2018 Bavarian state election

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

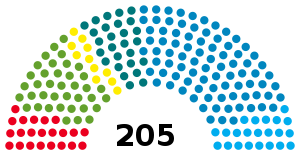

205 seats in the Landtag of Bavaria (including 25 overhang and leveling seats) 103 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered | 9,479,428 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 6,852,036 (72.3%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

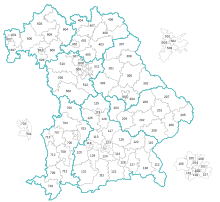

Map of the election, showing the winner of each single-member district and the distribution of list seats in the constituencies. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2018 Bavarian state election took place on 14 October 2018 to elect the 180 members of the 18th Landtag of Bavaria.[1] The outgoing government was a majority of the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CSU), led by Minister President Markus Söder.

The CSU recorded its worst result since 1950 with 37% of votes, a decline of over ten percentage points, although it remained by far the largest party in the Landtag. The SPD, which had previously been the second largest party, fell to fifth place with just 10%. The Greens gained 9 points and emerged as the second strongest party with 17.5%. The Free Voters of Bavaria (FW) gained 2.6 points and finished third with 11.6% of the total vote. The Alternative for Germany (AfD), which ran in Bavaria for the first time, placed fourth with 10%. The Free Democratic Party (FDP), which failed to enter the Landtag in 2013, narrowly re-entered with 5.1%, becoming the smallest party. Turnout rose to 72%, up 9 points from under 64% in 2013.[2]

The election was influenced by the condition of the federal CDU/CSU–SPD government following two crises in the preceding months: the so-called asylum quarrel in June and July followed by the controversy around Hans-Georg Maaßen in September. CSU leader Horst Seehofer played a major role in both events. Four days before the Bavarian election, federal SPD leader Andrea Nahles criticised Chancellor Angela Merkel, accusing her of a "lack of leadership".[3]

As a result of the election, the CSU lacked a majority and formed a coalition government with the Free Voters.

Election date and preparation deadlines

[edit]According to the Bavarian Constitution, the election must be held on a Sunday "at the earliest 59 months, at the latest 62 months" after the preceding state elections[4] which took place on 15 September 2013. This would theoretically allow an election date between 19 August and 11 November 2018, but in practice the elections since 1978 have always taken place between mid-September and mid-October.[5] The Bavarian state government proposed 14 October 2018 as the election date on 9 January 2018[1] and officially set it on 20 February after hearing the parties to the state parliament.[6]

The deadline for determining the population figures, which are decisive for the distribution of the 180 Landtag mandates among the seven Bavarian administrative districts and a possible new division of the constituencies, was 15 June 2016 (33 months after the election of the previous Landtag).[7] On this basis, the Bavarian Ministry of the Interior had to submit a constituency report to the Landtag until 36 months after the election[8] This was done on 6 September 2016.

Delegates to the internal constituency meetings could be appointed at the earliest 43 months after the preceding election, i.e. since 16 April 2017. The actual district candidates had been eligible since 16 July 2017.[9][10] The parties and other organised electoral groups which had not been represented continuously in the Bavarian Land Parliament or in the German Bundestag since their last election on the basis of their own election proposals (CDU, CSU, SPD, Free Voters of Bavaria, Alliance 90/The Greens, FDP, Die Linke, AfD) had to notify their intention to participate to the State Election Commissioner by the 90th day before the election, i.e. by 16 July 2018 at the latest.[11] The actual election proposals and any necessary signatures had to be submitted by 2 August 2018.[12]

Electoral system

[edit]

Bavaria, in line with the rest of the country, uses mixed-member proportional representation to elect its members of the Landtag. Party representation is not apportioned statewide, the distribution of seats takes place separately within the seven administrative districts (Regierungsbezirke), which are referred to in the electoral law as constituencies. The constituencies are divided into districts in which one member is directly elected. The number of single member districts is about half the number of seats in the constituency. In contrast to the Bundestag election law, the distribution of seats by proportional representation takes into account the parties' aggregate first (district) votes combined with their second (constituency) votes, i.e. both the first and second votes affect the distribution of seats in the Landtag, as opposed to just the second votes, which is the norm elsewhere in the country. If a party wins more district seats in a constituency than it would be entitled to based on a strictly proportional system (these extra seats are termed overhang seats), this seats are added to the constituency. To compensate the other parties for the overhang, leveling seats are added at the constituency level too. There is no statewide adjustment of the seats. Only parties and groups of voters who obtain at least 5% of the total votes (sum of first and second votes) in Bavaria participate in the distribution of seats. This threshold also applies to winning single-member districts; a party will forfeit all its district seats that it won if the party did not meet the 5% statewide threshold, with the forfeited district seats going to the second-place candidate.

Unlike the other German states (and also countries using MMP), Bavaria uses an open-list system for its party-list seats. Voters not only cast a vote for a candidate in their district, but they also cast a vote for a list candidate in their region. For the distribution of list seats, all district candidates are also constituency candidates with their parties. The party may also nominate regional-only candidates. To prevent double voting, the constituency ballots in each district omit the candidates running in that district. A candidate (if he or she did not win his or her district) is ranked within his or her list by the number of first votes he or she receives within the district plus the number of second votes he or she receives from voters elsewhere in the region. In this manner, voters collectively can produce a list that is different from what the party submitted, which can result in the defeat of candidates that would have been elected (and vice versa) had the election taken place under a closed-list system.[13]

Boundary changes

[edit]

In the statutory constituency report of September 2016, the state government stated that the numerical distribution of the 180 state parliament seats among the constituencies would have to be changed due to changes in the number of inhabitants. It was recommended that a seat previously to be awarded in the Lower Franconia constituency be allocated to the Upper Bavaria constituency.

Within Upper Bavaria, the additional seat was used to reshape the single member districts in the state capital of Munich, as two of them — Giesing and Milbertshofen[14] — exceeded the average population by more than 15 percent. Upper Bavaria now has 31 single member districts for the 2018 elections, nine of which are accounted for by the state capital.

Seats and single member districts are distributed as follows:[15]

| Constituency | Seats | Single-member districts |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Bavaria | 61 | 31 |

| Lower Bavaria | 18 | 9 |

| Upper Palatinate | 16 | 8 |

| Upper Franconia | 16 | 8 |

| Middle Franconia | 24 | 12 |

| Lower Franconia | 19 | 10 |

| Swabia | 26 | 13 |

| Total | 180 | 91 |

Gerrymandering

[edit]In March 2017, the CSU used the mandatory redistricting to redraw Munich's electoral districts. In this, they were accused of gerrymandering; redistricting created a new Stimmkreis München-Mitte that was packing all parts of Munich that at the time favored the SPD. The Greens eventually won the district by a huge margin. The CSU was only partly successful in their gerrymandering, as they still lost four districts in Munich that were drawn to their advantage.

Starting position

[edit]Since the state elections in Bavaria in 2013, the CSU again had the absolute majority of seats, as it did from 1962 to 2008. The CSU also held the position of the senior partner in all but one governing coalition in Bavaria since the end of World War II, including every coalition since 1958. In December 2017, however, Minister President of Bavaria Horst Seehofer (CSU) finally declared his renunciation of the top candidate in the state elections in Bavaria in 2018, partly due to the poor performance of the CSU in the 2017 Bundestag elections. In March 2018, he also resigned from his office as Minister President of Bavaria before the end of the parliamentary term. The former Bavarian Finance Minister Markus Söder was elected as the new top CSU candidate and later also as Minister President of Bavaria in the state parliament.

Campaign

[edit]CSU

[edit]In 2018, the CSU Markus Söder's government enacted the Kreuzpflicht, an obligation to display crosses at the entrance of public buildings. Söder has stated that the crosses are not to be seen as Christian symbols, but as symbols of Bavarian cultural identity.[16]

Some observers have described the Kreuzpflicht as a measure to appeal to voters deserting the Christian democratic conservative CSU for the right-wing nationalist AfD party. Also the CSU interior minister Horst Seehofer has taken a harder line on immigration.[17]

Parties

[edit]The table below lists parties represented in the 17th Landtag of Bavaria.

| Name | Ideology | Leader(s) | 2013 result | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes (%) | Seats | |||||

| CSU | Christian Social Union in Bavaria Christlich-Soziale Union in Bayern |

Christian democracy | Markus Söder | 47.7% | 101 / 180

| |

| SPD | Social Democratic Party of Germany Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands |

Social democracy | Natascha Kohnen | 20.6% | 42 / 180

| |

| FW | Free Voters of Bavaria Freie Wähler Bayern |

Regionalism | Hubert Aiwanger | 9.0% | 19 / 180

| |

| Grüne | Alliance 90/The Greens Bündnis 90/Die Grünen |

Green politics | Katharina Schulze Ludwig Hartmann |

8.6% | 18 / 180

| |

Leaders' debate

[edit]A leaders' debate between Minister President Markus Söder (CSU) and Ludwig Hartmann (Alliance 90/The Greens) took place on 26 September 2018. The Bayerischer Rundfunk justified the party selection with the result of the Bayerntrend of September 12, 2018, according to which CSU and Greens can hope for the most votes in the election. SPD Secretary-General Uli Grötsch described this decision as "completely absurd".[18] A programme with representatives of the other five parties, whose survey results were above or close to the five percent hurdle, followed on 28 September 2018: Natascha Kohnen (SPD), Hubert Aiwanger (Free Voters), Martin Sichert (AfD), Martin Hagen (FDP) and Ates Gürpinar (The Left). The first programme was moderated by BR editor-in-chief Christian Nitsche, the second by Ursula Heller.

Opinion polling

[edit]| Polling firm | Fieldwork date | Sample size |

CSU | SPD | FW | Grüne | FDP | Linke | AfD | Others | Lead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 state election | 14 Oct 2018 | – | 37.2 | 9.7 | 11.6 | 17.6 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 10.2 | 5.4 | 19.6 |

| Forschungsgruppe Wahlen | 10–11 Oct 2018 | 1,075 | 34 | 12 | 10 | 19 | 5.5 | 4 | 10 | 5.5 | 15 |

| Civey | 6–10 Oct 2018 | 5,063 | 32.9 | 11.0 | 9.8 | 18.5 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 12.8 | 5.2 | 14.4 |

| INSA | 2–8 Oct 2018 | 1,707 | 33 | 10 | 11 | 18 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 14 | 4 | 15 |

| Forschungsgruppe Wahlen | 1–4 Oct 2018 | 1,122 | 35 | 12 | 10 | 18 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 10 | 5 | 17 |

| Infratest dimap | 1–2 Oct 2018 | 1,002 | 33 | 11 | 11 | 18 | 6 | 4.5 | 10 | 6.5 | 15 |

| GMS | 20–26 Sep 2018 | 1,004 | 35 | 13 | 10 | 16 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 5 | 19 |

| INSA | 21–25 Sep 2018 | 1,064 | 34 | 11 | 10 | 17 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 4 | 17 |

| Civey | 19–23 Sep 2018 | 5,061 | 36.0 | 12.0 | 8.6 | 17.9 | 5.0 | 3.3 | 13.2 | 4.0 | 18.1 |

| Forschungsgruppe Wahlen | 17–19 Sep 2018 | 1,114 | 35 | 13 | 11 | 18 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 17 |

| Infratest dimap | 5–10 Sep 2018 | 1,000 | 35 | 11 | 11 | 17 | 5 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 18 |

| GMS | 4–10 Sep 2018 | 1,006 | 36 | 12 | 7 | 16 | 6 | 4 | 14 | 5 | 20 |

| Civey | 30 Aug–9 Sep 2018 | 5,046 | 35.8 | 12.1 | 8.1 | 16.5 | 5.8 | 2.7 | 13.7 | 5.3 | 19.3 |

| INSA | 23–27 Aug 2018 | 1,033 | 36 | 13 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 21 |

| Civey | 15–26 Aug 2018 | 5,049 | 37.8 | 11.8 | 8.1 | 15.1 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 13.5 | 5.1 | 22.7 |

| Civey | 30 Jul–13 Aug 2018 | 5,047 | 38.1 | 12.3 | 7.3 | 15.0 | 5.3 | 2.7 | 15.2 | 4.1 | 22.9 |

| Forsa | 25 Jul–9 Aug 2018 | 1,105 | 37 | 12 | 8 | 17 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 20 |

| GMS | 25–31 Jul 2018 | 1,004 | 39 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 13 | 5 | 25 |

| Infratest dimap | 11–16 Jul 2018 | 1,003 | 38 | 13 | 9 | 16 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 22 |

| GMS | 5–11 Jul 2018 | 1,007 | 39 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 25 |

| Forsa | 4–6 Jul 2018 | 1,003 | 38 | 12 | 8 | 15 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 4 | 23 |

| Civey | 23 Jun–5 Jul 2018 | 5,093 | 42.5 | 13.7 | 6.0 | 13.2 | 5.2 | 2.8 | 13.1 | 3.5 | 28.8 |

| INSA | 25–27 Jun 2018 | 1,231 | 41 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 14 | 5 | 27 |

| Forsa | 21–22 Jun 2018 | 1,033 | 40 | 13 | 8 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 26 |

| Civey | 19 May–7 Jun 2018 | 5,066 | 41.1 | 13.4 | 7.0 | 12.6 | 4.8 | 3.5 | 13.5 | 4.1 | 27.6 |

| GMS | 11–16 May 2018 | 1,005 | 42 | 13 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 29 |

| Civey | 23 Apr–11 May 2018 | 5,082 | 42.1 | 13.7 | 6.6 | 13.5 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 12.0 | 4.1 | 28.4 |

| Infratest dimap | 22–27 Apr 2018 | 1,002 | 41 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 27 |

| GMS | 20–26 Apr 2018 | 1,002 | 44 | 14 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 5 | 30 |

| INSA | 17–20 Apr 2018 | 1,005 | 42 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 29 |

| Civey | 19 Mar–5 Apr 2018 | 5,048 | 44.5 | 14.8 | 6.5 | 11.3 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 11.9 | 4.0 | 29.7 |

| GMS | 16–21 Mar 2018 | 1,004 | 43 | 15 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 28 |

| Civey | 2–15 Mar 2018 | 5,004 | 41.4 | 14.2 | 8.4 | 12.0 | 4.6 | 3.0 | 12.1 | 4.3 | 27.2 |

| Civey | 12–26 Feb 2018 | 5,040 | 39.4 | 13.4 | 8.6 | 12.2 | 5.3 | 3.5 | 12.3 | 5.3 | 26.0 |

| Forsa | 8–22 Feb 2018 | 1,027 | 42 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 28 |

| GMS | 1–9 Feb 2018 | 1,510 | 40 | 15 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 25 |

| Civey | 6–16 Jan 2018 | 5,040 | 39.9 | 14.8 | 7.6 | 11.4 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 13.1 | 4.0 | 21.1 |

| Infratest dimap | 3–8 Jan 2018 | 1,002 | 40 | 16 | 7 | 14 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 24 |

| GMS | 27 Dec 2017–1 Jan 2018 | 1,007 | 39 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 7 | 24 |

| INSA | 12–13 Dec 2017 | 1,003 | 40 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 25 |

| Civey | 24 Nov–13 Dec 2017 | 5,019 | 36.7 | 16.0 | 8.3 | 12.1 | 7.1 | 2.9 | 12.9 | 4.0 | 20.7 |

| GMS | 27–29 Nov 2017 | 1,006 | 37 | 15 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 14 | 6 | 22 |

| Civey | 16 Oct–16 Nov 2017 | 5,034 | 38.8 | 14.9 | 6.5 | 10.8 | 8.0 | 3.6 | 13.5 | 3.9 | 23.9 |

| Forsa | 6–9 Nov 2017 | 1,017 | 38 | 17 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 3 | 21 |

| INSA | 2–3 Nov 2017 | 1,033 | 37 | 17 | 8 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 20 |

| GMS | 13–18 Oct 2017 | 1,004 | 41 | 15 | 6 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 26 |

| Civey | 25 Sep–13 Oct 2017 | 5,043 | 40.7 | 14.1 | 7.0 | 12.4 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 11.3 | 4.0 | 26.6 |

| 2017 federal election | 24 Sep 2017 | – | 38.8 | 15.3 | 2.7 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 6.1 | 12.4 | 4.8 | 23.5 |

| Infratest dimap | 4–9 Jan 2017 | 1,001 | 45 | 14 | 7 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 31 |

| GMS | 27 Oct–2 Nov 2016 | 1,005 | 44 | 18 | 6 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 5 | 26 |

| GMS | 8–12 Oct 2016 | 1,013 | 45 | 19 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 26 |

| GMS | 9–14 Sep 2016 | 1,015 | 45 | 18 | 5 | 12 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 27 |

| Forsa | 4–15 Jul 2016 | 1,008 | 43 | 16 | 6 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 27 |

| Infratest dimap | 11–14 Jul 2016 | 1,000 | 45 | 17 | 5 | 13 | 4 | – | 9 | 7 | 28 |

| GMS | 8–13 Jul 2016 | 1,015 | 47 | 17 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 30 |

| INSA | 17 May–8 Jun 2016 | 1,698 | 47.5 | 17.5 | 4.5 | 11.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 7 | 5 | 30 |

| Forsa | 23 May–3 Jun 2016 | 1,010 | 40 | 16 | 6 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 24 |

| GMS | 27 May–1 Jun 2016 | 1,021 | 48 | 17 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 4 | 31 |

| GMS | 15–19 Apr 2016 | 1,018 | 48 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 32 |

| GMS | 14–16 Mar 2016 | 1,015 | 48 | 16 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 32 |

| GMS | 12–17 Feb 2016 | 1,010 | 46 | 17 | 5 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 6 | 29 |

| Infratest dimap | 7–11 Jan 2016 | 1,000 | 47 | 16 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 31 |

| GMS | 28 Dec 2015–3 Jan 2016 | 1,019 | 45 | 19 | 6 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 26 |

| GMS | 12–18 Nov 2015 | 1,016 | 46 | 18 | 5 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 28 |

| GMS | 1–7 Oct 2015 | 1,019 | 46 | 18 | 6 | 12 | 6 | – | 5 | 7 | 28 |

| Forsa | 23 Sep–2 Oct 2015 | 1,007 | 43 | 19 | 5 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 24 |

| GMS | 10–16 Sep 2015 | 1,007 | 49 | 20 | 6 | 10 | 5 | – | 2 | 8 | 29 |

| GMS | 16–22 Jul 2015 | 1,011 | 47 | 20 | 6 | 10 | 5 | – | 2 | 10 | 27 |

| GMS | 18–24 Jun 2015 | 1,012 | 48 | 19 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 29 |

| INSA | 5–15 Jun 2015 | 651 | 46 | 20 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 26 |

| GMS | 7–13 May 2015 | 1,008 | 48 | 18 | 7 | 10 | 4 | – | 5 | 8 | 30 |

| GMS | 9–15 Apr 2015 | 1,016 | 48 | 19 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 29 |

| Forsa | 19–31 Mar 2015 | 1,266 | 47 | 19 | 7 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 28 |

| Infratest dimap | 8–12 Jan 2015 | 1,004 | 46 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 27 |

| GMS | Nov 2014 | 2,000 | 49 | 18 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 31 |

| pollytix | 13–23 Nov 2014 | 1,700 | 47 | 20 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 27 |

| Emnid | 1 Oct–4 Nov 2014 | 2,114 | 48 | 18 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 30 |

| 2014 European election | 25 May 2014 | – | 40.5 | 20.1 | 4.3 | 12.1 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 20.4 |

| Infratest dimap | 10–12 Mar 2014 | 1,002 | 46 | 18 | 12 | 11 | – | – | – | 13 | 28 |

| Infratest dimap | 9–13 Jan 2014 | 1,004 | 49 | 19 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 2 | – | 7 | 30 |

| 2013 federal election | 22 Sep 2013 | – | 49.3 | 20.0 | 2.7 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 3.8 | 4.3 | 6.4 | 29.3 |

| 2013 state election | 15 Sep 2013 | – | 47.7 | 20.6 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 2.1 | – | 8.7 | 27.1 |

Policy areas relevant to elections

[edit]On behalf of the RTL/n-tv Trendbarometer, Forsa Institute interviewed the survey participants about the "biggest problems at state level".[19] In Bavaria, 34 percent of those surveyed named the CSU and Prime Minister Markus Söder, 28 percent named refugees, and 26 percent named "the situation on the housing market".[20]

Infratest dimap asked respondents to the ARD primary election survey which topic is very important for their election decision. In the order of most percentage points these were school and education policy (55%), nature conservation in Bavaria (46%), creation of affordable housing (45%), reduction of injustice in society (41%), security and police (40%), regulation of immigration (39%), the behaviour of Horst Seehofer in the federal government (26%), the cooperation of CDU, CSU and SPD in the federal government (21%).[21]

Voter turnout

[edit]The voter turnout in the city of Munich remained high. Until 2 p.m. it was 54.6 percent including the postal voters. In 2013, the turnout at that time was 49.7 percent.[22] The final total turnout was recorded as 72.3% of eligible voters.[2]

Election result

[edit] | ||||||||

| Party | Ideology | Votes | Votes % (change) | Seats (change) | Seats % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Social Union (CSU) | Christian democracy | 5,046,081 | 37.2% | −10.5pp | 85 | −16 | 41.5% | |

| Alliance '90/The Greens (Grünen) | Green politics | 2,392,356 | 17.6% | +9.0pp | 38 | +20 | 18.5% | |

| Free Voters (FW) | Regionalism | 1,572,792 | 11.6% | +2.6pp | 27 | +8 | 13.2% | |

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | German nationalism | 1,388,622 | 10.2% | +10.2pp | 22 | +22 | 10.7% | |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | Social democracy | 1,309,078 | 9.7% | −11.0pp | 22 | −20 | 10.7% | |

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | Liberalism | 690,499 | 5.1% | +1.8pp | 11 | +11 | 5.4% | |

| The Left (Die Linke) | Democratic socialism | 437,888 | 3.2% | +1.1pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Bavaria Party (BP) | Bavarian nationalism | 231,731 | 1.7% | −0.4pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Ecological Democratic Party (ÖDP) | Green conservatism | 211,951 | 1.6% | −0.5pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Pirate Party (Piraten) | Pirate politics | 59,145 | 0.4% | −1.5pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Party for Franconia (Die Franken) | Regionalism | 31,453 | 0.2% | −0.5pp | 0 | ±0 | 0% | |

| Others | 193,151 | 0 | ±0 | 0% | ||||

| Total | 13,564,747 | 100.0% | 205 | +25 | ||||

Aftermath

[edit]Preferred coalition polling

[edit]The percentages indicate the proportion of respondents who would most like the particular coalition available for selection. The percentages do not sum to 100% due to respondents who did not indicate a preference.

| Institute | Date | CSU only | CSU Grüne |

Grüne SPD FDP FW |

CSU AfD |

CSU FW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civey[23] | 18 September 2018 | 19.3 % | 15.4% | 15.3% | 13.7% | 10.1% |

State government formation

[edit]Before the election, CSU faction leader Thomas Kreuzer declared that the CSU would not form a coalition with the AfD or the Greens after the election.[24]

The CSU agreed on a coalition deal to govern with the Free Voters of Bavaria on 4 November 2018.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wahltermine

- ^ a b c Landtagswahl am 14. Oktober 2018 Archived 2018-12-08 at the Wayback Machine. Der Landeswahlleiter des Freistaates Bayern. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ Nahles kritisiert Merkel, Der Spiegel, 10 October 2018

- ^ Artikel 16 (1) Satz 3 Bayerische Verfassung

- ^ Landeswahlleiter Bayern: Übersicht über Wahltermine und -ergebnisse, retrieved 7 September 2016

- ^ Bayerischer Rechts- und Verwaltungsreport: Staatsregierung setzt 14.10.2018 als Termin für Landtagswahl fest, Report of 20 February 2018.

- ^ Artikel 21 (1) Bayerisches Landeswahlgesetz

- ^ Artikel 5 (5) Bayerisches Landeswahlgesetz

- ^ Landeswahlleiter: Landtagswahl 2018: Fristen für die Aufstellung der Bewerber

- ^ Artikel 28 (2) Bayerisches Landeswahlgesetz

- ^ Art. 24 LWG

- ^ Art. 26 LWG

- ^ Day, Wilf (2016-01-08). "Wilf Day's Blog: Open-list mixed member proportional models: The Bavarian example". Wilf Day's Blog. Retrieved 2018-12-26.

- ^ Bavarian State Government: Bericht der Bayerischen Staatsregierung über die Veränderung der Einwohnerzahlen in den Wahl- und den Stimmkreisen nach Art. 5 Abs. 5 des Landeswahlgesetzes vom 6. September 2016 Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 7 September 2016

- ^ "Gesetz zur Änderung des Landeswahlgesetzes" (PDF). Bayerischer Landtag. 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2018-03-08.

- ^ "Bavarian leader orders Christian crosses on all state buildings". the Guardian. Agence France-Presse. 2018-04-25. Retrieved 2018-05-31.

- ^ "Merkel's migration plan 'rejected' by hardline minister".

- ^ Schwarz gegen Grün faz.net, 18. September 2018

- ^ "Viele Bayern halten Markus Söder für ein Problem". Die Zeit. 2018-08-13. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ "Bayern sehen CSU und Söder als Problem". n-tv. 2018-08-13. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- ^ Ellen Ehni (2018-10-04). "CSU sackt auf 33 Prozent". Tagesschau.de. Retrieved 2018-10-05.

- ^ "Münchens Wahlbeteiligung mittlerweile bei 54,6 Prozent". welt.de. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Alleinregierung der CSU ist beliebter als Koalition, focus.de, retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ CSU schließt schwarz-grüne Koalition in Bayern aus. Welt Online, 8. September 2018.

- ^ Bavarian conservatives and Free Voters reach coalition deal. POLITICO (Europe edition). Author - Joshua Posaner. Published 4 November 2018. Updated 5 November 2018. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

External links

[edit]- Official results (in German)