University of Birmingham

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Latin: Universitas Birminghamiensis[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto | Latin: Per Ardua ad Alta | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Motto in English | Through efforts to heights[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Public | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Established |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Endowment | £142.5 million (2023)[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Budget | £909.1 million (2022/23)[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Sandie Okoro[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | Adam Tickell | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Visitor | The Rt Hon Lucy Powell MP (as Lord President of the Council ex officio) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Academic staff | 4,260 (2022/23)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Students | 38,710 (2022/23)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 24,885 (2022/23)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 13,825 (2022/23)[8] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | , England 52°27′2″N 1°55′50″W / 52.45056°N 1.93056°W | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campus | Urban, suburban | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Colours | The University

College scarves

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Affiliations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | birmingham | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The University of Birmingham (informally Birmingham University)[9][10] is a public research university in Birmingham, England. It received its royal charter in 1900 as a successor to Queen's College, Birmingham (founded in 1825 as the Birmingham School of Medicine and Surgery), and Mason Science College (established in 1875 by Sir Josiah Mason), making it the first English civic or 'red brick' university to receive its own royal charter, and the first English unitary university.[3][11][12] It is a founding member of both the Russell Group of British research universities and the international network of research universities, Universitas 21.

The student population includes 24,885 undergraduate and 13,825 postgraduate students (2022/23), which is the 10th largest in the UK (out of 169).[8] The annual income of the university for 2022–23 was £909.1 million of which £196.7 million was from research grants and contracts, with an expenditure of £884.7 million.[5] In the 2021 Research Excellence Framework, the University of Birmingham ranked equal 13th out of 129 institutions on grade point average, up from equal 31st in the previous REF in 2014.[13]

The university is home to the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, housing works by Van Gogh, Picasso and Monet; the Shakespeare Institute; the Cadbury Research Library, the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts; the Lapworth Museum of Geology; and the 100-metre Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower, which is a prominent landmark visible from many parts of the city.[14] Academics and alumni of the university include former British Prime Ministers Neville Chamberlain and Stanley Baldwin,[15] the British composer Sir Edward Elgar and eleven Nobel laureates.[16]

History

[edit]Queen's College

[edit]

The earliest beginnings of the university were originally traced back to the Queen's College, which is linked to William Sands Cox in his aim of creating a medical school along strictly Christian lines, unlike the contemporary London medical schools.[citation needed] Further research[by whom?] revealed the roots of the Birmingham Medical School in the medical education seminars of John Tomlinson, the first surgeon to the Birmingham Workhouse Infirmary, and later to the Birmingham General Hospital. These classes, held in the winter of 1767–68, were the first such lectures ever held in England or Wales. The first clinical teaching was undertaken by medical apprentices at the General Hospital, founded in 1779. The medical school which grew out of the Birmingham Workhouse Infirmary was founded in 1828, but Cox began teaching in December 1825. Queen Victoria granted her patronage to the Clinical Hospital in Birmingham and allowed it to be styled "The Queen's Hospital". It was the first provincial teaching hospital in England. In 1843, the medical college became known as Queen's College.[17]

Mason Science College

[edit]

In 1870, Sir Josiah Mason, the Birmingham industrialist and philanthropist, who made his fortune in making key rings, pens, pen nibs and electroplating, drew up the Foundation Deed for Mason Science College.[4] The college was founded in 1875.[3] It was this institution that would eventually form the nucleus of the University of Birmingham. In 1882, the Departments of Chemistry, Botany and Physiology were transferred to Mason Science College, soon followed by the Departments of Physics and Comparative Anatomy. The transfer of the Medical School to Mason Science College gave considerable impetus to the growing importance of that college and in 1896 a move to incorporate it as a university college was made. As the result of the Mason University College Act 1897 (60 & 61 Vict. c. xx) it became incorporated as Mason University College on 1 January 1898, with Joseph Chamberlain becoming the President of its Court of Governors.

Royal charter

[edit]| Birmingham University Act 1900 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to transfer all the property and liabilities of Mason University College in the city of Birmingham to the University of Birmingham and to repeal the Mason University College Act 1897 to confer certain powers on the said University and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 63 & 64 Vict. c. xix |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 25 May 1900 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repeals/revokes | Mason University College Act 1897 |

It was largely due to Chamberlain's enthusiasm that the university was granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria on 24 March 1900.[18] The Calthorpe family offered twenty-five acres (10 hectares) of land on the Bournbrook side of their estate in July. The Court of Governors received the Birmingham University Act 1900 (63 & 64 Vict. c. xix), which put the royal charter into effect on 31 May.

The transfer of Mason University College to the new University of Birmingham, with Chamberlain as its first chancellor and Sir Oliver Lodge as the first principal, was complete. A remnant of Josiah Mason's legacy is the Mermaid from his coat-of-arms, which appears in the sinister chief of the university shield and of his college, the double-headed lion in the dexter.[19]

The commerce faculty was founded by Sir William Ashley in 1901, who from 1902 until 1923 served as first Professor of Commerce and Dean of the Faculty. From 1905 to 1908, Edward Elgar held the position of Peyton Professor of Music at the university. He was succeeded by his friend Granville Bantock.[20]

The university's own heritage archives are accessible for research through the university's Cadbury Research Library which is open to all interested researchers.[21]

During the First World War, the Great Hall in the Aston Webb Building was requisitioned by the War Office to create the 1st Southern General Hospital, a facility for the Royal Army Medical Corps to treat military casualties; it was equipped with 520 beds and treated 125,000 injured servicemen.[22]

In June 1921, the university appointed Linetta de Castelvecchio as Serena Professor of Italian: she was the first woman to hold a chair at the university and one of the first women professors in Great Britain.[23][24]

Expansion

[edit]

In 1939, the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, designed by Robert Atkinson, was opened. In 1956, the first MSc programme in Geotechnical Engineering commenced under the title of "Foundation Engineering", and has been run annually at the university since.

The UK's longest-running MSc programme in Physics and Technology of Nuclear Reactors also started at the university in 1956, the same year that the world's first commercial nuclear power station was opened at Calder Hall in Cumbria.

In 1957, Sir Hugh Casson and Neville Conder were asked by the university to prepare a masterplan on the site of the original 1900 buildings which were incomplete. The university drafted in other architects to amend the masterplan produced by the group. During the 1960s, the university constructed numerous large buildings, expanding the campus.[25] In 1963, the university helped in the establishment of the faculty of medicine at the University of Rhodesia, now the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). UZ is now independent but both institutions maintain relations through student exchange programmes.

Birmingham also supported the creation of Keele University (formerly University College of North Staffordshire) and the University of Warwick under the Vice-Chancellorship of Sir Robert Aitken who acted as 'godfather' to the University of Warwick.[26] The initial plan was to establish a satellite university college in Coventry but Aitken advised an independent initiative to the University Grants Committee.[27]

Malcolm X, the Afro-American human rights activist, addressed the University Debating Society in 1965.[22]

Scientific discoveries and inventions

[edit]

The university has been involved in many scientific breakthroughs and inventions. From 1925 until 1948, Sir Norman Haworth was Professor and Director of the Department of Chemistry. He was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Science and acted as Vice-Principal from 1947 until 1948. His research focused predominantly on carbohydrate chemistry in which he confirmed a number of structures of optically active sugars. By 1928, he had deduced and confirmed the structures of maltose, cellobiose, lactose, gentiobiose, melibiose, gentianose, raffinose, as well as the glucoside ring tautomeric structure of aldose sugars. His research helped to define the basic features of the starch, cellulose, glycogen, inulin and xylan molecules. He also contributed towards solving the problems with bacterial polysaccharides. He was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1937.[28]

The cavity magnetron was developed in the Department of Physics by Sir John Randall, Harry Boot and James Sayers. This was vital to the Allied victory in World War II. In 1940, the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, a document which demonstrated that the atomic bomb was more than simply theoretically possible, was written in the Physics Department by Sir Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch. The university also hosted early work on gaseous diffusion in the Chemistry department when it was located in the Hills building.

Physicist Sir Mark Oliphant made a proposal for the construction of a proton-synchrotron in 1943; however, he made no assertion that the machine would work. In 1945, phase stability was discovered; consequently, the proposal was revived, and construction of a machine that could surpass proton energies of 1 GeV began at the university. However, because of lack of funds, the machine did not start until 1953. The Brookhaven National Laboratory managed to beat them; they started their Cosmotron in 1952, and had it entirely working in 1953, before the University of Birmingham.[29]

In 1947, Sir Peter Medawar was appointed Mason Professor of Zoology at the university. His work involved investigating the phenomenon of tolerance and transplantation immunity. He collaborated with Rupert E. Billingham and they did research on problems of pigmentation and skin grafting in cattle. They used skin grafting to differentiate between monozygotic and dizygotic twins in cattle. Taking the earlier research of R. D. Owen into consideration, they concluded that actively acquired tolerance of homografts could be artificially reproduced. For this research, Medawar was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He left Birmingham in 1951 and joined the faculty at University College London, where he continued his research on transplantation immunity. He was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960.[30]

Recent history

[edit]

In 1999 talks commenced on the possibility of Aston University integrating itself into the University of Birmingham as the University of Birmingham, Aston Campus. This would have resulted in the University of Birmingham expanding to become one of the largest universities in the UK, with a student body of 30,000. Talks were halted in 2001 after Aston University determined the timing to be inopportune. While Aston University management was in favour of the integration, and reception among staff was generally positive, the Aston student union voted two-to-one against the integration. Despite this set back, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Birmingham said the door remained open to recommence talks when Aston University is ready.[31]

The final round of the first ever televised leaders' debates, hosted by the BBC, was held at the university during the 2010 British general election campaign on 29 April 2010.[32][33]

On 9 August 2010 the university announced that for the first time it would not enter the UCAS clearing process for 2010 admission, which matches under-subscribed courses to students who did not meet their firm or insurance choices, due to all places being taken. Largely a result of the Great Recession, Birmingham joined fellow Russell Group universities including Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Bristol in not offering any clearing places.[34]

The university acted as a training camp for the Jamaican athletics team prior to the 2012 London Olympics.[35]

A new library was opened for the 2016/17 academic year, and a new sports centre opened in May 2017.[36] The previous Main Library and the old Munrow Sports Centre, including the athletics track, have both since been demolished, with the demolition of the old library being completed in November 2017.[37]

Controversies

[edit]This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (May 2021) |

The discipline of cultural studies was founded at the university and between 1964 and 2002 the campus was home to the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, a research centre whose members' work came to be known as the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies. Despite being established by one of the key figures in the field, Richard Hoggart, and being later directed by the theorist Stuart Hall, the department was controversially closed down.[38]

Analysis showed that the university was fourth in a list of British universities that faced the most employment tribunal claims between 2008 and 2011. They were the second most likely to settle these before the hearing date.[39]

In 2011 a parliamentary early day motion was proposed, arguing against the Guild suspending the elected Sabbatical Vice President (Education), who was arrested while taking part in protest activity.[40]

In December 2011 it was announced that the university had obtained a 12-month-long injunction[41] against a group of around 25 students, who occupied a residential building on campus from 23 to 26 November 2011, preventing them from engaging in further "occupational protest action" on the university's grounds without prior permission. It was misreported in the press that this injunction applied to all students; however, the court order defines the defendants as:

Persons unknown (including students of the University of Birmingham) entering or remaining upon the buildings known as No. 2 Lodge Pritchatts Road, Birmingham at the University of Birmingham for the purpose of protest action (without the consent of the University of Birmingham).[42]

The university and the Guild of Students also clarified the scope of the injunction in an e-mail sent to all students on 11 January 2012, stating: "The injunction applies only to those individuals who occupied the lodge".[43] The university said that it sought this injunction as a safety precaution based on a previous occupation.[44] Three separate human rights groups, including Amnesty International, condemned the move as restrictive on human rights.[45]

In 2019, several women said the university refused to investigate allegations of campus rape. One student who complained of rape in university accommodation was told by employees of the university that there were no specific procedures for handling rape complaints. In other cases students were told they would have to prove the alleged rapes occurred on university property. The university has been criticized by legal professionals for not adequately assessing the risk to students by refusing to investigate complaints of criminal conduct.[46]

In June 2022 the University published a report into, and apologised for, its involvement in developing, promoting and administering electric-shock conversion therapy to gay men, during the period 1966-1983.[47][48]

Campuses

[edit]Edgbaston campus

[edit]Original buildings

[edit]

The main campus of the university occupies a site some 3 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Birmingham city centre, in Edgbaston. It is arranged around Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower (affectionately known as 'Old Joe' or 'Big Joe'), a grand campanile which commemorates the university's first chancellor, Joseph Chamberlain.[49] Chamberlain may be considered the founder of Birmingham University, and was largely responsible for the university gaining its Royal Charter in 1900 and for the development of the Edgbaston campus. The university's Great Hall is located in the domed Aston Webb Building, which is named after one of the architects – the other was Ingress Bell. The initial 25-acre (100,000 m2) site was given to the university in 1900 by Lord Calthorpe. The grand buildings were an outcome of the £50,000 given by steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to establish a "first class modern scientific college"[50] on the model of Cornell University in the United States.[51] Funding was also provided by Sir Charles Holcroft.[52]

The original domed buildings, built in Accrington red brick, semicircle to form Chancellor's Court. This sits on a 30 feet (9.1 m) drop, so the architects placed their buildings on two tiers with a 16 feet (4.9 m) drop between them. The clock tower stands in the centre of the Court.

The campanile itself draws its inspiration from the Torre del Mangia, a medieval clock tower that forms part of the Town Hall in Siena, Italy.[53] When it was built, it was described as 'the intellectual beacon of the Midlands' by the Birmingham Post. The clock tower was Birmingham's tallest building from the date of its construction in 1908 until 1969; it is now the third highest in the city. It is one of the top 50 tallest buildings in the UK,[54] and the tallest free-standing clock tower in the world,[14] although there is some confusion about its actual height, with the university listing it both as 110 metres (361 ft)[55] and 325 feet (99 m) tall in different sources.[56]

The campus has a wide diversity in architectural types and architects. "What makes Birmingham so exceptional among the Red Brick universities is the deployment of so many other major Modernist practices: only Oxford and Cambridge boast greater selections".[57] The Guild of Students original section was designed by Birmingham inter-war architect Holland Hobbiss who also designed the King Edward's School opposite. It was described as "Redbrick Tudorish" by Nikolaus Pevsner.[58]

The statue on horseback fronting the entrance to the university and Barber Institute of Fine Arts is a 1722 statue of George I rescued from Dublin in 1937. This was saved by Bodkin, a director of the National Gallery of Ireland and first director of the Barber Institute. The statue was commissioned by the Dublin Corporation from the Flemish sculptor John van Nost.[59]

Final negotiations for part of what is now the Vale were only completed in March 1947. By then, properties which would have their names used for halls of residences such as Wyddrington and Maple Bank were under discussion and more land was obtained from the Calthorpe estate in 1948 and 1949 providing the setting for the Vale.[60] Landscape architect Mary Mitchell designed the layout of the campus and she included mature trees that were retained from the former gardens.[61] Construction on the Vale started in 1962 with the creation of a 3-acre (12,000 m2) artificial lake and the building of Ridge, High, Wyddrington and Lake Halls. The first, Ridge Hall, opened for 139 women in January 1964, with its counterpart High Hall admitting its first male residents the following October.[62]

1960s and modern expansion

[edit]

The university underwent a major expansion in the 1960s due to the production of a masterplan by Casson, Conder and Partners. The first of the major buildings to be constructed to a design by the firm was the Refectory and Staff House which was built in 1961 and 1962. The two buildings are connected by a bridge. The next major buildings to be constructed were the Wyddrington and Lake Halls and the Faculty of Commerce and Social Science, all completed in 1965. The Wyddrington and Lake Halls, on Edgbaston Park Road, were designed by H. T. Cadbury-Brown and contained three floors of student dwellings above a single floor of communal facilities.[citation needed]

The Faculty of Commerce and Social Science, now known as the Ashley Building, was designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis and is a long, curving two-storey block linked to a five-storey whorl. The two-storey block follows the curve of the road, and has load-bearing brick cross walls. It is faced in specially-made concrete blocks. The spiral is faced with faceted pre-cast concrete cladding panels.[25] It was statutorily listed in 1993[63] and a refurbishment by Berman Guedes Stretton was completed in 2006.[64]

Chamberlain, Powell and Bon were commissioned to design the Physical Education Centre which was built in 1966. The main characteristic of the building is the roof of the changing rooms and small gymnasium which has hyperbolic paraboloid roof light shells and is completely paved in quarry tiles. The roof of the sports hall consists of eight conoidal 2½-inch thick sprayed concrete shells springing from 80-foot (24 m) long pre-stressed valley beams. On the south elevation, the roof is supported on raking pre-cast columns and reversed shells form a cantilevered canopy.[citation needed]

Also completed in 1966 was the Mining and Minerals Engineering and Physical Metallurgy Departments, which was designed by Philip Dowson of Arup Associates. This complex consisted of four similar three-storey blocks linked at the corners. The frame is of pre-cast reinforced concrete with columns in groups of four and the whole is planned as a tartan grid, allowing services to be carried vertically and horizontally so that at no point in a room are services more than ten feet away. The building received the 1966 RIBA Architecture Award for the West Midlands.[25] It was statutorily listed in 1993.[63] Taking the full five years from 1962 to 1967, Birmingham erected twelve buildings which each cost in excess of a quarter of a million pounds.[65]

In 1967, Lucas House, a new hall of residence designed by The John Madin Design Group, was completed, providing 150 study bedrooms. It was constructed in the garden of a large house. The Medical School was extended in 1967 to a design by Leonard J. Multon and Partners. The two-storey building was part of a complex which covers the southside of Metchley Fort, a Roman fort. In 1968, the Institute for Education in the Department for Education was opened. This was another Casson, Conder and Partners-designed building. The complex consisted of a group of buildings centred around an eight-storey block, containing study offices, laboratories and teaching rooms. The building has a reinforced concrete frame which is exposed internally and the external walls are of silver-grey rustic bricks. The roofs of the lecture halls, penthouse and Child Study wing are covered in copper.[25]

Arup Associates returned in the 1960s to design the Arts and Commerce Building, better known as Muirhead Tower and houses the Institute of Local Government Studies. This was completed in 1969.[25] A£42 million refurbishment of the 16-storey tower was completed in 2009 and it now houses the Colleges of Social Sciences and the Cadbury Research Library, the new home for the university's Special Collections. The podium was remodeled around the existing Allardyce Nicol studio theatre, providing additional rehearsal spaces and changing and technical facilities. The ground floor lobby now incorporates a Starbucks coffee shop.[66] The name, Muirhead Tower, came from that of the first philosophy professor of the university John Henry Muirhead.[66][67][68]

Recently[when?] completed is a 450-seat concert hall, called the Bramall Music Building, which completes the redbrick semicircle of the Aston Webb building designed by Glenn Howells Architects with venue design by Acoustic Dimensions. This auditorium, with its associated research, teaching and rehearsal facilities, houses the Department of Music.[69] In August 2011 the university announced that architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands and S&P were appointed to develop a new Indoor Sports Centre as part of a £175 million investment in the campus.[needs update][70]

Other features

[edit]

In 1978, University station, on the Cross-City Line, was opened to serve the university and its hospital. It is the only university campus in mainland Britain with its own railway station.[citation needed] In 2021, construction began on a redeveloped facility adjacent to the existing structure as part of the West Midlands Rail Programme (WMRP).[71] The rebuilt station was completed and opened to the public in January 2024.[72] Nearby, the Steampipe Bridge, which was constructed in 2011, transports steam across the Cross-City Railway Line and Worcester & Birmingham Canal from the energy generation plant to the medical school as part of the university's sustainable energy strategy. Its laser-cut exterior is also a public art feature.[73]

Located within the Edgbaston site of the university is the Winterbourne Botanic Garden, a 24,000 square metre (258,000 square foot) Edwardian Arts and Crafts style garden. The large statue in the foreground was a gift to the university by its sculptor Sir Edward Paolozzi – the sculpture is named 'Faraday', and has an excerpt from the poem 'The Dry Salvages' by T. S. Eliot around its base.

The University of Birmingham operates the Lapworth Museum of Geology in the Aston Webb Building in Edgbaston. It is named after Charles Lapworth, a geologist who worked at Mason Science College.

Since November 2007, the university has been holding a farmers' market on the campus.[74] Birmingham is the first university in the country to have an accredited farmers' market.[75]

The considerable extent of the estate meant that by the end of the 1990s it was valued at £536 million.[76]

University of Birmingham marked its grand ending of Green Heart Project at the start of 2019.[77][78]

In 2021, the University opened a central-city meeting and conference site called The Exchange in the former Birmingham Municipal Bank in Centenary Square.[79]

Selly Oak campus

[edit]The university's Selly Oak campus is a short distance to the south of the main campus. It was the home of a federation of nine colleges, known as Selly Oak Colleges, mainly focused on theology, social work, and teacher training.[80] The Federation was for many years associated with the University of Birmingham. A new library, the Orchard Learning Resource Centre, was opened in 2001, shortly before the Federation ceased to exist. The OLRC is now one of Birmingham University's site libraries.[81] Among the Selly Oak Colleges was Westhill College, (later the University of Birmingham, Westhill), which merged with the university's School of Education in 2001.[82] In the following years most of the remaining colleges closed, leaving two colleges which continue today, Woodbrooke College, a study and conference centre for the Society of Friends, and Fircroft College, a small adult education college with residential provision. Woodbrooke College's Centre for Postgraduate Quaker Studies, established in 1998, works with the University of Birmingham to deliver research supervision for the degrees of MA by research and PhD.[83]

The Selly Oak campus is now home to the Department of Drama and Theatre Arts in the newly refurbished Selly Oak Colleges Old Library and George Cadbury Hall 200-seat theatre.[84] The UK daytime television show Doctors is filmed on this campus.[85] The University of Birmingham School occupies a brand new, purpose-built building located on the university's Selly Oak campus.[86] The University of Birmingham School is sponsored by the University of Birmingham and managed by an Academy Trust. The University of Birmingham School opened in September 2015.[87]

Mason College and Queen's College campus

[edit]

The Victorian neo-gothic Mason College Building in Birmingham city centre housed Birmingham University's Faculties of Arts and Law for over 50 years after the founding of the university in 1900. The Faculty of Arts building on the Edgbaston campus was not constructed until 1959–61. The Faculties of Arts and Law then moved to the Edgbaston campus.[88] The original Mason College Building was demolished in 1962 as part of the redevelopment within the inner ring road.

The 1843 Gothic Revival building constructed opposite the Town Hall between Paradise Street (the main entrance) and Swallow Street served as Queen's College, one of the founder colleges of the university. In 1904 the building was given a new buff-coloured terracotta and brick front. The medical and scientific departments merged with Mason College in 1900 to form the University of Birmingham and sought new premises in Edgbaston. The theological department of Queen's College did not merge with Mason College, but later moved in 1923 to Somerset Road in Edgbaston, next to the University of Birmingham as the Queen's Foundation, maintaining a relationship with the University of Birmingham until a 2010 review. In the mid 1970s, the original Queen's College building was demolished, with the exception of the grade II listed façade.

Dubai Campus

[edit]The university also has an affiliated Dubai campus established in 2017 at Dubai International Academic City (DIAC). They have since moved from the DIAC headquarters with the construction of a new campus in 2022 in the same area, inaugurated by the Dubai crown prince Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum. The campus boasts of having all faculty flown in or permanently staffed from the UK campus.[89]

Organisation and administration

[edit]Academic departments

[edit]

Birmingham has departments covering a wide range of subjects. On 1 August 2008, the university's system was restructured into five 'colleges', which are composed of numerous 'schools':

- Arts and Law (English, Drama and Creative Studies; History and Cultures; Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music; Birmingham Law School; Philosophy, Theology and Religion)

- Engineering and Physical Sciences (Chemistry; Chemical Engineering; Computer Science; Engineering (comprising the Departments of civil, Mechanical and Electrical, Electronic & Systems Engineering); Mathematics; Metallurgy and Materials; Physics and Astronomy)

- Life and Environmental Sciences (Biosciences; Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences; Psychology; Sport and Exercise Sciences)

- Medical and Dental Sciences (Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences; Institute of Clinical Sciences; Institute of Inflammation and Ageing; Institute of Applied Health Research; Institute of Cardiovascular Science; Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy; Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research; Institute of Microbiology and Infection).

- Social Sciences (Birmingham Business School; Education; Government and Society; Social Policy)

- Liberal Arts and Sciences

The university is home to a number of research centres and schools, including the Birmingham Business School, the oldest business school in England, the University of Birmingham Medical School, the International Development Department, the Institute of Local Government Studies, the Centre of West African Studies, the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, the Centre of Excellence for Research in Computational Intelligence and Applications and the Shakespeare Institute. The Third Sector Research Centre was established in 2008,[90] and the Institute for Research into Superdiversity was established in 2013.[91] Apart from traditional research and PhDs, under the department of Engineering and Physical Sciences, the university offers split-site PhD in Computer Science.[92] The university is also home to the Birmingham Solar Oscillations Network (BiSON) which consists of a network of six remote solar observatories monitoring low-degree solar oscillation modes. It is operated by the High Resolution Optical Spectroscopy group of the School of Physics and Astronomy, funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).[93]

International Development Department

[edit]The International Development Department (IDD) is a multi-disciplinary academic department focused on poverty reduction through developing effective governance systems. The department is one of the leading UK centres for the postgraduate study of international development.[94] The department has been described as being a "highly regarded, long-established specialist unit" with a "global reputation" by The Independent.[95]

Off-campus establishments

[edit]

A number of the university's centres, schools and institutes are located away from its two campuses in Edgbaston and Selly Oak:

- The Shakespeare Institute, in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is a centre for postgraduate study dedicated to the study of William Shakespeare and the literature of the English Renaissance.

- The Ironbridge Institute, in Ironbridge, which offers postgraduate and professional development courses in heritage.

- The School of Dentistry (the UK's oldest dental school), in Birmingham City Centre.

- The Raymond Priestley Centre, near Coniston in the Lake District, which is used for outdoor pursuits and field work.[96]

There is also a Masonic Lodge that has been associated with the university since 1938.[97]

University of Birmingham Observatory

[edit]

In the early 1980s, the University of Birmingham constructed an observatory next to the university playing fields, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Edgbaston campus. The site was chosen because the night sky was ~100 times darker than the skies above campus. First light was on 8 December 1982, and the Observatory was officially opened by the Astronomer Royal, Francis Graham-Smith, on 13 June 1984.[98] The observatory was upgraded in 2013.

The Observatory is used primarily for undergraduate teaching.[99] It has two main instruments, a 16" Cassegrain (working at f/19) and a 14" Meade LX200R (working at f/6.35). A third telescope is also present and is used exclusively for visual observations.

Members of the public are given chance to visit the Observatory at regular Astronomy in the City events during the winter months.[100] These events include a talk on the night sky from a member of the university's student Astronomical Society; a talk on current astrophysics research, such as exoplanets, galaxy clusters or gravitational-wave astronomy,[101] a question-and-answer session, and the chance to observing using telescopes both on campus and at the Observatory.

Branding

[edit]The original coat of arms was designed in 1900. It features a double headed lion (on the left) and a mermaid holding a mirror and comb (to the right). These symbols owe to the coat of arms of the institution's predecessor, Mason College.

In 2005 the university began rebranding itself. A simplified edition of the shield which had been introduced in the 1980s reverted to a detailed version based on how it appears on the university's original Royal Charter.

Academic profile

[edit]Libraries and collections

[edit]

Library Services operates six libraries. They are the Barber Fine Art Library, Barnes Library, Main Library, Orchard Learning Resource Centre, Dental Library, and the Shakespeare Institute Library. Library Services also operates the Cadbury Research Library.[102]

The Shakespeare Institute's library is a major United Kingdom resource for the study of English Renaissance literature.[103]

The Cadbury Research Library is home to the University of Birmingham's historic collections of rare books, manuscripts, archives, photographs and associated artefacts. The collections, which have been built up over a period of 120 years consist of over 200,000 rare printed books including significant incunabula, as well as over 4 million unique archive and manuscript collections.[104] The Cadbury Research Library is responsible for directly supporting the university's research, learning and teaching agenda, along with supporting the national and international research community.

The Cadbury Research Library contains the Chamberlain collection of papers from Neville Chamberlain, Joseph Chamberlain and Austen Chamberlain, the Avon Papers belonging to Anthony Eden with material on the Suez Crisis, the Cadbury Papers relating to the Cadbury firm from 1900 to 1960, the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern Manuscripts of Alphonse Mingana, the Noël Coward Collection, the papers of Edward Elgar, Oswald Mosley, and David Lodge, and the records of the English YMCA and of the Church Missionary Society. The Cadbury Research Library has recently taken in the complete archive of UK Save the Children. The Library holds important first editions such as De Humani Corporis (1543) by Versalius, the Complete Works (1616) of Ben Jonson, two copies of The Temple of Flora (1799-1807) by Robert Thornton and comprehensive collections of the works of Joseph Priestley and D H Lawrence as well as many other significant works.

In 2015, a Quranic manuscript in the Mingana Collection was identified as one of the oldest to have survived, having been written between 568 and 645.[105][106]

At the beginning of the 2016/17 academic year, a new main library opened on the Edgbaston campus and the old library has now been demolished as part of the plans to create a 'Green Heart' as per the original plans for the university whereby the clock tower would be visible from the North Gate.[107][108] The Harding Law Library was closed and renovated to become the university's Translation and Interpreting Suite.

Medicine

[edit]

The University of Birmingham's medical school is one of the largest in Europe with well over 450 medical students being trained in each of the clinical years and over 1,000 teaching, research, technical and administrative staff [citation needed]. The school has centres of excellence in cancer, pharmacy, immunology, cardiovascular disease, neuroscience and endocrinology, and is renowned nationally and internationally for its research and developments in these fields.[109][better source needed] The medical school has close links with the NHS and works closely with 15 teaching hospitals and 50 primary care training practices in the West Midlands.

The University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust is the main teaching hospital in the West Midlands. It has been given three stars for the past four consecutive years.[110]

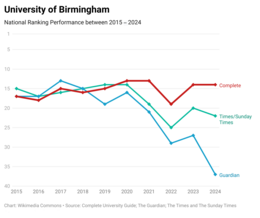

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[111] | 12= |

| Guardian (2025)[112] | 36 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2025)[113] | 22 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2024)[114] | 151–200 |

| QS (2025)[115] | 80= |

| THE (2025)[116] | 93= |

The 2022 U.S. News & World Report ranks Birmingham 91st in the world.[117] In 2019, it is ranked 137th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[118]

In 2021 the Times Higher Education placed Birmingham 12th in the UK.[119]

In 2013, Birmingham was named 'Sunday Times University of the Year 2014'.[120] The 2013 QS World University Rankings placed Birmingham University at 10th in the UK and 62nd internationally. Birmingham was ranked 12th in the UK in the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise with 16 per cent of the university's research regarded as world-leading and 41 per cent as internationally excellent, with particular strengths in the fields of music, physics, biosciences, computer science, mechanical engineering, political science, international relations and law.[121][122][123] Course satisfaction was at 85% in 2011 which grew to 88% in 2012.[124]

In 2015 the Complete University Guide placed Birmingham 5th in the UK for graduate prospects.[125]

Data from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) placed the university amongst the twelve elite institutions who among them take more than half of the students with the highest A-level grades.[126]

Birmingham traditionally had a focus on science, engineering, commerce and coal mining, but has now expanded its provision. It hosted the first Cancer Research UK Centre,[127] and making notable contributions to gravitational-wave astronomy, hosting the Institute of Gravitational Wave Astronomy.[128]

The School of Computer Science ranked 1st in the 2014 Guardian University Guide,[129] 4th in the 2013 Sunday Times League Table and 6th in the 2014 Sunday Times League Table.[130]

The Department of Philosophy ranked 3rd in the 2017 Guardian University League Tables,[131] below the University of Oxford and above the University of Cambridge, with the first being the University of St Andrews.

The combined course of Computer Science and Information Systems, titled Computer Systems Engineering was ranked 4th in the 2016 Guardian University guide.[132]

The Department of Political Science and International Studies (POLSIS) ranked 4th in the UK and 22nd in the world in the Hix rankings of political science departments.[133] The sociology department also ranked 4th by The Guardian University guide. The Research Fortnight's University Power Ranking, based on quality and quantity of research activity, put the University of Birmingham 12th in the UK, leading the way across a broad range of disciplines including Primary Care, Cancer Studies, Psychology and Sport and Exercise Sciences.[134] The School of Physics and Astronomy also performed well in the rankings, being ranked 3rd in the 2012 Guardian University Guide[135] and 7th in The Complete University Guide 2012.[136] The School of Chemical Engineering is ranked second in the UK by the 2014 Guardian University Guide.[137]

Admissions

[edit]

|

| Domicile[141] and Ethnicity[142] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British White | 48% | ||

| British Ethnic Minorities[a] | 27% | ||

| International EU | 3% | ||

| International Non-EU | 22% | ||

| Undergraduate Widening Participation Indicators[143][144] | |||

| Female | 57% | ||

| Private School | 16% | ||

| Low Participation Areas[b] | 8% | ||

In terms of the average UCAS points of entrants, Birmingham ranked 26th in Britain in 2021.[140] According to the 2017 Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide, approximately 20% of Birmingham's undergraduates come from independent schools.[145] In 2016, the university gave offers of admission to 79.2% of applicants, the 8th highest amongst the Russell Group.[146] In 2022, offers were given to 61.3% of undergraduate applicants, the 30th lowest offer rate across the country.[147]

In the 2016–17 academic year, the university had a domicile breakdown of 76:5:18 of UK:EU:non-EU students respectively, with a female to male ratio of 56:44.[148] 50.3% of international students enrolled at the institution are from China, the fourth highest proportion out of all mainstream universities in the UK.[149]

Birmingham Heroes

[edit]To highlight leading areas of research, the university has launched the Birmingham Heroes scheme. Academics who lead research that impacts on the lives of people regionally, nationally and globally can be nominated for selection.[150] Heroes include:

- Alberto Vecchio and Andreas Freise for their work as part of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration towards the first observation of gravitational waves[151]

- Martin Freer, Toby Peters and Yulong Ding for their work on energy efficient cooling[152]

- Philip Newsome, Thomas Solomon and Patricia Lalor for tackling the silent killers, liver disease and diabetes[153]

- James Arthur, Kristján Kristjánsson, Sandra Cooke and Tom Harrison for promoting character in education[154]

- Lisa Bortolotti, Ema Sullivan-Bissett and Michael Larkin for their work on how to break down the stigma associated with mental illness[155]

- Kate Thomas, Joe Alderman, Rima Dhillon and Shayan Ahmed for their research in and teaching of life sciences[156]

- Pam Kearns, Charlie Craddock and Paul Moss for cancer research[157]

- Anna Phillips, Glyn Humphreys and Janet Lord who research healthy ageing[158]

- Pierre Purseigle, Peter Gray and Bob Stone for using their historical knowledge to advise government organisations[159]

- Paul Bowen and Nick Green for research into new materials to improve energy generation[160]

- Lynne Macaskie, William Bloss and Jamie Lead for their study of pollutants, particularly nanoscale pollutants[161]

- Paul Jackson, Scott Lucas and Stefan Wolff for their work helping with post-conflict and advice on the application of aid[162]

- Hongming Xu, Clive Roberts and Roger Reed for work on sustainable transport[163]

- Moataz Attallah, Kiran Trehan and Tim Daffron for driving economic growth through improving aerospace engineering, developing enterprise and pioneering industrial applications of synthetic biology[164]

Birmingham Fellows

[edit]

The Birmingham Fellowship scheme was launched in 2011. The scheme encourages high potential early career researchers to establish themselves as rounded academics and continue pursuing their research interests. This scheme was the first of its kind, and has since been emulated in several other Russell Group universities across the UK.[165] Since 2014, the scheme has been divided into Birmingham Research Fellowships and Birmingham Teaching Fellowships. Birmingham Fellows are appointed to permanent academic posts (with two or three year probation periods), with five years protected time to develop their research.[166]

Birmingham Fellows are usually recruited at a lecturer or senior lecturer level. In the first period of the fellowship, emphasis is placed on the research aspect, publishing high quality academic outputs, developing a trajectory for their work and gaining external funding. However, development of teaching skills is encouraged.[166] Teaching and supervisory responsibilities, as well as administrative duties, then steadily increase to a normal lecturer's load in the Fellow's respective discipline by the fifth year of the fellowship. Birmingham Fellows are not expected to carry out academic administration during their term as Fellows, but will do once their posts turn into lectureships ('three-legged contract'). When accepted into the Birmingham Research Fellowship, Fellows receive a start-up package to develop or continue their research projects, an academic mentor and support for both research and teaching. All fellows are said to become part of the Birmingham Fellows Cohort, which provides them a university-wide network and an additional source of support and mentoring.[166]

International cooperation

[edit]In Germany the University of Birmingham cooperates with the Goethe University Frankfurt. Both cities are linked by a long-lasting partnership agreement.

Student life

[edit]Guild of Students

[edit]

The University of Birmingham Guild of Students is the university's student union. Originally the Guild of Undergraduates, the institution had its first foundations in the Mason Science College in the centre of Birmingham around 1876. The University of Birmingham itself formally received its Royal Charter in 1900 with the Guild of Students being provided for as a Student Representative Council.[167] It is not known for certain why the name 'Guild of Students' was chosen as opposed to 'Union of Students'; however, the Guild shares its name with Liverpool Guild of Students, another 'redbrick university'; both organisations subsequently founded the National Union of Students. The Union Building, the Guild's bricks and mortar presence, was designed by the architect Holland W. Hobbiss.

The Guild's official purposes are to represent its members and provide a means of socialising, though societies and general amenities. The university provides the Guild with the Union Building effectively rent free as well as a block grant to support student services. The Guild also runs several bars, eateries, social spaces and social events.

The Guild supports a variety of student societies and volunteering projects, roughly around 220 at any one time. The Guild complements these societies and volunteering projects with professional staffed services, including its walk-in Advice and Representation Centre (ARC), Student Activities, Jobs/Skills/Volunteering, Student Mentors in halls, and Community Wardens around Bournbrook.[168] The Guild of Students was where the student volunteering charity InterVol was conceived and developed as a student-led volunteering project in the early 2000s; the project links students will local volunteering opportunities as well as placements with charitable partners overseas.[169][170] Another two of the Guild's long-standing societies are Student Advice and Nightline (previously Niteline), which both provide peer-to-peer welfare support. The Guild was one of the first universities in the United Kingdom to publish a campus newspaper, Redbrick, supported financially by the Guild of Students and advertising revenue.[171]

The Guild undertakes its representative function through its officer group, seven of whom are full-time, on sabbatical from their studies, and ten of whom are part-time and hold their positions whilst still studying. Elections are held yearly, conventionally February, for the following academic year. These officers have regular contact with the university's officer-holders and managers. In theory, the Guild's officers are directed and kept to account over their year in office by Guild Council, an 80-seat decision-making body. The Guild also supports the university "student reps" scheme, which aims to provide an effective channel of feedback from students on more of a departmental level.

Sport

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2021) |

This section contains promotional content. (March 2021) |

The University of Birmingham opened the Sport and Fitness Centre in May 2017 providing facilities including gym, squash courts, 50 m swimming pool, and climbing wall. The University has two international standard hockey pitches, completed in 2017,[172] flexible 3G pitches which can be used for 5-a-side and 11-a-side football, as well as netball and tennis courts, and a 400m athletics track at Edgbaston Park Road.[173]

As of the 2019 league, the university is ranked seventh in the British Universities and Colleges Sport league table.[174]

University of Birmingham Sport provides a range of competitive and participation sports, for both the student and local community. Services include 180 fitness classes a week, 56 different sport clubs, including rowing, basketball, cricket, football, rugby union, netball, field hockey, ice hockey, American football, and triathlon. The wide selection has ensured the university has over 4,000 students participating in sport each year. The university also opened the Raymond Priestley Centre in 1981 on the shores of Coniston Water in the Lake District, offering students, staff and community alike to explore outdoor activities and learning in the area.

Sir Raymond Priestley, vice-chancellor of the university in 1938, and his Director of Sport A.D. Munrow, helped establish the first undergraduate courses in Physical Education in 1946, developed their sports facilities – starting with the gymnasium in 1939, and made participation in recreational sport compulsory for all new undergraduates from 1940 to 1968. Birmingham became the first UK university to offer a sports degree.

Students and alumni from the University of Birmingham have competed at Olympics, Paralympics and Commonwealth Games. In 2004, six graduates and one student competed in the 2004 Athens Summer Olympics, and four alumni competed at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, including cyclist Paul Manning who won an Olympic Gold.[175] In 2012, Pamela Relph MBE was part of the rowing mixed coxed four that won Paralympic gold, and she successfully defended her title in Rio: the only current international para-rower to be a double Paralympic Champion.

In the 2018 Commonwealth Games in Gold Coast, Australia, six students and eighteen alumni attended representing England, Scotland, Wales, and Guernsey, and competing in sports including hockey, 1500m, badminton, and cycling.[176]

The university hosted the Jamaican track and field team prior to the 2012 London Olympics. The team, including the world's fastest man, Usain Bolt – who became the first man in history to defend his 100 metres and 200 metres titles at the Olympics – won team gold for the 4 × 400 m along with Nesta Carter, Yohan Blake and Michael Frater. Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce won gold in the women's 100 metres. The team returned to the university in 2017 to prepare for London's Indoor Championships, staying in the Chamberlain Hall on the Vale Village, and using the newly established Sport & Fitness facilities and athletics track.

University of Birmingham Sport has since been host to a number of international teams; the Australian and South Africa teams ahead of the men's Rugby World Cup in 2015, the Jamaican, England and New Zealand netball teams before the Vitality Nations Cup in January 2020, and 19 nations for the individual competition at the World University Squash Championships in 2018.

Birmingham was selected as the host for the 2022 Commonwealth Games and the University was chosen as the venue for hockey and squash, due to the ability of existing facilities to host the games with only temporary structures needing to be constructed for seating, lighting, and broadcasting. The University was the largest athletes village during the games, hosting 3,500 athletes in Tennis Courts and the Vale, and the University was the official training venue for both swimming and athletics.[177]

University of Birmingham Sport also offers around 30 scholarships and bursaries to national and international students of exceptional athletic ability.[178]

Housing

[edit]The university provides housing for most first-year students, running a guarantee scheme for all those UK applicants who choose Birmingham as their firm UCAS choice. 90 per cent of university-provided housing is inhabited by first-year students.[179]

The university maintained gender-segregated halls until the beginning of the 1998-99 academic year when Lake and Wyddrington "halls" (treated as two different halls, despite being physically one building) were renamed as Shackleton Hall. Chamberlain Hall (Eden Tower), a seventeen-storey tower block, was originally known as High Hall, for male students, and the connected Ridge Hall (later renamed to the Hampton Wing), for female students. University House was decommissioned as accommodation to house the expanding Business School, while Mason Hall has been demolished and rebuilt, opening in 2008.[citation needed] In the summer of 2006, the university sold three of its most distant halls (Hunter Court, the Beeches and Queens Hospital Close) to private operators, while later in the year and during term, the university was forced urgently to decommission both the old Chamberlain Tower (High Hall) and also Manor House over fire safety inspection failures.[citation needed] The university has rebranded its halls offerings into three villages.[citation needed]

Vale Village

[edit]

The Vale Village includes Chamberlain Hall, Shackleton, Maple Bank, Tennis Court, Elgar Court and Aitken residences. A sixth hall of residence, Mason Hall, re-opened in September 2008 following a complete rebuild. Approximately 2,700 students live in the village.[180]

Shackleton Hall (originally Lake Hall, for male students, and Wyddrington Hall, for female students) underwent an £11 million refurbishment and was re-opened in Autumn 2004. There are 72 flats housing a total of 350 students. The majority of the units consist of six to eight bedrooms, together with a small number of one, two, three or five bedroom studio/apartments.[181] The redevelopment was designed by Birmingham-based architect Patrick Nicholls while employed at Aedas, now a director of Glancy Nicholls Architects.[182]

Maple Bank was refurbished and opened in summer 2005. It consists of 87 five bedroom flats, housing 435 undergraduates.[183]

The Elgar Court residence consists of 40 six bedroom flats, housing a total of 236 students.[184] It opened in September 2003.

Tennis Court consists of 138 three, four, five and six bedroom flats and houses 697 students.[185]

The Aitken wing is a small complex consisting of 23 six and eight bedroom flats. It houses 147 students.[186]

Construction of the new Mason Hall commenced in June 2006 following complete demolition of the original 1960s structures. It was designed by Aedas Architects. The entire project is thought to have cost £36.75 million.[187] It has since been completed, with the first year of students moving in September 2008.

The new Chamberlain Tower and neighbouring low rise blocks opened in September 2015. Chamberlain is home to more than 700 first year students. It replaced the old 1964-built 18-storey (above ground level) High Hall (later renamed Eden Tower), for male students and low rise Ridge Hall (later renamed Hampton Wing) for female students, which closed in 2006. The 50-year-old Eden Tower was removed at the start of 2014. Previously known as High Hall, the tower and its associated low rise blocks were demolished after studies revealed it would be uneconomical to refurbish them and would not provide the quality of accommodation which the University of Birmingham desires for students.

The largest student-run event, the Vale Festival or 'ValeFest', is held annually on the Vale. The Festival celebrated its 10th event in 2014, raising £25,000 for charity. The 2019 event was headlined by The Hunna and Saint Raymond.

Pritchatts Park Village

[edit]

The Pritchatts Park Village houses over 700 undergraduate and postgraduate students. Halls include 'Ashcroft', 'The Spinney' and 'Oakley Court', as well as 'Pritchatts House' and the 'Pritchatts Road Houses'.[188]

The Spinney is a small complex of six houses and twelve smaller flats, housing 104 students in total.[189] Ashcroft consists of four purpose built blocks of flats and houses 198 students.[190] The four-storey Pritchatts House consists of 24 duplex units and houses 159 students.[191] Oakley Court consists of 21 individual purpose-built flats, ranging in size from five to thirteen bedrooms. Also included are 36 duplex units. A total of 213 students are housed in Oakley Court, made up of undergraduates.[192] Oakley Court was completed in 1993 at a cost of £2.9 million. It was designed by Birmingham-based Associated Architects.[193] Pritchatts Road is a group of four private houses that were converted into student residences. There is a maximum of 16 bedrooms per house.[194]

Selly Oak Village

[edit]

Selly Oak Village consists of three residences in the Selly Oak and Bournbrook areas: Jarratt Hall, which is owned by the university, Douper Hall, and The Metalworks. As of 2008, the village had 637 bed spaces for students.[195]

Jarratt Hall is a large complex designed around a central courtyard and three landscaped areas. It housed 587 undergraduate students as of 2012.[196] Jarratt Hall did not accommodate postgraduate students until September 2013, due to ongoing refurbishment of kitchens and the heating system.[197]

The Manor House, Northfield

[edit]

The University of Birmingham also own the Northfield Manor House, having acquired the property from the Cadbury family in 1953. The property was used as The Manor House student accommodation until 2007, when the halls were found to be in need of restoration and refurbishment. In 2014, however, arsonists set a fire that gutted much of the property. The University of Birmingham has rebuilt and restored the property since then, and has converted much of the site into flats.[198]

Student Housing Co-operative accommodation

[edit]Birmingham Student Housing Co-operative was opened in 2014 by students of the university to provide affordable self managed housing for its members. The co-operative manages a property on Pershore Road in Selly Oak.[citation needed]

Notable people

[edit]Academics

[edit]

The faculty and staff members connected with the university include Nobel laureates Sir Norman Haworth (Professor of Chemistry, 1925–1948),[199] Sir Peter Medawar (Mason Professor of Zoology, 1947–1951),[30] John Robert Schrieffer (NSF Fellow at Birmingham, 1957),[200] David Thouless, Michael Kosterlitz,[201] and Sir Fraser Stoddart.[202]

Physicists include John Henry Poynting, Freeman Dyson, Sir Otto Frisch, Sir Rudolf Peierls, Sir Marcus Oliphant, Sir Leonard Huxley, Harry Boot, Sir John Randall, and Edwin Ernest Salpeter. Chemists include Sir William A. Tilden. Mathematicians include Jonathan Bennett, Henry Daniels, Daniela Kühn, Deryk Osthus, Daniel Pedoe and G. N. Watson. In music, faculty members include the composers Sir Edward Elgar and Sir Granville Bantock. Geologists include Charles Lapworth, Frederick Shotton, and Sir Alwyn Williams. In medicine, faculty members include Sir Melville Arnott and Sir Bertram Windle. Biologists include William Hillhouse and George Stephen West, both Mason Professors of Botany.

Author and literary critic David Lodge taught English from 1960 until 1987. Poet and playwright Louis MacNeice was a lecturer in classics 1930–1936. English novelist, critic, and man of letters Anthony Burgess taught in the extramural department (1946–50).[203] Richard Hoggart founded the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Sir Alan Walters was Professor of Econometrics and Statistics (1951–68) and later became Chief Economic Adviser to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Lord Zuckerman was Professor of Anatomy 1946–1968 and also served as chief scientific adviser to the British government from 1964 to 1971. Lord King of Lothbury was a Professor in the Faculty of Commerce and later became Governor of the Bank of England. Sir William James Ashley was first Dean and the founder of the Birmingham Business School.

Sir Nathan Bodington was Professor of Classics. Sir Michael Lyons was Professor of Public Policy from 2001 to 2006. Sir Kenneth Mather was Professor of genetics (1948) and recipient of the 1964 Darwin Medal. Sir Richard Redmayne was Professor of Mining and later became first Chief Inspector of Mines. The art historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner held a research post at the university. Sir Ellis Waterhouse was Barber Professor of Fine Art (1952–1970). Lord Cadman taught petroleum engineering and is credited with creating the course 'Petroleum Engineering'. The philosopher Sir Michael Dummett held an assistant lectureship at the university. Lord Borrie was a professor of law and dean of the faculty of law. Sir Charles Raymond Beazley was Professor of History. Prison reformer Margery Fry was first warden of University House.[204]

Vice-Chancellors and Principals include Sir Oliver Lodge, Lord Hunter of Newington, Sir Charles Grant Robertson, Sir Raymond Priestley, and Sir Michael Sterling.

Alumni

[edit]

Four Nobel Prize laureates are Birmingham University alumni: Francis Aston, Maurice Wilkins, Sir John Vane, and Sir Paul Nurse.[199] In addition soil scientist Peter Bullock contributed to the reports of the IPCC, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.[205]

The university's alumni in the sphere of British government and politics include: British Prime Ministers Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain;[15] Chief Minister of Gibraltar Joe Bossano; British cabinet minister and UN Under-Secretary-General Baroness Amos; Cabinet Ministers Julian Smith and Hilary Armstrong; British ministers of state Ann Widdecombe, Richard Tracey, Derek Fatchett, and Anna Soubry; British High Commissioner to New Zealand and Ambassador to South Africa Sir David Aubrey Scott; Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands Nigel Dakin; Welsh Assembly Government minister Jane Davidson; and UN weapons inspector David Kelly.

Birmingham's alumni in the field of government and politics in other countries include Prime Minister of St. Lucia Kenny Anthony; Prime Minister of the Bahamas Perry Christie; Singapore Minister of Finance Hu Tsu Tau Richard; Singapore Senior Minister of State Matthias Yao; Minister of Defence of Kenya Mohamed Yusuf Haji; Tanzanian minister Mark Mwandosya; Tongan minister ʻAna Taufeʻulungaki; Ethiopian cabinet minister Junedin Sado; Deputy Prime Minister of Mauritius Rashid Beebeejaun; Saudi minister Abdulaziz bin Mohieddin Khoja; Foreign Minister of Gambia Bala Garba Jahumpa; Ghanaian minister Juliana Azumah-Mensah; Egyptian Minister William Selim Hanna; Nigerian minister Emmanuel Chuka Osammor; Saint Lucian minister Alvina Reynolds; Lebanese foreign minister Lucien Dahdah; Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema and Zimbabwean ministers David Karimanzira and Didymus Mutasa.

Alumni in the world of business include: director of the Bank of England Lord Roll of Ipsden; CEO of J Sainsbury plc Mike Coupe; Chairman of the Shell Transport and Trading Company plc Sir John Jennings; automobile executive Sir George Turnbull; President of the Confederation of British Industry Sir Clive Thompson; CEO and chairman of BP Sir Peter Walters; Chairman of British Aerospace Sir Austin Pearce; mobile communications entrepreneur Mo Ibrahim; fashion designer and retailer George Davis; founder of Osborne Computer Corporation Adam Osborne; and chairman & CEO of Bass plc Sir Ian Prosser.

Alumni in the legal arena include Hong Kong Chief Justice of the Court of Final Appeal Geoffrey Ma Tao-li; Hong Kong Judge of the Court of Final Appeal Robert Tang; Justice of Appeal at the Court of Appeal in Tanzania Robert Kisanga; Justice of the Supreme Court of Belize Michelle Arana; Lord Justice of Appeal Sir Philip Otton; and High Court Judges Dame Nicola Davies, Sir Michael Davies, Sir Henry Globe, and Dame Lucy Theis.

Alumni in the armed forces include Chief of the General Staff General Sir Mike Jackson; and Director General of the Army Medical Services Alan Hawley.

Alumni in the sphere of religion include Metropolitan Archbishop and Primate of the Anglican Church in South East Asia Bolly Lapok; Anglican Bishops Paul Bayes, Alan Smith, Stephen Venner, Michael Langrish, and Eber Priestley; Anglican Suffragan Bishops Brian Castle and Colin Docker; Catholic Archbishop Kevin McDonald; and Catholic bishop Philip Egan.

Alumni in the field of healthcare include: chair of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence David Haslam; Dame Hilda Lloyd, the first woman to be elected as president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; Chief Scientific Officer in the NHS Sue Hill; Chief Dental Officer for England Barry Cockcroft; and Chief Medical officer for England Sir Liam Donaldson.

Alumni in the domain of engineering include: Chairman of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority and of the Central Electricity Generating Board Lord Marshall of Goring; Chairman of British Aerospace Sir Austin Pearce; Chief Engineer of the PWD Shaef in World War II Sir Francis McLean; and Director of Production at the Ministry of Munitions during World War I Sir Henry Fowler.

Alumni in the creative industries include actors Madeleine Carroll, Tim Curry, Tamsin Greig, Matthew Goode, Nigel Lindsay, Elliot Cowan, Geoffrey Hutchings, Judy Loe, Jane Wymark, Mariah Gale, Hadley Fraser, Elizabeth Henstridge, and Norman Painting; actors and comedians Victoria Wood and Chris Addison; dancer/choreographer and co-creator of 'Riverdance' Jean Butler, social media influencer and YouTuber Hannah Witton, children's author and scholar Fawzia Gilani-Williams, author Polly Ho-Yen, musicians Simon Le Bon of Duran Duran and Christine McVie of Fleetwood Mac, and travel writer Alan Booth.

Alumni in academia include: University Vice-Chancellors Frank Horton, Sir Robert Howson Pickard, Sir Louis Matheson, Derek Burke, Sir Alex Jarratt, Sir Philip Baxter, Vincent Watts, P. B. Sharma, Berrick Saul, and Wahid Omar; neurobiologist and Emeritus Professor at the University of Cambridge Sir Gabriel Horn, physicians Sir Alexander Markham, Sir Gilbert Barling, Brian MacMahon, Aaron Valero, and Sir Arthur Thomson; neurologist Sir Michael Owen; physicists John Stewart Bell, Sir Alan Cottrell, Lord Flowers, Harry Boot, Elliott H. Lieb (recipient of the 2003 Henri Poincaré Prize), Stanley Mandelstam, Edwin Ernest Salpeter (recipient of the 1997 Crafoord Prize in Astronomy), Sir Ernest William Titterton, and Raymond Wilson (recipient of the 2010 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics); statistician Peter McCullagh; chemist Sir Robert Howson Pickard; biologists Sir Kenneth Murray and Lady Noreen Murray; zoologists Desmond Morris and Karl Shuker; behavioural neuroscientist Barry Everitt; palaeontologist Harry B. Whittington; computer scientist Mike Cowlishaw; Women's writing academic Lorna Sage; philosopher John Lewis; economist and historian Homa Katouzian; theologian and biochemist Arthur Peacocke; labour economist David Blanchflower; Professor of Social Policy at the London School of Economics Sir John Hills; geographer Geoffrey J.D. Hewings; Professor of Geology and ninth President of Cornell University Frank H. T. Rhodes; Government Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Alan Cottrell; and former astronaut Rodolfo Neri Vela.

Alumni in the world of sport are many. They include Lisa Clayton, the first woman to sail the globe single-handed; 400 metres runner Allison Curbishley, who won silver at the 1998 Commonwealth Games; team pursuit cyclist Paul Manning, who won bronze, silver and gold at the Olympics of 2004, 2008 and 2012; sports scholar Izzy Christiansen, who played football for Birmingham City, Everton and Manchester City before her call up to the senior England squad; Warwickshire and England cricketer Jim Troughton; and Adam Pengilly who competed as a skeleton racer at the 2006 and 2010 Winter Olympics and was elected to the International Olympic Committee Athletes' Commission in 2010.[206]

Triathlete Chrissie Wellington and Rachel Joyce won the ITU Long Distance World Championship in 2008 and 2011, and Chrissie holds the four fastest times in the World Ironman competition. She received an OBE in 2009, and the current world-class gym at the Sport & Fitness club on campus is named in her honour.

Whilst still studying at the university, student Lily Owsley scored the field hockey gold medal-winning goal at the 2016 Rio Olympics with the help of teammate and fellow UoB graduate Sophie Bray.

Middle-distance athlete Hannah England won the World Championship 1500m silver in 2011[207] and after retiring from athletics officially in 2019, worked alongside fellow athlete and husband Luke Gunn in the Sport department at the university.[208]

In recent years, Birmingham has seen scholars such as athletes Jonny Davies, 2020 British indoor champion over 3000m; Sarah McDonald, a former 1500m British Champion, and Mari Smith, the current British indoor silver medallist over 800m pass through the doors. Fran Williams, senior England netballer player, won Bronze with the England Roses at the Vitality Netball World Cup in Liverpool in 2019, the youngest player on the squad at 22 years old, and Laura Keates, England international rugby player, who was part of the 2014 World Cup-winning squad.[citation needed]

Barbara Slater, daughter of Wolverhampton Wanderer's legend and UoB's Director of Sport in 1972 Bill Slater, became Director of BBC Sport from 2009, and was the first woman to hold this title. She led the broadcast of the London 2012 Olympics – the biggest television event in British broadcasting history. Former Manchester United Chief Executive David Gill learned the ropes of financing at Birmingham, studying Industrial, Economic and Business Studies in 1978; sports commentator Simon Brotherton developed his career whilst studying at UoB, and Sir Patrick Head, founder of the Williams team which dominated Formula One in the 1990s, studied Mechanical Engineering.[citation needed]

Across disciplines, John Crabtree, who graduated in law in 1972, achieved success as a lawyer and businessman, was awarded the OBE for his charity work, and served as High Sheriff of the West Midlands and Lord Lieutenant of the West Midlands, and as chair of the 2022 Birmingham Commonwealth Games Organising Committee.[209]

See also

[edit]- Armorial of UK universities

- List of modern universities in Europe (1801–1945)

- List of universities in the United Kingdom

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ Includes those who indicate that they identify as Asian, Black, Mixed Heritage, Arab or any other ethnicity except White.

- ^ Calculated from the Polar4 measure, using Quintile1, in England and Wales. Calculated from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) measure, using SIMD20, in Scotland.

- ^ Anderson, Peter John (1907). Record of the Celebration of the Quatercentenary of the University of Aberdeen: From 25th to 28th September, 1906. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: Aberdeen University Press (University of Aberdeen). ASIN B001PK7B5G. ISBN 9781363625079.

- ^ Ives et al. 2000, p. 238.

- ^ a b c "Mason College". Birmingham University. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b Ives et al. 2000, p. 12.

- ^ a b c "Financial Statements for the Year to 31 July 2023" (PDF). University of Birmingham. p. 55. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ "Chancellors of the University of Birmingham". 1 August 2024. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ "Who's working in HE?". www.hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Agency.

- ^ a b c d "Where do HE students study?". Higher Education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Curtis, Polly (29 July 2005). "Birmingham University houses tornado victims". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Bawden, Anna (11 February 2005). "Muslim students threaten to sue Birmingham University". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ Whyte, William (16 January 2015). Redbrick: A Social and Architectural History of Britain's Civic Universities. ISBN 978-0-19-102522-8.

- ^ University guide 2014: University of Birmingham, The Guardian, 8 June 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- ^ "REF 2021: Golden triangle looks set to lose funding share". Times Higher Education. 12 May 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b "25 tallest clock towers/government structures/palaces" (PDF). Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. January 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2008.

- ^ a b K. Feiling, The Life of Neville Chamberlain (London, 1970), 11–12.

- ^ "Our Nobel Prize winners". University of Birmingham. Archived from the original on 9 August 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "History of the University of Birmingham Medical School, 1825 – 2001". University of Birmingham.

- ^ Gosden, Peter. "From County College To Civic University, Leeds, 1904", Northern History 42.2 (2005): 317-328. Academic Search Premier, Web. 12 November 2014.

- ^ "A Mermaid's Tale: the origins of the University's Crest". Research and Cultural Collections. University of Birmingham. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Keith Anderton, slevenotes, Bantock: Hebridean Symphony, Naxos 8.555473, 1989.

- ^ "Cadbury Research Library – Special Collections". University of Birmingham.

- ^ a b "Our Impact" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ McNair, Philip (January 1977). "Linetta de Castelvecchio Richardson". Italian Studies. 32 (1). The Society for Italian Studies: 1–3. doi:10.1179/its.1977.32.1.1.