Flag of Senegal

| |

| Use | National flag and ensign |

|---|---|

| Proportion | 2:3 |

| Adopted | 20 August 1960 |

| Design | A vertical tricolour of green, yellow and red; charged with a green five-pointed star at the centre. |

The national flag of Senegal (drapeau national du Sénégal) is a tricolour consisting of three vertical green, yellow and red bands charged with a five-pointed green star at the centre.[1] Adopted in 1960 to replace the flag of the Mali Federation, it has been the flag of the Republic of Senegal since the country gained independence that year. The present and previous flags were inspired by the French tricolour, which flew over Senegal until 1960.

History

[edit]

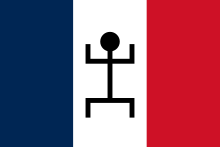

Under French colonial rule over Senegal, the authorities forbade the colony from using its own distinctive colonial flag because they were worried that this could increase nationalistic sentiment and lead to calls for independence.[2] With the rise of the decolonization movement in Africa, the French were obliged to grant limited autonomy to Senegal as a self-governing republic within the French Community. Senegal was combined with French Sudan on April 4, 1959, to form the Mali Federation.[3] That day, a new flag was adopted: a vertical green, yellow and red tricolour with a stylized depiction of a human being (referred to as a kanaga) on the centre band.[4][5] The federation attained independence from France on June 20, 1960.[3]

The federation between the two former colonies did not last long and ended two months after independence.[4][6] On August 20, Senegal separated from the federation and became an independent country.[5] The new nation's flag kept the colours and stripes of the federation's flag, with the only change being the replacement of the kanaga with a green star.[7]

In April 2004, the flag and its design were hoist into the public colloquium when Moustapha Niasse, then-leader of the Alliance of the Forces of Progress, hosted a press conference regarding the "modification of the election code and the set up of an independent commission to check the lawfulness of the next legislative and presidential elections."

At the conference's coda, Niasse explored what he felt was "defense of the symbols of the Republic against the division threat and the offence against national unity", and produced "[a] visible replacement, on certain official documents, of the green star of the central yellow stripe of the national flag by a golden baobab", alongside what he described as "the non-performance of the national anthem during official ceremonies".[8][9]

The newspaper WalFadjri reported on the same press conference with an emphasis on the alleged transmutation of the national symbology, even going so far as to entitle the feature "President Wade creates a new flag". Niasse again produced what he flaunted as an "official document signed by the head of state...with a golden baobab instead of the green star." Niasse himself stated "Only the Senegalese people is sovereign to decide any modification of the symbols of our Republic".[9]

Design

[edit]Symbolism

[edit]Much symbolism and many connotations are beholden to the stripes and singular star of the Senegalese flag. From a national perspective, green is highly symbolic within all of the country's primary religions. In Islam, the country's majority religion at 94% percent of the population,[10] the green of both the first stripe and the star represent the colour of the Prophet,[11][12] Christians see the presence of green as a portent of hope, and Animists (or adherers to Traditional African religions) view green as representative of fecundity.[5]

The Senegalese government offers exegesis for the presence of yellow and red as well, yellow being "the symbol of wealth; it represents the product of work, for a nation whose main priority is the progress of economy, which will allow the increase of the cultural level, the second national priority." Additionally, yellow is denoted as "the colour of arts, literature, and intellect", primarily because literature teachers in Senegal are known to wear yellow blouses. Red "recalls the colour of blood, therefore colour of life and the sacrifice accepted by the nation, and also of the strong determination to fight against underdevelopment."[5][9][13]

Historically, the three colours represent the three political parties which merged to form Union Progressiste Sénégalaisé (Senegalese Progressist Union, now Socialist Party of Senegal, Leopold Senghor's party): green for Bloc Démocratique Sénégalais (Senegalese Democratic Bloc), yellow for Mouvement Populaire Sénégalais (Senegalese Popular Movement) and red for Parti Sénégalais d'Action Sociale (Senegalese Party of Socialist Action).[9]

Green, yellow and red are the colours of the Pan-Africanist movement.[7] That pattern was replicated on Senegal's flag as a sign of unity among African countries.[12] The quinary points of the star are said to either "recall the human ideogram which was displayed in the middle of the flag of the former Mali Federation"[9] or an adoption of the Serer cosmogonical and religious star Yooniir ― the symbol of the universe in Serer spirituality and cosmogony,[14][15] which also symbolises "good fortune and destiny" in the Serer worldview.[14] The symbol is represented by a black 5 pointed star which also spiritually and/or metaphorically denotes "the Black man standing head held high, hands raised representing work and prayer. Sign of God: Image of Man."[16] The first President of Senegal―Léopold Sédar Senghor who was of Serer origin, a founding-member of the Négritude Movement, and who had a history of appropriating (others say "celebrating") Serer religious symbols, mythology, and spiritual references in his works despite being a Catholic,[17] probably adopted the Serer religious star just like he did in 1978 when he bought the country's presidential plane and named it "Point de Sangomar" in reference to the Serer sacred site the Point of Sangomar - which in Serer means "the village of shadows".[18][19]

Historical flags

[edit]| Flag | Duration | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1958–1959 | Flag of French Senegal | A green field charged with a yellow star at the centre. |

|

1959–1960 | Flag of the Mali Federation within the French Community | A vertical tricolour of green, yellow and red charged with a stylized depiction of a human being (referred to as a kanaga) on the centre band |

Similar colours

[edit]The Pan-African colours of Senegal's flag are shared by several other countries in the region, including Cameroon, Guinea and Mali.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Flag Similarity Tends to Confuse". The Spokesman-Review. March 4, 1962. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Whitney. "Gabon, flag of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Mali Federation (African history)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ a b Kindersley, Dorling (November 3, 2008). Complete Flags of the World. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 9781405333023. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Whitney. "Senegal, flag of". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved May 24, 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ "History of Senegal". Lonely Planet. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Shaw, Carol P. (2004). Flags. HarperCollins UK. p. 203. ISBN 9780007165261. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ http://fr.allafrica.com/stories/200404160128.html Niasse Press Conference

- ^ a b c d e http://flagspot.net/flags/sn.html#mean Flagspot-Senegalese Flag

- ^ "The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity". The Pew Forum: On Religion and Public Life. 9 August 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Philip, George and Son (December 26, 2002). Encyclopedic World Atlas. Oxford University Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-0-19-521920-3. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ a b The Report: Senegal 2009. Oxford Business Group. 2009. p. 10. ISBN 9781902339214. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ Streissguth, Thomas (2009). Senegal in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. pp. 69. ISBN 9781575059518. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- ^ a b Madiya, Clémentine Faïk-Nzuji, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Canadian Centre for Folk Culture Studies, "International Centre for African Language, Literature and Tradition", (Louvain, Belgium), pp. 27, 155, ISBN 0-660-15965-1

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, La civilisation sereer, vol. II : "Pangool", Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1990, p 20, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, La civilisation sereer, vol. II : "Pangool", Nouvelles éditions africaines, Dakar, 1990, p 21, ISBN 2-7236-1055-1

- ^ Harney, Elizabeth, "In Senghor's Shadow: Art, Politics, and the Avant-Garde in Senegal, 1960–1995", Duke University Press (2004), p. 278, ISBN 9780822333951 [1] (retrieved 25 August 2023)

- ^ Jeune Afrique, "Avions présidentiels – Sénégal : Abdoulaye, Karim et Viviane sont dans un avion…" (3 July 2014). By Mehdi Ba [2] (retrieved 25 August 2023).

- ^ Gravrand, Henry, "Visage africain de l'Église", Orante, Paris, 1961, p. 285