1888 in Italy

| |||||

| Decades: | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| See also: | |||||

Events from the year 1888 in Italy

Kingdom of Italy

[edit]- Monarch – Umberto I (1878–1900)

- Prime Minister – Francesco Crispi (1887–1891)

The total population of Italy in 1888 (within the current borders) was 31.160 million.[1] Life expectancy in 1888 was 37.0 years.[2]

Events

[edit]

As prime minister Crispi pursued an aggressive foreign policy and assumed a resolute attitude towards France. The Triple Alliance (1882) committed Italy to a possible war with France, requiring a vast increase in the already heavy Italian military expenditure, making the alliance unpopular in Italy.[3] As part of his anti-French foreign policy, Crispi began a tariff war with France in 1888.[4] The Franco-Italian trade war was an economic disaster for Italy which over a ten-year period cost two billion lire in lost exports, and ended in 1898 with the Italians agreeing to end their tariffs on French goods in exchange for the French ending their tariffs on Italian goods.[5]

February

[edit]- In February an Italo-German military convention was signed. If the Triple Alliance would be at war with France and Russia, Italy's main effort would be to send five army corps and three cavalry divisions to fight on the Rhine. An indiscretion at the Italian court revealed the existence of the convention to the French and the delegation that negotiated a Franco-Italian trade agreement immediately left Rome, declaring that no trade treaty would be signed while Italy remained in the Triple Alliance.[6]

March

[edit]- 1 March — As a reaction to the strict protectionist tariff established in Italy in July 1887, France introduced a discriminatory trade tariff, and Italy raised their duties on French goods by 50%; initiating a full-scale tariff war.[6]

The short-term effects of the tariff war would be dramatic: "Trade between the two countries was halved. Italian exports to France fell from an average of 444 million lire in 1881-87 to an average of 165 million lire in 1888-90; the French share of Italian exports fell from 41 per cent to 18 per cent. Imports from France went down from 307 million to 164 million lire. Only about one-third of the lost export market could be made up elsewhere. Silk and wine were particularly affected, although rice, dairy produce and cattle exports all suffered."[7]

July

[edit]- In July, Italian troops of General Antonio Baldissera began operations to extend Italian colonial possessions in Italian Eritrea, starting from the already acquired Massawa they targeted the plateau cities of Keren and Asmara.

August

[edit]- 8 August — Battle of Segheneyti, a clash fought between Italian troops and Abyssinian irregulars towards the end of the Italo-Ethiopian War of 1887-1889. The battle resulted in the destruction of Italian attachment that was deployed to Segheneyti. The defeat, though minor, drew heavy criticism towards general Baldissera.[8]

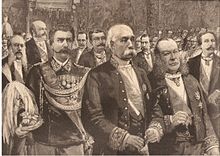

October

[edit]- 11 October — German Emperor Wilhelm II in Rome on an official state visit. Visiting the Italian King Umberto I in Rome would be regarded as recognizing his right to rule the Holy City, while the Vatican did not recognise the Italian king's right to rule in Rome. To appease the situation, Wilhelm II also met Pope Leo XIII the next day.[9]

December

[edit]- 22 December – The Crispi government enacted the first Italian law for the national healthcare system including cremation[10] after a cholera pandemic in 1884–1885 killed approximately 50,000 persons,[11][12] with a serious outbreak in the city of Naples in August–September 1884, killing 8,000 persons.[13][14]

- 30 December – The Crispi government enacted the first Italian law introducing timid regulations on migrant protection to regulate expanding emigration from Italy. The Emigration Act of 1888 is also known as the Crispi Law on emigration. The law proclaimed the freedom to emigrate, as long as those intending to leave were in order with the military draft. It regulated the activities of emigration agents and regulated the contract of maritime transport. Married women could leave but only with their husband's consent.[15] Transatlantic emigration had risen from about 20,000 a year before 1879 to 130,000 in 1887, and to nearly 205,000 in 1888.[16]

Births

[edit]- 27 February – Roberto Assagioli, psychiatrist who founded the psychological movement known as psychosynthesis (died 1974)

- 30 April – Antonio Sant'Elia, architect and a key member of the Futurist movement in architecture (died 1916)

- 14 July – Scipio Slataper, writer (died 1915)

- 30 August – Eduardo Ciannelli, baritone and character actor with a long career in American films (died 1969)

- 15 September – Antonio Ascari, Grand Prix motor racing champion (died 1925)

- 10 November – Edvige Mussolini, the younger sister of Benito Mussolini (died 1952)

- 30 December – Mario Carli, poet, novelist, essayist and journalist (died 1935)

Deaths

[edit]- 31 January – Don Bosco, Catholic priest, educator, writer, and saint who dedicated his life to the betterment and education of street children, juvenile delinquents, and other disadvantaged youth (born 1815)

- 29 February – Jacques Savorgnan de Brazza, naturalist, mountaineer and explorer (born 1859)

- 25 March – Francesco Faà di Bruno, priest and advocate of the poor, and leading mathematician of his era (born 1825)

- 17 May – Giacomo Zanella, poet (born 1820)

- 17 October – Carlo Felice Nicolis, conte di Robilant, diplomat and minister for foreign affairs in the Depretis cabinet (1885–1887) (born 1826)

- 26 December – Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, newspaper editor, lawyer and diplomat (born 1817)

References

[edit]- ^ "L'Italia in 150 anni. Sommario di statistiche storiche 1861–2010" (PDF). Istat. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Life expectancy". Our World in Data. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Mack Smith, Italy and Its Monarchy, p.92

- ^ Mack Smith, Italy and Its Monarchy, p.107

- ^ Mack Smith, Italy and Its Monarchy, p.134

- ^ a b Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, pp. 134

- ^ Clark, Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present, p. 117

- ^ G. N. Sanderson (1969). "Conflict and Co-Operation Between Ethiopia and the Mahdist State, 1884-1898". Sudan Notes and Records. 50 (1). University of Khartoum: 27.

- ^ Kertzer, Prisoner of the Vatican, pp. 253-255

- ^ "Ordinamento dell'amministrazione sanitaria del Regno" [Law n° 5849 of 22 December 1888]. Gazzetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia (in Italian) (301). Rome: 5802. 24 December 1888. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. (article 50)

- ^ Aldo Alessandro Mola [in Italian] (8 March 2020). "Nacque per l'incubo del colera la prima legge sanitaria d'Italia (1888)".

- ^ Kohn, Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence, p. 170

- ^ Snowden, Naples in the time of cholera, 1884-1911, p. 104

- ^ Seton-Watson, Italy from liberalism to fascism, p. 90

- ^ "Italian emigration policy during the Great Migration Age, 1888–1919: the interaction of emigration and foreign policy". Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 21:5, 723-746. doi:10.1080/1354571X.2016.1242260.

- ^ Clark, Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present, p. 39

Sources

[edit]- Clark, Martin (2008). Modern Italy, 1871 to the Present. Harlow/New York: Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-2352-4.

- Kertzer, David I. (2004). Prisoner of the Vatican: The Popes' Secret Plot to Capture Rome from the New Italian State. Boston, MD: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-22442-4.

- Kohn, George C. (2001). Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-4263-2.

- Mack Smith, Denis (2001). Italy and Its Monarchy. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05132-8.

- Seton-Watson, Christopher (1967). Italy from liberalism to fascism, 1870–1925. London: Methuen & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-416-18940-7.

- Snowden, Frank M. (1995). Naples in the time of cholera, 1884-1911. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-585-13106-1.