Allylestrenol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Gestanin, Gestanon, Perselin, Turinal, others |

| Other names | Allyloestrenol; SC-6393; Org AL-25; 3-Deketo-17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone; 17α-Allylestr-4-en-17β-ol; 17α-(Prop-2-en-1-yl)estr-4-en-17β-ol |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | "Considerable"[1][2] (and low affinity for SHBG)[3] |

| Metabolism | Liver (reduction, hydroxylation, conjugation; CYP3A4)[1][2][5] |

| Metabolites | • 17α-Allyl-19-NT[3][1][2] |

| Elimination half-life | "Several hours" or 10 hours[4][1][2] |

| Excretion | Urine (as conjugates)[1][2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.440 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

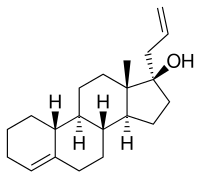

| Formula | C21H32O |

| Molar mass | 300.486 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Allylestrenol, sold under the brand names Gestanin and Turinal among others, is a progestin medication which is used to treat recurrent and threatened miscarriage and to prevent premature labor in pregnant women.[6][7][8] However, except in the case of proven progesterone deficiency, its use for such purposes is no longer recommended.[6] It is also used in Japan to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) in men.[9][10][11] The medication is used alone and is not formulated in combination with an estrogen.[12] It is taken by mouth.[13]

Side effects of allylestrenol are few and have not been well-defined, but are assumed to be similar to those of related medications.[14] Allylestrenol is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.[15] It has no other important hormonal activity.[3][16] The medication is a prodrug of 17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone (3-ketoallylestrenol) in the body.[17][18][3]

Allylestrenol was first described in 1958 and was introduced for medical use by 1961.[19][20][21][22] It has been marketed widely throughout the world in the past, but today its availability and usage are relatively limited.[23][6][24][25] It remains available in a few European countries and in a number of Asian countries.[23][6][24][25]

Medical uses

[edit]Allylestrenol is used in the treatment of recurrent and threatened miscarriage and to prevent premature labor.[6][7] However, except in the case of proven progesterone deficiency, its use for such indications is no longer recommended.[6] Allylestrenol is one of only a handful of progestogens that has commonly been used for such purposes, the others including progesterone, hydroxyprogesterone caproate, and dydrogesterone.[8] The medication has also been studied in the treatment of gynecological disorders such as amenorrhea, irregular menstruation, and premenstrual syndrome.[14] Unlike other progestins, allylestrenol has not been used in hormonal contraception or in menopausal hormone therapy. In one study, it was found to be inadequate for endometrial transformation in women in combination with estradiol valerate.[26] On the other hand, allylestrenol was found to be effective in the treatment of hot flashes in postmenopausal women.[27]

Allylestrenol has been commonly used in Japan at high dosages, typically 50 mg/day but as much as 100 mg/day, to treat BPH in men.[11][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][9][10][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43] Related medications that have similarly been used to treat BPH, particularly in Japan, include chlormadinone acetate, gestonorone caproate, and oxendolone.[33][38] Allylestrenol has also been studied in the treatment of prostate cancer in Japan.[44][28] The medication has been studied as a puberty blocker in the treatment of precocious puberty as well.[45]

Available forms

[edit]Allylestrenol is available in the form of 5 mg oral tablets.[12][46][47] It is typically used at a dosage of 5 to 40 mg/day.[46][47] In Japan, a 25 mg allylestrenol oral tablet, under the brand name Perselin, is marketed for the treatment of BPH.[37]

Side effects

[edit]Allylestrenol should not be taken by people who are allergic to ibuprofen or naproxen,[48] or who have salicylate intolerance[49] or a more generalized drug intolerance to NSAIDs, and caution should be exercised in those with asthma or NSAID-precipitated bronchospasm. Owing to its effect on the stomach lining, manufacturers recommend people with peptic ulcers, mild diabetes, or gastritis seek medical advice before using allylestrenol.[48]

Side effects of allylestrenol are few and have not been well-defined, but are assumed to be similar to those of related medications (i.e., other progestins).[14] When used at high dosages in the treatment of BPH in men, allylestrenol can cause symptoms of hypogonadism and sexual dysfunction.[31][34][35] The medication indeloxazine may be able to counteract allylestrenol-associated sexual dysfunction.[39] Allylestrenol has no androgenic or other off-target hormonal side effects.[31][3][16]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]

Progestogenic and off-target activities

[edit]Allylestrenol is a progestogen, or an agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR).[15] It is lacking the keto group at the C3 position (part of the important 3-keto-4-ene structure) that is common in progestogens and is considered to be necessary for activity, and in relation to this, is thought to be a prodrug of 17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone (3-ketoallylestrenol).[17][18][50] Allylestrenol is a far less potent progestogen than many other 19-nortestosterone derivatives.[15] The effective ovulation-inhibiting or contraceptive dosage of allylestrenol in women has been studied, albeit limitedly.[51] At 20 mg/day allylestrenol, ovulation occurred in 50% of 6 cycles, and at 25 mg/day, ovulation occurred in 0% of 3 cycles.[51][52] The total endometrial transformation dosage of allylestrenol in women across the cycle is 150 to 250 mg.[53] Unlike virtually all other 19-nortestosterone derivatives, allylestrenol is reported to be a pure progestogen and hence to be devoid of androgenic, estrogenic, and glucocorticoid activity.[3][16] As such, it appears to have properties more similar to those of natural progesterone.[3][16]

The binding and activity profiles of allylestrenol and its major active metabolite at steroid hormone receptors and related proteins have been studied.[3][17] Allylestrenol has less than 0.2% of the affinity of ORG-2058 and less than 2% of the affinity of progesterone for the PR.[3] Similarly, it has less than 0.2% of the affinity of testosterone for the androgen receptor (AR), less than 0.2% of the affinity of estradiol for the estrogen receptor (ER), less than 0.2% of the affinity of dexamethasone for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and 0.9% of the affinity of testosterone for sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG).[3] Conversely, its metabolite 17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone has 24% of the affinity of ORG-2058 and 186% of the affinity of progesterone for the PR, 4.5% of the affinity of testosterone for the AR, 9.8% of the affinity of dexamethasone for the GR, and 2.8% of the affinity of testosterone for SHBG, while it similarly has less than 0.2% of the affinity of estradiol for the ER.[3] The affinity of 17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone for the AR was less than that of norethisterone and medroxyprogesterone acetate and its affinity for SHBG was much lower than that of norethisterone.[3] These findings may help to explain the absence of teratogenic effects of allylestrenol on the external genitalia of female and male rat fetuses.[3]

| Compound | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allylestrenol | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | 1 | ? |

| 17α-Allyl-19-NT | 186 | 5 | 0 | 10 | ? | 3 | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were P4 for the PR, T for the AR, E2 for the ER, DEXA for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, T for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: [3] | |||||||

Antigonadotropic effects

[edit]

Similarly to other progestogens, allylestrenol has potent antigonadotropic effects.[54] It is able to considerably decrease circulating concentrations of luteinizing hormone, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone in men.[32][34][39][40] At a dosage of 50 mg/day, allylestrenol has been found to suppress circulating testosterone levels by 78% in men with BPH.[54] This is about the maximum that progestogens are known to be able to suppress testosterone levels in men.[55][56][57] In accordance, the reduction of testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels with allylestrenol in men has been found in a study to be equivalent to that of chlormadinone acetate and oxendolone.[33] However, another study found a significantly lower decrease in testosterone levels with 50 mg/day allylestrenol relative to 50 mg/day chlormadinone acetate of about 49–52% versus 76–85%, respectively.[34] Animal research suggests that allylestrenol produces its beneficial effects in BPH via its antigonadotropic effects and consequent suppression of androgen levels and inhibition of prostate gland growth, similarly to other progestins.[54] Some studies have found that allylestrenol is less effective for BPH than chlormadinone acetate but also produces fewer side effects and sexual dysfunction.[31][34][35] Allylestrenol therapy for BPH is associated with a significant decrease in prostate-specific antigen levels, which may mask the detection of prostate cancer.[54][43]

Other activities

[edit]Allylestrenol is not a significant 5α-reductase inhibitor.[54] In one study, it showed about 80,000-fold lower potency for inhibition of 5α-reductase in vitro than the established 5α-reductase inhibitor epristeride (IC50 = 11.3 nM for epristeride and 890 μM for allylestrenol).[54] In another study, there was 70% inhibition of 5α-reductase by allylestrenol at a concentration of 60 μM.[54] This difference may have been due to different experimental conditions, but is still much lower than epristeride.[54]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Following oral administration, peak levels of allylestrenol occur after 2 to 4 hours.[1][2] The medication shows considerable plasma protein binding.[1][2] It has relatively low affinity for SHBG, much lower than that of norethisterone.[3] Allylestrenol is metabolized in the liver, via reduction, hydroxylation, and conjugation.[1][2] It is known to be a substrate of CYP3A4.[5] It is thought to be a prodrug of 17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone (3-ketoallylestrenol), which, in accordance, is a known active metabolite of allylestrenol.[17][18] The biological half-life of allylestrenol has been reported to be "several hours" or, presumably in its active form, reportedly about 10 hours.[1][2][4] In the blood, unchanged allylestrenol accounted for 15 to 40% of radioactivity, an unconjugated metabolite accounted for 4 to 10% of radioactivity, and the rest of the radioactivity corresponded to conjugated metabolites.[1][2] Allylestrenol is eliminated mainly in urine, 44% by 24 hours and 67% within 4 days.[1][2] It is excreted almost completely as conjugates, with 75% of these being sulfate conjugates and 24% being glucuronide conjugates.[1][2]

Chemistry

[edit]Allylestrenol, also known as 3-deketo-17α-allyl-19-nortestosterone or as 17α-allylestr-4-en-17β-ol, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of testosterone.[58] It is a member of the estrane subgroup of the 19-nortestosterone family of progestins,[59] but unlike most other 19-nortestosterone progestins, is not a derivative of norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone).[60][3][18] This is because it possesses an allyl group at the C17α position rather than the usual ethynyl group.[60][3][18] As such, along with altrenogest (17α-allyl-19-nor-δ9,11-testosterone), allylestrenol is a derivative of 17α-allyltestosterone rather than of 17α-ethynyltestosterone.[60][3][18]

Allylestrenol is also unique among most 19-nortestosterone progestins in that it lacks the ketone at the C3 position.[58] It shares this property with lynestrenol (17α-ethynylestr-4-en-17β-ol), desogestrel (11-methylene-17α-ethynyl-18-methylestr-4-en-17β-ol), and the anabolic–androgenic steroid (AAS) ethylestrenol (17α-ethylestr-4-en-17β-ol).[58] Allylestrenol is the C17α allyl and C3 deketo derivative of the AAS nandrolone (19-nortestosterone), as well as the C17α allyl and C3 deketo analogue of the AAS normethandrone (17α-methyl-19-nortestosterone) and norethandrolone (17α-methyl-19-nortestosterone).[58]

Synthesis

[edit]Chemical syntheses of allylestrenol have been published.[58][19][61][62][63]

History

[edit]Allylestrenol was patented in 1958[19] and has been marketed for medical use since 1961.[20][21][22] It was developed by Organon Laboratories.[22][21]

Society and culture

[edit]Generic names

[edit]Allylestrenol is the generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and JAN, while allylestrénol is its DCF and allilestrenolo is its DCIT.[58][25][64][24] The BAN was originally allyloestrenol, but it was eventually changed.[58][25][24] The medication is also known by its developmental code name SC-6393.[58][25][24]

Brand names

[edit]The major brand names of allylestrenol include Gestanin, Gestanon, Perselin, and Turinal.[23][6][24][25][19] It has also been marketed under a variety of other brand names, including Alese, Alilestrenol, Allynol, Allytry, Alynol, Anin, Arandal, Astanol, Cobarenol, Crestanon, Elmolan, Fetugard, Foegard, Fulterm, Gestanin, Gestanin, Gestanol, Gestanyn, Gestin, Geston, Gestormone, Gestrenol, Gravida, Gravidin, Gravinol, Gravion, Gravynon, Gynerol, Gynonys, Iugr, Lestron, Loestrol, Maintane, Meieston, Moresafe, Nidagest, Orageston, Pelias, Preabor, Pregnolin, Pregtenol, Pregular, Prelab, Premaston, Prenolin, Prestrenol, Profar, Progeston, Protanon, and Shegest.[23][6][24][25][19]

Availability

[edit]

Allylestrenol has been marketed widely throughout the world, including in Europe, Southern, Eastern, and Southeastern Asia, Africa, Oceania, and Latin America.[23][6][24][25] However, although it has been widely marketed in the past, the availability of allylestrenol is relatively limited today.[23][6][24][25] It appears to still be available in Bangladesh, the Czech Republic, Egypt, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Lithuania, Malaysia, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, and Taiwan.[23][6][24][25] Previously, allylestrenol has also been available in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Mexico, Poland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia (now Serbia and Montenegro).[23][6][24][25] However, it seems to have been discontinued in these countries.[23][6][24][25] It does not seem to have been marketed in the United States or Canada.[23][6][24][25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bengtsson LP, Tausk M (September 1972). Pharmacology of the endocrine system and related drugs: progesterone, progestational drugs and antifertility agents. Pergamon Press. pp. 235–237. ISBN 9780080157450.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Thijssen JH (1967). Het metabolisme van progestatieve stoffen (Thesis). Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bergink EW, Loonen PB, Kloosterboer HJ (August 1985). "Receptor binding of allylestrenol, a progestagen of the 19-nortestosterone series without androgenic properties". Journal of Steroid Biochemistry. 23 (2): 165–168. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(85)90232-8. PMID 3928974.

- ^ a b Saha A, Roy K, Kakali DE (2000). "Effects of Allylestrenol on Blood Lipids in Relation to its Biological Activity". Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 62 (2): 115.

- ^ a b "SuperCYP".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Sweetman SC, ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2082. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ a b Cortés-Prieto J, Bosch AO, Rocha JA (1980). "Allylestrenol: three years of experience with Gestanon in threatened abortion and premature labor". Clinical Therapeutics. 3 (3): 200–208. PMID 7459930.

- ^ a b Haas DM, Hathaway TJ, Ramsey PS (November 2019). "Progestogen for preventing miscarriage in women with recurrent miscarriage of unclear etiology". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (11). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003511.pub5. PMC 6953238. PMID 31745982.

- ^ a b Kanimoto Y, Okada K (November 1991). "[Antiandrogen therapy of benign prostatic hyperplasia--review of the agents evaluation of the clinical results]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 37 (11): 1423–1428. PMID 1722627.

- ^ a b Umeda K (November 1991). "[Clinical results and problems of anti-androgen therapy of benign prostatic hypertrophy]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 37 (11): 1429–1433. PMID 1722628.

- ^ a b Ishizuka O, Nishizawa O, Hirao Y, Ohshima S (November 2002). "Evidence-based meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for benign prostatic hypertrophy". International Journal of Urology. 9 (11): 607–612. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00539.x. PMID 12534901.

- ^ a b Muller (19 June 1998). European Drug Index: European Drug Registrations (Fourth ed.). CRC Press. pp. 545–. ISBN 978-3-7692-2114-5.

- ^ Ganguly NK, Bano R, Seth SD (18 November 2009). "Drug Discovery and Development". In Seth SD, Seth V (eds.). Textbook Of Pharmacology. Elsevier India. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-81-312-1158-8.

- ^ a b c Borglin NE (1960). "Clinical Evaluation of the Progestational Effect of Allylestrenol". European Journal of Endocrinology. 35 (4 Suppl): NP–S15. doi:10.1530/acta.0.XXXVS0NP. ISSN 0804-4643.

- ^ a b c Field-Richards S, Snaith L (January 1961). "Allylestrenol: a new oral progestogen". Lancet. 1 (7169): 134–136. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(61)91310-1. PMID 13699366.

- ^ a b c d Madjerek Z, De Visser J, Van Der Vies J, Overbeek GA (September 1960). "Allylestrenol, a pregnancy maintaining oral gestagen". Acta Endocrinologica. 35 (I): 8–19. doi:10.1530/acta.0.XXXV0008. PMID 13765069.

- ^ a b c d McRobb L, Handelsman DJ, Kazlauskas R, Wilkinson S, McLeod MD, Heather AK (May 2008). "Structure-activity relationships of synthetic progestins in a yeast-based in vitro androgen bioassay". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 110 (1–2): 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.10.008. PMID 18395441. S2CID 5612000.

- ^ a b c d e f Zeelen FJ (1990). Medicinal chemistry of steroids. Elsevier Science Limited. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-444-88727-6.

Other examples are allylestrenol (42), a pro-drug converted to the 3-keto analogue (43), which is used in the treatment of threatened abortion [78,79] and altrenogest (44), used in sows and mares to suppress ovulation and estrus behaviour [80]. [...] Progestins with a 17a-allyl side chain: (42) allylestrenol, (43), (44) altrenogest.

- ^ a b c d e William Andrew Publishing (22 October 2013). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition. Elsevier. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-8155-1856-3.

- ^ a b Field-Richards S, Snaith L (January 1961). "Allylestrenol: a new oral progestogen". Lancet. 1 (7169): 134–136. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(61)91310-1. PMID 13699366.

- ^ a b c Simpson JA, Weiner ES (1997). Oxford English Dictionary Additions Series. Clarendon Press. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-0-19-860027-5.

1961 Lancet 21 Jan. 135/1 Allylestrenol ('Gestanin', Organon)..seems to be completely free from androgenic activity. 1962 Med. Jrnl. Austral. 8 Sept. 375/2 Each tablet of the combined hormone preparation, 'Premenquil', contains 5 mg. of allyloestrenol. [...]

- ^ a b c Medical Proceedings: A South African Journal for the Advancement of Medical Science. Juta and Company. 1962.

Just released in South Africa is Gestanin, Organon Laboratories' new safe oral progestogen. Gestanin is allylestrenol, one of a new group of steroids synthesized by Organon.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Micromedex Products: Please Login".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Allylestrenol".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Birkenfeld A, Navot D, Ezra Y, Ron A, Schenker JG (July 1987). "The effect of estradiol valerate and allylestrenol on endometrial transformation in hypergonadotropic hypogonadic women". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 25 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1016/0028-2243(87)90102-X. PMID 3609436.

- ^ Barták A, Rozprávka M, Blovský J (October 1992). "[Lynestrenol and allylestrenol in the therapy of postmenopausal hot flushes]". Ceskoslovenska Gynekologie (in Czech). 57 (8): 408–413. PMID 1473164.

- ^ a b Yamanaka H, Kosaku N, Makino T, Shida K (September 1983). "[Fundamental and clinical study of the anti-prostatic effect of allylestrenol]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 29 (9): 1133–1145. PMID 6203385.

- ^ Tajima A, Aso Y, Ushiyama T, Hata M, Kambayashi T, Ohmi Y, et al. (March 1986). "[Clinical effect of allylestrenol on benign prostatic hypertrophy]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 32 (3): 477–485. PMID 2425610.

- ^ Kohri K, Kurita T, Iguchi M, Kataoka K (March 1986). "[Clinical effects of allylestrenol on prostatic hypertrophy]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 32 (3): 486–492. PMID 2425611.

- ^ a b c d Shida K, Koyanagi T, Kawakura K, Nishida T, Kumamoto Y, Orikasa S, et al. (April 1986). "[Clinical effects of allylestrenol on benign prostatic hypertrophy by double-blind method]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 32 (4): 625–648. PMID 2426932.

- ^ a b Ohyama M, Tanifuji T, Haraguchi C, Fujii N, Higaki Y, Yoshida H, Imamura K (April 1986). "[Clinical study of allylestrenol (Org AL-25) on patients with prostatic hypertrophy--transrectal ultrasonography and urodynamic examination]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 32 (4): 649–659. PMID 2426933.

- ^ a b c Katayama T, Umeda K, Kazama T (November 1986). "[Hormonal environment and antiandrogenic treatment in benign prostatic hypertrophy]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 32 (11): 1584–1589. PMID 2435122.

- ^ a b c d e f Kumamoto Y, Yamaguchi Y, Sato Y, Suzuki R, Tanda H, Kato S, et al. (February 1990). "[Effects of anti-androgens on sexual function. Double-blind comparative studies on allylestrenol and chlormadinone acetate Part I: Nocturnal penile tumescence monitoring]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 36 (2): 213–226. PMID 1693037.

- ^ a b c Kumamoto Y, Yamaguchi Y, Sato Y, Suzuki R, Tanda H, Kato S, et al. (February 1990). "[Effects of anti-androgens on sexual function. Double-blind comparative studies on allylestrenol and chlormadinone acetate. Part II: Self-assessment questionnaire method]" (PDF). Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 36 (2): 227–244. PMID 1693038.

- ^ Tsuji Y, Ariyoshi A, Nakamura H, Michinaga S, Tomita Y, Ohmori A, et al. (August 1992). "[Antiandrogen therapy of benign prostatic hypertrophy: clinical effects of allylestrenol evaluated by transrectal ultrasonographic measurement]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 38 (8): 961–966. PMID 1384295.

- ^ a b Fukuoka H, Ishibashi Y, Shiba T, Tuchiya F, Sakanishi S (July 1993). "[Clinical study of allylestrenol (Perselin) on patients with prostatic hypertrophy]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 39 (7): 679–683. PMID 7689782.

- ^ a b Iguchi H, Ikeuchi T, Kai Y, Yoshida H (March 1994). "[Influence of anti-androgen therapy for prostatic hypertrophy on lipid metabolism]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 40 (3): 215–219. PMID 7513937.

- ^ a b c Horita H, Kumamoto Y, Satoh Y, Suzuki N, Wada H, Shibuya A, et al. (May 1995). "[The preventive effect of indeloxazine hydrochloride to the sexual dysfunction caused by anti-androgenergic agent (allylestrenol)]". Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Urology (in Japanese). 86 (5): 1044–1050. doi:10.5980/jpnjurol1989.86.1044. PMID 7541089.

- ^ a b Noguchi K, Harada M, Masuda M, Takeda M, Kinoshita Y, Fukushima S, et al. (September 1998). "Clinical significance of interruption of therapy with allylestrenol in patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy". International Journal of Urology. 5 (5): 466–470. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2042.1998.tb00389.x. PMID 9781436.

- ^ Noguchi K, Uemura H, Takeda M, Sekiguchi Y, Ogawa K, Hosaka M (September 2000). "[Rebound of prostate specific antigen after discontinuation of antiandrogen therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 46 (9): 605–607. PMID 11107528.

- ^ Noguchi K, Takeda M, Hosaka M, Kubota Y (May 2002). "[Clinical effects of allylestrenol on patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) evaluated with criteria for treatment efficacy in BPH]". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica (in Japanese). 48 (5): 269–273. PMID 12094708.

- ^ a b Noguchi K, Suzuki K, Teranishi J, Kondo K, Kishida T, Saito K, et al. (July 2006). "Recovery of serum prostate specific antigen value after interruption of antiandrogen therapy with allylestrenol for benign prostatic hyperplasia". Hinyokika Kiyo. Acta Urologica Japonica. 52 (7): 527–530. PMID 16910584.

- ^ Takeuchi H (1981). "The therapeutic effect of concurrent administration of 5-fluorouracil and allylestrenol or hexestrol in small doses on prostatic carcinoma". The Prostate. Supplement. 1: 111–117. doi:10.1002/pros.2990020518. PMID 6281750. S2CID 33940589.

- ^ Riquelme Moreno E, Montiel López P, Bravo Guerra R, Escobar Cauz G (July 1972). "[Control of 5 cases of idiopathic precocious puberty with allylestrenol]". Ginecologia y Obstetricia de Mexico (in Spanish). 32 (189): 99–108. PMID 5057420.

- ^ a b Tripathi KD (30 September 2013). Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 318–. ISBN 978-93-5025-937-5.

- ^ a b Satoskar RS, Bhandarkar SD, Rege NN (1973). "Gonadotropins, Estrogens, and Progesins". Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. Popular Prakashan. pp. 941–. ISBN 978-81-7991-527-1.

- ^ a b "Aspirin information from Drugs.com". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ Raithel M, Baenkler HW, Naegel A, Buchwald F, Schultis HW, Backhaus B, et al. (September 2005). "Significance of salicylate intolerance in diseases of the lower gastrointestinal tract". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 56 (Suppl 5): 89–102. PMID 16247191.

- ^ Rozenbaum H (March 1982). "Relationships between chemical structure and biological properties of progestogens". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 142 (6 Pt 2): 719–724. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)32477-2. PMID 7065053.

- ^ a b Endrikat J, Gerlinger C, Richard S, Rosenbaum P, Düsterberg B (December 2011). "Ovulation inhibition doses of progestins: a systematic review of the available literature and of marketed preparations worldwide". Contraception. 84 (6): 549–557. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.04.009. PMID 22078182.

- ^ Pincus G (3 September 2013). The Control of Fertility. Elsevier. pp. 222–. ISBN 978-1-4832-7088-3.

- ^ Leidenberger FA, Strowitzki T, Ortmann O (29 August 2009). Klinische Endokrinologie für Frauenärzte. Springer-Verlag. pp. 225–. ISBN 978-3-540-89760-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yasuda N, Fujino K, Shiraji T, Nambu F, Kondo K (July 1997). "Effects of steroid 5alpha-reductase inhibitor ONO-9302 and anti-androgen allylestrenol on the prostatic growth, and plasma and prostatic hormone levels in rats". Japanese Journal of Pharmacology. 74 (3): 243–252. doi:10.1254/jjp.74.243. PMID 9268084.

- ^ Jacobi GH, Altwein JE, Kurth KH, Basting R, Hohenfellner R (June 1980). "Treatment of advanced prostatic cancer with parenteral cyproterone acetate: a phase III randomised trial". British Journal of Urology. 52 (3): 208–215. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1980.tb02961.x. PMID 7000222.

- ^ Knuth UA, Hano R, Nieschlag E (November 1984). "Effect of flutamide or cyproterone acetate on pituitary and testicular hormones in normal men". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 59 (5): 963–969. doi:10.1210/jcem-59-5-963. PMID 6237116.

- ^ Sander S, Nissen-Meyer R, Aakvaag A (1978). "On gestagen treatment of advanced prostatic carcinoma". Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology. 12 (2): 119–121. doi:10.3109/00365597809179977. PMID 694436.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Elks J (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ Anita MV, Sandhya J, Jain, Goel N (31 December 2017). Use of Progestogens in Clinical Practice of Obstetrics and Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-93-5270-218-3.

- ^ a b c Aronson JK (21 February 2009). Meyler's Side Effects of Endocrine and Metabolic Drugs. Elsevier. pp. 289–. ISBN 978-0-08-093292-7.

- ^ Gunnet JW, Dixon LA (2000). "Hormones, Sex Hormones". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.19052407211414.a01. ISBN 978-0471238966.

- ^ Die Gestagene. Springer-Verlag. 27 November 2013. p. 16. ISBN 978-3-642-99941-3.

- ^ De Winter MS, Siegman CM, Szpilfogel SA (1959). "17-alkylated-3-deoxo-19-nor-testosterone". Chem. Ind.: 905.

- ^ Morton IK, Hall JM (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.