1228

Appearance

(Redirected from AD 1228)

| Millennium: | 2nd millennium |

|---|---|

| Centuries: | |

| Decades: | |

| Years: |

| 1228 by topic |

|---|

| Leaders |

| Birth and death categories |

| Births – Deaths |

| Establishments and disestablishments categories |

| Establishments – Disestablishments |

| Art and literature |

| 1228 in poetry |

| Gregorian calendar | 1228 MCCXXVIII |

| Ab urbe condita | 1981 |

| Armenian calendar | 677 ԹՎ ՈՀԷ |

| Assyrian calendar | 5978 |

| Balinese saka calendar | 1149–1150 |

| Bengali calendar | 635 |

| Berber calendar | 2178 |

| English Regnal year | 12 Hen. 3 – 13 Hen. 3 |

| Buddhist calendar | 1772 |

| Burmese calendar | 590 |

| Byzantine calendar | 6736–6737 |

| Chinese calendar | 丁亥年 (Fire Pig) 3925 or 3718 — to — 戊子年 (Earth Rat) 3926 or 3719 |

| Coptic calendar | 944–945 |

| Discordian calendar | 2394 |

| Ethiopian calendar | 1220–1221 |

| Hebrew calendar | 4988–4989 |

| Hindu calendars | |

| - Vikram Samvat | 1284–1285 |

| - Shaka Samvat | 1149–1150 |

| - Kali Yuga | 4328–4329 |

| Holocene calendar | 11228 |

| Igbo calendar | 228–229 |

| Iranian calendar | 606–607 |

| Islamic calendar | 625–626 |

| Japanese calendar | Antei 2 (安貞2年) |

| Javanese calendar | 1136–1137 |

| Julian calendar | 1228 MCCXXVIII |

| Korean calendar | 3561 |

| Minguo calendar | 684 before ROC 民前684年 |

| Nanakshahi calendar | −240 |

| Thai solar calendar | 1770–1771 |

| Tibetan calendar | 阴火猪年 (female Fire-Pig) 1354 or 973 or 201 — to — 阳土鼠年 (male Earth-Rat) 1355 or 974 or 202 |

Year 1228 (MCCXXVIII) was a leap year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

[edit]By place

[edit]Sixth Crusade

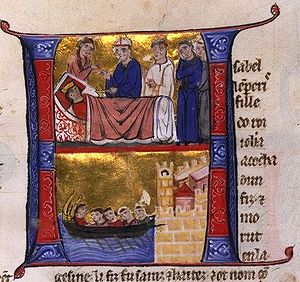

[edit]- Summer – Emperor Frederick II sails from Brindisi with a expeditionary force and arrives in Acre in the Middle East on September 7. He disembarks a well-trained and equipped Crusader army (some 10,000 men and 2,000 knights). After his arrival in Palestine, Frederick is again excommunicated by Pope Gregory IX, for setting out for the Crusade before he has obtained absolution from his previous ex-communication (see 1227). Many of the local nobility, the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller deny him their support for the Crusade. Frederick can only rely on his own army and the Teutonic Knights, whose Grand Master, Hermann von Salza, is his friend.[1]

- Autumn – Frederick II receives an embassy of Sultan Al-Kamil, including Fakhr al-Din ibn as-Shaikh, at the Hospitaller camp at Recordane, near Acre. Meanwhile, Al-Kamil is engaged in suppressing a rebellion in Syria and has concentrated his forces on a siege at Damascus. Frederick is pressed for time, because his army is not large enough for a major campaign. Al-Kamil, who has full control of Jerusalem, starts diplomatic negotiations.[2]

- November – Frederick II puts pressure on the negotiations by a military display. He assembles his Crusader army and marches down the coast to Jaffa – which he proceeds to refortify. At the same moment, Ayyubid forces under An-Nasir Dawud, who are not participating in the revolt at Damascus, move to Nablus, to intercept Al-Kamil's supply lines. Al-Kamil breaks off the negotiations, saying that the Crusaders have pillaged several Muslim villages, and only resumes them again when Frederick pays out compensation to the victims.[2]

Europe

[edit]- April 25 – The 16-year-old Isabella II, Holy Roman Empress and wife of Frederick II, dies after giving birth to her second child, Conrad IV, at Andria. He receives the title King of Jerusalem (as Conrad II) – with Frederick as regent. By his father, Conrad is the grandson of the Hohenstaufen Emperor Henry VI and great-grandson of the late Emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa).

- Emperor Robert I (or Courtenay) dies after a 7-year reign in Morea (Southern Greece). He is succeeded by his 11-year-old brother, Baldwin II, as ruler of the Latin Empire in Constantinople, with John of Brienne as regent.

- King James I (the Conqueror) launches a major offensive against the Almohads in Majorca. At the same moment, Emir Ibn Hud al-Yamadi (confronted by increasing Christian pressure) denounces Almohad rule in Murcia (modern Spain) and acknowledges the Abbasid Caliphate as legitimate overlord, in effect declaring independence.[3] Other notable Christian success: King Alfonso IX of León conquers Mérida.[4]

- December 23 – Stephen of Anagni, Italian papal chaplain, is commissioned to collect a special tax in England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales to finance Gregory X's War of the Keys against Frederick II.

Asia

[edit]- Battle of Bolnisi: Khwarazmian forces led by Sultan Jalal al-Din Mangburni defeat a coalition of Georgians, Kipchaks, Alans, Vainakhs and Laks (some 40,000 men) at Bolnisi (modern Georgia).[5]

- King Sukaphaa establishes the Ahom Dynasty and becomes the first Ahom ruler in Assam (until 1268).

By topic

[edit]Cities and Towns

[edit]- The Transylvanian town of Reghin is first mentioned, in a charter of King Andrew II of Hungary.

Markets

[edit]- The city of Tournai emits its first recorded life annuity, thus confirming a trend of consolidation of public debts started ten years earlier, in Reims.[6]

- The first evidence is uncovered of the use of the Knights Templar as cashiers by King Henry III of England, to safely transfer important sums to the continent, using letters of exchange. This shows that large transfers could take place across Europe, even before the emergence of important networks of Italian merchant-bankers.[7]

Religion

[edit]- July 16 – Saint Francis of Assisi is canonized by Gregory IX.

Births

[edit]- April 25 – Conrad IV (or Conrad II), king of Germany (d. 1254)[8]

- Alfonso of Brienne, Norman nobleman and knight (d. 1270)

- Bartolo da San Gimignano, Italian Franciscan priest (d. 1300)

- Eleanor de Braose, Cambro-Norman noblewoman (d. 1251)

- Ibn Daqiq al-'Id, Egyptian scholar, jurist and writer (d. 1302)

- Shihab al-Din al-Qarafi, Egyptian scholar and jurist (d. 1285)

- Takatsukasa Kanehira, Japanese nobleman (kugyō) (d. 1294)

- Wang Yun, Chinese politician, poet and writer (d. 1304)

Deaths

[edit]- January 13 – Yvette of Huy, Belgian anchoress (b. 1158)

- January 31 – Guy de Montfort, French nobleman and knight

- February 17 – Henry I, German nobleman and knight (b. 1155)

- February 18 – Vladislaus II, margrave of Moravia (b. 1207)

- April 25 – Isabella II, queen and regent of Jerusalem (b. 1212)

- June 18 – Mathilde of Bourbon, French noblewoman (b. 1165)

- July 9 – Stephen Langton, archbishop of Canterbury (b. 1150)

- August 8 – Rujing, Japanese Sōtō Zen patriarch (b. 1163)

- September 24 – Stefan the First-Crowned, king of Serbia

- October 15 – Shichijō-in, Japanese noblewoman (b. 1157)

- October 31 – Eustace of Fauconberg, bishop of London

- December 4 – Bruno von Porstendorf, bishop of Meissen

- December 8 – Geoffrey de Burgh, bishop of Ely (b. 1180)

- Ahmad ibn Munim, Moroccan mathematician and writer

- Anders Sunesen, Danish archbishop and writer (b. 1167)

- Beatrice of Albon, duchess consort of Burgundy (b. 1161)

- Desiderius (Dezső), Hungarian bishop of Csanád and chancellor

- Geoffrey I of Villehardouin, French nobleman and knight

- Henry de Loundres, Norman churchman and archbishop

- Ibn Abi Tayyi, Syrian historian, poet and writer (b. 1180)

- Lady of Neuville ("Eudoxie"), Latin empress consort

- Máel Coluim I, Scottish nobleman and knight (b. 1204)

- Maria of Courtenay, empress consort of the Empire of Nicaea and empress regent of Constantinople

- Reginald de Braose, Norman Marcher Lord (b. 1182)

- Robert I (Courtenay), Latin Emperor of Constantinople

- Robert de Vieuxpont (or Vipont), Anglo-Norman landowner

- Stephen Devereux, Norman Marcher Lord (b. 1191)

- Zhang Congzheng, Chinese physician (b. 1156)

References

[edit]- ^ Steven Runciman (1952). A History of The Crusades. Vol III: The Kingdom of Acre, p. 154. ISBN 978-0-241-29877-0.

- ^ a b Steven Runciman (1952). A History of The Crusades. Vol III: The Kingdom of Acre, p. 156. ISBN 978-0-241-29877-0.

- ^ Linehan, Peter (1999). "Chapter 21: Castile, Portugal and Navarre". In Abulafia, David (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History c.1198-c.1300. Cambridge University Press. pp. 668–699 [672]. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- ^ Picard, Christophe (2000). Le Portugal musulman (VIIIe-XIIIe siècle. L'Occident d'al-Andalus sous domination islamique. Paris: Maisonneuve & Larose. p. 110. ISBN 2-7068-1398-9.

- ^ Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, p. 124. London: reaktion Books. ISBN 1-780-23030-3.

- ^ Zuijderduijn, Jaco (2009). Medieval Capital Markets. Markets for renten, state formation and private investment in Holland (1300-1550). Leiden/Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00417565-5.

- ^ Ferris, Eleanor (1902). "The Financial Relations of the Knights Templars to the English Crown". American Historical Review. 8 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/1832571. JSTOR 1832571.

- ^ "Conrad IV | king of Germany". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved February 14, 2020.