of 5.8/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "A Home at the End of the World aims for profundity, but settles for stale melodrama, yielding a slew of sensitive performances that are nevertheless in service to characters who prove to be ciphers."[2] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 59 out of 100, based on 34 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[3]

A.O. Scott of The New York Times observed, "As a novelist Mr. Cunningham can carry elusive, complex emotions on the current of his lovely, intelligent prose. A screenwriter, though, is more tightly bound to conventions of chronology and perspective, and in parceling his story into discrete scenes, Mr. Cunningham has turned a delicate novel into a bland and clumsy film . . . so thoroughly decent in its intentions and so tactful in its methods that people are likely to persuade themselves that it's better than it is, which is not very good . . . The actors do what they can to import some of the texture of life into a project that is overly preoccupied with the idea of life, but the mannered self-consciousness of the script and the direction keeps flattening them into types."[4]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 3 and ½ stars out of four and wrote, "The movie exists outside our expectations for such stories. Nothing about it is conventional. The three-member household is puzzling not only to us, but to its members. We expect conflict, resolution, an ending happy or sad, but what we get is mostly life, muddling through . . . Colin Farrell is astonishing in the movie, not least because the character is such a departure from everything he has done before."[5]

Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle stated, "What we have here . . . is a movie about a friendship and about the changing nature of families. We also have a movie about what it was like to be a child in the late 1960s, a teenager in the mid-1970s and a young adult in the early 1980s. In these aspects, the film is sensitive, sociologically accurate and emotionally true. But the picture is also the story of one character in particular, Bobby, and when it comes to Bobby, A Home at the End of the World is sappy and bogus." He added, "Farrell is not the first actor anyone would cast as an innocent, and he seems to know that and is keen on making good. His speech is tentative but true. His eyes are darting but soulful. The effort is there, but it's a performance you end up rooting for rather than enjoying, because there's no way to just relax and watch."[6]

Peter Travers of Rolling Stone awarded the film three out of four stars, calling it "funny and heartfelt" and "a small treasure." He added, "Farrell's astutely judged portrayal . . . is a career highlight" and "Stage director Michael Mayer (Side Man) makes a striking debut in film."[7]

David Rooney of Variety called the film "emotionally rich drama" "driven by soulful performances." He added, "Strong word of mouth could help elevate this touching film beyond its core audience of gay men and admirers of the book."[8]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film was cited for Excellence in Filmmaking by the National Board of Review and was nominated for the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Film in Wide Release but lost to Kinsey. Dallas Roberts was nominated for the Gotham Independent Film Award for Breakthrough Actor, and Colin Farrell was nominated for the Irish Film Award for Best Actor.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "A Home at the End of the World". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ "A Home at the End of the World (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved August 10, 2024.

- ^ "A Home at the End of the World Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (July 23, 2004). "FILM REVIEW; How a Big Brother's Sexuality and Death Lead to a Romantic Triangle". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 30, 2004). "A Home at the End of the World". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (July 23, 2004). "Teen makes himself some families / Farrell, Spacek, Wright Penn bring home the goods". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 23, 2004). "A Home at the End of the World". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Rooney, David (June 21, 2004). "A Home at the End of the World". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

External links

[edit]- 2004 films

- 2004 directorial debut films

- 2004 LGBTQ-related films

- 2004 romantic drama films

- American romantic drama films

- American teen LGBTQ-related films

- Films about threesomes

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by Michael Mayer

- Films produced by Christine Vachon

- Films set in New York City

- Films set in Ohio

- Films set in Arizona

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in New York (state)

- Films shot in Ontario

- HIV/AIDS in American films

- Killer Films films

- Films about male bisexuality

- Warner Independent Pictures films

- 2000s English-language films

- Films set in 1982

- Films set in 1974

- 2000s American films

- English-language romantic drama films