National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 29 December 1970 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | Federal Government of the United States |

| Headquarters | Washington, D.C. |

| Employees | 1,300 |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| Website | www |

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH, /ˈnaɪɒʃ/) is the United States federal agency responsible for conducting research and making recommendations for the prevention of work-related injury and illness. NIOSH is part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Despite its name, it is not part of either the National Institutes of Health nor OSHA. Its current director is John Howard.

NIOSH is headquartered in Washington, D.C., with research laboratories and offices in Cincinnati, Ohio; Morgantown, West Virginia; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Denver, Colorado; Anchorage, Alaska; Spokane, Washington; and Atlanta, Georgia.[1] NIOSH is a professionally diverse organization with a staff of 1,200 people representing a wide range of disciplines including epidemiology, medicine, industrial hygiene, safety, psychology, engineering, chemistry, and statistics.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act, signed by President Richard M. Nixon on December 29, 1970, created NIOSH out of the preexisting Division of Industrial Hygiene founded in 1914. NIOSH was established to help ensure safe and healthful working conditions by providing research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health. NIOSH provides national and world leadership to prevent work-related illness, injury, disability, and death by gathering information, conducting scientific research, and translating the knowledge gained into products and services.[2] Although NIOSH and OSHA were established by the same Act of Congress, the two agencies have distinct and separate responsibilities.[3] NIOSH has several "virtual centers" through which researchers at its geographically dispersed locations are linked by shared computer networks and other technologies that stimulates collaboration and helps overcome the challenges of working as a team across distances.[4]

Authority

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Respirators in the United States |

|---|

| Executive agencies involved |

| Non-government bodies |

| Respirator regulation |

| Diseases mitigated by respirators |

| Misuse |

| Related topics involving respirators |

Unlike its counterpart, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, NIOSH's authority under the Occupational Safety and Health Act [29 CFR § 671] is to "develop recommendations for health and safety standards", to "develop information on safe levels of exposure to toxic materials and harmful physical agents and substances", and to "conduct research on new safety and health problems". NIOSH may also "conduct on-site investigations (Health Hazard Evaluations) to determine the toxicity of materials used in workplaces" and "fund research by other agencies or private organizations through grants, contracts, and other arrangements".[2]

Also, pursuant to its authority granted to it by the Mine Safety and Health Act of 1977, NIOSH may "develop recommendations for mine health standards for the Mine Safety and Health Administration", "administer a medical surveillance program for miners, including chest X‑rays to detect pneumoconiosis (black lung disease) in coal miners", "conduct on-site investigations in mines similar to those authorized for general industry under the Occupational Safety and Health Act; and "test and certify personal protective equipment and hazard-measurement instruments".[2]

Respirators

[edit]Under 42 CFR 84, NIOSH has the right to issue and revoke certifications for respirators, such as the N95.[5] Currently, NIOSH is the only body authorized to regulate respirators, and has trademark rights to the NIOSH air filtration ratings.[6]

Products and publications

[edit]

NIOSH research covers a wide range of fields. The knowledge obtained through intramural and extramural research programs is used to develop products and publication offering innovative solutions for a wide range of work settings. Some of the publications produced by NIOSH include:

- Alerts are put out by the agency to request assistance in preventing, solving, and controlling newly identified occupational hazards. They briefly present what is known about the risk for occupational injury, illness, and death.

- Criteria Documents contain recommendations for the prevention of occupational diseases and injuries. These documents are submitted to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration or the Mine Safety and Health Administration for consideration in their formulation of legally binding safety and health standards.

- Current Intelligence Bulletins analyze new information about occupational health and safety hazards.

- The National Agricultural Safety Database contains citations and summaries of scholarly journal articles and reports about agricultural health and safety.

- The Fatality Assessment and Control Evaluation program publishes occupational fatality data that are used to publish fatality reports by specific sectors of industry and types of fatal incidents.[7]

- The Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program investigates the causes of specifically firefighter deaths on the job.

- The NIOSH Power Tools Database contains sound power levels, sound pressure levels, and vibrations data for a variety of common power tools that have been tested by NIOSH researchers.

- The NIOSH Hearing Protection Device Compendium contains attenuation information and features for commercially available earplugs, earmuffs and semi-aural insert devices (canal caps).[8]

- NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods contains recommendations for collection, sampling and analysis of contaminants in the workplace and industrial hygiene samples, including air filters, biological fluids, wipes and bulks for occupationally relevant analytes.[9]

- The NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards informs workers, employers, and occupational health professionals about workplace chemicals and their hazards.[10]

National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory

[edit]The National Personal Protective Technology Laboratory (NPPTL) is a research center within the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health located in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, devoted to research on personal protective equipment (PPE). The NPPTL was created in 2001 at the request of the U.S. Congress, in response to a recognized need for improved research in PPE technologies.[11][12] It focuses on experimentation and recommendations for respirator masks, by ensuring a level of standard filter efficiency, and develops criteria for testing and developing PPE.[11][12][13]

The laboratory conducts research and provides recommendations for other types of PPE, including protective clothing, gloves, eye protection, headwear, hearing protection, chemical sensors, and communication devices for safe deployment of emergency workers. It also maintains certification for N95 respirators,[11] and hosts an annual education day for N95 education.[14] Its emergency response research is part of a collaboration with the National Fire Protection Association.[12]

In the 2010s, the NPPTL has focused on pandemic influenza preparedness, CBRNE incidents, miner PPE, and nanotechnology.[15]

The NIOSH NPPTL Certified Equipment List details the respirators currently approved by NIOSH.[16]

Education and Research Centers

[edit]

NIOSH Education and Research Centers are multidisciplinary centers supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health for education and research in the field of occupational health. Through the centers, NIOSH supports academic degree programs and research opportunities, as well as continuing education for OSH professionals.[17] The ERCs, distributed in regions across the United States, establish academic, labor, and industry research partnerships.[18] The research conducted at the centers is related to the National Occupational Research Agenda (NORA) established by NIOSH.[19]

Founded in 1977, NIOSH ERCs are responsible for nearly half of post-baccalaureate graduates entering occupational health and safety fields. The ERCs focus on industrial hygiene, occupational health nursing, occupational medicine, occupational safety, and other areas of specialization.[20] At many ERCs, students in specific disciplines have their tuition paid in full and receive additional stipend money. ERCs provide a benefit to local businesses by offering reduced price assessments to local businesses.

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]

NIOSH's earliest predecessor was the U.S. Public Health Service Office of Industrial Hygiene and Sanitation, established in 1914. It went through several name changes, most notably becoming the Division of Industrial Hygiene and later the Division of Occupational Health.[21][22] Its headquarters were established in Washington, D.C. in 1918, and field stations in Salt Lake City in 1949, and in Cincinnati in 1950.[22][23]

NIOSH was created by the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970[24] and began operating in May 1971.[22] It was originally part of the Health Services and Mental Health Administration, and was transferred into what was then called the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in 1973.[24] NIOSH's initial headquarters were located in Rockville, Maryland.[23]

Prior to 1976, NIOSH's Cincinnati operations occupied space at three locations in Downtown Cincinnati, and rented space at 5555 Ridge Avenue in the Pleasant Ridge neighborhood.[25] In 1976, staff at the Downtown locations were relocated to the Robert A. Taft Center in the Columbia-Tusculum neighborhood, which the Environmental Protection Agency was vacating to occupy the new Andrew W. Breidenbach Environmental Research Center elsewhere in Cincinnati.[25][26] The Taft Center had opened in 1954 for the PHS as the Robert A. Taft Sanitary Engineering Center,[27][28] named for the then-recently deceased Senator Robert A. Taft,[29] and the center had become part of the newly formed Environmental Protection Agency in 1970.[26][27]

The 5555 Ridge Avenue building had been constructed during 1952–1954 and was initially the headquarters and manufacturing plant of Disabled American Veterans.[30] PHS had leased space in the 5555 Ridge Avenue building beginning in 1962.[31] By 1973 the entire building was leased by the federal government, and in 1982 it was purchased outright by the PHS. In 1987 it was renamed the Alice Hamilton Laboratory for Occupational Safety and Health, after occupational health pioneer Alice Hamilton.[30]

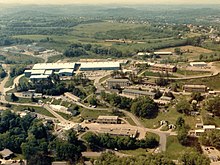

The Appalachian Laboratory for Occupational Respiratory Diseases, which had been created within the PHS in 1967 to focus on black lung disease research, was incorporated into NIOSH, and its building in Morgantown, West Virginia was opened in 1971.[32] As of 1976,[update] NIOSH also continued to operate its Salt Lake City facility.[25]

Later history

[edit]

In 1981, the headquarters was moved from Rockville to Atlanta to co-locate with CDC headquarters.[23][33] The headquarters moved back to Washington, D.C. in 1994, though offices were maintained in Atlanta.[34]

When the U.S. Bureau of Mines was closed in 1996, its research activities were transferred to NIOSH along with two facilities in the Pittsburgh suburb of Bruceton, Pennsylvania, and in Spokane, Washington. The Pittsburgh campus dated from the beginning of the Bureau of Mines in 1910, and contained the historic Experimental Mine and Mine Roof Simulator, while the Spokane facility dated from 1951. NIOSH preserved the administrative independence of these activities by placing them in the new Office of Mine Safety and Health Research.[21]

In 1977, NIOSH had ten regional offices throughout the country.[35] These were closed over time, and by 1989 there were regional offices only in Denver and Boston.[36] The Alaska Field Station in Anchorage, Alaska was established in 1991 in response to the state having the highest work-related fatality rate, with Senator Ted Stevens playing a role in its establishment. It later become known as the Alaska Pacific Regional Office, and in 2015, the Denver, Anchorage, and non-mining Spokane staff joined into the Western States Division.[37][38]

In 1996, a large addition was built to the Morgantown facility containing safety engineering and bench laboratories.[32] In 2015, funding was approved for a new facility in Cincinnati to replace the Taft and Hamilton buildings, which were considered to be obsolete.[39] A location for the new facility in the Avondale neighborhood was announced in 2017,[40][41] and proposals from architectural and engineering firms were solicited in 2019.[42]

Directors

[edit]The following people were Director of NIOSH:[24]

- Marcus Key (1971–1975)

- John Finklea (1975–1978)

- Anthony Robbins (1978–1981)

- J. Donald Millar (1981–1993)

- Richard Lemen (Acting 1993–1994)

- Linda Rosenstock (1994–2000)

- Lawrence J. Fine (acting, 2000–2001)

- Kathleen Rest (acting, 2001–2002)

- John Howard (2002–2008; 2009–present)

- Christine Branche (acting, 2008–2009)

Other history

[edit]In 2001, NIOSH was called upon to help clean up Capitol Hill buildings after the 2001 anthrax attacks.[43]

See also

[edit]- Centers for Agricultural Safety and Health

- Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program

- Health Hazard Evaluation Program

- Immediately dangerous to life or health

- National Fire Fighter Near-Miss Reporting System

- NIOSH air filtration rating

- Occupational health psychology

- Prevention through design

- Occupational exposure banding

- Recommended exposure limit

- SENSOR-Pesticides

- Division of Industrial Hygiene

- N95 respirator

References

[edit]- ^ "NIOSH Divisions, Labs, and Offices". Archived from the original on October 20, 2009.

- ^ a b c About NIOSH. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- ^ "The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)". CDC. December 23, 2020.

- ^ "NIOSH Centers | NIOSH | CDC". CDC. 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

- ^ "PART 84—APPROVAL OF RESPIRATORY PROTECTIVE DEVICES".

- ^ "Counterfeit Respirators / Misrepresentation of NIOSH Approval". May 23, 2024.

- ^ National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (US) NIOSH Publications by Category

- ^ "National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Hearing Protector Device Compendium". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ^ "NIOSH Publications and Products – NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (2014-151)". CDC. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- ^ "NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards (NPG)". CDC. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ a b c NIOSH (December 1, 2011). "CDC - NIOSH - About NPPTL". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ^ a b c "NFPA and NIOSH form alliance for emergency responder safety". nfpa.org. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- ^ NIOSH (June 14, 2012). "CDC - Respirators - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- ^ "CDC - NIOSH - NIOSH-Approved Holiday, N95 Day". cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- ^ "CDC - NIOSH Program Portfolio : Personal Protective Technology : Program Description". cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-09-03.

- ^ "Certified Equipment List". CDC NIOSH. 25 August 2023.

- ^ NIOSH Education and Research Centers (ERCs). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. July, 2008. Accessed February 13, 2009

- ^ NIOSH ERC – Great Lakes Center. University of Illinois at Chicago. Accessed February 13, 2009

- ^ Education and Research Center (ERC): About ERC. University of Cincinnati, Department of Environmental Health. September 15, 2008. Accessed February 13, 2009

- ^ NIOSH Announces New Name for Centers to Reflect Education, Research Mission. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Update, January 22, 1998. Accessed February 13, 2009

- ^ a b Breslin, John A. (2010-02-01). "One Hundred Years of Federal Mining Safety and Health Research". U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. pp. 12, 32, 51, 55, 61–62. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ a b c The President's Report on Occupational Safety and Health. Commerce Clearing House. 1972. pp. 153–154.

- ^ a b c Etheridge, Elizabeth W. (1992-02-20). Sentinel for Health: A History of the Centers for Disease Control. University of California Press. pp. 230, 317. ISBN 978-0-520-91041-6.

- ^ a b c "Contributing Organizations – NIOSH". Safety and Health Historical Society (SHHS). 16 October 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ a b c "News from NIOSH". Job Safety & Health. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 1976. p. 37.

- ^ a b "Andrew W. Breidenbach Environmental Research Center". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 1990-04-01. p. 3. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ a b Rogers, Jerry R.; Symons, James M.; Sorg, Thomas J. (2013-05-28). "The History of Environmental Research in Cincinnati, Ohio: From the U.S. Public Health Service to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency". World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2013. American Society of Civil Engineers: 33–37. doi:10.1061/9780784412947.004. ISBN 978-0-7844-1294-7.

- ^ "Laboratory research, field investigation, and training program of the Robert A. Taft Sanitary Engineering Center at Cincinnati, Ohio". Public Health Reports. 69 (5): 507–512. 1954-05-01. ISSN 0094-6214. PMC 2024349. PMID 13167275.

- ^ Walsh, John (1964-07-03). "Environmental Health: Taft Center in Cincinnati Has Been the PHS Mainstay in Pollution Research". Science. 145 (3627): 31–33. Bibcode:1964Sci...145...31W. doi:10.1126/science.145.3627.31. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 14162688.

- ^ a b "Alice Hamilton Awards: History of Alice Hamilton, MD". U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Howard, John (2006-10-01). "NIOSH Cincinnati: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow". NIOSH eNews. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ a b Headley, Tanya; Shahan, Katie (2014-04-21). "The History and Future of NIOSH Morgantown". NIOSH Science Blog. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Sun, M (1981-10-09). "Reagan reforms create upheaval at NIOSH". Science. 214 (4517): 166–168. Bibcode:1981Sci...214..166S. doi:10.1126/science.7280688. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 7280688.

- ^ "New Directions at NIOSH". U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: 2. 1997. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB97100. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ A Management Guide to Carcinogens: Regulation and Control. U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 1977. p. 76.

- ^ Health and Safety in Small Industry. CRC Press. 1989-03-01. ISBN 978-0-87371-195-1.

- ^ Howard, John (2016-06-15). "Making Alaska a Safer Place to Work". NIOSH Science Blog. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ "In Memoriam: Ted Stevens". NIOSH eNews. 2010-09-01. Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- ^ Eaton, Emilie (2015-02-23). "$110 million allocated to build new NIOSH facility". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ^ Coolidge, Alexander (2017-07-13). "Avondale could land $110M federal building". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ^ "Draft Environmental Impact Statement: Site Acquisition and Campus Consolidation Cincinnati, Ohio". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. General Services Administration. 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ^ Holthaus, David (2019-09-10). "New tenants in the Uptown Innovation Corridor will include chemists, biologists, and engineers". Soapbox Cincinnati. Retrieved 2019-12-31.

- ^ "The Anthrax Cleanup of Capitol Hill." Documentary by Xin Wang produced by the EPA Alumni Association. Video, Transcript (see p. 3, 4, 5). May 12, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Roelofs, Cora (2007), Preventing Hazards at the Source, AIHA, pp. 23–31, ISBN 978-1-931504-83-6

- Zak Figura, Susannah (October 1995), "NIOSH under siege", Occupational Hazards, 57 (10), Penton Media: 161

External links

[edit]- Official website

- NIOSH account on USAspending.gov

- Global Environmental and Occupational Health e-Library online database of environmental health and occupational health and safety training materials