Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia Museum of Art's main building at Eakins Oval | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | February 1876[1] |

|---|---|

| Location | 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.[2] |

| Coordinates | 39°57′57″N 75°10′53″W / 39.96583°N 75.18139°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 240,000[3] |

| Visitors | 793,000 (2017)[4] |

| Director | Sasha Suda[5][6][7] |

| Chairperson | Ellen T. Caplan |

| Architect |

|

| Public transit access | |

| Website | www |

The Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) is an art museum originally chartered in 1876 for the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.[1] The main museum building was completed in 1928[8] on Fairmount, a hill located at the northwest end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway at Eakins Oval.[2] The museum administers collections containing over 240,000 objects including major holdings of European, American and Asian origin.[3] The various classes of artwork include sculpture, paintings, prints, drawings, photographs, armor, and decorative arts.[3]

The Philadelphia Museum of Art administers several annexes including the Rodin Museum, also located on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, and the Ruth and Raymond G. Perelman Building, which is located across the street just north of the main building.[9] The Perelman Building, which opened in 2007,[10] houses more than 150,000 prints, drawings and photographs, 30,000 costume and textile pieces, and over 1,000 modern and contemporary design objects including furniture, ceramics, and glasswork.[11]

The museum also administers the historic colonial-era houses of Mount Pleasant and Cedar Grove, both located in Fairmount Park.[12] The main museum building and its annexes are owned by the City of Philadelphia and administered by a registered nonprofit corporation.[9]

Several special exhibitions are held in the museum every year, including touring exhibitions arranged with other museums in the United States and abroad.[13][14] The museum had 437,348 visitors in 2021.

History

[edit]Early years (1877–1900)

[edit]Philadelphia celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence with the Centennial Exposition in 1876. Memorial Hall, which contained the art gallery, was intended to outlast the Exposition and house a permanent museum. Following the example of London's South Kensington Museum, the new museum was to focus on applied art and science, and provide a school to train craftsmen in drawing, painting, modeling, and designing.[1]

The Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art opened on May 10, 1877. The school became independent of the museum in 1964 and is now part of the University of the Arts. The museum's collection began with objects from the Exposition and gifts from the public impressed with the Exposition's ideals of good design and craftsmanship. European and Japanese fine and decorative art objects and books for the museum's library were among the first donations. The location outside of Center City, Philadelphia, however, was fairly distant from many of the city's inhabitants.[15] Admission was charged until 1881, then was dropped until 1962.[16]

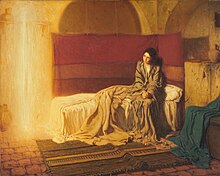

Starting in 1882, Clara Jessup Moore donated a remarkable collection of antique furniture, enamels, carved ivory, jewelry, metalwork, glass, ceramics, books, textiles and paintings. The Countess de Brazza's lace collection was acquired in 1894 forming the nucleus of the lace collection. In 1892 Anna H. Wilstach bequeathed a large painting collection, including many American paintings, and an endowment of half a million dollars for additional purchases. Works by James Abbott McNeill Whistler and George Inness were purchased within a few years and Henry Ossawa Tanner's The Annunciation was bought in 1899.[16]

Construction of the main building (1895–1933)

[edit]The City Council of Philadelphia funded a competition in 1895 to design a new museum building,[16] but it was not until 1907 that plans were first made to construct it on Fairmount, a rocky hill topped by the city's main reservoir. The Fairmount Parkway (renamed Benjamin Franklin Parkway), a grand boulevard that cut diagonally across the grid of city streets, was designed to terminate at the foot of the hill. But there were conflicting views about whether to erect a single museum building, or a number of buildings to house individual collections.

Horace Trumbauer and Zantzinger, Borie and Medary, both architectural firms, collaborated for more than a decade to resolve these issues. The final design is mostly credited to two architects in Trumbauer's firm: Howell Lewis Shay for the building's plan and massing, and Julian Abele for the detail work and perspective drawings.[17] In 1902, Abele had become the first African-American student to be graduated from the University of Pennsylvania's Department of Architecture, which is presently known as Penn's School of Design.[18] Abele adapted classical Greek temple columns for the design of the museum entrances, and was responsible for the colors of both the building stone and the figures added to one of the pediments.[19]

Construction of the main building began in 1919, when Mayor Thomas B. Smith laid the cornerstone in a Masonic ceremony. Because of shortages caused by World War I and other delays, the new building was not completed until 1928.[20] The building was constructed with dolomite quarried in Minnesota.[21] The wings were intentionally built first, to help assure the continued funding for the completion of the design. Once the building's exterior was completed, twenty second-floor galleries containing English and American art opened to the public on March 26, 1928, though a large amount of interior work was incomplete.[8]

The building's eight pediments were intended to be adorned with sculpture groups. The only pediment that has been completed, Western Civilization (1933) by C. Paul Jennewein, colored by Leon V. Solon, features polychrome sculptures of painted terra-cotta figures depicting Greek deities and mythological figures.[22] The sculpture group was awarded the Medal of Honor of the Architectural League of New York.[23]

The building is also adorned by a collection of bronze griffins, which were later adopted as the symbol of the museum in the 1970s.[15]

Membership program and growth (1928–1976)

[edit]

In the early 1900s, the museum started an education program for the general public, as well as a membership program.[24] Fiske Kimball was the museum director during the rapid growth of the mid- to late-1920s, which included one million visitors in 1928—the new building's first year. The museum enlarged its print collection in 1928 with about 5,000 Old Master prints and drawings from the gift of Charles M. Lea, including French, German, Italian, and Netherlandish engravings.[8] Major exhibitions of the 1930s included works by Eakins, Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, van Gogh, and Degas.[25]

In the 1940s, the museum's major gifts and acquisitions included the collections of John D. McIlhenny (Oriental carpets), George Grey Barnard (sculpture), and Alfred Stieglitz (photography).[26]

Early modern art dominated the growth of the collections in the 1950s, with acquisitions of the Louise and Walter Arensberg and the A.E. Gallatin collections. The gift of Philadelphian Grace Kelly's wedding dress is perhaps the best known gift of the 1950s.[20]

Extensive renovation of the building lasted from the 1960s through 1976. Major acquisitions included the Carroll S. Tyson, Jr. and Samuel S. White III and Vera White collections, 71 objects from designer Elsa Schiaparelli, and Marcel Duchamp's Étant donnés. In 1976 there were celebrations and special exhibitions for the centennial of the museum and the bicentennial of the nation. During the last three decades major acquisitions have included After the Bath by Edgar Degas and Fifty Days at Iliam by Cy Twombly.[20]

Building expansion (2004–present)

[edit]

Due to high attendance and overflowing collections, the museum announced in October 2006 that Frank Gehry would design a building expansion. The 80,000-square-foot (7,400 m2) gallery will be built entirely underground behind the east entrance stairs and will not alter any of the museum's existing Greek revival facade. The construction was initially projected to last a decade and cost $500 million. It will increase the museum's available display space by sixty percent and house mostly contemporary sculpture, Asian art, and special exhibitions.[27][28]

Uncertainty was cast on the plans by the 2008 death of Anne d'Harnoncourt, but new director Timothy Rub, who had initiated a $350 million expansion at the Cleveland Museum of Art, will be carrying out the plans as scheduled. In 2010, Gehry attended the groundbreaking for the second phase of the expansion, due to be completed in 2012. In that phase, a new art handling facility was created on the south side of the building, enabling the museum to reclaim a street level entrance, closed since the mid-1970s, which leads to a 640-foot (200 m)-long vaulted walkway that extends across the museum and is original to the 1928 building.[29] The north entrance will be reopened to the public as a part of the "core project", which is scheduled for completion in 2020.[30] The core project also focuses on the interior of the current building and will add 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2) of public space, including 11,500 square feet (1,070 m2) of new gallery space for American art and contemporary art.[31] In addition, a new space called the forum will be created, along with dining and retail spaces. Said Gehry: "When it's done, people coming to this museum will have an experience that's as big as Bilbao. It won't be apparent from the outside, but it will knock their socks off inside."[28][32]

In March 2017, the museum announced a $525 million campaign.[31] The core project is budgeted at $196 million and will be funded through the campaign.[31] The museum also announced that more than 62 percent of the campaign goal has been met, as of March 30, 2017.[31]

In March 2020, the museum was officially temporarily closed due to COVID-19 pandemic. All public events and programs were canceled until August 31, 2020. The museum reopened by late September 2020.[33]

The most controversial part of the Gehry design remains a proposed window and amphitheater to be cut into the east entrance stairs.[34] Others have criticized the design as too tame.[35] The Gehry expansion is projected to be completed by 2028.[36]

Collections

[edit]

The Philadelphia Museum of Art houses more than 240,000 objects,[3] highlighting the creative achievements of the Western world and those of Asia, in more than 200 galleries spanning 2,000 years.[37] The museum's collections of Egyptian and Roman art, and Pre-Columbian works, were relocated to the Penn Museum after an exchange agreement was made whereby the museum houses the university's collection of Chinese porcelain.[38]

Highlights of the Asian collections include paintings and sculpture from China, Japan, and India; furniture and decorative arts, including major collections of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean ceramics; a large and distinguished group of Persian and Turkish carpets; and rare and authentic architectural assemblages such as a Chinese palace hall, a Japanese teahouse, and a 16th-century Indian temple hall.[3]

The European collections, dating from the medieval era to the present, encompass Italian and Flemish early-Renaissance masterworks; strong representations of later European paintings, including French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism; sculpture, with a special concentration in the works of Auguste Rodin; decorative arts; tapestries; furniture; the second-largest collection of arms and armor in the United States; and period rooms and architectural settings ranging from the facade of a medieval church in Burgundy to a superbly decorated English drawing room by Robert Adam.[3]

The museum's American collections, surveying more than three centuries of painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, are among the finest in the United States, with outstanding strengths in 18th- and 19th-century Philadelphia furniture and silver, Pennsylvania German art, rural Pennsylvania furniture and ceramics, and the paintings of Thomas Eakins. The museum houses the most important Eakins collection in the world.[3]

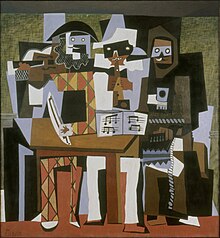

Modern artwork includes works by Pablo Picasso, Jean Metzinger, Antonio Rotta, Albert Gleizes, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalí and Constantin Brâncuși, as well as American modernists. The expanding collection of contemporary art includes major works by Agnes Martin, Cy Twombly, Jasper Johns, and Sol LeWitt, among many others.[3]

The museum houses encyclopedic holdings of costume and textiles, as well as prints, drawings, and photographs that are displayed in rotation for reasons of preservation.[3]

The Carl Otto Kretzschmar von Kienbusch Collection

[edit]

The museum also houses the armor collection of Carl Otto Kretzschmar von Kienbusch. The Von Kienbusch collection was bequeathed by the celebrated collector to the museum in 1976, the Bicentennial Anniversary of the American Revolution. The Von Kienbusch holdings are comprehensive and include European and Southwest Asian arms and armor spanning several centuries.[39]

On May 30, 2000, the museum and the State Art Collections in Dresden, Germany (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden), announced an agreement for the return of five pieces of armor stolen from Dresden during World War II.[40] In 1953, Von Kienbusch had unsuspectingly purchased the armor, which was part of his 1976 bequest. Von Kienbusch published catalogs of his collection, which eventually led Dresden authorities to bring the matter up with the museum.[41][42]

Special exhibitions

[edit]The Philadelphia Museum of Art organizes several special exhibitions each year.[13][14] Special exhibitions have featured Salvador Dalí in 2005,[43] Paul Cézanne in 2009,[44] Auguste Renoir in 2010,[45] Vincent van Gogh in 2012,[46] Pablo Picasso in 2014,[47] John James Audubon and Andy Warhol (et al.) in 2016,[48] Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent in 2017,[49] and the Duchamp siblings—Marcel, Gaston, Raymond and Suzanne—in 2019.[50] A Jasper Johns exhibition is planned for 2021.[51][52]

In 2009, the museum organized Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens, the official United States entry at the 53rd International Art Exhibition, more commonly known as the Venice Biennale, for which the artist Bruce Nauman was awarded the Golden Lion.[53]

Administration

[edit]Directors

[edit]

The directors of the Philadelphia Museum of Art since its inception are:

- Sasha Suda, 2022–Present[54][6]

- Timothy Rub, 2009–2022[55]

- Anne d'Harnoncourt, 1982–2008

- Jean Sutherland Boggs, 1978–1982[56]

- Evan Hopkins Turner, 1964–1977[57]

- Arnold H. Jolles, 1977–1979 (acting)[58]

- Henri Gabriel Marceau, 1955–1964[59]

- Fiske Kimball, 1925–1955

- Sr. Samuel W. Woodhouse, 1923–1925 (acting)[60]

- Langdon Warner, 1917–1923[61]

- Edwin Atlee Barber, 1907–1916[62]

- William Platt Pepper, 1899–1907

- Dalton Dorr, 1892–1899[63]

- William W. Justice, 1879–1880

- William Platt Pepper, 1877–1879

Board of trustees

[edit]Below is the list of chairs of the board of trustees of the museum since 1991.

- Ellen T. Caplan 2023 – present

- Leslie A. Miller 2016 – 2023

- Constance H. Williams 2010–2016

- Gerry Lenfest 2001–2009

- Raymond Perlman 1991–2001[64]

Looted art controversies

[edit]In December 2021, the heirs of Piet Mondrian filed a lawsuit against the museum for Composition with Blue, which the artist had consigned to Küppers-Lissitzky when it was seized by the Nazis.[65][66][67] The same year, the museum announced that it would return an ancient 'Pageant Shield' looted by Nazis to the Czech Republic.[68]

Gallery

[edit]-

Rogier van der Weyden, Crucifixion Diptych, c. 1460

-

Hieronymus Bosch, Epiphany, c. 1475–1480

-

Peter Paul Rubens, Prometheus Bound, 1611–12

-

Alfred Stevens, Will you go out with me, Fido?, 1859

-

Édouard Manet, The Battle of The Alabama and Kearsarge, 1864

-

Thomas Eakins, The Gross Clinic, 1875

-

Thomas Eakins, William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of Schuylkill River, 1876–1877

-

Édouard Manet, Portrait of Émilie Ambre as Carmen, 1880

-

Winslow Homer, The Life Line, 1884

-

Claude Monet, Poplars (Autumn), 1891

-

Thomas Eakins, The Concert Singer, 1890–1892

-

Claude Monet, Japanese Bridge and Water Lilies, c. 1899

-

Paul Cézanne, The Bathers, 1898–1905

-

Pablo Picasso, Old Woman (Woman with Gloves), 1901

-

Gino Severini, La Modiste (The Milliner), 1910–11

-

Marc Chagall, Trois heures et demie (Le poète), Half-Past Three (The Poet), 1911

-

Marcel Duchamp, La sonate (Sonata), 1911

-

Jean Metzinger, Le goûter (Tea Time), 1911 – André Salmon dubbed this painting "The Mona Lisa of Cubism"

-

Francis Picabia, The Dance at the Spring, 1912

-

Juan Gris, Chessboard, Glass, and Dish, 1917

-

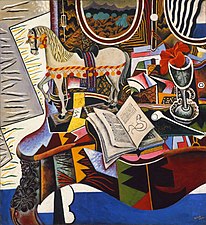

Joan Miró, 1920, Horse, Pipe and Red Flower

In popular culture

[edit]

Besides being known for its architecture and collections, the Philadelphia Museum of Art has in recent decades become known due to the role it played in the Rocky films—Rocky (1976) and seven of its eight sequels, II, III, V, Rocky Balboa, Creed, Creed II, and Creed III. Visitors to the museum are often seen mimicking Rocky Balboa's (portrayed by Sylvester Stallone) famous run up the east entrance stairs, informally nicknamed the Rocky Steps.[69] Screen Junkies named the museum's stairs the second most famous movie location behind only Grand Central Station in New York.[70]

An 8.5 ft (2.6 m) tall bronze statue of the Rocky Balboa character was commissioned in 1980 and placed at the top of the stairs in 1982 for the filming of Rocky III. After filming was complete, Stallone donated the statue to the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia Art Commission eventually decided to relocate the statue to the now-defunct Spectrum sports arena due to controversy over its prominent placement at the top of the museum's front stairs and questions about its artistic merit. The statue was placed briefly on top of the stairs again for the 1990 film Rocky V and then returned to the Spectrum. In 2006, the statue was relocated to a new display area on the north side of the base of the stairs.[71][72]

The museum provides the backdrop for concerts and parades because of its location at the end of the Ben Franklin Parkway. The museum's east entrance area played host to the American venue of the international Live 8 concert held on July 2, 2005, with musical artists including Dave Matthews Band, Linkin Park and Maroon 5.[73] The Philadelphia Freedom Concert, orchestrated and headlined by Elton John, was held two days later on the same outdoor stage from the Live 8 concert[74] while a preceding ball was held inside the museum.[75]

On September 26, 2015, the Festival of Families event, attended by Pope Francis, was held along the Ben Franklin Parkway with musical performances by various acts within Eakins Oval in front of the museum, as well as in Logan Square.[76][77][78]

On April 27, 2017, the 2017 NFL draft was held at the museum through April 29 of that year.

On February 8, 2018, the victory parade for the Philadelphia Eagles' win in Super Bowl LII finished upon the museum steps, where players and team personnel gave speeches from a lectern to the large crowd gathered along Ben Franklin Parkway.[79]

It was featured on the finale of The Amazing Race 36.

See also

[edit]- 3rd Sculpture International

- 70 Sculptors, photograph by Herbert Gehr

- Barnes Foundation

- Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

- Woodmere Art Museum

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Centennial Origins: 1874–1876". History. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ a b "Philadelphia Museum of Art: Homepage". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Search Collections". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ Robert T. Rambo (n.d.). "2017 Annual Report" (PDF). Philadelphia Museum of Art. p. 19 (of PDF file). Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2018. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

Admission income of $5.4 million and attendance of 793,000 were essentially at the same levels as 2016.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - About Us : Administration". www.philamuseum.org. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Kinsella, Eileen (June 7, 2022). "National Gallery of Ontario Director Sasha Suda Will Leave to Helm the Philadelphia Museum of Art". Artnet News. Retrieved June 8, 2022.

- ^ "Meet Sasha Suda, Philadelphia Museum of Art's new CEO and director". www.audacy.com. June 8, 2022. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Philadelphia Museum of Art: About Us: Our Story: 1920–1930". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ^ a b "About Us: Administration". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ "About Us : Our Story : Perelman Building - Renovations and Expansion". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "About Us : Our Story : Perelman Building – Galleries & Spaces". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 3, 2016.

- ^ "Visiting : Plan Your Visit : Historic Houses" Archived December 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "On View: Past Exhibitions". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "On View: Current Exhibitions". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "Philadelphia Museum of Art :: Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States". Glass Steel and Stone. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c "The Early Decades: 1877–1900". philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- ^ David B. Brownlee, Making a Modern Classic: The Architecture of the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997), pp. 60–61, 72–73.

- ^ Tatman, Sandra L. "Abele, Julian Francis (1881 - 1950) Architect". philadelphiabuildings.org. The Athenaeum of Philadelphia. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ "Julian Francis Abele (1881-1950): First African American graduate of the School of Fine Arts". design.upenn.edu. University of Pennsylvania School of Design. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ a b c "An Overview of the Museum's History". philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Galleries and Gardens: Discover blossoming works of art in Philadelphia's green spaces". With Art Philadelphia. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Samuels, Tanyanika (June 2, 2011). "Bronx street rename for borough's own sculptor Carl Paul Jennewein". The New York Daily News. p. 31. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Lowey, Nita M. "New York: C. Paul Jennewein, Sculptor (Local Legacies: Celebrating Community Roots - Library of Congress)". Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "About Us: Our Story: 1900-1910" Archived March 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "About Us: Our Story: 1930-1940" Archived March 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "About Us: Our Story: 1940-1950" Archived July 11, 2018, at the Wayback Machine. philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Pogrebin, Robin (October 19, 2006). "Philadelphia Museum Job Sends Gehry Underground". New York Times.

- ^ a b PMA web site Archived May 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine "Master Plan", accessed, May 10, 2012

- ^ "Frank Gehry's Quiet Intervention at the Philadelphia Museum of Art" Archived July 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Plan Philly, Accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Romero, Melissa. "5 Ways the Philadelphia Museum of Art will look different in 2020" Archived April 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Curbed Philadelphia, Accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Cascone, Sarah. "Philadelphia Museum of Art Aims to Raise $525 Million for Frank Gehry Designed Expansion" Archived June 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Artnet, Accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Associated Press (November 22, 2011). "Philly museum starts Gehry expansion". USA TODAY. Retrieved May 11, 2012.

- ^ Crimmins, Peter (August 10, 2020). "Philadelphia Museum of Art announces September reopening". WHYY. Archived from the original on December 6, 2022. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ Gehry architectural model Archived June 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Magazine, June 26, 2014.

- ^ Heller: "If you're going to hire Gehry, Let's do Gehry," Archived October 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Philadelphia Magazine, August 11, 2014.

- ^ Gehry section through museum Archived July 2, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Magazine, July 2, 2014.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art: About". ARTINFO. 2008. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Frequently Asked Questions: What does the Museum's collection include?" (archive). philamuseum.org. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Philadelphia Museum of Art - Information : Press Room : Press Releases : 2004". Philamuseum.org. September 27, 2004. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "PMA press release". Philamuseum.org. December 16, 1999. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Larocca, Donald J. (1985). "Carl Otto Kretzschmar von Kienbusch and the Collecting of Arms and Armor in America". Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin. 81 (345): 2+4-24. doi:10.2307/3795448. JSTOR 3795448.

- ^ Armor Collection Archived December 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine at arthistorians.info.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2005 - Salvador Dalí". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2009 - Cézanne and Beyond". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2010 - Late Renoir". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2012 - Van Gogh Up Close". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2014 - Picasso Prints: Myths, Minotaurs, and Muses". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2016 - Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "On View: Past Exhibitions: 2017 - American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- ^ "The Duchamp Family". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Cummings, Sinead (March 3, 2020). "Jasper Johns exhibition to be split between Philadelphia and New York". www.phillyvoice.com. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens" Archived August 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Accessed May 14, 2017.

- ^ Union Members at the Philadelphia Museum of Art On Strike Indefinitely, as New Director Starts Archived October 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, ArtNews, Accessed online October 7, 2022

- ^ "Timothy Rub, the George D. Widener Director and CEO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, to Retire on January 30, 2022". Timothy Rub, the George D. Widener Director and CEO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, to Retire on January 30, 2022. Retrieved May 7, 2022.

- ^ Jean Sutherland Boggs records Archived September 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ Evan H. Turner records Archived September 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ "Arnold H. Jolles Records" Archived August 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art Archives, Accessed online April 16, 2017.

- ^ Henri Gabriel Mareau Director records Archived September 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ "Our Story: 1920 – 1930" Archived March 14, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Accessed April 16, 2017.

- ^ Langdon Warner records Archived September 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ Edwin Atlee Barber records Archived September 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ Dalton Dorr records Archived September 19, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, from Philadelphia Museum of Art.

- ^ "Constance H. Williams Announces Leslie A. Miller as Her Successor as the Museum's Board of Trustees Chair". Constance H. Williams Announces Leslie A. Miller as Her Successor as the Museum's Board of Trustees Chair. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (December 13, 2021). "Mondrian Heirs Sue Philadelphia Museum, Claiming Painting Was Looted by Nazis". ARTnews.com. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ "Mondrian at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is Nazi loot, heirs allege". The Art Newspaper - International art news and events. December 14, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ Hickley, Catherine (December 13, 2021). "Heirs Sue to Claim Mondrian Painting in Philadelphia Museum of Art". New York Times.

- ^ Kinsella, Eileen (September 14, 2021). "The Philadelphia Museum of Art Will Return an Ancient 'Pageant Shield' Looted by Nazis to the Czech Republic". Artnet News. Retrieved January 25, 2024.

- ^ The Rocky Statue and the Rocky Steps Archived March 9, 2018, at the Wayback Machine visitphilly.com, accessed June 17, 2011.

- ^ 10 Most Famous Movie Locations Archived November 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Screen Junkies

- ^ Avery, Ron. "Philadelphia Oddities - Rocky Statue". Independence Hall Association. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Holzman, Laura (2013). "Rocky". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Live 8 Philadelphia (scroll down), Archive.org, July 2, 2005

- ^ The Philadelphia Freedom Concert, Archive.org, July 4, 2005

- ^ The Philadelphia Freedom Ball, Archive.org, July 4, 2005

- ^ "Festival of Families" (archive). worldmeeting2015.org. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Jim Yardley and Daniel J. Wakin (September 26, 2015). "At Independence Hall, Pope Offers a Broad Vision of Religious Freedom" (archive). nytimes.com. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "The Pope's Visit to Philadelphia" (archive). visitphilly.com. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Eric Levenson and David Williams (February 8, 2018). "Eagles fans flock to Philadelphia streets for Super Bowl parade" (archive). cnn.com. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

External links

[edit] Media related to Philadelphia Museum of Art at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Philadelphia Museum of Art at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1661, "Philadelphia Museum of Art, Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, PA", 6 photos, 4 color transparencies, 3 photo caption pages

- Listing at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings, including more than 800 images, mostly of the main building's construction

- "Philadelphia Museum of Art" at Google Arts & Culture

- Philadelphia Museum of Art

- 1876 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Art museums and galleries in Philadelphia

- Art museums and galleries established in 1876

- Asian art museums in the United States

- Benjamin Franklin Parkway

- East Fairmount Park

- Fairmount, Philadelphia

- Horace Trumbauer buildings

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Philadelphia

- Museums of American art

- Philadelphia Register of Historic Places

- Terminating vistas in the United States