0-6-0

| |||||||||||||||||||

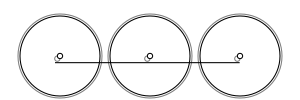

Hackworth's Royal George of 1827 | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

0-6-0 is the Whyte notation designation for steam locomotives with a wheel arrangement of no leading wheels, six powered and coupled driving wheels on three axles, and no trailing wheels. Historically, this was the most common wheel arrangement used on both tender and tank locomotives in versions with both inside and outside cylinders.

In the United Kingdom, the Whyte notation of wheel arrangement was also often used for the classification of electric and diesel-electric locomotives with side-rod coupled driving wheels. Under the UIC classification, popular in Europe, this wheel arrangement is written as C if the wheels are coupled with rods or gears, or Co if they are independently driven, the latter usually being electric and diesel-electric locomotives.[1]

Overview

[edit]History

[edit]The 0-6-0 configuration was the most widely used wheel arrangement for both tender and tank steam locomotives. The type was also widely used for diesel switchers (shunters). Because they lack leading and trailing wheels, locomotives of this type have all their weight pressing down on their driving wheels and consequently have a high tractive effort and factor of adhesion, making them comparatively strong engines for their size, weight and fuel consumption. On the other hand, the lack of unpowered leading wheels have the result that 0-6-0 locomotives are less stable at speed. They are therefore mostly used on trains where high speed is unnecessary.

Since 0-6-0 tender engines can pull fairly heavy trains, albeit slowly, the type was commonly used to pull short and medium distance freight trains such as pickup goods trains along both main and branch lines. The tank engine versions were widely used as switching (shunting) locomotives since the smaller 0-4-0 types were not large enough to be versatile in this job. 0-8-0 and larger switching locomotives, on the other hand, were too big to be economical or even usable on lightly built railways such as dockyards and goods yards, precisely the sorts of places where switching locomotives were most needed.

The earliest 0-6-0 locomotives had outside cylinders, as these were simpler to construct and maintain. However, once designers began to overcome the problem of the breakage of the crank axles, inside cylinder versions were found to be more stable. Thereafter this pattern was widely adopted, particularly in the United Kingdom, although outside cylinder versions were also widely used.

Tank engine versions of the type began to be built in quantity in the mid-1850s and had become very common by the mid-1860s.[2]

Early examples

[edit]0-6-0 locomotives were among the first types to be used. The earliest recorded example was the Royal George, built by Timothy Hackworth for the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1827.

Other early examples included the Vulcan, the first inside-cylinder type, built by Charles Tayleur and Company in 1835 for the Leicester and Swannington Railway, and Hector, a Long Boiler locomotive, built by Kitson and Company in 1845 for the York and North Midland Railway.[3]

Derwent, a two-tender locomotive built in 1845 by William and Alfred Kitching for the Stockton and Darlington Railway, is preserved at Darlington Railway Centre and Museum.

Suffixes

[edit]For a steam tank locomotive, the suffix usually indicates the type of tank or tanks:

- 0-6-0T – side tanks

- 0-6-0ST – saddle tank

- 0-6-0PT – pannier tanks

- 0-6-0WT – well tank

Other steam locomotive suffixes include

- 0-6-0VB – vertical boiler

- 0-6-0F – fireless locomotive

- 0-6-0G – geared steam locomotive

For a diesel locomotive, the suffix indicates the transmission type:

- 0-6-0DM – mechanical transmission

- 0-6-0DH – hydraulic transmission

- 0-6-0DE – electric transmission

Usage

[edit]All the major continental European railways used 0-6-0s of one sort or another, though usually not in the proportions used in the United Kingdom. As in the United States, European 0-6-0 locomotives were largely restricted to switching and station pilot duties, though they were also widely used on short branch lines to haul passenger and freight trains. On most branch lines, though, larger and more powerful tank engines tended to be favoured.

Australia

[edit]In New South Wales, the Z19 class was a tender type with this wheel arrangement. The Dorrigo Railway Museum collection includes seven Locomotives of the 0-6-0 wheel arrangement, including two Z19 class (1904 and 1923), three 0-6-0 saddle tanks and two 0-6-0 side tanks.

In Victoria, the Geelong and Melbourne Railway Company operated four 0-6-0WT (well tank) goods locomotives; one of their 2-2-2WT passenger locomotives ("Titania", which became Victorian Railways number 34 in 1860) was converted to an 0-6-0WT in 1872.[4]

On the Victorian Railways system there were O, P, Q, old R, Belgian R, new R, RY, T, U, Nos.103 & 105 (unclassed), old V, X, and Y class 0-6-0 tender locomotives, as well as a solitary Z class 0-6-0T (tank) engine.[4] Three types of 0-6-0 Diesel shunting locomotives were also used by the Victorian Railways, the F, M, and W classes.

Finland

[edit]

Tank locomotives used by Finland were the VR Class Vr1 and VR Class Vr4.

The VR Class Vr1s were numbered 530 to 544, 656 to 670 and 787 to 799. They had outside cylinders and were operational from 1913 to 1975. Built by Tampella, Finland and Hanomag (Hannoversche Maschinenbau AG), they were nicknamed Chicken. Number 669 is preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum.

The Vr4s were a class of only four locomotives, numbered 1400 to 1423, originally built as 0-6-0s by Vulcan Iron Works, United States, but modified to 0-6-2s in 1951–1955, and re-classified as Vr5.

Finland's tender locomotives were the classes C1, C2, C3, C4, C5 and C6.

The Finnish Steam Locomotive Class C1s were a class of ten locomotives numbered 21 to 30. They were operational from 1869 to 1926. They were built by Neilson and Company and were nicknamed Bristollari. Number 21, preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum, is the second oldest preserved locomotive in Finland.

The eighteen Class C2s were numbered 31 to 43 and 48 to 52. They were also nicknamed Bristollari.

The C3 was a class of only two locomotives, numbered 74 and 75.

The thirteen Class C4s were numbered 62 and 78 to 89.

The fourteen Finnish Steam Locomotive Class C5s were numbered 101 to 114. They were operational from 1881 to 1930. They were built by Hanomag in Hannover and were nicknamed Bliksti. No 110 is preserved at the Finnish Railway Museum.

The C6 was a solitary class of one locomotive, numbered 100.

Indonesia

[edit]Skirt tank locomotives

[edit]

The colonial government of the Dutch East Indies ordered Nederlandsch Indische Spoorweg Maatschappij (NIS) to build a 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) railway line connecting Yogyakarta to Magelang around 47 km (29 miles), which was the important city for the economic and defense sectors in Central Java and finished in 1898. By 1903–1907, they continued to build the line from Magelang to Secang–Ambarawa–Temanggung–Parakan because there were tobacco plantations. Just after the line finished, the NIS ordered around 12 units of 0-6-0T (skirt tank) locomotives from Sachsische Maschinenfabrik (Hartmann), Germany and came in 1899-1908 and they were classified as NIS Class 250 (NIS 250–262), these locomotives were used to haul mixed freight and passenger trains.[5] By 1914, NIS Class 251, 253, 255, 256, 257 were moved to Solo (Purwosari)–Boyolali (23 km / 14 miles) line and Solo–Wonogiri–Baturetno (51 km / 32 miles) line for sugarcane freight and passenger transports, both of the lines were purchased by NIS from the Solosche Tramweg Maatschappij (SoTM) or Solo Tramway Company. They also acquired a 0-6-0T which had been operated by SoTM with similar characteristic and performance also its manufacturer which then completed its skirt tanks collection to 13 units and renumbered as NIS Class 259. At first, these 0-6-0Ts were saturated steam and the tanks are located at both low sides of boiler near the wheels, they have a water capacity of 3 m3 and their length is 7,940 mm and they used inside cylinders. The driving wheels of the locomotive has a distinctive feature, using the 'Golsdorf' wheel movement systems. By this, all wheels (first wheel, second and third wheel) would only shift left/right following the rail track. Wheels with the 'Golsdorf' system are suitable for railroads with a large bend radius. This system was patented by Austrian railway engineer Karl Golsdorf. By 1924–1931, the NIS Class 250, 252, 254, 258 and 259 were converted and equipped with superheater technology and cylinder with piston valve. During Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies in 1942, all of Dutch East Indies private or state owned railway locomotives were renumbered based on Japanese numberings, while the NIS Class 250s were renumbered to C16, C17 and C18 and still used after Indonesian Independence by Djawatan Kereta Api (DKA) or Department of the Railways of Railways of the Republic of Indonesia until the era of Perusahaan Jawatan Kereta Api (PJKA) or Railway Bureau Company, out of 13 locomotives only C16 03, C17 04 and C18 01 are preserved in Ambarawa Railway Museum.[5][6]

Side tank locomotives

[edit]

Nederlandsch Indische Spoorweg Maatschappij (NIS) was known operating its 4 ft 8½ in (1,435 mm) gauge between Samarang–Vorstenlanden (Solo and Yogyakarta), Brumbung–Gundih and Kedungjati–Ambarawa all of which had been built in the 1870s. NIS expanded its rail network in Jogja (another term of Yogyakarta) by building branch lines between Yogyakarta–Brosot–Sewugalur in 1895 and Yogyakarta–Pundong in 1919. The line construction in and around Jogja was also to serve the freight transports of sugarcane from many sugar mills that operating in the royal land of Yogyakarta Sultanate. NIS imported another 10 new 0-6-0Ts as standard-gauge runner on Samarang–Vorstenlanden and came in 2 batches in 1910 and 1912 from Werkspoor, N.V., Netherlands.[7] The first batch engines were classified as NIS 151–156, those on second batch were NIS 157–160 and equipped with steam brake.[5] These locomotives often worked on southern lines of Jogja. Since Japanese occupation in 1942, the entire of NIS standard-gauge lines were converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge which made almost NIS standard gauge locomotives were found derelict. All of NIS 151–160 were also scrapped after Indonesian Independence, while the last one of them was found derelict in Pengok Workshop, Yogyakarta in 1974.[8]

In 1901, the Staatsspoorwegen (SS) acquired 24 units of 0-6-0Ts from Solo Vallei Waterwerken or Solo Valley Waterworks after they sold it due to debts as a result of swelling funds for the construction of irrigation canal dams on the banks of the Bengawan Solo and then, SS classified them as SS Class 500 (501–524). Not quite a long, a local private tramway company named Pasoeroean Stoomtram Maatschappij (PsSM) bought 2 units from SS to assist their sugar-freight transports to the port there along with their Hohenzollern 0-4-0Tr engines in 1905 and 1908. The remaining owned by the SS were renumbered as SS Class 24–45 and used to aid mainline and rural tramlines, especially in East Java between Garahan–Banyuwangi line using as transport for construction materials and metal bridge girders. After that, they were used as yard shunter and short harbor works at Banyuwangi and Panarukan. While 2 units of Solo Vallei which were acquired by PsSM renumbered to PsSM 6 Louisa (former SS 506) and PsSM 7 Marie (former SS 516), by 1911 they also purchased brand new of the same type PsSM 8 Nella. These locomotives were manufactured by John Cockerill & Cie., Belgium. After Japanese occupation, the SS Class 24–45 were renumbered as C13 class and PsSM 6–8 were reclassified as C22 class, the C13s were brought by Japanese throughout Java while the C22s were brought to Mojokerto as yard shunt duties. From all of these locomotives, not a single one remains. All of them were scrapped around the 1970s.[5][9][10]

In addition to operating trams for transportation facilities in the city of Semarang, Central Java, the private tramway company of Semarang-Joana or Semarang-Joana Stoomtram Maatschappij (SJS) was also extending the construction of their 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) lines to the east, which connected to Rembang, Blora and Cepu. The line of Semarang–Demak–Kudus–Rembang (197 km / 122 miles) was built in 1883–1900, while the Rembang–Blora–Cepu line (70 km / 43 miles) was completed in 1902. The line to Cepu was used for oil transportation and by this area there are fairly extensive teak forests. To serve the freight or passenger transportation on those lines, the SJS ordered 12 '0-6-0T' locomotives from Sächsische Maschinenfabrik (Hartmann) and came in 1898–1902 and classified as SJS Class 100 (101–112). Originally these locomotives had a funnel-shaped chimney, but was later replaced by a straight one and also equipped with a sand box which it made of brass. During Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies, all of SJS Class 100s were renumbered to C19 and still used up today. After World War II ended, 2 units of C19 locomotives were moved from Java to West Sumatra at the Padang locomotive depot to meet the needs of rail transportation in West Sumatra. At the end of its service period around 1973, the C19 locomotive was used to haul the molasses tank wagons around Probolinggo–Pajarakan.[5][6] From 12 of them, only C19 12 or SJS 112 is preserved at the Transportation Museum of Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Jakarta.

In 1895–1896, two private-owned tramway company named Modjokerto Stoomtram Mij. (Mdj.SM) and Babat Djombang Stoomtram Mij. (BDSM) received the permit concession from the colonial Dutch government to build the line of Porong–Gunung Gangsir–Bangil–Pandaan–Japanan–Mojokerto and Sidoarjo–Tarik–Mojokerto–Jombang which were connected to Staatsspoorwegen (SS) lines. In addition, the BDSM was also built their line of Babat–Jombang to serve sugarcane freight transports which was connected to Nederlandsch-Indische Spoorweg Mij. (NIS) line at the Soerabaia NIS (Surabaya Pasar Turi), Babat and Cepu railway stations. The Mdj. SM completed their line construction in 1899, while BDSM completed in 1902 and 1913. To serve their rail transports, The Mdj. SM imported 4 locomotives in 1907–1926 (classified as MSM 11, 12, 15 and 16) and BDSM imported 2 of them in 1903 and 1903 (classified as BDSM 9 &10) from Georg Krauß, Germany. BDSM was defunct in 1916 due to the company's financial difficulties, so all of its assets including their two 0-6-0T units were acquired by SS (became SS 113 &114). After Japanese occupation, they were classified as C21 class.[5][6] From 6 of them only 2 remained, the C21 02 of BDSM in INKA, Madiun and C21 03 of Mdj. SM in Taman Mini Indonesia Indah.

Well Tank locomotives

[edit]

Type C2-Lts later classified as NIS 106 and NIS 107 were the first generation of 0-6-0WT operated by NIS from Hanomag, Germany and came in 1901. These C2-Lts were wood and coal burners and had a maximum speed of 40 kilometres per hour (24.8 miles per hour).[5] These locomotives often worked on southern lines of Jogja. Since Japanese occupation in 1942, the entire of NIS standard-gauge lines were converted to 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) gauge which made almost NIS standard gauge locomotives were found derelict. Just before occupation, NIS 106 and 107 were converted became armored locomotive by J. C. Jonker who was the former head of NIS traction depot. The last known NIS 106 was re-gauged to 1,067 mm and operating as short harbor works in Semarang in July 1945 before being scrapped by Japanese. The chassis of NIS 107 still be found in front of SMK Negeri 2 Yogyakarta (state vocational school), while the most parts of it had been stripped down by the Japanese.[8]

New Zealand

[edit]In New Zealand the 0-6-0 design was restricted to tank engines. The Hunslet-built M class of 1874 and Y class of 1923 provided 7 examples, however the F class built between 1872 and 1888 was the most prolific, surviving the entire era of NZR steam operations, with 88 examples of which 8 were preserved.

Philippines

[edit]

This wheel arrangement was first introduced in 1905. Most of the preserved steam locomotives in the country are of this type as they were popular among sugarcane plantation, sawmill and coal mine owners.

Tank and tank-tender locomotives

[edit]The first operators of the type were the Manila Railway with its 0-6-0T Cabanatuan class, named after the now-defunct branch line towards Cabanatuan. Two of these locomotives were built, No. 777 Cabanatuan and No. 778 Batangas. It was followed by the 0-6-2ST Cavite class of 1906, after also defunct Naic branch of the PNR South Main Line. This was later known as the V class. No. 777 Cabanatuan and No. 1007 Dagupan (originally Cavite) are in display in front of the Philippine National Railways headquarters at Tutuban station in Tondo, Manila.

This type was also used by the 3 ft gauge railways in Negros Island. Central Azucarera de Bais operated 3 tank locomotives. The De La Rama conglomerate of Bago, Negros Occidental led by Esteban de la Rama (1866–1947) had Locomotive No. 2.[11] Other operators include Ma-Ao Sugar Central,[12] the National Coal Company in which used this locomotive as a 0-6-0STT tank tender,[13] and San Carlos Milling Company No. 4 of 1919.[14]

Tender locomotives

[edit]The Hawaiian-Philippine Company of Silay, Negros Occidental operates three 0-6-0 tender locomotives and are the last active steam locomotives in the country. The three locomotives are No. 2 Peter Francis Davies of 1919, No. 5 The Isabella Curran of 1920 and No. 7 Edwin H. Herkes of 1928.[15] These are still used for its heritage railway service after the rail freight service was terminated in 2021. No. 7 was later renamed as the second Isabella Curran.[16] Aside from these, the company also had two more locomotives of the same arrangement that were most likely scrapped.[17]

Other known operators of tender locomotives include Central Azucarera de Bais with its Baldwin-built also numbered No. 7,[18] North Negros Sugar Company,[19] San Carlos No. 5 of 1926,[14] and Tabacalera Central No. 5 of 1927.[20] Out of these, only the Tabacalera Central No. 5 uses the 3 ft 6 in gauge lines being operated in Tarlac while the other units use the 3 ft gauge.

South Africa

[edit]Cape gauge

[edit]In 1876, the Cape Government Railways (CGR) placed a pair of 0-6-0 Stephenson's Patent permanently coupled back-to-back tank locomotives in service on the Cape Eastern system. They worked out of East London in comparative trials with the experimental 0-6-0+0-6-0 Fairlie locomotive that was acquired in that same year.[21][22][23]

The Natal Harbours Department placed a single 0-6-0 saddle-tank locomotive in service in 1879, named John Milne.[24][25]

The Natal Government Railways placed a single locomotive in shunting service in 1880, later designated Class K, virtually identical to the Durban Harbour's John Milne and built by the same manufacturer.[24][25]

In 1882, two 0-6-0 tank locomotives entered service on the private Kowie Railway between Grahamstown and Port Alfred. Both locomotives were rebuilt to a 4-4-0T wheel arrangement in 1884.[21]

In 1890, the Nederlandsche-Zuid-Afrikaansche Spoorweg-Maatschappij of the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (Transvaal Republic) placed six 18 Tonner 0-6-0ST locomotives in service on construction work.[21]

In 1896 and 1897, three 26 Tonner saddle-tank locomotives were built for the Pretoria-Pietersburg Railway (PPR) by Hawthorn, Leslie and Company. These were the first locomotives to be obtained by the then recently established PPR. Two of these, named Nylstroom and Pietersburg, came into SAR stock in 1912 and survived into the 1940s.[21][25][26]

In 1901, a single 0-6-0T harbour locomotive built by Hudswell, Clarke was delivered to the Harbours Department of Natal. It was named Edward Innes and retained this name when it was taken onto the SAR roster in 1912.[24][25][26]

Two saddle-tank locomotives were supplied to the East London Harbour Board in 1902, built by Hunslet. Both survived until the 1930s, well into the SAR era.[24][25]

In 1904, a single saddle tank harbour locomotive, named Sir Albert, was built by Hunslet for the Harbours Department of Natal. It came into SAR stock in 1912 and was withdrawn in 1915.[24][25][26]

Narrow gauges

[edit]In 1871, two 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauge tank locomotives, built by the Lilleshall Company of Oakengates, Shropshire in 1870 and 1871, were placed in service by the Cape of Good Hope Copper Mining Company. Named John King and Miner, they were the first steam locomotives to enter service on the hitherto mule-powered Namaqualand Railway between Port Nolloth and the Namaqualand copper mines around O'okiep in the Cape Colony.[27]

In 1902, Arthur Koppel, acting as agent, imported a single 0-6-0 2 ft (610 mm) narrow gauge tank steam locomotive for a customer in Durban. It was then purchased by the Cape Government Railways and used as construction locomotive on the Avontuur branch from 1903. In 1912, this locomotive was assimilated into the South African Railways and in 1917 it was sent to German South West Africa during the First World War campaign in that territory.[22][25]

South West Africa

[edit]

Between 1898 and 1905, more than fifty pairs of Zwillinge twin tank steam locomotives were acquired by the Swakopmund-Windhuk Staatsbahn (Swakopmund-Windhoek State Railway) in Deutsch-Südwest-Afrika (DSWA, now Namibia). Zwillinge locomotives were a class of small 600 mm (1 ft 11+5⁄8 in) Schmalspur (narrow gauge) 0-6-0T tank steam locomotives that were built in Germany in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As indicated by their name Zwillinge (twins), they were designed to be used in pairs, semi-permanently coupled back-to-back at the cabs, allowing a single footplate crew to fire and control both locomotives. The pairs of locomotives shared a common manufacturer's works number and engine number, with the units being designated as A and B. By 1922, when the SAR took control of all railway operations in South West Africa (SWA), only two single Illinge locomotives survived to be absorbed onto the roster of the SAR.[25]

In 1907, the German Administration in DSWA acquired three Class Hc tank locomotives for the narrow gauge Otavi Mining and Railway Company. One more entered service in 1910, and another was obtained by the South African Railways in 1929.[25]

In 1911, the Lüderitzbucht Eisenbahn (Lüderitzbucht Railway) placed two Cape gauge 0-6-0T locomotives in service as shunting engines. They were apparently no longer in service when all railways in the territory came under the administration of the South African Railways in 1922.[28]

Switzerland

[edit]During the Second World War, Switzerland converted some 0-6-0 shunting engines into electric–steam locomotives.

United Kingdom

[edit]The 0-6-0 inside-cylinder tender locomotive type was extremely common in Britain for more than a century and was still being built in large numbers during the 1940s. Between 1858 and 1872, 943 examples of the John Ramsbottom DX goods class were built by the London and North Western Railway and the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. This was the earliest example of standardisation and mass production of locomotives.[29]

Of the total stock of standard-gauge locomotives operating on British railways in 1900, around 20,000 engines, over a third were 0-6-0 tender types. The ultimate British 0-6-0 was the Q1 Austerity type, developed by the Southern Railway during the Second World War to haul very heavy freight trains. It was the most powerful steam 0-6-0 design produced in Europe.

Similarly, the 0-6-0 tank locomotives became the most common locomotive type on all railways throughout the 20th century. All of the Big Four companies to emerge from the Railways Act, 1921 grouping used them in vast numbers. The Great Western Railway, in particular, had many of the type, most characteristically in the form of the pannier tank locomotive that remained in production well past railway nationalisation in 1948.

When diesel shunters began to be introduced, the 0-6-0 type became the most common. Many of the British Railways shunter types were 0-6-0s, including Class 03, the standard light shunter, and Class 08 and Class 09, the standard heavier shunters.

United States

[edit]In the United States, huge numbers of 0-6-0 locomotives were produced, with the majority of them being used as switchers. The USRA 0-6-0 was the smallest of the USRA Standard classes designed and produced during the brief government control of the railroads through the USRA during the First World War. 255 of them were built and ended up in the hands of about two dozen United States railroads.

In addition, many of the railroads (and others) built numerous copies after the war. The Pennsylvania Railroad rostered over 1,200 0-6-0 types over the years, which were classed as class B on that system. The United States 0-6-0s were generally tender locomotives.

During the Second World War, no fewer than 514 USATC S100 Class 0-6-0 tank engines were built by the Davenport Locomotive Works, for use by the United States Army Transportation Corps in both Europe and North Africa. Some of these remained in service long after the war, having been purchased or otherwise adopted by the countries where they were used. These included Austria, Egypt, France, Iraq, the United Kingdom and Yugoslavia.

The fourteen SR USA Class engines purchased by the British Southern Railway in 1946 remained in service well into the 1960s. Designed to be extremely strong but easy to maintain, these engines had a very short wheelbase that allowed them to operate on dockyard railways.

References

[edit]- ^ Whyte notation

- ^ Bertram Baxter, British locomotive catalogue 1825–1923, Vol.1, Moorland Publishing, 1977.

- ^ The Science Museum, The British railway locomotive 1803-1850, H.M.S.O., 1958.

- ^ a b Cave, Norman; Buckland, John; Beardsell, David (2002). Steam Locomotives of the Victorian Railways. Volume 1: The First Fifty Years. Melbourne: Australian Railway Historical Society (Victorian Division). ISBN 1-876677-38-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Oegema, J. J. G. (1982). De Stoomtractie op Java en Sumatra (in Dutch). Deventer-Antwerpen: Kluwer Technische Boeken, B.V. ISBN 978-90-201-1520-8.

- ^ a b c Yoga Bagus Prayogo; Yohanes Sapto Prabowo; Diaz Radityo (2017). Kereta Api di Indonesia. Sejarah Lokomotif di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Jogja Bangkit Publisher. ISBN 978-602-0818-55-9.

- ^ De Jong, H. (1986). De Locomotieven van Werkspoor (in Dutch). Alk. ISBN 978-90-6013-933-2.

- ^ a b Dickinson, Rob. "Steam in Java". The International Steam Pages.

- ^ de Bruin, Jan (2003). Het Indische Spoor in Oorlogstijd (in Dutch). Uquilair. ISBN 978-90-71513-46-6.

- ^ Cholisi, A. B. "Class C13/C22 Steam Locomotive". Tracing The Lost Railway Lines of Indonesia. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

- ^ Wright, Roy (1922). 1922 Locomotive Cyclopedia of American Practice. Simmons-Boardman Publishing., as cited by Llanso, Steve. "Esteban de la Rama 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "Ma-Ao Sugar Central 0-6-0 Locomotives in Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "National Coal Company 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ a b Llanso, Steve. "San Carlos Milling Company 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Barnes, Eddie (2016-12-14). "Extant Steam in the Philippines, December 2016". International Steam. Retrieved 2022-04-01.

- ^ Poblacion, Lloyd Gerald (2020-09-26). The Hawaiian-Philippine Sugar Company. Philippine Rail Enthusiasts and Railfans Club. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "Hawaiian-Philippine 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "Central Azucarera de Bais 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "North Negros Sugar Company 0-6-0 Locomotives in [the] Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ Llanso, Steve. "Tabacalera Central/CA de Bais 0-6-0 Locomotives in Philippines". SteamLocomotive.com. Sweat House Media. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- ^ a b c d Holland, D.F. (1971). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. Vol. 1: 1859–1910 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, England: David & Charles. pp. 25–28, 80–83, 110, 118. ISBN 978-0-7153-5382-0.

- ^ a b Dulez, Jean A. (2012). Railways of Southern Africa 150 Years (Commemorating One Hundred and Fifty Years of Railways on the Sub-Continent – Complete Motive Power Classifications and Famous Trains – 1860–2011) (1st ed.). Garden View, Johannesburg, South Africa: Vidrail Productions. pp. 21–22, 232. ISBN 9 780620 512282.

- ^ What were these, 2-6-0T or 0-6-0T?

- ^ a b c d e Holland, D. F. (1972). Steam Locomotives of the South African Railways. Vol. 2: 1910-1955 (1st ed.). Newton Abbott, England: David & Charles. pp. 120, 125–129, 131. ISBN 978-0-7153-5427-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Paxton, Leith; Bourne, David (1985). Locomotives of the South African Railways (1st ed.). Cape Town: Struik. pp. 21–24, 26, 111–112, 116–117, 121, 157. ISBN 0869772112.

- ^ a b c Classification of S.A.R. Engines with Renumbering Lists, issued by the Chief Mechanical Engineer's Office, Pretoria, January 1912, pp. 2, 11, 13 (Reprinted in April 1987 by SATS Museum, R.3125-6/9/11-1000)

- ^ Bagshawe, Peter (2012). Locomotives of the Namaqualand Railway and Copper Mines (1st ed.). Stenvalls. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-91-7266-179-0.

- ^ Espitalier, T.J.; Day, W.A.J. (1948). The Locomotive in South Africa - A Brief History of Railway Development. Chapter VII - South African Railways (Continued). South African Railways and Harbours Magazine, January 1948. p. 31.

- ^ H.C. Casserley, The historic locomotive pocket book, Batsford, 1960, p.23.

External links

[edit]- Building a 1/8 scale Live Steam 0-6-0 locomotive This site includes a full 1914 factory drawing of a Finnish 0-6-0 switcher.